Report on the Judicial Conduct and Complaints System in Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

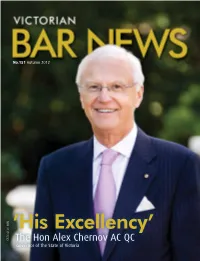

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No

VICTORIAN No. 121 ISSN 0150-3285BAR NEWS WINTER 2002 Launch of the New County Court Welcome: Justice Robert Osborn Farewell: The Honourable Professor Robert Brooking QC Allayne Kiddle: Victoria’s Third Woman Barrister’s Refl ections on Her Life at the Bar Mr Junior Silk’s Speech to the Annual Bar Dinner Response to Junior Silk on Behalf of Judiciary at Bar Dinner Justice Sally Brown Unveiled R v Ryan ReprieveAustralia’s US Mission Revisited The Zucchini Flower of Queen Street Annual Box Trophy 3 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 121 WINTER 2002 Contents EDITORS’ BACKSHEET 5 A New County Court and New Insurance Premiums ACTING CHAIRMAN’S CUPBOARD 7 Laws of Negligence — Where to Now? ATTORNEY-GENERAL’S COLUMN 9 Autumn Session Reforms PRACTICE PAGE 11 Amendment to the Rules of Conduct 13 Professional Indemnity Insurance for Former Barristers CORRESPONDENCE 14 Letter to the Editors Welcome: Justice Robert Osborn Farewell: The Honourable Professor Robert Brooking QC WELCOME 15 Justice Robert Osborn FAREWELL 16 The Honourable Professor Robert Brooking QC ARTICLES 21 Launch of the New County Court of Victoria 32 Allayne Kiddle: Victoria’s Third Women Barrister’s Reflections on Her Life at the Bar NEWS AND VIEWS 40 Verbatim 41 Mr Junior Silk’s Speech to the Annual Bar Mr Junior Silk’s Speech to the Dinner Annual Bar Dinner 48 Response to Junior Silk on Behalf of Judiciary at Bar Dinner 50 R v Ryan 51 Justice Sally Brown Unveiled 52 ReprieveAustralia’s US Mission Revisited 52 Lethal Lawyers 55 Union Confidence Justice 56 Angola 56 Choosing Death 58 The Gift of Time 59 A Bit About Words/Doublespeak 61 Lunch/Caterina’s Cucina: The Zucchini Flower Allayne Kiddle Justice Sally Brown Unveiled of Queen Street SPORT 62 Royal Tennis/Annual Box Trophy LAWYER’S BOOKSHELF 63 Books Reviewed 66 CONFERENCE UPDATE Cover: The new County Court building — the new face of justice. -

Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 10

Chapter One A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Referendum Sir David Smith, KCVO, AO On Friday, 13 February, 1998, in the House of Representatives Chamber of Old Parliament House, Canberra, republican delegates to the 1998 Constitutional Convention began to clap and cheer and embrace each other as the vote on the final resolution was taken. Spectators in the public gallery stood and cheered with them. But in the months that have followed, the republican euphoria has dimmed, even for some who had so enthusiastically joined in the clapping and the cheering and the embracing back in February. Not only have some of them predicted that the referendum to turn this country into a republic will fail: some have even dared to suggest that it will be a disaster for Australia if the referendum is carried. The final resolution recommended to the Prime Minister and the Parliament that the republican model supported by the Convention be put to the people in a constitutional referendum. This resolution received the votes of 133 of the 152 delegates. It was supported by delegates representing Australians for Constitutional Monarchy because we, too, want the issue of the republic settled once and for all. We welcome the opportunity to have it taken out of the hands of the various elites who have controlled and stifled the debate to date, and to have it put to the Australian people.1 Of more significance was the preceding resolution, which called for the Convention to support the adoption of the Turnbull republican model in preference to our present constitutional arrangements. -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS ISSUE 161 WINTER 2017 VICTORIAN a Fiery Start to the Bar BAR Cliff Pannam Spies Like Us NEWS Stephen Charles

