Slovakia Chapter.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data Specification on Administrative Units – Guidelines

INSPIRE Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe D2.8.I.4 INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units – Guidelines Title D2.8.I.4 INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units – Guidelines Creator INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Date 2009-09-07 Subject INSPIRE Data Specification for the spatial data theme Administrative units Publisher INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Type Text Description This document describes the INSPIRE Data Specification for the theme Administrative units Contributor Members of the INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Format Portable Document Format (pdf) Source Rights public Identifier INSPIRE_DataSpecification_AU_v3.0.pdf Language En Relation Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE) Coverage Project duration INSPIRE Reference: INSPIRE_DataSpecification_AU_v3.0.docpdf TWG-AU Data Specification on Administrative units 2009-09-07 Page II Foreword How to read the document? This guideline describes the INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units as developed by the Thematic Working Group Administrative units using both natural and a conceptual schema languages. The data specification is based on the agreed common INSPIRE data specification template. The guideline contains detailed technical documentation of the data specification highlighting the mandatory and the recommended elements related to the implementation of INSPIRE. The technical provisions and the underlying concepts are often illustrated by examples. Smaller examples are within the text of the specification, while longer explanatory examples are attached in the annexes. The technical details are expected to be of prime interest to those organisations that are/will be responsible for implementing INSPIRE within the field of Administrative units. -

Czech and Slovak

LETTER-WRITING GUIDE Czech and Slovak INTRODUCTION Republic, the library has vital records from only a few German-speaking communities. Use the This guide is for researchers who do not speak Family History Library Catalog to determine what Czech or Slovak but must write to the Czech records are available through the Family History Republic or Slovakia (two countries formerly Library and the Family History Centers. If united as Czechoslovakia) for genealogical records are available from the library, it is usually records. It includes a form for requesting faster and more productive to search these first. genealogical records. If the records you want are not available through The Republic of Czechoslovakia was created in the Family History Library, you can use this guide 1918 from parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. to help you write to an archive to obtain From Austria it included the Czech provinces of information. Bohemia, Moravia, and most of Austrian Silesia. From Hungary it included the northern area, which BEFORE YOU WRITE was inhabited primarily by Slovaks. The original union also included the northeastern corner of Before you write a letter to the Czech Republic or Hungary, which was inhabited mainly by Slovakia to obtain family history information, you Ukrainians (also called Ruthenians), but this area, should do three things: called Sub-Carpathian Russia, was ceded to the Soviet Republic of Ukraine in 1945. Since 1993, C Determine exactly where your ancestor was the Czech Republic and Slovakia have been two born, was married, resided, or died. Because independent republics with their own governments. most genealogical records were kept locally, you will need to know the specific locality where your ancestor was born, was married, resided for a given time, or died. -

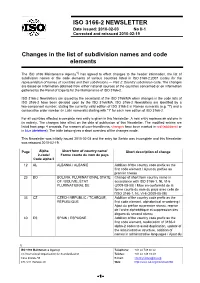

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Administrace Okres Kraj Územní Oblast Abertamy Karlovy Vary Karlovarský Kraj Plzeň Adamov Blansko Jihomoravský Kraj Brno Ad

Administrace Okres Kraj Územní oblast Abertamy Karlovy Vary Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Adamov Blansko Jihomoravský kraj Brno Adamov České Budějovice Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Adamov Kutná Hora Středočeský kraj Trutnov Adršpach Náchod Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtice Karviná Moravskoslezský kraj Ostrava Albrechtice Ústí nad Orlicí Pardubický kraj Jeseník Albrechtice nad Orlicí Rychnov nad Kněžnou Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtice nad Vltavou Písek Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Albrechtice v Jizerských horách Jablonec nad Nisou Liberecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtičky Nový Jičín Moravskoslezský kraj Ostrava Alojzov Prostějov Olomoucký kraj Brno Andělská Hora Bruntál Moravskoslezský kraj Jeseník Andělská Hora Karlovy Vary Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Anenská Studánka Ústí nad Orlicí Pardubický kraj Jeseník Archlebov Hodonín Jihomoravský kraj Brno Arneštovice Pelhřimov Vysočina Jihlava Arnolec Jihlava Vysočina Jihlava Arnoltice Děčín Ústecký kraj Ústí nad Labem Aš Cheb Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Babice Hradec Králové Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Babice Olomouc Olomoucký kraj Jeseník Babice Praha-východ Středočeský kraj Praha Babice Prachatice Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Babice Třebíč Vysočina Jihlava Babice Uherské Hradiště Zlínský kraj Zlín Babice nad Svitavou Brno-venkov Jihomoravský kraj Brno Babice u Rosic Brno-venkov Jihomoravský kraj Brno Babylon Domažlice Plzeňský kraj Plzeň Bácovice Pelhřimov Vysočina Jihlava Bačalky Jičín Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Bačetín Rychnov nad Kněžnou Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Bačice Třebíč Vysočina -

