The Birmingham Journal of Literature and Language (Print)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adventures in the Great Deserts;

■r Vi.. ^ ^ T. *''''”"^ ^ \ "VO'' ^ '' c ® ^ 4- ^O 0)*>‘ V ^ ‘ m/r/7-Ay * A ^ = i:, o\ , k'" o »• V Vt. ^ V. V ., V' -V ^ .0‘ ?- -P .Vi / - \'^ ?- - '^0> \'^ ■%/ *4 ^ %■ - -rVv ■'% '. ^ \ YT-^ ^ ® i. 'V, ^ .0^ ^o '' V^v O,^’ ^ ff \ ^ . -'f^ ^ 9 \ ^ \V ^ 0 , \> S ^ C. ^ ^ \ C> -4 y ^ 0 , ,V 'V '' ' 0 V c ° ^ '■V '^O ^ 4T' r >> r-VT^.^r-C'^>C\ lV«.W .#. : O .vO ✓< ^ilv ^r y ^ s 0 / '^- A ^■<-0, "c- \'\'iii'"// ,v .'X*' '■ - e.^'S » '.. ■^- ,v. » -aK®^ ' * •>V c* ^ "5^ .%C!LA- V.# - 5^ . V **o ' „. ,..j "VT''V ,,.. ^ V' c 0 ~ ‘, V o 0^ .0 O... ' /'% ‘ , — o' 0«-'‘ '' V / :MK^ \ . .* 'V % i / V. ' ' *. ♦ V' “'• c 0 , V^''/ . '■■.■- > oKJiii ^:> <» v^_ .^1 ^ c^^vAii^iv ^ Ji^t{f//P^ ^ •5.A ' V ^ ^ O 0 1J> iS K 0 ’ . °t. » • I ' \V ^9' <?- ° /• C^ V’ s ^ o 1'^ 0 , . ^ X . s, ^ ' ^0' ^ 0 , V. ■* -\ ^ * .4> <• V. ' « « (\\ 0 v*^ aV '<-> 'K^ A' A' ° / >. ''oo 7 xO^w. •/' «^UVvVNS" ■’» ^ ' «<• 0 M 0 ■ '*' 8 1 * // ^ . Sf ^ t O '^<<' A'- ' ♦ aVa*' . A\W/A o ° ^/> -' ■,y/- -i. _' ,^;x^l-R^ •y' P o %'/ A -oo' / r'-: -r-^ " . *" ^ / ^ '*=-.0 >'^0^ % ‘' *.7, >•'\«'^’ ,o> »'*",/■%. V\x-”x^ </> .^> [/h A- ^'y>. , ^ S?.'^ * '■'* ■ 1*' " -i ' » o A ^ ^ s '' ' ■* 0 ^ k'^ a c 0 ^ o' ' ® « .A .. 0 ‘ ='yy^^: -^oo' -"ass . - y/i;^ ~ 4 ° ^ > - A % vL" <>* y <* ^ 8 1 A " \^'' s ^ A ^ ^ ^ ^ o’ V- ^ <t ^ ^ y ^ A^ ^ n r* ^ Yj ^ =■ '^-y * / '% ' y V " V •/„■ /1 z ^ ’ ^ C y>- y '5>, ® Vy '%'■ V> - ^ ^ ^ C o' i I » I • I ADVENTURES IN THE GREAT DESERTS r* ADVENTURES IN THE GREAT DESERTS ROMANTIC INCIDENTS ^ PERILS OF TRAVEL, SPORT AND EXPLORATION THROUGHOUT THE WORLD BY H. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Thomas Witlam Atkinson (Bap. 1799–1861) – on the Edge 29

