2 ".25 3:.M 2% Emmi :55 25.1 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Qualitative Meta-Analysis of State

The State of the State : A Qualitative Meta-Analysis of State Involvement in Television Broadcasting in the Former Czechoslovakia By Jonathan Andrew Stewart Honig A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Media and Communication Middle Tennessee State University August 2017 Thesis Committee : Chair Dr. Jan Quarles Dr. Larry Burriss Dr. Gregory G. Pitts ii For my family. Related or not, with us or gone. ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my Mother, Kathryn Lynn Stewart Honig, for all her tireless dedication and patience in helping me get to this point in my life. This would not be possible without the love and support of my friends and family, it would literally take multiple pages to thank you all. You know who you are. I would like to thank Dr. Jan Quarles for her support and leadership as a wonderful chair of my committee. I also want to express my gratitude to Dr. Larry Burriss and Dr. Gregory G. Pitts for forming the rest of my excellent committee, as well as to Dr. Jane Marcellus and Dr. Sanjay Asthana for their advice and support throughout the years. I would not be at this point in my life without you all. iii iv ABSTRACT With the collapse of Communism in Europe, the geopolitical terrain of the east and central portion of the continent was redrawn according to the changes caused by the implosion of the Warsaw Pact. Czechoslovakia is unique in that this change actually resulted in the vivisection of the nation into two separate countries, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. -

Media Influence Matrix Slovakia

J A N U A R Y 2 0 2 0 MEDIA INFLUENCE MATRIX: SLOVAKIA Government, Politics and Regulation Author: Marius Dragomir 2nd updated edition Published by CEU Center for Media, Data and Society (CMDS), Budapest, 2020 About CMDS About the author The Center for Media, Data and Society Marius Dragomir is the Director of the Center (CMDS) is a research center for the study of for Media, Data and Society. He previously media, communication, and information worked for the Open Society Foundations (OSF) policy and its impact on society and for over a decade. Since 2007, he has managed practice. Founded in 2004 as the Center for the research and policy portfolio of the Program Media and Communication Studies, CMDS on Independent Journalism (PIJ), formerly the is part of Central European University’s Network Media Program (NMP), in London. He School of Public Policy and serves as a focal has also been one of the main editors for PIJ's point for an international network of flagship research and advocacy project, Mapping acclaimed scholars, research institutions Digital Media, which covered 56 countries and activists. worldwide, and he was the main writer and editor of OSF’s Television Across Europe, a comparative study of broadcast policies in 20 European countries. CMDS ADVISORY BOARD Clara-Luz Álvarez Floriana Fossato Ellen Hume Monroe Price Anya Schiffrin Stefaan G. Verhulst Hungary, 1051 Budapest, Nador u. 9. Tel: +36 1 327 3000 / 2609 Fax: +36 1 235 6168 E-mail: [email protected] ABOUT THE MEDIA INFLUENCE MATRIX The Media Influence Matrix Project is run collaboratively by the Media & Power Research Consortium, which consists of local as well as regional and international organizations. -

Download the Full Journal Here

Editorial Board Editor-In-Chief Norbert Vrabec Deputy Managing Editor Monika Prostináková Hossová Indexing Process and Technical Editor Marija Hekelj Technical Editor and Distribution Ľubica Bôtošová Proofreading Team and English Editors František Rigo, Michal Valek, Sláva Gracová Photo Editors Kristián Pribila Grafic Production Coordinator Martin Graca Web Editor Andrej Brník Editorial Team Ľudmila Čábyová, Viera Kačinová, Slavomír Gálik, Martin Solík, Oľga Škvareninová, Denisa Jánošová Advisory Board Piermarco Aroldi (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milano, Italy) Alexander Fedorov (Russian Association for Film and Media Education, Russia) Jan Jirák (Metropolitan University Prague, Czech Republic) Igor Kanižaj (University of Zagreb, Croatia) Miguel Vicente Mariño (University of Valladolid, Spain) Radek Mezulánik (Jan Amos Komenský University in Prague, Czech Republic) Stefan Michael Newerkla (University of Vienna, Austria) Gabriel Paľa (University of Prešov, Slovak Republic) Veronika Pelle (Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary) Hana Pravdová (University of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, Slovak Republic) Charo Sádaba (University of Navarra in Pamplona, Spain) Lucia Spálová (Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Slovakia) Anna Stolińska (Pedagogical University of Kraków, Poland) Zbigniew Widera (University of Economics in Katowice, Poland) Markéta Zezulkova (Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic) Yao Zheng (Zhejiang University of Media and Communications, China) About the Journal Media Literacy and Academic -

