The Miami Circle and Archaeological Preservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

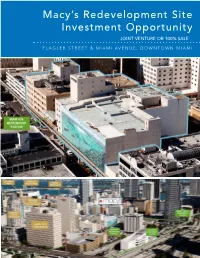

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Historic and Environmental Preservation Board Staff Report

ITEM 7 HISTORIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL PRESERVATION BOARD STAFF REPORT NAME 8DA11 / Dupont Archaeological Conservation Area ADDRESS 300 SE 3 Street PROJECT DESCRIPTION Preliminary evaluation of data to determine conformance with City of Miami Preservation Ordinance requirements for local designation of 300 SE 3 Street as an historic and archaeological site; if appropriate, directing the Planning Department to prepare a designation report PREFACE It is essential to note that until archaeological excavations are concluded and artifact analysis and technical report production is completed by the project archaeologist, the significance of the parcel at 300 SE 3 Street (hereinafter referred to as “the Site”) can only be understood as it relates to the historical record, to previous technical archaeological reports produced for adjacent properties, and the preliminary findings on the Site itself. Due to the in-progress nature of archaeological study at the Site, official interpretation of the exact archaeological significance of the Site may evolve. ANALYSIS The parcel at 300 SE 3 Street (hereinafter referred to as “the Site”) is located on Miami’s prehistoric shoreline, where the Miami River once met Biscayne Bay. The Site has always been prime real estate in Miami. Archaeological data obtained from adjacent sites indicate that Native American settlement at the site dates back approximately 2,000 years. The first written accounts of Spanish explorers in South Florida from the early 1500s note that a Tequesta village was located at the mouth of the Miami River, and that it was one of the largest Native American settlements in South Florida. In the historic record, accounts have been made that the Site or the immediately adjacent areas hosted 16th and 17th century Spanish missions and an 18th-century plantation. -

Free Expression and Intellectual Diversity How Florida Universities Currently Measure Up

POLICY BRIEF Free Expression and Intellectual Diversity How Florida Universities Currently Measure Up William Mattox Director of the J. Stanley Marshall Center for Educational Options iddlebury College. University of California, Berkeley. Evergreen State. MClaremont McKenna. Yale. The list of academic institutions rocked in recent months by (sometimes violent) speech-squelching protests is not pretty. And combined with growing concerns about high student debt and sagging job prospects for many new graduates, these efforts to thwart campus discourse are causing many people – for the first time ever – to question whether higher education is truly worth the investment it requires. www.jamesmadison.org | 1 For example, a 2017 survey by the Pew Research Center found campus craziness presents an opportunity for our state. For if the that 58 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning indepen- Florida higher education system were to become a haven for free dents now believe colleges and universities are having a negative expression and viewpoint diversity – and to become known as effect on the direction of our country. This represents a whop- such – our universities would be very well positioned to meet the ping 21 percent shift since 2015 (when 37 percent of center-right growing demand for intellectually-serious academic study at an Americans viewed the performance of higher education institu- affordable cost. tions negatively).1 In fact, a major 2013 report said as much. Growing skepticism about the current direction of American In 2013, the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA) higher education isn’t just found among those on the center-right. produced a comprehensive report on the state of higher education For example, a center-left New York University professor named in Florida (with assistance from The James Madison Institute). -

Devoe L. Moore Center Symposium on Filmmaking, Education, and Public Policy Information Brief for Potential Partners & Affiliates

DeVoe L. Moore Center Symposium on Filmmaking, Education, and Public Policy Information Brief for Potential Partners & Affiliates About the Symposium: On FEBRUARY 9TH, 2021, The DeVoe L. Moore Center at Florida State University is hosting our annual symposium on Filmmaking and Public Policy in February with a focus on education reform. We will be screening and analyzing the 2019 film Miss Virginia, directed by R.J. Daniel Hanna and executive produced by Nick Reid. Our symposium will include the following sections and each panel will be followed by a Q&A: ◘ Filmmaking and Storytelling Panel | 2:30 — 3:30PM | Click Here to Register A discussion with Executive Producer Nick Reid and film Director Daniel Hanna about the creative process and how public policy influences filmmaking from a creative perspective. They will discuss how film and other creative projects are important vehicles for policy reform and nonpartisan discussions. ◘ Screening of Miss Virginia | 4:00 — 6:00PM | Click Here to Register A live screening of Miss Virginia, offered in-person at the FSU student theater (ASLC) and online via Zoom for virtual participants. ◘ Public Policy Panel on School Choice | 6:30 — 8:00PM | Click Here to Register A collaborative conversation about education policy in Florida and the nation including leading policy experts. Engaging Our Audience: The symposium is founded on Florida State University’s core values of Inspired Excellence and Dynamic Inclusiveness. Achieving these goals requires the passionate participation of our audience at FSU and beyond. To foster a mutually beneficial relationship, we hope our affiliate organizations and individuals will consider avenues such as professional education credits or extra credit for academic coursework. -

