Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bendigo Tramways It

THE BENDIGO TRUST ANNUAL REPORT, 2009/10 Celebrating 40 years... 37th Edition Annual Report 2009/10 1 I just wanted to let you know ... Just a quick note This was a terrific experience. to say how happy Can’t wait to We (family) enjoyed it more we were with our see the new this was by far my very best party on Friday night. tram museum underground experience than our Ballarat experience. The children had open next year. Janelle Andrew It was very educational. Keep a ball. Your two Day visitor Visiting Friends and Relatives staff members were up the great work! wonderful. Nothing was Vanessa Staying Overnight to much trouble for them. Thank you for John was fabulous. Very making the night a hit. Our Discovery party was fantastic! The kids good with the kids. Nicole Local Knowledge, patience and all had a wonderful time! Very good value only willing to help. The Laurie was for money. Keep up the good work! A really whole fossicking experience brilliant. I will organised party! has been a highlight of be back and suggest JC Local the kids’ school holidays. it to all friends Thank-you Sally Local and family! Anthony Daryl was informative, humorous, an Day Visitor It was the best thing that I have outstanding tour guide! Dean ever done. Day Visitor It was just a great experience Joy It was great. Caitie Day Visitor Local Great staff and service. Excellent upgrade of toilet We really enjoyed it and had a great time. It was the highlight of our the staff were very friendly, helpful and shower holiday so far and knowledgeable. -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

Melbourne Club Members and Daughters Dinner

MELBOURNE CLUB MEMBERS AND DAUGHTERS DINNER Friday 2nd August 2019 Mr Richard Balderstone, Vice President, Melbourne Club Members Daughters, Grand Daughters, God Daughters, Step-Daughters, Daughters-in-Law and Nieces First, I acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land upon which we are gathering and pay my respects to their Elders past and present. A few months ago, I asked a friend, a member of this Club, if he could tell me a little about the history of the Club, as I was preparing to say a few words for this evening’s dinner. I did not understand just how much he would warm to the task, until he delivered to my door, your Club History. That is, what I thought was your Club History. As I blanched under the weight of it, I realised that this was not your Club History as such – at least, not your full Club History. It dealt only with the period 1838 to 1918! Although I could barely lift it, it still had 101 years left to go, just to reach current times! So, please don’t test me on its finer details: I may not have digested every word of it. I did read enough though, to be struck by the Club’s long history, and how it runs parallel with so much of what has occurred across that time in our State. 1 That makes me observe that, similarly, the history of my role runs alongside the last 180 years of what has happened right here and across what later became known as Victoria. -

Heritage Study Stage 2 2003

THEMATIC HISTORY VOLUME 1 City of Ballarat Heritage Study (Stage 2) April 2003: Thematic History 2 City of Ballarat Heritage Study (Stage 2) April 2003: Thematic History TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF APPENDICES iii CONSULTANTS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v OVERVIEW vi INTRODUCTION 1 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING 2 1.TRACING THE EVOLUTION OF THE AUSTRALIAN ENVIRONMENT 2 1.3 Assessing scientifically diverse environments 2 MIGRATING 4 2. PEOPLING AUSTRALIA 4 2.1 Living as Australia's earliest inhabitants 4 2.4 Migrating 4 2.6 Fighting for Land 6 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 7 3. DEVELOPING LOCAL, REGIONAL AND NATIONAL ECONOMIES 7 3.3 Surveying the continent 7 3.4 Utilising natural resources 9 3.5 Developing primary industry 11 3.7 Establishing communications 13 3.8 Moving goods and people 14 3.11 Altering the environment 17 3.14 Developing an Australian engineering and construction industry 19 SETTLING 22 4. BUILDING SETTLEMENTS, TOWNS AND CITIES 22 4.1 Planning urban settlements 22 4.3 Developing institutions 24 LABOUR AND EMPLOYMENT 26 5. WORKING 26 5.1 Working in harsh conditions 26 EDUCATION AND FACILITIES 28 6. EDUCATING 28 6.1 Forming associations, libraries and institutes for self-education 28 6.2 Establishing schools 29 GOVERNMENT 32 i City of Ballarat Heritage Study (Stage 2) April 2003: Thematic History 7. GOVERNING 32 7.2 Developing institutions of self-government and democracy 32 CULTURE AND RECREATION ACTIVITIES 34 8. DEVELOPING AUSTRALIA’S CULTURAL LIFE 34 8.1 Organising recreation 34 8.4 Eating and Drinking 36 8.5 Forming Associations 37 8.6 Worshipping 37 8.8 Remembering the fallen 39 8.9 Commemorating significant events 40 8.10 Pursuing excellence in the arts and sciences 40 8.11 Making Australian folklore 42 LIFE MATTERS 43 9. -