The Evolution of the Party Systems of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic After the Disintegration of Czechoslovakia

DOI : 10.14746/pp.2017.22.4.10 Krzysztof KOŹBIAŁ Jagiellonian University in Crakow The evolution of the party systems of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic after the disintegration of Czechoslovakia. Comparative analysis Abstract: After the breaking the monopoly of the Communist Party’s a formation of two independent systems – the Czech and Slovakian – has began in this still joint country. The specificity of the party scene in the Czech Republic is reflected by the strength of the Communist Party. The specificity in Slovakia is support for extreme parties, especially among the youngest voters. In Slovakia a multi-party system has been established with one dominant party (HZDS, Smer later). In the Czech Republic former two-block system (1996–2013) was undergone fragmentation after the election in 2013. Comparing the party systems of the two countries one should emphasize the roles played by the leaders of the different groups, in Slovakia shows clearly distinguishing features, as both V. Mečiar and R. Fico, in Czech Republic only V. Klaus. Key words: Czech Republic, Slovakia, party system, desintegration of Czechoslovakia he break-up of Czechoslovakia, and the emergence of two independent states: the TCzech Republic and the Slovak Republic, meant the need for the formation of the political systems of the new republics. The party systems constituted a consequential part of the new systems. The development of these political systems was characterized by both similarities and differences, primarily due to all the internal factors. The author’s hypothesis is that firstly, the existence of the Hungarian minority within the framework of the Slovak Republic significantly determined the development of the party system in the country, while the factors of this kind do not occur in the Czech Re- public. -

Data on Urban and Rural Population in Recent Censusespdf

. ~ . DATA ON URBAN AND RURAL POPULA'EION . IN RECENT CENSUSES ... I UNITED NATIONS POPULATION STUDIES, No. 8 D_ATA ON URBAN AND RURAL POPULATION IN RECENT CENSUSES Department of Social Affairs Department of Economic Affairs Population Division Statistical Office of the United Nations Lake Success, New York July 1950 .... ST/ SOA/Series A. Population Studies, No. 8 List of reports in this series to date : Reports on the Population of Trust Territories No. 1. The Population of W estem Samoa No. 2. The Population of Tanganyika Reports on Popub.tion Estimates No. 3. World Population Trends, 1920-1947 Reports on Methods of Population St:atist.ics No. 4. Population Census Methods No. 6. Fertility Data in Population Censuses No. 7. Methods of Using Census Statistics for the Calculation or Life Tables and Other Demographic Measures. With Application to the Population of Brazil. By Giorgio Mortara No. 8. Data on Urban and Rural Population in Recent Censuses Report• on Demographic Aspects of Mi.gration No. 5. Problems of Migration Statistics UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATIONS S:ales No.: 1950 • Xlll • 4 · ~ FOREWORD The Economic and Social Council, at its fourth session, adopted a resolution requesting the Secretary-General of the United Nations to offer advice and assist ance to Member States, with a view to improving the comparability and quality of data to be obtained in the censuses of 1950 and proximate years (resolution 41 (IV), 29 March 1947). As part of the implementation of this resolution, a series of studies has been prepared on the methods of obtaining and presenting information in population censuses on the size and characteristics of the population. -

Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2003/1 The Szlonzoks and their Language: Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism TOMASZ KAMUSELLA BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author(s). © 2003 Tomasz Kamusella Printed in Italy in December 2003 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico (FI) Italy ________Tomasz Kamusella________ The Szlonzoks1 and Their Language: Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism Tomasz Kamusella Jean Monnet Fellow, Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence, Italy & Opole University, Opole, Poland Please send any comments at my home address: Pikna 3/2 47-220 Kdzierzyn-Koïle Poland [email protected] 1 This word is spelt in accordance with the rules of the Polish orthography and, thus, should be pronounced as /shlohnzohks/. 1 ________Tomasz Kamusella________ Abstract This article analyzes the emergence of the Szlonzokian ethnic group or proto- nation in the context of the use of language as an instrument of nationalism in Central Europe. When language was legislated into the statistical measure of nationality in the second half of the nineteenth century, Berlin pressured the Slavophone Catholic peasant-cum-worker population of Upper Silesia to become ‘proper Germans’, this is, German-speaking and Protestant. To the German ennationalizing2 pressure the Polish equivalent was added after the division of Upper Silesia between Poland and Germany in 1922. The borders and ennationalizing policies changed in 1939 when the entire region was reincorporated into wartime Germany, and, again, in 1945 following the incorporation of Upper Silesia into postwar Poland. -

