A Study of the Histories and Inspirations Behind Selections of Songs from the Soprano Repertoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Annotated Listing of Mozart's Smaller , Sacred Choral Works

An Annotated Listing of Mozart's Smaller , Sacred Choral Works by David Rayl s we approach the 200th Editions anniversary of the death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Obviously, no two editions of the choral conductors are same work are identical; some are beginning to consider carefully edited according to scholarly Aprograms which will suitably criteria while others are poorly edited commemorate the death of this most and misrepresent the original score. amazing of composers. There will Carus-Verlag, whose publications are undoubtably be many performances of available through Mark Foster, has his Requiem and the C minor Mass, begun to publish editions of much of as well as the better-mown works Mozart's choral music. Their excellent from his tenure in Salzburg, such as editions are generally the best the "Coronation" Mass and the available, being based on the Neue Solemn Vespers of a Confessor. But Mozart Ausgabe. Each contains an there are many smaller choral works excellent forward with information which are unjustly neglected and about the origin of the work, the which deserve more frequent manuscript sources used in its performance. Most of these are not so English.) This list includes a variety of preparation, a translation of the text, difficult as to restrict their genres: six offertories (K. 34, and some ideas about appropriate performance to college! university K. 117/66a, K. 72/74f, K. 222/205b, performance practice. The problem choirs; they are eminently accessible to K. 260/248a, K. 277/272a), three with these editions is that not all the a great many high school and church Regina coeli settings (K. -

The Skirmisher

THE SKIRMISHER CIVIL WAR TRUST THE STORM AFTER THE CALM: 1861 VOLUME 5 THINGS FALL APART The new year of 1861 opened with secession weighing heavily on the American mind. Citing abuses of constitutional law, plans for the abolition of slavery, and a rigged 1860 presidential election, the state of South Carolina had dissolved its bonds with the Union less than two weeks before. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana left by the end of January, seizing a number of Federal arsenals as they went. Northerners were agog at the rapid turn of events. Abraham Lincoln refused to surrender Federal forts in Confederate territory, but their garrisons would starve without fresh provisions. The new president, only 60 days into his first term, sent the steamer Star of the West to resupply Fort Sumter in the Charleston, South Carolina harbor. Charleston’s cannons opened fire on the ship, turning it away at the mouth of the harbor. The brief salvo showed the depth of feeling in the Rebel states. Texas left the Union, even though Texas governor Sam Houston refused to take the secession oath, telling his citizens South Carolina seceded from the Union with that “you may, after a sacrifice of countless millions of treasures and hundreds of thousands great fanfare. (Library of precious lives, as a bare possibility, win Southern independence…but I doubt it.” of Congress) In February, the newly-named Confederate States of America held its first constitutional convention. The Confederate States Army took shape, and quickly forbade any further resupplies of Federal forts. The Fort Sumter garrison was very low on food. -

COPPÉLIA.Pdf

ALBO DEI FONDATORI CONSIGLIO DI AMMINISTRAZIONE Giorgio Orsoni presidente Stato Italiano Luigino Rossi vicepresidente Fabio Cerchiai SOCI SOSTENITORI Jas Gawronski Achille Rosario Grasso Luciano Pomoni Giampaolo Vianello Francesca Zaccariotto Gigliola Zecchi Balsamo consiglieri SOCI BENEMERITI sovrintendente Giampaolo Vianello direttore artistico Fortunato Ortombina COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI DEI CONTI Giancarlo Giordano, presidente Giampietro Brunello Adriano Olivetti Andreina Zelli, supplente SOCIETÀ DI REVISIONE PricewaterhouseCoopers S.p.A. ALBO DEI FONDATORI COPPÉLIA SOCI ORDINARI ballet pantomime in due atti soggetto di Charles Jude da Arthur Saint-Léon e Charles Nuitter coreografia di Charles Jude musica di Léo Delibes Teatro La Fenice mercoledì 21 luglio 2010 ore 19.00 turno A giovedì 22 luglio 2010 ore 19.00 turno E venerdì 23 luglio 2010 ore 19.00 turno D sabato 24 luglio 2010 ore 15.30 turno C domenica 25 luglio 2010 ore 15.30 turno B Stagione 2010 Lirica e Balletto Stagione 2010 Lirica e Balletto Sommario 4 La locandina 9 Un balletto boulevardier di Silvia Poletti 15 Coppélia in breve 17 Argomento - Argument - Synopsis - Handlung 23 Dall’archivio storico del Teatro La Fenice Le bambole meccaniche di E.T.A. Hoffmann al Teatro La Fenice 29 Biografie Léo Delibes, autore della musica di Coppélia, in un disegno (c. 1880) di Louise Abbéma (1853-1927). Clément Philibert Léo Delibes (1836-1891) studiò composizione al Conservatorio di Parigi con Adolphe Adam. Scrisse varie operette, i balletti La source, Coppélia e Sylvie e le opere Jean -