Watching Socialist Television Serials in the 70S and 80S in the Former Czechoslovakia: a Study in the History of Meaning-Making1

Watching socialist television serials in the 70s and 80s 299 Watching socialist television serials in the 70s and 80s in the former Czechoslovakia: A study in the history of meaning-making1 Irena Reifová Abstract The aim of this chapter is to map out and analyze how the viewers of the communist-governed Czechoslovak television understood the propagandist television serials during so-called “normalization”, the last two decades of the communist party rule after the Prague Spring. It strives to show peculiarities of the research on television viewers’ capabilities to remember the meanings and details of hermeneutic agency which took place in the past. The role of reproductive memory in remembering the viewers’ experience buried under the grand socio-political switchover is also illuminated and used to coin the concept of “memory over dislocation”. Keywords: popular culture, television serials, Czechoslovak normalization, life-story research, collective memory, post-socialism Reifová, I. (2016) ‘Watching socialist television serials in the 70s and 80s in the former Czecho- slovakia: a study in the history of meaning-making’, pp. 297-309 in L. Kramp/N. Carpentier/A. Hepp/R. Kilborn/R. Kunelius/H. Nieminen/T. Olsson/P. Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt/I. Tomanić Tri- vundža/S. Tosoni (Eds.) Politics, Civil Society and Participation: Media and Communications in a Transforming Environment. Bremen: edition lumière. 1 This chapter is a shortened version of the article “Watching socialist television serials in the 70s and 80s in the former Czechoslovakia: a study in the history of meaning-making” pub- lished in European Journal of Communication, 30(1). 300 Irena Reifová 1 Introduction This chapter seeks to challenge a tacit assumption that instrumental and in- terpretive autonomy of media use can only be looked for in the democratic environment. -

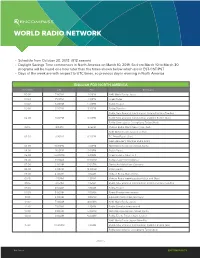

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

Review: KE007 a Conspiracy of Circumstance, by Murray Sayle

Review: KE007 A Conspiracy of Circumstance, By Murray Sayle The New York Review of Books // April 25, 1985 Black Box: KAL 007 and the Superpowers, by Alexander Dallin // University of California Press, 130 pp., $7.95 (paper) KAL Flight 007: The Hidden Story, by Oliver Clubb // Permanent Press, 174 pp., $16.95 Final Report of Investigation as Required in the Council Resolution of September 16, 1983 [C-WP/7764] International Civil Aviation Organization (Montreal), 113, restricted, but available on serious request pp. 1818th Report to Council by the President of the Air Navigation Commission [C-WP/7809] International Civil Aviation Organization (Montreal), 23, restricted, but available on serious request pp. North Atlantic Airspace Operations Manual-Fourth Edition Civil Aviation Authority (London), 32, available on request pp. NOPAC Route Systems Operations Handbook Administration Anchorage Air Route Traffic Control Center, Federal Aviation, 16, available on request pp. 1. Shortly before dawn on September 1, 1983, a Boeing 747 Flight KE007 of Korean Air Lines was shot down over Sakhalin Island in the Soviet Far East by an SU-15 fighter of the Soviet Air Force, with the loss of all 269 passengers and crew on board. The incident set off a contest in vituperation between the super-powers, which, a year and a half later, still reverberates. President Reagan called the shoot-down "a terrorist act to sacrifice the lives of innocent human beings," while the Soviets have never ceased charging that the aircraft was engaged on a "special mission" of electronic espionage on behalf of the United States, thus by implication justifying what they call their "termination" of the flight. -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