The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19Th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2017 The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia Julianna Geralynn Jackson College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Julianna Geralynn, "The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia" (2017). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1516639577. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/S2V95T This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia Julianna Geralynn Jackson Baldwin, Maryland Bachelor of Arts, St. Mary’s College of Maryland, 2012 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of The College of William & Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of William & Mary August, 2017 © Copyright by Julianna Geralynn Jackson 2017 ABSTRACT This project uses archaeology, architecture, and the documentary record to explore the ways in which one family, the Tayloes, used Georgian design principals as a way of exerting control over the 19th-century landscape. -

Miami Office Space Can Be Found by Those Who Search February 7, 2017 By: Carla Vianna

Miami Office Space Can Be Found by Those Who Search February 7, 2017 By: Carla Vianna Businesses searching for space in Miami's urban core have more options than they might think. While vacancy rates are down across the board, significant chunks of space are available in several Class A buildings in downtown and the Brickell Avenue financial district. "There are more alternatives available for those companies that take the time to appropriately investigate the market," said Chris Lovell, a senior managing director with Savills Studley in Miami. Leasing space on an upper floor with a view may be difficult since only six buildings on Brickell have a full floor above the 20th story available for lease. For tenants that can live without the view, there is plenty of open space to choose from. Four downtown Class A buildings have at least 75,000 square feet of contiguous space available, one Class A building on Brickell has a 65,000- square-foot block — "and we don't have tenants of that size standing in line to the claim the space," Lovell said. Savills Studley has found many of the large available blocks are in older downtown buildings. "You're always going to have buildings that are going to have certain pockets available," said Tere Blanca, founder of Miami-based Blanca Commercial Real Estate Inc. She said the market is responding well to the new Miami Central project, which is under construction with 60 percent of its office component pre- leased. The mixed-use development will serve as Brightline's downtown train station and will add 286,000 square feet of office space in two buildings. -

Supporting Plaintiffs-Appellants ______

Case: 09-5342 Document: 1215951 Filed: 11/16/2009 Page: 1 ORAL ARGUMENT SCHEDULED FOR JANUARY 27, 2010 No. 09-5342 (consolidated with No. 08-5223) __________________ UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT DAVID KEATING, EDWARD H. CRANE, III, FRED M. YOUNG, JR., BRAD RUSSO, AND SCOTT BURKHARDT, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION, Defendant-Appellee. __________________ On Certified Questions from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, Case No. 08-cv-00248 (JR) __________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE Alliance for Justice, Concerned Women for America Legislative Action Committee, FRC Action, The Commonwealth Foundation for Public Policy Alternatives, Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Caesar Rodney Institute, Kansas Policy Institute, FreedomWorks Foundation, The James Madison Institute, Public Interest Institute Supporting Plaintiffs-Appellants __________________ Heidi K. Abegg (DC Bar No. 463935) Alan P. Dye (DC Bar No. 215319) WEBSTER, CHAMBERLAIN & BEAN 1747 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Suite 1000 Washington, DC 20006 Tel: (202) 785-9500 Counsel for Amici Curiae Dated: November 16, 2009 Case: 09-5342 Document: 1215951 Filed: 11/16/2009 Page: 2 CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS, AND RELATED CASES All parties appearing in this Court are listed in the Brief for Appellants David Keating, Fred M. Young, Jr., Edward H. Crane, III, Brad Russo, and Scott Burkhardt, as are references to the rulings and related cases. CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure and D.C. Circuit Rule 26.1, amicus curiae Alliance for Justice states that it is a non-profit corporation, exempt from taxation under § 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, it has no parent corporation, and is not a publicly held corporation that issues stock. -