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas R. Bell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Dr. Sabine Wilke, Chair Dr. Richard Block Dr. Eric Ames Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2015 Thomas R. Bell University of Washington Abstract The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas Richard Bell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Sabine Wilke Germanics This dissertation focuses on texts written by four contemporary, German-speaking authors: W. G. Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn and Schwindel. Gefühle, Daniel Kehlmann’s Die Vermessung der Welt, Sybille Lewitscharoff’s Blumenberg, and Peter Handke’s Der Große Fall. The project explores how the texts represent forms of religion in an increasingly secular society. Religious themes, while never disappearing, have recently been reactivated in the context of the secular age. This current societal milieu of secularism, as delineated by Charles Taylor, provides the framework in which these fictional texts, when manifesting religious intuitions, offer a postsecular perspective that serves as an alternative mode of thought. The project asks how contemporary literature, as it participates in the construction of secular dialogue, generates moments of religiously coded transcendence. What textual and narrative techniques serve to convey new ways of perceiving and experiencing transcendence within the immanence felt and emphasized in the modern moment? While observing what the textual strategies do to evoke religious presence, the dissertation also looks at the type of religious discourse produced within the texts. The project begins with the assertion that a historically antecedent model of religion – namely, Friedrich Schleiermacher’s – which is never mentioned explicitly but implicitly present throughout, informs the style of religious discourse. -

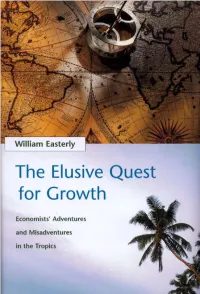

William Easterly's the Elusive Quest for Growth

The Elusive Quest for Growth Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics William Easterly The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 0 2001 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. Lyrics from ”God Bless the Child,” Arthur Herzog, Jr., Billie Holiday 0 1941, Edward B. Marks Music Company.Copyright renewed. Used by permission. All rights reserved. This book was set in Palatino by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong, in ’3B2’ Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Easterly, William. The elusive quest for growth :economists’ adventures and misadventures in the tropics /William Easterly. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-05065-X (hc. :alk. paper) 1. Poor-Developing countries. 2. Poverty-Developing countries. 3. Developing countries-Economic policy. I. Title. HC59.72.P6 E172001 338.9’009172’4-dc21 00-068382 To Debbie, Rachel, Caleb, and Grace This Page Intentionally Left Blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Prologue: The Quest xi I Why Growth Matters 1 1 To Help the Poor 5 Intermezzo: In Search of a River 16 I1 Panaceas That Failed 21 2 Aid for Investment 25 Zntermezzo: Parmila 45 3 Solow’s Surprise: Investment Is Not the Key to Growth 47 Intermezzo: DryCornstalks 70 4 Educated for What? 71 Intermezzo: Withouta -

