Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margaret Klaassen Thesis (PDF 1MB)

AN EXAMINATION OF HOW THE MILITARY, THE CONSERVATIVE PRESS AND MINISTERIALIST POLITICIANS GENERATED SUPPORT WITHIN QUEENSLAND FOR THE WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA IN 1899 AND 1900 Margaret Jean Klaassen ASDA, ATCL, LTCL, FTCL, BA 1988 Triple Majors: Education, English & History, University of Auckland. The University Prize in Education of Adults awarded by the Council of the University of Auckland, 1985. Submitted in full requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Division of Research & Commercialisation Queensland University of Technology 2014 Keywords Anglo-Boer War, Boer, Brisbane Courier, Dawson, Dickson, Kitchener, Kruger, Orange Free State, Philp, Queensland, Queenslander, Transvaal, War. ii Abstract This thesis examines the myth that Queensland was the first colonial government to offer troops to support England in the fight against the Boers in the Transvaal and Orange Free State in 1899. The offer was unconstitutional because on 10 July 1899, the Premier made it in response to a request from the Commandant and senior officers of the Queensland Defence Force that ‘in the event of war breaking out in South Africa the Colony of Queensland could send a contingent of troops and a machine gun’. War was not declared until 10 October 1899. Under Westminster government conventions, the Commandant’s request for military intervention in an overseas war should have been discussed by the elected legislators in the House. However, Parliament had gone into recess on 24 June following the Federation debate. During the critical 10-week period, the politicians were in their electorates preparing for the Federation Referendum on 2 September 1899, after which Parliament would resume. -

Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 1

Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society Inaugural Conference Hillton-on-the-Park, Melbourne; 24 - 26 July 1992 Copyright 1992 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society ________________________________________ 1 Foreword John Stone___________________________________________________________________ 4 Launching Address Re-Writing the Constitution Sir Harry Gibbs, GCMG, AC, KBE _______________________________________________ 5 Inaugural Address Right According to Law The Hon Peter Connolly, CBE, QC ______________________________________________ 11 Introductory Remarks John Stone__________________________________________________________________ 15 Chapter One The Australian Constitution: A Living Document H M Morgan ________________________________________________________________ 17 Chapter Two Constitutions and The Constitution S.E.K. Hulme________________________________________________________________ 26 Chapter Three Constitutional Reform: The Tortoise or the Hare? Greg Craven ________________________________________________________________ 39 Chapter Four Keeping Government at Bay: The Case for a Bill of Rights Frank Devine________________________________________________________________ 46 Chapter Five Financial Centralisation: The Lion in the Path David Chessell _______________________________________________________________ 55 Chapter Six The High Court - The Centralist Tendency L J M Cooray________________________________________________________________ 62 Chapter -

Justice Richard O'connor and Federation Richard Edward O

1 By Patrick O’Sullivan Justice Richard O’Connor and Federation Richard Edward O’Connor was born 4 August 1854 in Glebe, New South Wales, to Richard O’Connor and Mary-Anne O’Connor, née Harnett (Rutledge 1988). The third son in the family (Rutledge 1988) to a highly accomplished father, Australian-born in a young country of – particularly Irish – immigrants, a country struggling to forge itself an identity, he felt driven to achieve. Contemporaries noted his personable nature and disarming geniality (Rutledge 1988) like his lifelong friend Edmund Barton and, again like Barton, O’Connor was to go on to be a key player in the Federation of the Australian colonies, particularly the drafting of the Constitution and the establishment of the High Court of Australia. Richard O’Connor Snr, his father, was a devout Roman Catholic who contributed greatly to the growth of Church and public facilities in Australia, principally in the Sydney area (Jeckeln 1974). Educated, cultured, and trained in multiple instruments (Jeckeln 1974), O’Connor placed great emphasis on learning in a young man’s life and this is reflected in the years his son spent attaining a rounded and varied education; under Catholic instruction at St Mary’s College, Lyndhurst for six years, before completing his higher education at the non- denominational Sydney Grammar School in 1867 where young Richard O’Connor met and befriended Edmund Barton (Rutledge 1988). He went on to study at the University of Sydney, attaining a Bachelor of Arts in 1871 and Master of Arts in 1873, residing at St John’s College (of which his father was a founding fellow) during this period. -

Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention

The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention* Geoffrey Bolton dmund Barton first entered my life at the Port Hotel, Derby on the evening of Saturday, E13 September 1952. As a very young postgraduate I was spending three months in the Kimberley district of Western Australia researching the history of the pastoral industry. Being at a loose end that evening I went to the bar to see if I could find some old-timer with an interesting store of yarns. I soon found my old-timer. He was a leathery, weather-beaten station cook, seventy-three years of age; Russel Ward would have been proud of him. I sipped my beer, and he drained his creme-de-menthe from five-ounce glasses, and presently he said: ‘Do you know what was the greatest moment of my life?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘but I’d like to hear’; I expected to hear some epic of droving, or possibly an anecdote of Gallipoli or the Somme. But he answered: ‘When I was eighteen years old I was kitchen-boy at Petty’s Hotel in Sydney when the federal convention was on. And every evening Edmund Barton would bring some of the delegates around to have dinner and talk about things. I seen them all: Deakin, Reid, Forrest, I seen them all. But the prince of them all was Edmund Barton.’ It struck me then as remarkable that such an archetypal bushie, should be so admiring of an essentially urban, middle-class lawyer such as Barton. -