Thomas Witlam Atkinson 27 (bap. 1799–1861) – On the Edge “mr atkinson i presume?” In 1858 Thomas W. Atkinson shared the platform with Dr David Livingstone at a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society, Burlington House, London. The report of the meeting in the Illustrated London News of 16th January is headed: ‘The Travellers Livingstone and Atkinson’. By 1858 Livingstone had crossed Africa and Thomas had travelled 39,000 miles across Central Asia to territory no European had set foot on. Both had named their children after rivers in the countries they had explored. Both travelled with their wives. Now Thomas is the forgotten man, with a tarnished reputation. How much does luck, strength of character and influence ultimately decide lasting fame? Baptised in March 1799 at Cawthorne, Barnsley, Thomas Atkinson was the son of William, a stone mason at Cannon Hall, Cawthorne, home of the Spencer Stanhope family, and Martha Whitlam, a housemaid at Cannon Hall. Martha was William’s second wife and they had married on 19th August 1798 in Cawthorne. There were two more children of the marriage: Ellen, born 1801, and Ann, born 1804. When William died in 1827, he left the tenancy in the house he lived in to his daughter Ellen and the residue of his estate to the two girls. The house was on a 42-year lease from the late John Beatson of Cinder Hill Farm Cawthorne, commencing December 1822. Thomas is not mentioned in the will. Worthies of Barnsley records that Thomas was born in a house next to the Old Wesleyan chapel and went to school in Cawthorne. -

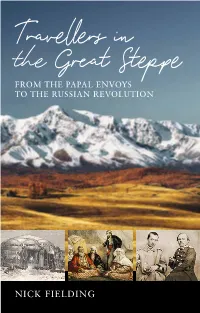

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Thomas Witlam Atkinson (1799-1861): a Brief Biography

Thomas Witlam Atkinson (1799-1861): A Brief Biography Barnsley is home to one of the great explorers Britain ever produced. It is time for his reputation to be restored to its rightful pace. He is the great unknown explorer. Nick Fielding (Journalist and Author) Thomas Witlam Atkinson was born in Cawthorne in 1799. His father was a stone-mason who worked at Cannon Hall and his mother was a house-maid there. Thomas trained as a stone-mason and then became an architect, working mainly on churches in and around Manchester and London. He married for the first time in Halifax in 1819. After Hamburg Cathedral was destroyed by a fire, a competition to rebuild it was held. Thomas travelled to Hamburg to enter the competition and there seems to have met people who suggested he travel to Russia. Thomas set out on his travels in 1847. According to his book, the sole purpose of his journey was to sketch. He was granted a personal passport by Tsar Nicholas I to enable him to travel in safety. Despite already being married, Thomas married for a second time in 1847. His second wife, Lucy (originally from Sunderland) had been working as a governess in Moscow. She accompanied Thomas on his travels and, in 1848, gave birth to a son named Alatau. Thomas and his new family travelled in central Asia until late 1853. It is thought that, in total, they travelled 39,000 miles by carriage, by boat and on horseback. Within a few years of the completing this journey, Thomas returned to England with Lucy and Alatau. -

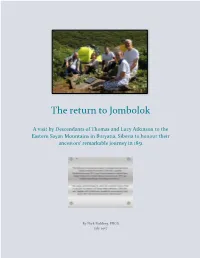

The Return to Jombolok

The return to Jombolok A visit by Descendants of Thomas and Lucy Atkinson to the Eastern Sayan Mountains in Buryatia, Siberia to honour their ancestors’ remarkable journey in 1851 By Nick Fielding, FRGS July 2017 The Return to Jombolok 1851-2017 Khi-Gol, the Jombolok Volcano Field (Photographs used in this report were taken by David O’Neill, Nick Fielding and Sasha Zhilinsky, unless otherwise indicated) PAGE | 1 The Return to Jombolok 1851-2017 1. Introduction For several years past I have been attempting to trace the remarkable series of journeys made by Thomas and Lucy Atkinson throughout Central Asia and Siberia in the course of the seven years from 1847-53. I have already visited the Zhetysu region of Eastern Kazakhstan on four occasions and in 2016 took a group of 10 descendants of the Atkinsons to that region to visit places associated with the couple and with the birth of their son, Alatau Tamchiboulac Atkinson, in November 1848. Some of the Atkinsons’ most important journeys took place in Eastern Siberia, as they spent two winters in the city of Irkutsk, close to Lake Baikal, and used this as a base from which to explore the region. In the winters, they would stay in town, where Thomas would convert his sketches into the wonderful watercolour paintings that have become his trademark, but as soon as the snow began to melt in the late spring, they would be off on horseback into the Siberian wilderness. This is precisely what happened on 23rd May 1851, when the Atkinsons set off from Irkutsk on an extended summer expedition to the Eastern Sayan Mountains in what is now western Buryatia, close to the border with the Republic of Tuva. -