Life of Mozart, Vol. 1

Life Of Mozart, Vol. 1 By Otto Jahn LIFE OF MOZART. CHAPTER I. — CHILDHOOD WOLFGANG AMADE MOZART came of a family belonging originally to the artisan class. We find his ancestors settled in Augsburg early in the seventeenth century, and following their calling there without any great success. His grandfather, Johann Georg Mozart, a bookbinder, married, October 7, 1708, Anna Maria Peterin, the widow of another bookbinder, Augustin Banneger. From this union sprang two daughters and three sons, viz.: Fr. Joseph Ignaz, Franz Alois (who carried on his father's trade in his native town), and Johann Georg Leopold Mozart, bom on November 14, 1719, the father of the Mozart of our biography. Gifted with a keen intellect and firm will he early formed the resolution of raising himself to a higher position in the world than that hitherto occupied by his family; and in his later years he could point with just elation to his own arduous efforts, and the success which had crowned them, when he was urging his son to the same steady perseverance. When Wolfgang visited Augsburg in 1777, he gathered many particulars of his father's youth which refreshed the recollections of Leopold himself. We find him writing to his son (October 10, 1777) how, as a boy, he had sung a cantata at the monastery of St. Ulrich, for the wedding of the Hofrath Oefele, and how he had often climbed the broken steps to the organ loft, to sing treble at the Feast of the Holy Cross (November 29, 1777). He afterwards became an excellent organist: a certain Herr von Freisinger, of Munich, told Wolfgang (October 10, 1777) that he knew his father well, he had studied with him, and "had the liveliest recollections of Wessobrunn where my father (this was news to me) played the organ remarkably well. -

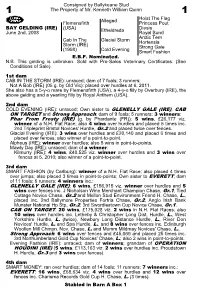

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

ED 110 544 Individualized Language Arts

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 110 544 88 UD 015 350 TITLE Individualized Language Arts--Diagnosis, Prescription, Evaluation. A Teacher's 'Resource Manual...ESEA Title III Project: 70-014. INSTITUTION Weehawken Board of Education, N.J. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 308p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$15.86 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Guides; *Diagnostic Teaching; Educational Diagnosis; Educational Resources; Elementary School Curriculum; Instructional Materials; *Language-Arts; Manuals; Secondary Education; *Teaching. Guides; Writing Exercises; *Writing Skills IDENTIFIERS *Elementary Secondary Education ActTite1 e III; ESEA Title III; New Jersey; Weehawken ABSTRACT l This document is a teachers' resource manual, grades Kindergarten through Twelve, for the promotion of students' facility in written composition in the context ofa language-experience approach and through the use of diagnostic-prescriptivetechniques derived from modern linguistic'theory. The "IndividualizedLanguage Arts: Diagnosis; Prescription, and Evaluation" project (on which this manual is based) was validated in 1973 by the standards and guidelines of the U.S. Office of Educationas innovative, successful, cost-effective, and exportable. As a result of the validation,the project is now funded as a demonstration site by the New Jersey ESEA Title III program. This Project, it is stated,was designed to meet the critical need of educators to developmore effective methods of analyzing students' writing, and to prescribe and apply individualized instructional techniques in order to promotegreater writing facility. The students' writing development is traced by three samples, taken at three intervals during theyear. The __evaluation of the samples, based on commonly acceptedLanguage Arts objectives is considered to pinpoint each student'scurrent strengths and needs. A prescriptive program which is said to emphasize the integration of subject areas is used inn this Project. -

Arriva Un Bastimento Carico Di Artisti. Sulle Tracce Della Cultura Italiana Nella Buenos Aires Del Centenario