The Politics of Expediency Queensland

THE POLITICS OF EXPEDIENCY QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT IN THE EIGHTEEN-NINETIES by Jacqueline Mc0ormack University of Queensland, 197^1. Presented In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts to the Department of History, University of Queensland. TABLE OP, CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION SECTION ONE; THE SUBSTANCE OP POLITICS CHAPTER 1. The Men of Politics 1 CHAPTER 2. Politics in the Eighties 21 CHAPTER 3. The Depression 62 CHAPTER 4. Railways 86 CHAPTER 5. Land, Labour & Immigration 102 CHAPTER 6 Separation and Federation 132 CHAPTER 7 The Queensland.National Bank 163 SECTION TWO: THE POLITICS OP REALIGNMENT CHAPTER 8. The General Election of 1888 182 CHAPTER 9. The Coalition of 1890 204 CHAPTER 10. Party Organization 224 CHAPTER 11. The Retreat of Liberalism 239 CHAPTER 12. The 1893 Election 263 SECTION THREE: THE POLITICS.OF EXPEDIENCY CHAPTER 13. The First Nelson Government 283 CHAPTER Ik. The General Election of I896 310 CHAPTER 15. For Want of an Opposition 350 CHAPTER 16. The 1899 Election 350 CHAPTER 17. The Morgan-Browne Coalition 362 CONCLUSION 389 APPENDICES 394 BIBLIOGRAPHY 422 PREFACE The "Nifi^ties" Ms always" exercised a fascination for Australian historians. The decade saw a flowering of Australian literature. It saw tremendous social and economic changes. Partly as a result of these changes, these years saw the rise of a new force in Australian politics - the labour movement. In some colonies, this development was overshadowed by the consolidation of a colonial liberal tradition reaching its culmination in the Deakinite liberalism of the early years of the tlommdhwealth. Developments in Queensland differed from those in the southern colonies. -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

The Mount Mulligan Coal Mine Disaster of 1921, Boolarong Press, Brisbane, 2013

Journal of Australasian Mining History, Volume 11, October 2013 Book Reviews Peter Bell, Alas it Seems Cruel: The Mount Mulligan Coal Mine Disaster of 1921, Boolarong Press, Brisbane, 2013. Pp. 301. ISBN 0-7083-2611-4. istorian and Adelaide-based heritage consultant Peter Bell gets straight to the point. “This is the story of a horrible event in a remote and beautiful location H ninety years ago,” he writes in his introduction. Many will be familiar with Bell’s earlier, and excellent, examinations of the 19 September, 1921, Mount Mulligan Mine Disaster. The terrible event claimed 75, possibly 76, lives. Initially produced as a history honours thesis at James Cook University in 1977 and published as a monograph one year later, the Mount Mulligan work was reprinted in 1996 to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of the tragedy. This latest 2013 publication, basically a third edition, comes with Bell’s observation: “This book has evolved over those years. But it has not changed fundamentally. I have learned a little more, corrected some errors, changed some emphases, and I may have become a little bit more forthright in attributing praise or blame, but the story is essentially the same.” In brief, that story attends to the reasons for the establishment of the mine at Mount Mulligan in Far North Queensland, the appearance of the small settlement around the mine, conditions at the mine, the explosion that claimed so many lives and the brave efforts of those who searched for survivors and then recovered bodies after the carnage. As in the original publication, this third iteration deals with the post-disaster fortunes and misfortunes of the mine and the Mount Mulligan township and the eventual demise of coal mining at Mount Mulligan. -

Papers of Sir Edmund Barton Ms51

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA PAPERS OF SIR EDMUND BARTON MS51 Manuscript Collection 1968-70, 1996 and last amended 2001 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview 3 Biographical Note 6 Related Material 8 Microfilms 9 Series Description 10 Series 1: Correspondence 1827-1921 10 Series 2: Diaries, 1869, 1902-03 39 Series 3: Personal documents 1828-1939, 1844 39 Series 4: Commissions, patents 1891-1903 40 Series 5: Speeches, articles 1898-1901 40 Series 6: Papers relating to the Federation Campaign 1890-1901 41 Series 7: Other political papers 1892-1911 43 Series 8: Notes, extracts 1835-1903 44 Series 9: Newspaper cuttings 1894-1917 45 Series 10: Programs, menus, pamphlets 1883-1910 45 Series 11: High Court of Australia 1903-1905 46 Series 12: Photographs (now in Pictorial Section) 46 Series 13: Objects 47 Name Index of Correspondence 48 Box List 61 2 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 Overview This is a Guide to the Papers of Sir Edmund Barton held in the Manuscript Collection of the National Library of Australia. As well as using this guide to browse the content of the collection, you will also find links to online copies of collection items. Scope and Content The collection consists of correspondence, personal papers, press cuttings, photographs and papers relating to the Federation campaign and the first Parliament of the Commonwealth. Correspondence 1827-1896 relates mainly to the business and family affairs of William Barton, and to Edmund's early legal and political work. Correspondence 1898-1905 concerns the Federation campaign, the London conference 1900 and Barton's Prime Ministership, 1901-1903. -