Kazconf Speech

HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL LINKS OF GREAT BRITAIN AND KAZAKHSTAN A paper delivered to the Forum of Kazakhstan Culture and Literature By Nick Fielding London, 7th November 2017 In 10 minutes I cannot say a lot about the historical and cultural links of Great Britain and Kazakhstan. But they stretch back further than many of you may think. The first person from these islands to observe the Kazakhs and to comment on their society was John Castle. Castle was sent as a Russian envoy to what is now north-western Kazakhstan, to the court of Khan Abulkhayir, the leader of the Junior Juz at that time. Cover of John Castle's Journal and one of the plates Castle was working on behalf of the Russian Tsar and attempting to gauge the atmosphere amongst the Kazakhs at a time when the Russians were facing problems with the Turks and the Bashkirs and had only just conducted the Orenburg Expedition (in 1734) - the first attempt to colonise the steppes. His journal1 1 Into the Kazakh Steppe: John Castle’s Mission to Khan Abulkhayir (1736), Edited by Beatrice Teissier, Signal Books, Oxford, 2014. 1 | P a g e contains the first observations by an Englishman of not just the people, but their religion, customs and society. It contains 13 wonderful plates, showing yourts, the clothing of the Kazakhs, their short beards and moustaches, their animals and their country. These plates are unique. Travellers within what is now modern Kazakhstan – as opposed to through Kazakhstan – were rare. There were no trade links and little diplomatic contact, even through Afghanistan and the North West Frontier. -

“T H E Touch O F Civilization”

Comparing American and Russian “T H E Internal TOU C H Colonization O F CIVILIZatiON” Steven Sabol “THE TOUCH OF CIVILIZATIOn” “THE TOUCH O F CIVILIZATIOn” Comparing American and Russian Internal Colonization Steven Sabol UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of The Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-549-9 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-550-5 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sabol, Steven, author. Title: The touch of civilization : comparing American and Russian internal colonization / Steve Sabol. Description: Boulder, Colorado : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016036164 | ISBN 9781607325499 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325505 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Comparative civilization. | Imperialism—History. | United States—Territorial expansion. | Russia—Territorial expansion. | Collective memory—Russia. | Collective memory—United States. | Dakota Indians—History. | Kazakhs—History. Classification: LCC CB451 .S23 2016 | DDC 909—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036164 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917)

In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross Publisher: Open Book Publishers Year of publication: 2014 Published on OpenEdition Books: 29 November 2016 Serie: OBP collection Electronic ISBN: 9782821876224 http://books.openedition.org Printed version ISBN: 9781783740574 Number of pages: xvi + 432 Electronic reference CROSS, Anthony. In the Lands of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917). New edition [online]. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2014 (generated 19 décembre 2018). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/ obp/2350>. ISBN: 9782821876224. © Open Book Publishers, 2014 Creative Commons - Attribution 4.0 International - CC BY 4.0 ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers IN THE LANDS OF THE ROMANOVS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. -