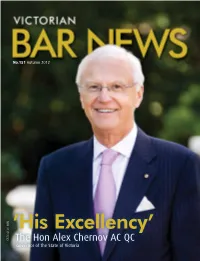

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

1990 Monash University Calendar Vol 2 Parts

M 0 N A S H UNIVERSITY • • 4 • AUSTRALIA Calendar Volume Two 1990 Postal address MONASH UNIVERSITY Clayton Victoria 3168 Telephone (03) 565 4000 lSD (61) (3) 565 4000 Telex AA32691 Fax (61) (3) 565 4007 Visitor HIS EXCELLENCY DR DAVIS McCAUGHEY Governor of Victoria Chancellor THE HoN. SIR GEoRGE HERMANN LusH LLMMelb. Deputy Chancellor JAMES ARNOLD HANCOCK OBE BCom Me/b. FCA AASA Vice-Chancellor MALCOLM IAN LOGAN BA PhD DipEd Syd. FASSA Deputy Vice-Chancellor JoHN ANTHONY HAY MA Cantab. academic BA PhD WAust. FACE Deputy Vice-Chancellor IAN JAMEs PoLMEAR BMetE MSc research DEng Me/b. FTS FIM FIEAust Comptroller PETER BRIAN WADE BCom (Hons) MA Me/b. FASA Registrar ANTHONY LANGLEY PRITCHARD BSc DipEd Me/b. BEd Qld Librarian HucK TEE LIM PKT BA Sing. DipLib N.S. W GradDiplnfSys C. C.A.E. ALAA FLA Faculties and deans Arts RoBERT JOHN PARGETTER BSc MA Me/b. PhD LaT. DipEd Economics and Politics WILLIAM ANGUS SINCLAIR MCom Me/b. DPhil Oxon. FASSA I Education DAVID NICHOLSON AsPIN BA DipEd Durh. I, PhD Nott. FRSA Engineering PETER LEPOER DARVALL BCE Me/b. MS Ohio State MSE MA PhD Prin. DipEd MIEAust I Law CHARLES RoBERT WILLIAMS BCL Oxon. BJuris LLB (Hons) Barrister-at-Law (Vic.) Medicine RoBERT PoRTER BMedSc DSc Adel. MA BCh DM Oxon. FAA FRACP Science WILLIAM RoNALD AYLETT MuNTZ BA DPhil Oxon. FRSE Volume Two 1990 Published by Monash University Clayton Victoria Australia 3168 Typeset by Abb-typesetting Pty Ltd Collingwood Victoria Printed by The Book Printer Maryborough Victoria All rights reserved. This book or any part of it may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever, whether by graphic, visual, electronic, filming, microfilming, tape recording or any means, except in the case of brief passages for the information of students, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No

VICTORIAN No. 121 ISSN 0150-3285BAR NEWS WINTER 2002 Launch of the New County Court Welcome: Justice Robert Osborn Farewell: The Honourable Professor Robert Brooking QC Allayne Kiddle: Victoria’s Third Woman Barrister’s Refl ections on Her Life at the Bar Mr Junior Silk’s Speech to the Annual Bar Dinner Response to Junior Silk on Behalf of Judiciary at Bar Dinner Justice Sally Brown Unveiled R v Ryan ReprieveAustralia’s US Mission Revisited The Zucchini Flower of Queen Street Annual Box Trophy 3 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 121 WINTER 2002 Contents EDITORS’ BACKSHEET 5 A New County Court and New Insurance Premiums ACTING CHAIRMAN’S CUPBOARD 7 Laws of Negligence — Where to Now? ATTORNEY-GENERAL’S COLUMN 9 Autumn Session Reforms PRACTICE PAGE 11 Amendment to the Rules of Conduct 13 Professional Indemnity Insurance for Former Barristers CORRESPONDENCE 14 Letter to the Editors Welcome: Justice Robert Osborn Farewell: The Honourable Professor Robert Brooking QC WELCOME 15 Justice Robert Osborn FAREWELL 16 The Honourable Professor Robert Brooking QC ARTICLES 21 Launch of the New County Court of Victoria 32 Allayne Kiddle: Victoria’s Third Women Barrister’s Reflections on Her Life at the Bar NEWS AND VIEWS 40 Verbatim 41 Mr Junior Silk’s Speech to the Annual Bar Mr Junior Silk’s Speech to the Dinner Annual Bar Dinner 48 Response to Junior Silk on Behalf of Judiciary at Bar Dinner 50 R v Ryan 51 Justice Sally Brown Unveiled 52 ReprieveAustralia’s US Mission Revisited 52 Lethal Lawyers 55 Union Confidence Justice 56 Angola 56 Choosing Death 58 The Gift of Time 59 A Bit About Words/Doublespeak 61 Lunch/Caterina’s Cucina: The Zucchini Flower Allayne Kiddle Justice Sally Brown Unveiled of Queen Street SPORT 62 Royal Tennis/Annual Box Trophy LAWYER’S BOOKSHELF 63 Books Reviewed 66 CONFERENCE UPDATE Cover: The new County Court building — the new face of justice. -