GRIFFITH LIVES on This Is a Great Honour

43 THIRD CLEM LACK MEMORIAL ORATION delivered to the Royal Historical Society of Queensland by Sir Theodor Bray, Chakman of Griffith University Council, at Newstead House, 20 March 1975. GRIFFITH LIVES ON This is a great honour. I deeply appreciate the tribute you pay me in asking me to deliver the Clem Lack Oration for 1975. This is not an oration: it is a talk on the subject "Griffith Lives On", and is devoted to the life and work of one of the greatest, if not the greatest, Queenslander, Sir Samuel Walker Griffith, a truly great Australian. 1 am doubly pleased to give this talk—first as a tribute to Clem Lack, with whom I was happy to work when I first came to Brisbane in 1936 as chief sub-editor of T/ie Courier-Mad. Then Clem Lack was writing his pungent political columns, writing from the press gallery of the Queensland Parliament with wit and erudition, in a style all his own. In this capacity he was following the subject of my talk, Sam Griffith, who broke into Queensland politics by the attention given to a series of articles he wrote about the Queensland Parliament, anonymously, when he was on vacation from studies at the Sydney University. Who am I talking about? The Right Honourable Sir Samuel Walker Griflhth, G.C.M.G., P.C, D.C.L., M.A. A man of quite extraordinary vision. He came to power as Premier for the first time in November, 1883. This was the session famous for ks Ten MiUion Loan. -

Samuel Walker Griffith: a Biographer and His Problems

Samuel Walker Griffith: A Biographer and his problems by the late Professor R.B. Joyce Presented at a Meeting of the Society 25 October 1984* I express my gratitude to the Royal Historical Society of Queens land for this opportunity of speaking, once again,' on Sir Samuel Walker Griffith. It is particularly fitting that I should be speaking in Brisbane for although Griffith was bom in Wales in 1845, this city was his adopted home. His parents who had migrated as zealous missionaries from Britain moved to Brisbane from Maitland in 1860. From then onwards Samuel spent most of his life in Brisbane. Even during his sixteen years as Chief Justice of Austraha (1903 to 1919) when he had to Uve in Sydney, then the centre of the High Court, he maintained his palatial home 'Merthyr' in New Farm, retuming to it as often as possible. When he finally retired, broken in health, he spent his last year in his beloved riverside home where he died on 9 August 1920. Griffith and Brisbane have been important to my life for a very long time. I first heard of the city through my mother's memories, of which more later; these went back to the 1880s. I wiU be retiring in a few months after 32 years of university teaching, 22 years of which were spent at Queensland University. It was here that I initially became interested in trying to understand Griffith, although I knew of him before. The prime acquaintance was with his judgements while I was studying law at Sydney University late in the 1940s. -

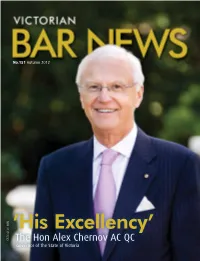

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 2

Proceedings of the Second Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two The Windsor Hotel, Melbourne; 30 July - 1 August 1993 Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Foreword (P4) John Stone Foreword Dinner Address (P5) The Hon. Jeff Kennett, MLA; Premier of Victoria The Crown and the States Introductory Remarks (P14) John Stone Introductory Chapter One (P15) Dr Frank Knopfelmacher The Crown in a Culturally Diverse Australia Chapter Two (P18) John Hirst The Republic and our British Heritage Chapter Three (P23) Jack Waterford Australia's Aborigines and Australian Civilization: Cultural Relativism in the 21st Century Chapter Four (P34) The Hon. Bill Hassell Mabo and Federalism: The Prospect of an Indigenous People's Treaty Chapter Five (P47) The Hon. Peter Connolly, CBE, QC Should Courts Determine Social Policy? Chapter Six (P58) S E K Hulme, AM, QC The High Court in Mabo Chapter Seven (P79) Professor Wolfgang Kasper Making Federalism Flourish Chapter Eight (P84) The Rt. Hon. Sir Harry Gibbs, GCMG, AC, KBE The Threat to Federalism Chapter Nine (P88) Dr Colin Howard Australia's Diminishing Sovereignty Chapter Ten (P94) The Hon. Peter Durack, QC What is to be Done? Chapter Eleven (P99) John Paul The 1944 Referendum Appendix I (P113) Contributors Appendix II (P116) The Society's Statement of Purposes Published 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society P O Box 178, East Melbourne Victoria 3002 Printed by: McPherson's Printing Pty Ltd 5 Dunlop Rd, Mulgrave, Vic 3170 National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two ISBN 0 646 15439 7 Foreword John Stone Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society.