Pogrom Cries – Essays on Polish-Jewish History, 1939–1946

Rückenstärke cvr_eu: 39,0 mm Rückenstärke cvr_int: 34,9 mm Eastern European Culture, 12 Eastern European Culture, Politics and Societies 12 Politics and Societies 12 Joanna Tokarska-Bakir Joanna Tokarska-Bakir Pogrom Cries – Essays on Polish-Jewish History, 1939–1946 Pogrom Cries – Essays This book focuses on the fate of Polish “From page one to the very end, the book Tokarska-Bakir Joanna Jews and Polish-Jewish relations during is composed of original and novel texts, the Holocaust and its aftermath, in the which make an enormous contribution on Polish-Jewish History, ill-recognized era of Eastern-European to the knowledge of the Holocaust and its pogroms after the WW2. It is based on the aftermath. It brings a change in the Polish author’s own ethnographic research in reading of the Holocaust, and offers totally 1939–1946 those areas of Poland where the Holo- unknown perspectives.” caust machinery operated, as well as on Feliks Tych, Professor Emeritus at the the extensive archival query. The results Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw 2nd Revised Edition comprise the anthropological interviews with the members of the generation of Holocaust witnesses and the results of her own extensive archive research in the Pol- The Author ish Institute for National Remembrance Joanna Tokarska-Bakir is a cultural (IPN). anthropologist and Professor at the Institute of Slavic Studies of the Polish “[This book] is at times shocking; however, Academy of Sciences at Warsaw, Poland. it grips the reader’s attention from the first She specialises in the anthropology of to the last page. It is a remarkable work, set violence and is the author, among others, to become a classic among the publica- of a monograph on blood libel in Euro- tions in this field.” pean perspective and a monograph on Jerzy Jedlicki, Professor Emeritus at the the Kielce pogrom. -

![Arxiv:1804.02448V1 [Math.HO] 6 Apr 2018 OIHMTEAIIN N AHMTC in MATHEMATICS and MATHEMATICIANS POLISH E Od N Phrases](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6946/arxiv-1804-02448v1-math-ho-6-apr-2018-oihmteaiin-n-ahmtc-in-mathematics-and-mathematicians-polish-e-od-n-phrases-3166946.webp)

Arxiv:1804.02448V1 [Math.HO] 6 Apr 2018 OIHMTEAIIN N AHMTC in MATHEMATICS and MATHEMATICIANS POLISH E Od N Phrases

POLISH MATHEMATICIANS AND MATHEMATICS IN WORLD WAR I STANISLAW DOMORADZKI AND MALGORZATA STAWISKA Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Galicja 7 2.1. Krak´ow 7 2.2. Lw´ow 14 3. The Russian empire 20 3.1. Warsaw 20 3.2. St. Petersburg (Petrograd) 28 3.3. Moscow 29 3.4. Kharkov 32 3.5. Kiev 33 3.6. Yuryev(Dorpat;Tartu) 36 4. Poles in other countries 37 References 40 Abstract. In this article we present diverse experiences of Pol- ish mathematicians (in a broad sense) who during World War I fought for freedom of their homeland or conducted their research and teaching in difficult wartime circumstances. We first focus on those affiliated with Polish institutions of higher education: the ex- isting Universities in Lw´ow in Krak´ow and the Lw´ow Polytechnics arXiv:1804.02448v1 [math.HO] 6 Apr 2018 (Austro-Hungarian empire) as well as the reactivated University of Warsaw and the new Warsaw Polytechnics (the Polish Kingdom, formerly in the Russian empire). Then we consider the situations of Polish mathematicians in the Russian empire and other coun- tries. We discuss not only individual fates, but also organizational efforts of many kinds (teaching at the academic level outside tradi- tional institutions– in Society for Scientific Courses in Warsaw and in Polish University College in Kiev; scientific societies in Krak´ow, Lw´ow, Moscow and Kiev; publishing activities) in order to illus- trate the formation of modern Polish mathematical community. Date: April 10, 2018. 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. 01A60; 01A70, 01A73, 01A74. Key words and phrases. Polish mathematical community, World War I. -