161 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS BAR VICTORIAN ISSUE 161 WINTER 2017 VICTORIAN A fiery start to the Bar BAR Cliff Pannam Spies like us NEWS Stephen Charles Remembering Ronald Ryan Masterpiece Bill Henson work unveiled WINTER 2017 161 At the Glasshouse: The Bar dinner photographs ISSUE 161 WINTER 2017 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS Editorial 44 Milky Way Dreaming KRISTINE HANSCOMBE QC Not the 24 hour news cycle 3 THE EDITORS 46 Innovate, regulate: Michael McGarvie, Victorian Legal Letters to the editors 5 Services Commissioner President’s report 6 GEORGINA COSTELLO AND JESSE RUDD JENNIFER BATROUNEY QC 20 Around town Bar Lore 2017 Victorian Bar Dinner 8 52 A Fiery start at the Bar — Indigenous Justice 14 some fifty years ago Committee RAP event DR CLIFF PANNAM QC SALLY BODMAN 58 Remembering Ronald Ryan George Hampel AM QC 16 KERRI RYAN ELIZABETH BRIMER 62 Where there’s a will, we’ll go a Henson portrait of the Hon 20 Waltzing Matilda: Serendipity Ken Hayne AC QC in chambers SIOBHAN RYAN W. BENJAMIN LINDNER Supreme Court of Victoria 24 v Australian Cricket Society 8 Back of the Lift THE HON DAVID HARPER AM 66 Adjourned Sine Die Bar, Bench and Solicitors golf day 27 67 Silence all stand CAROLINE PATTERSON 46 68 Vale News and Views 76 Gonged Volunteering at the Capital 28 77 Victorian Bar Readers Post-Conviction Project of Louisiana Boilerplate NATALIE HICKEY 78 A bit about words JULIAN BURNSIDE QC The David Combe affair 31 THE HON STEPHEN CHARLES AO QC 80 Off the Wall SIOBHÁN RYAN The Judicial College 38 82 Red Bag Blue Bag of Victoria master of its fate 83 The -

30 June 2007 3 Annual Report of the Victorian Bar Inc for the Year Ended 30 June 2007

The Victorian Bar Inc Reg. No. A0034304S ANNUAL REPORT 1 July 2006 – 30 June 2007 3 Annual Report of The Victorian Bar Inc for the Year Ended 30 June 2007 To be presented to the Annual General Meeting of The Victorian Bar Inc to be held at 5.00 pm on Monday 17 September 2007 in the Neil McPhee Room, Level 1, Owen Dixon Chambers East, 205 William Street, Melbourne. Victorian Bar Council In the annual election held in September 2006, the following members of counsel were elected: Category A: Eleven (11) counsel who are Queen’s Counsel or Senior Counsel or are of not less than fifteen (15) years’ standing Jacob (Jack) I Fajgenbaum QC G John Digby QC G (Tony) Pagone QC Michael W Shand QC Michael J Colbran QC Paul G Lacava S.C. Timothy P Tobin S.C. Peter J Riordan S.C. Fiona M McLeod S.C. Richard W McGarvie S.C. Dr David J Neal S.C. Category B: Six (6) counsel who are not of Queen’s Counsel or Senior Counsel and are of not more than fifteen (15) nor less than six (6) years’ standing Kerri E Judd E William Alstergren Mark K Moshinsky P Justin Hannebery Cahal G Fairfield Charles E Shaw Category C: Four (4) counsel who are not of Queen’s Counsel or Senior Counsel and are of less than six (6) years’ standing Katharine J D Anderson Anthony G Burns Daniel C Harrison Dr Michelle R Sharpe 3 THE VICTORIAN BAR INC ANNUAL REPORT Contents Page Chairman’s Report 5 Officers of the Bar Council 18 Bar Companies and Associations 19 Standing Committees of the Bar Council 21 Joint Standing Committees 25 Bar Appointees 26 General Meetings 32 Personalia 34 Roll of Counsel 38 Functions 44 Sporting Events 46 Annual Reports of Associations and Committees 49 Financial Report i The Victorian Bar Inc Owen Dixon Chambers East 205 William Street, Melbourne 3000 Phone: 9225 7111 Fax: 9225 6068 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vicbar.com.au 4 5 Chairman’s Report The tradition of service by members This Bar has a proud tradition of voluntary service by members. -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No