Retirement of Commander the Honourable John Winneke AC RFD RANR

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 133 ISSN 0159-3285 WINTER 2005 Retirement of Commander The Honourable John Winneke AC RFD RANR Legal Profession Act 2004 Disclosure Requirements and Cost Agreements Under the Legal Profession Act 2004 Farewell Anna Whitney Obituaries: James Anthony Logan, Carl Price and Brian Thomson QC Junior Silk’s Bar Dinner Speech Reply on Behalf of the Honoured Guests to the Speech of Mr Junior Silk The Thin End of the Wedge Opening of the Refurbished Owen Dixon Chambers East The Revolution of 1952 — Or the Origins of ODC Of Stuff and Silk Peter Rosenberg Congratulates the Prince on His Marriage The Ways of a Jury Bar Legal Assistance Committee A Much Speaking Judge is like an Ill-tuned Cymbal March 1985 Readers’ Group 20th Anniversary Dinner Aboriginal Law Students Mentoring Committee Court Network’s 25th Anniversary Au Revoir, Hartog Modern Future for Victoria’s Historic Legal Precinct Preparation for Mediation: Playing the Devil’s Advocate Is It ’Cos I Is Black (Or Is It ’Cos I Is Well Fit For It)? What you do with the time you’ll save is your business Find it fast with our new online legal information service With its speed and up-to-date information, no wonder so With a range of packages to choose from, you can many legal professionals are subscribing to LexisNexis AU, customise the service precisely to the needs of your practice. our new online legal information service. You can choose And you’ll love our approach to online searching – we’ve from over 100 works, spanning 16 areas of the law – plus made it incredibly easy to use, with advanced emailing and reference and research works including CaseBase, Australian printing capabilities. -

Report on the Judicial Conduct and Complaints System in Victoria

THE JUDICIAL CONDUCT AND COMPLAINTS SYSTEM IN VICTORIA A REPORT Professor Peter A Sallmann Crown Counsel for Victoria Dec 2003 Dedication This report is dedicated to the memory of the late Richard E McGarvie AC QC, leading barrister, Supreme Court Judge, University Chancellor, Governor of Victoria and noted constitutional and political reformer, who made a huge contribution to the conduct of public affairs in Australia. Of special significance in the context of this report is his substantial influence on the development of the judicial branch of government in Australia and judicial administration in general. He was a member of the Judicial System Committee of the Constitutional Commission, a founding father of both the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration (AIJA) and the Judicial Conference of Australia (JCA) and, through a host of inquiries and committees, led many significant judicial administration reform initiatives. His numerous papers and published articles on key aspects of judicial administration are standard reading for students and judicial system practitioners alike. Richard McGarvie, who died in May this year, and the author of this report were good friends and judicial administration colleagues. They worked closely together on a number of justice system projects over the years. He contributed significantly to this particular report by providing various ideas and suggestions at key stages of the review. P.S. The Judicial Conduct and Complaints System in Victoria: A Report 2 About the Author Peter Sallmann is Crown Counsel for Victoria. He was the inaugural Executive Director of the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration (AIJA) from 1987-96 and before that he taught law and criminal justice at La Trobe University, and was a full-time Commissioner with the Law Reform Commission of Victoria. -