The Victorian Society in Manchesterregistered Charity No

The Victorian Society in ManchesterRegistered Charity No. 1081435 Registered Charity No.1081435 Winter Newsletter 2015 EDITORIAL January 18th 1966 marked the official launch of the Manchester Group of the Victorian Society, which was held in the Town Hall and attended by the Society's Chairman, Sir Nikolaus Pevsner. Since our next Newsletter will not appear until the Spring we have decided to invite Hilary Grainger and Ken Moth to put down their thoughts in anticipation of that date marking our 50th anniversary, and to whet the appetites of Victorian Society members for the forthcoming celebration of 2016. David Harwood November 2015 MY EARLY DAYS WITH THE MANCHESTER GROUP A personal recollection by Ken Moth This personal recollection of my early years with the Manchester Group sets out to paint a picture of those exciting times. It is not intended to be a comprehensive history – at least that’s my story! Back in 1973, as a nearly qualified architect, I was invited to join other architects in a campaign to save an important textile packing warehouse from demolition. York House on Major Street was designed by Harry Fairhurst in 1911. It had a classical Edwardian facade and a stunning, zigguratical glazed rear, a cascade of glass which seemed The rear of York House, Manchester shortly before demolition in 1974, to anticipate James Stirling’s photograph copyright of Neil Darlington. recent and acclaimed History Faculty at Cambridge University. inquiry, and our task was to show the Victorian Society. John gave a York House, together with J E how similar development objectives detailed and meticulous justification Gregan’s Mechanics Institute of could be achieved whilst retaining of the architectural significance of the 1855, were threatened by a typically the historic buildings. -

Faces of Eurasia

Faces of Eurasia General ● Bruce, Peter Henry, 1692-1757. ● Cook, John, M.D., at Hamilton. Memoirs of Peter Henry Bruce, esq. : a Voyages and travels through the Russian ● Algarotti, Francesco, conte, 1712-1764. military officer in the services of Prussia, empire, Tartary, and part of the kingdom of Letters from Count Algarotti to Lord Hervey Russia, and Great Britain : containing an Persia… and the Marquis Scipio Maffei : containing account of his travels in Germany, Russia, See Central Asia the state of the trade, marine, revenues, and Tartary, Turkey, the West Indies, &c. as also forces of the Russian Empire : with the several very interesting private anecdotes of ● Craven, Elizabeth Craven, Baroness, history of the late war between the Russians the Czar, Peter I. of Russia. 1750-1828. and the Turks, and observations on the Baltic London : Printed for the author's widow, and A journey through the Crimea to and the Caspian seas : to which is added, a sold by T. Payne and son, 1782. Constantinople / in a series of letters from the dissertation on the reigns of the seven kings 446 p. Right Honorable Elizabeth Lady Craven, to of Rome, and a dissertation on the empire of 10 microfiche His Serene Highness the Margrave of the Incas / by the same author ; tr. from the Order no. RT-36 Brandebourg, Anspach, and Bareith ; written Italian ... in the year MDCCLXXXVI. London : Printed for Johnson and Payne, ● Bruin, Cornelis de, 1652-1719. London : Printed for G.G.J. and J. Robinson, 1769. Travels into Muscovy, Persia and part of the 1789. 2 v. -

The Russian Conquest of the Kazakh Steppe by Janet Marie Kilian BA in History, May 1996, Columbia C

Allies & Adversaries: The Russian Conquest of the Kazakh Steppe by Janet Marie Kilian B.A. in History, May 1996, Columbia College, Columbia University M.A. in International Relations & Economics, May 2000, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University M.Phil. in History, May 2007, The George Washington University Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 31, 2013 Dissertation Directed by Muriel Atkin Professor of History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Janet Marie Kilian has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 31, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Allies & Adversaries: The Russian Conquest of the Kazakh Steppe Janet Marie Kilian Dissertation Research Committee: Muriel A. Atkin, Professor of History, Dissertation Director Dane K.Kennedy, Professor of History, Committee Member Andrew Zimmerman, Professor of History, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Janet Marie Kilian All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements It is a great pleasure to count my blessings and acknowledge the assistance I received from so many people and institutions. I would first like to express my deep gratitude and appreciation to my advisor, Muriel Atkin, for her support and guidance throughout this arduous process, and for her faith that I could actually do it. I would also like to thank the other members of my dissertation committee: Dane Kennedy, Andrew Zimmerman, Allen Frank and James Millward.