RiMe Rivista dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Europa Mediterranea ISSN 2035-794X numero 6, giugno 2011 Arriva un bastimento carico di artisti. Sulle tracce della cultura italiana nella Buenos Aires del Centenario Irina Bajini Istituto di Storia dell’Europa Mediterranea Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche http://rime.to.cnr.it ! " # $ O P % & " ' ()% !! '* " " ! ' ) I ' % & * % & ,& " & ' - !! * - ' "." % ! " " 0 !! 0 % # &$ '--'-1' 1 1--) ' !! ' 'R' 3 M )'R ' 'R' *355-666 5 7 70 6)897:9:8;! !19::<=9>=?95?=;@7%A9::B:8;>@? &3 &6-C-66 '3 '6-C-66 ) ! "# $% &" ' $%!" '(" " " )% $%% &%! *% + , -# ' ". / " "" )#! %0 & ' &'"%% ' %" R" & '% !##" '+#" % %3! " 4 ##% " % "5' $# #!!. 6! %'7 ! %8 %! %' ' &! 5 ! )% " 7 ! % "% ' 0 9%" $ %% $ %" ' #"% %"%' ) % (% #(!! 7R%!.""" %' R& %0 " % " %3 7 "%" %& %" 3 %&!' ! !!! % " 7 => " *'& ' 4&!#( # O @ #' &"P % ! &%7%%#"0 ' R&& %0 " % "' % &0 %'3Q %&9% $% #"" "%!.!" ""%" %% "' #! %)@ %% 9#"&" !%! '%"#" "%!!' ! " % " ) #%#' ("% '! ! 7 C * "% ' # % # ' * % @ D!! ' 4 3 #!."" #9 !. M %&4 %#C & @%# #"# % & @%# " # + % "# %! #' # %(%#"F%'G !.#=9F *&%##+&%#% #" #' ("% ' % " "%#" ' '% " # % 3 # ) % 5 & " &#" #"% "%% ' #9'%"# $ " $ %0 ! '' + (" !#& * '#%% ' ' ' ! ! "K" ' % ' !! " !" ' -

Ernest Guiraud: a Biography and Catalogue of Works

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works. Daniel O. Weilbaecher Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Weilbaecher, Daniel O., "Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4959. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4959 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 35,1915-1916, Trip

SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY ^\^><i Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor ITTr WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 23 AT 8.00 COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 1 €$ Yes, It's a Steinway ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to I you. and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extra dollars and got a Steinway." pw=a I»3 ^a STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Violins. Witek, A. Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet. H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Sulzen, H. -

SUV Dept NL Summer 2009.Pub

SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR DEPARTMENT OF COLORADO / WYOMING Vol. 2 Summer 2009 Sons of Union GRAND ARMY OF THE REPUBLIC IN MESA CO Veterans of the Civil Article by Gary E. Parrott, PDC De- War partment of CO/WY Department of CO/WY 2960 great Plains Drive Grand Junction, CO 81503 MMMesa County just completed (970) 243-0476 th celebrating its 125 Anniver- NEW OFFICERS Commander sary. Many of the service and Garry W. Brewer, PCC fraternal organizations active 2722 Rincon Drive Grand Junction, Colorado 81503 today in the Grand Valley can 970-241-5842 trace their roots back to the first [email protected] Senior Vice Commander days of Mesa County. One of Rhy Paris, PCC the first such orders was the 494 Bing Street Grand Junction, CO 81504-6113 Grand Army of the Republic 970-434-0410 [email protected] (GAR), the largest and most in- Junior Vice Commander fluential veteran service organi- Eric D. Richhart, PCC zation of its era. 3844 S. Danbury Circle Magna, UT 84044-2223 801-250-7733 The GAR was a national or- [email protected] ganization established on April Secretary / Treasurer 6, 1866 (just after the official Gary E. Parrott, PDC 2960 Great Plains Drive end of the Civil War) in Deca- Grand Junction, CO 81503 970-243-0476 tur, Illinois. Its members were [email protected] former soldiers, sailors and ma- Counselor William Ray Ward, PDC rines who had honorably served P.O. Box 11592 this country during the Civil War. Salt Lake City, UT 84147-0592 801-359-6833 The GAR was intended to be a fraternal and benevolence society.