DALKIN, ROBERT NIXON (BOB) (1914–1991), Air Force Officer

D DALKIN, ROBERT NIXON (BOB) (1960–61), staff officer operations, Home (1914–1991), air force officer and territory Command (1957–59), and officer commanding administrator, was born on 21 February 1914 the RAAF Base, Williamtown, New South at Whitley Bay, Northumberland, England, Wales (1963). He had graduated from the RAF younger son of English-born parents George Staff College (1950) and the Imperial Defence Nixon Dalkin, rent collector, and his wife College (1962). Simultaneously, he maintained Jennie, née Porter. The family migrated operational proficiency, flying Canberra to Australia in 1929. During the 1930s bombers and Sabre fighters. Robert served in the Militia, was briefly At his own request Dalkin retired with a member of the right-wing New Guard, the rank of honorary air commodore from the and became business manager (1936–40) for RAAF on 4 July 1968 to become administrator W. R. Carpenter [q.v.7] & Co. (Aviation), (1968–72) of Norfolk Island. His tenure New Guinea, where he gained a commercial coincided with a number of important issues, pilot’s licence. Described as ‘tall, lean, dark including changes in taxation, the expansion and impressive [with a] well-developed of tourism, and an examination of the special sense of humour, and a natural, easy charm’ position held by islanders. (NAA A12372), Dalkin enlisted in the Royal Dalkin overcame a modest school Australian Air Force (RAAF) on 8 January education to study at The Australian National 1940 and was commissioned on 4 May. After University (BA, 1965; MA, 1978). Following a period instructing he was posted to No. 2 retirement, he wrote Colonial Era Cemetery of Squadron, Laverton, Victoria, where he Norfolk Island (1974) and his (unpublished) captained Lockheed Hudson light bombers on memoirs. -

Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 10

Chapter One A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Referendum Sir David Smith, KCVO, AO On Friday, 13 February, 1998, in the House of Representatives Chamber of Old Parliament House, Canberra, republican delegates to the 1998 Constitutional Convention began to clap and cheer and embrace each other as the vote on the final resolution was taken. Spectators in the public gallery stood and cheered with them. But in the months that have followed, the republican euphoria has dimmed, even for some who had so enthusiastically joined in the clapping and the cheering and the embracing back in February. Not only have some of them predicted that the referendum to turn this country into a republic will fail: some have even dared to suggest that it will be a disaster for Australia if the referendum is carried. The final resolution recommended to the Prime Minister and the Parliament that the republican model supported by the Convention be put to the people in a constitutional referendum. This resolution received the votes of 133 of the 152 delegates. It was supported by delegates representing Australians for Constitutional Monarchy because we, too, want the issue of the republic settled once and for all. We welcome the opportunity to have it taken out of the hands of the various elites who have controlled and stifled the debate to date, and to have it put to the Australian people.1 Of more significance was the preceding resolution, which called for the Convention to support the adoption of the Turnbull republican model in preference to our present constitutional arrangements. -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS ISSUE 161 WINTER 2017 VICTORIAN a Fiery Start to the Bar BAR Cliff Pannam Spies Like Us NEWS Stephen Charles

161 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS BAR VICTORIAN ISSUE 161 WINTER 2017 VICTORIAN A fiery start to the Bar BAR Cliff Pannam Spies like us NEWS Stephen Charles Remembering Ronald Ryan Masterpiece Bill Henson work unveiled WINTER 2017 161 At the Glasshouse: The Bar dinner photographs ISSUE 161 WINTER 2017 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS Editorial 44 Milky Way Dreaming KRISTINE HANSCOMBE QC Not the 24 hour news cycle 3 THE EDITORS 46 Innovate, regulate: Michael McGarvie, Victorian Legal Letters to the editors 5 Services Commissioner President’s report 6 GEORGINA COSTELLO AND JESSE RUDD JENNIFER BATROUNEY QC 20 Around town Bar Lore 2017 Victorian Bar Dinner 8 52 A Fiery start at the Bar — Indigenous Justice 14 some fifty years ago Committee RAP event DR CLIFF PANNAM QC SALLY BODMAN 58 Remembering Ronald Ryan George Hampel AM QC 16 KERRI RYAN ELIZABETH BRIMER 62 Where there’s a will, we’ll go a Henson portrait of the Hon 20 Waltzing Matilda: Serendipity Ken Hayne AC QC in chambers SIOBHAN RYAN W. BENJAMIN LINDNER Supreme Court of Victoria 24 v Australian Cricket Society 8 Back of the Lift THE HON DAVID HARPER AM 66 Adjourned Sine Die Bar, Bench and Solicitors golf day 27 67 Silence all stand CAROLINE PATTERSON 46 68 Vale News and Views 76 Gonged Volunteering at the Capital 28 77 Victorian Bar Readers Post-Conviction Project of Louisiana Boilerplate NATALIE HICKEY 78 A bit about words JULIAN BURNSIDE QC The David Combe affair 31 THE HON STEPHEN CHARLES AO QC 80 Off the Wall SIOBHÁN RYAN The Judicial College 38 82 Red Bag Blue Bag of Victoria master of its fate 83 The