VICTORIAN No. 139 ISSN 0159-3285BAR NEWS SUMMER 2006 Appointment of Senior Counsel Welcomes: Justice Elizabeth Curtain, Judge Anthony Howard, Judge David Parsons, Judge Damien Murphy, Judge Lisa Hannon and Magistrate Frank Turner Farewell: Judge Barton Stott Charles Francis Talks of County Court Judges of Yesteryear Postcard from New York City Bar Welcomes Readers Class of 2006 Milestone for the Victorian Bar 2006–2007 Victorian Bar Council Appointment and Retirement of Barfund Board Directors Celebrating Excellence Retiring Chairman’s Dinner Women’s Legal Service Victoria Celebrates 25 Years Fratricide in Labassa Launch of the Good Conduct Guide Extending the Boundary of Right Council of Legal Education Dinner Women Barristers Association Anniversary Dinner A Cricket Story The Essoign Wine Report A Bit About Words/The King’s English Bar Hockey 3 ���������������������������������� �������������������� VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 139 SUMMER 2006 Contents EDITORS’ BACKSHEET 5 Something Lost, Something Gained 6 Appointment of Senior Counsel CHAIRMAN’S CUPBOARD 7 The Bar — What Should We be About? ATTORNEY-GENERAL’S COLUMN 9 Taking the Legal System to Even Stronger Ground Welcome: Justice Welcome: Judge Anthony Welcome: Judge David WELCOMES Elizabeth Curtain Howard Parsons 10 Justice Elizabeth Curtain 11 Judge Anthony Howard 12 Judge David Parsons 13 Judge Damien Murphy 14 Judge Lisa Hannon 15 Magistrate Frank Turner FAREWELL 16 Judge Barton Stott NEWS AND VIEWS 17 Charles Francis Talks of County Court Judges Welcome: Judge Damien Welcome: Judge -

27 October 1992 to 13 November 1992J

VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) FIFTY-SECOND PARLIAMENT SPRING SESSION 1992 Legislative Assembly VOL. 409 [From 27 October 1992 to 13 November 1992J MELBOURNE: L. V. NORTIl, GOVERNMENT PRINTER The Governor His Excellency the Honourable RICHARD E. McGARVIE The Lieutenant-Governor His Excellency the Honourable SIR JOHN McINTOSH YOUNG, AC, KCMG The Ministry [AS FROM 6 OCTOBER 1992] Premier, and Minister for Ethnic Affairs .... The Hon.]. G. Kennett, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Police and ... The Hon. P. J. McNamara, MP Emergency Services, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Tourism, and Minister for Agriculture Minister for Industry and Employment,. .. The Hon. P. A. Gude, MP Minister for Industry Services, Minister for Small Business, and Minister for Youth Affairs Minister for Roads and Ports ............. The Hon. W. R. Baxter, MLC Minister for Conservation and Environment, The Hon. M. A. Birrell, MLC and Minister for Major Projects Minister for Public Transport .. , .......... The Hon. A. J. Brown, MP Minister for Natural Resources ............ The Hon. C. G. Coleman, MP Minister for Regional Development, . .. The Hon. R. M. Hallam, MLC Minister for Local Government, and Minister responsible for WorkCare Minister for Education. .. The Hon. D. K. Hayward, MP Minister for Housing, and Minister for. .. The Hon. R. I. Knowles, MLC Aged Care Minister for Planning .................. " The Hon. R. R. C. Maclellan, MP Minister for Energy and Minerals, and. .. The Hon. S. J. Plowman, MP Minister Assisting the Treasurer on State Owned Enterprises Minister for Sport, Recreation and Racing.. The Hon. T. C. Reynolds, MP Minister for Finance ..................... The Hon. I. W. Smith, MP Treasurer ............................ " The Hon. A. -

Book 9 3, 4 and 5 June 2003

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 9 3, 4 and 5 June 2003 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au\downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister -

Going to Court

GOING TO COURT A DISCUSSION PAPER ON CIVIL JUSTICE IN VICTORIA PETER A SALLMANN, CROWN COUNSEL AND RICHARD T WRIGHT, ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, CIVIL JUSTICE REVIEW PROJECT APRIL, 2000 How to make comments and submissions We would encourage comments and submissions on the discussion paper. They can be sent to the Department of Justice at the address below: Civil Justice Review Project GPO Box 4356QQ Melbourne, Victoria, 3001 Comments and submissions can also be sent by e-mail to: [email protected] The discussion can be read and downloaded from the Department of Justice homepage www.justice.vic.gov.au Adobe Acrobat® Reader will be required. Peter Sallmann LLB (Melbourne), M.S.A.J. (The American University), M.Phil (Cambridge) is Victorian Crown Counsel, formerly Director of the Civil Justice Review Project, Executive Director of the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration and a Commissioner of the Law Reform Commission of Victoria. Peter is admitted to practise as a Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Victoria. He has held a number of academic posts in law and criminology, and served on a variety of Boards and Inquiries, including the Premier’s Drug Advisory Council (the Penington Inquiry) and has published widely on judicial administration and related topics. Richard Wright B.Ec (Hons) (La Trobe) LLB (Melbourne) is Associate Director of the Civil Justice Review Project, formerly Chairman of the Residential Tenancies Tribunals and Senior Referee of the Small Claims Tribunal, Executive Director of the Law Reform Commission of Victoria, Management Consultant in the public and private sectors and has held policy advisory positions in the Australian Tariff Board, Prices Justification Tribunal and the federal Departments of Industrial Relations and Prime Minister and Cabinet. -

Royal Assent in Victoria

Royal Assent in Victoria # Kate Murray * In October 2005 the Governor of Victoria withheld the royal assent from a bill on advice from the Premier. This caused private concern for parliamentary staff, outspoken complaints from some members of Parliament and even somewhat of a media frenzy — well a frenzy relative to the usual media attention paid to parliamentary procedure. The withholding of assent led to a range of questions. What exactly is the legal and constitutional basis for royal assent in Victoria? How has the procedure for giving assent changed over the 150 year history of the Parliament of Victoria? What are the roles of the clerk of the parliaments, the governor and the executive in the process and, in particular, who can and should advise the governor? This paper will attempt to answer some of those questions and examine a range of situations in which there have been difficulties with the royal assent process in Victoria. New comers to the Victorian Constitution might be surprised to find that it is not a ‘how to’ on democracy in Victoria. Much of what happens in the three branches of government and the relationships between them is left unsaid. 1 Instead the traditions of the Westminster system, together with various adaptations developed during the 150 years of responsible government in Victoria, are followed. And so it is with the process for royal assent. Royal assent is one of the stages of making a law in Victoria. It occurs when the governor, on behalf of the Queen, approves a bill that has been passed by both Houses of Parliament. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abbey, B. (1987) ‘Power, Politics and Business’, Australian Journal of Political Science, 22 (2), 46–54. Ackerman, B. (2000) ‘The New Separation of Powers’, Harvard Law Review, 113 (3), 633–729. ADB (2008) Australian Dictionary of Biography Online Edition, at http://www.adb.online.anu. edu.au/adbonline.htm, accessed 29 July 2008. Adcock, R., M. Bevir and S. Stimson (eds) (2006a) Modern Political Science: Anglo-American Exchanges since 1880 (Princeton: Princeton University Press). ——— (2006b) ‘A History of Political Science. How? What? Why?’, in R. Adcock, M. Bevir and S. Stimson (eds), Modern Political Science, 1–17. Adelman, H., A. Borowski, M. Burstein and L. Foster (eds) (1994) Immigration and Refugee Policy: Australia and Canada Compared, 2 vols (Carlton: Melbourne University Press). Adeney, D. (1986) ‘Machiavelli and Political Morals’, in David Muschamp (ed.), Political Thinkers (South Melbourne: Macmillan), 51–65. Adorno, T. W., E. Frenkel-Brunswik, D. J. Levinson, and R. N. Sanford (1950) The Authoritarian Personality (New York: Harper and Row). Ahluwalia, P. (2001b) ‘When Does a Settler Become a Native? Citizenship and Identity in a Settler Society’, Pretexts, 10 (1), 63–73. Aimer, P. (1974) Politics, Power and Persuasion: The Liberals in Victoria (Sydney: James Bennett). Aitkin, D. (1969) The Colonel: A Political Biography of Sir Michael Bruxner (Canberra: Australian National University Press). ——— (1972a) The Country Party in New South Wales: A Study of Organisation and Survival (Canberra: Australian National University Press). ——— (1972b) ‘Perceptions of Partisan Bias in the Australian Mass Media’, Politics, VII (2), 160–9. ——— (1977) Stability and Change in Australian Politics (Canberra: Australian National University Press).