Welcome Guide for Researchers Getting Started in Dresden‘S Research Landscape

WELCOME GUIDE FOR RESEARCHERS Getting started in Dresden‘s research landscape 1 INDEX Rector´s statement..................................................................................4 Before arrival Visa and entry..........................................................................................5 Travel health insurance and important documents..............................6 Family After arrival Dual Career Service ...................................................................30 Local registration .....................................................................................8 Childcare.................................................................................... 31 Residence and work permit .......................................................................9 School system........................................................................... 33 Funding...........................................................................................................10 School registration..................................................................... 34 Social security system.............................................................................12 Benefits for families...................................................................35 Health insurance.....................................................................................13 Having a baby............................................................................. 37 General information on housing................................................................14 -

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 CATALOGUE 2018 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 CATALOGUE 2018 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany WORLD SALES CEO: Jan Mojto C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. [email protected] Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet [email protected] [email protected] ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES AVAILABLE FOR THE FIRST TIME FOR GLOBAL DISTRIBUTION LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

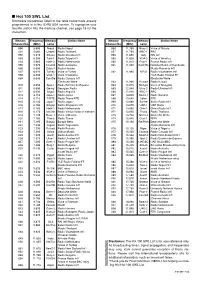

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Jim's 1985 Book Reviews Debunk the Conspiracies

An abridged version of the following review appeared in ‘The American Spectator’, October 1985, pp 36-39. The second review is from ’National Review’ magazine, March 27, 1987. Sense, Nonsense, and Pretense on the Korean Airliner Atrocitv -- A Reader's Guide to the Literature, by James E. Oberg // date: July 31, 1985 "Reassessing the Sakhalin incident“, P. Q. Mann (pseudonym). Defence Attache, No. 3. (May-June) 1984, pp 41-56. "K.A.L. 007: What the U.S. Knew and When We Knew It", David Pearson. The Nation, Aug 18-25, 1984, pp 105-124. "Sakhalin Sense and Nonsense", J. E. Oberg, Defence Attache, No. 1 (Jan-Feb) 1985. pp 37-47. KAL FLIGHT 007: The Hidden Story, by Oliver Clubb, Permanent Press, Sag Harbor, New York, April 1965, 174 pages, $16.95. Black Box: KAL 007 and the Superpowers. by Alexander Dallin. University of California Press, Berkeley. California. 1985, 130 pages, $14.95. Day of the Cobra The True Story of KAL Flight 007, by Jeffrey St. John, Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville, Tennessee, 1984, 254 pages, $11.95. Massacre 747: The Story of Korean Airlines Flight 007, by Richard Rohmer, Paperjacks Ltd., Markham, Ontario. May 1964, 213 pages paperback, $3.95. The Curious Flight, of KAL 007, by Conn Hallinan, U. S. Peace Council, New York, NY, 1984, 6 pages. The President's Crime: The Provocation with the South Korean Airliner Carried Out by Order of Reagan, by "Akio Takahashi", Novosti Publishers,Moscow, 1984, 126 pages, 30 kopecks. "KE007 -- A Conspiracy of Circumstance", Murray Sayle, The New York Review of Books, April 25, 1965, pages 44-54. -

An Analysis of the Czechoslovak Media Following the Act of Jan Palach’S Self-Immolation

Master of Arts Thesis Euroculture Palacky University in Olomouc, Czech Republic Georg-August University in Göttingen, Germany May 2014 An Analysis of the Czechoslovak Media Following the Act of Jan Palach’s Self-immolation Submitted by: Mariana Olšarová Student number home university: F12056 Student number host university: 11332047 [email protected] Supervised by: PhDr. Petr Blažek, Ph.D. Prof. Dr. Petra Terhoeven Göttingen, 28. 5. 2014 Signature 1 MA Programme Euroculture Declaration I, Mariana Olšarová hereby declare that this thesis, entitled “An Analysis of the Czechoslovak Media Following the Act of Jan Palach’s Self-immolation”, submitted as partial requirement for the MA Programme Euroculture, is my own original work and expressed in my own words. Any use made within this text of works of other authors in any form (e.g. ideas, figures, texts, tables, etc.) are properly acknowledged in the text as well as in the bibliography. I hereby also acknowledge that I was informed about the regulations pertaining to the assessment of the MA thesis Euroculture and about the general completion rules for the Master of Arts Programme Euroculture. Signed ………………………………….. Date 28. 5 2014 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................. 3 Preface .............................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................... 8 1.1 General Introduction ..............................................................................................