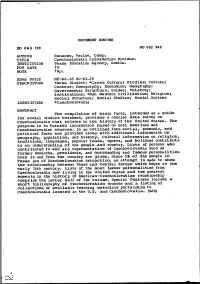

For Social Etudies Teachers, Provides a Concise Data Survey On

DOCUMENT RES'JME ED 063 199 SO 002 948 AUTHOR Hunacek, Vac lav, Comp. TITLE Czechoslovakia Inf ormation Minimum. INSTITUTION Texas Education Agency, Austin. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 78p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Area Studies; *Cross Cultural Studies;Cultural Context; Demography; Economics; Geography; Governmental Structure; Guides; *History; Institutions; *Non Western Civilization;Religion; Social Structure; Social Studies; Social Systems IDENT IF IERS *Czechoslovakia ABSTRACT The compilation of basic facts, intended as aguide for social Etudies teachers, provides aconcise data survey on Czechoslovakia that relates to the history of theUnited States. The purpose is to furnish informationbased on both American and Czechoslovakian sources. In an outlined form social,economic, and political facts are provided along with additionalinformation on geography, copulation, and history. Culturalinformation on religion, traditions, languages, popular foods, sports, andholidays contribute to an understanding of the people and country.Lists of persons who contributed to and are representative ofCzechoslovakia such as former monarchs, presidents, and outstanding andfamous personalities born in and from the country are given. Since 5%of the people in Texas are of Czechoslovakian extraction, anattempt is made to show the relationship between Texas and Central Europewhich began in the early 16th century. Lists of the most famouspersonalities from Czechoslovakia now living in the United States and tengreatest moments in the history of American-Czechoslovakianrelationship comprise the latter half of the volume. Specialfeatures include a short bibliography of Czechoslovakian sources and alisting of collections of available teaching materialspertaining to Czechoslovakia located in the U.S. and Czechoslovakia. (SJM) rt, .: 4 - 1 !'\.t 1 5. -

Czech Repulbic 96

I. GENERAL INFORMATION I. GENERAL INFORMATION I.1 History The first signs of people living in what army and incorporated as a special auto- is today the Czech Republic are as old as nomous state into the German Empire. In 1.6 - 1.7 million years and were found ne- 1945, Czechoslovakia was liberated by ar Beroun in Central Bohemia. The first the Soviet and American armies. The Cze- Slavonic people came in the 5th and 6th choslovak state was restored without centuries. The first written references to Carpatho-Russia which joined the Soviet the Czechs, Prague, and regions of Bohe- Union. mia appeared in the 8th and 9th centu- In February 1948, the Communist ries. In about the year 870, the Czech party gained power (in a formal constitu- prince Borivoj was mentioned for the first tional way), and Czechoslovakia was under time. He came from Prague and belonged Soviet influence until 1989. After the to the House of Premysl, which later be- „Velvet Revolution“ in 1989, the democra- came the royal dynasty of Bohemia. This tic regime was restored. dynasty governed the Czech kingdom In response to the Slovak desire for until 1306. During the reign of the House greater self determination, a federal con- of Luxembourg (1310-1436), Bohemia stitution was introduced in 1968. Com- was the center of the so-called Holy West pletely controlled by the Communist Par- Roman Empire of German People and ty, the Czechoslovak Federation had not Prague became one of the cultural centers satisfied the legitimate aspirations of the of Europe. -

1 Germanization, Polonization and Russification in the Partitioned

Germanization, Polonization and Russification in the Partitioned Lands of Poland-Lithuania: Myths and Reality1 Tomasz Kamusella Trinity College Dublin Abstract Two main myths constitute the founding basis of popular Polish ethnic nationalism. First, that Poland-Lithuania was an early Poland, and second, that the partitioning powers at all times unwaveringly pursued policies of Germanization and Russification. In the former case, the myth appropriates a common past today shared by Belarus, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine. In the latter case, Polonization is written out of the picture entirely, as also are variations and changes in the polices of Germanization and Russification. Taken together, the two myths to a large degree obscure (and even falsify) the past, making comprehension of it difficult, if not impossible. This article seeks to disentangle the knots of anachronisms that underlie the Polish national master narrative, in order to present a clearer picture of the interplay between the policies of Germanization, Polonization and Russification as they unfolded in the lands of the partitioned Poland- Lithuania during the long 19th century. Key words: Germanization, nationalism, partitioned lands of Poland- Lithuania, Poland-Lithuania, Polonization, Russification Introduction Between 2007 and 2010, I taught Irish students who, in the framework of their European studies track, specialized in Polish language and culture in Trinity College, Dublin. In the third year of their studies they went to Poland to attend Polish-language courses at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow. On their return to Ireland for the final year of their studies, I lectured to them on the partitioned lands of the Commonwealth of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the long 19th century.