Welcome to Kaplan Medical

Welcome to Kaplan Medical 4425 Ponce De Leon, #1612 Coral Gables, FL 33146 Miami Kaplan Center 4425 Ponce De Leon Boulevard Suite 1612 Coral Gables, FL 33146 Hours of Operation Monday-Thursday 9am - 9pm Friday-Sunday 10am - 5pm (305) 441-5323, Ext. 5000 or 5002 2 Our Neighborhood Coral Gables: Coral Gables’ founders imagined both a “City Beautiful” and a “Garden City,” with lush green avenues winding through a residential city, punctuated by civic landmarks and embellished with detailed and playful architectural features. Known as The City Beautiful, Coral Gables stands out as a planned community that blends color, details, and the Mediterranean Revival architectural style. International: From its inception, Coral Gables was designed to be an international City, and is now home to more than 20 consulates and foreign government offices and more than 140 multinational corporations. As early as 1925, City Founder George Merrick predicted Coral Gables would serve as "a gateway to Latin America." To further establish international ties, the City has forged relationships with six Sister Cities: Aix-en Provence, France; Cartagena, Colombia; Granada, Spain; La Antigua, Guatemala; Province of Pisa, Italy; and Quito, Ecuador (emeritus). 3 Our Neighborhood University of Miami: The University of Miami is located in Coral Gables Shopping: Coral Gables attracts national and regional retailers along with an abundance of boutiques and retail shops. Miracle Mile is the center of a true downtown district. Located across the street from the Kaplan Medical Center in Coral Gables is “The Village of Merrick Park”, a 780,000 square foot retail, residential and office project anchored by Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom, and has more than 100 other select retailers including Tiffany & Co., Burberry, Coach and Gucci. -

Met 1 Miami Brochure

m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a nm e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a n m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a nm e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a n m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a nm e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a n heads up, downtown! the renaissance of miami’s oldest neighborhood is on the move. -

Education Performance in Florida: a Need for Change. Policy Report

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 461 935 EA 031 530 AUTHOR Moore, Edwin H. TITLE Education Performance in Florida: A Need for Change. Policy Report. Backgrounder. INSTITUTION James Madison Inst., Tallahassee, FL. REPORT NO JMI-R-30 PUB DATE 2001-03-00 NOTE 23p.; The "Backgrounder" is published six times a year to encourage public debate on public issues in Florida. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.jamesmadison.org. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Blue Ribbon Commissions; *Change Strategies; *Educational Change; *Educational Improvement; *Educational Quality; Elementary Secondary Education; Higher Education; State Boards of Education; State Legislation; *State Regulation; Statewide Planning IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT In 1998, the citizens of Florida approved passage of Amendment VIII to the Florida Constitution, whereby the voters voluntarily gave up their right to elect a commissioner of education and a state board of education. In 1999, the standing commissioner of education appointed a blue-ribbon committee to review and recommend changes to the Florida system. In 2000, a state task force was appointed to lay the groundwork for system transition by 2003, work that is now completed. This report evaluates the current state of affairs in the Florida educational system. Questions addressed include:(1) Why change the organizational structures? (2) How successful has Florida been in delivering education services? and (3) Does the current system have a coordinated statewide system? Florida ranked 46th nationally in a study of performance of high school graduation rates for the 1999-2000 school year; opposition still exists within some institutions of higher education to creating a unified K-20 educational system; and there is still lack of coordination between different levels of education. -

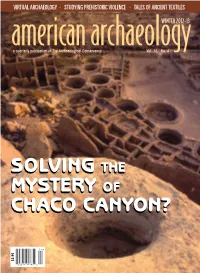

Solving the Mystery of Chaco Canyon?

VIRTUALBANNER ARCHAEOLOGY BANNER • BANNER STUDYING • BANNER PREHISTORIC BANNER VIOLENCE BANNER • T •ALE BANNERS OF A NCIENT BANNER TEXTILE S american archaeologyWINTER 2012-13 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 SOLVINGSOLVING THETHE MYMYSSTERYTERY OFOF CHACHACCOO CANYONCANYON?? $3.95 $3.95 WINTER 2012-13 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 26 CHACO, THROUGH A DIFFERENT LENS BY MIKE TONER Southwest scholar Steve Lekson has taken an unconventional approach to solving the mystery of Chaco Canyon. 12 VIRTUALLY RECREATING THE PAST BY JULIAN SMITH Virtual archaeology has remarkable potential, but it also has some issues to resolve. 19 A ROAD TO THE PAST BY ALISON MCCOOK A dig resulting from a highway project is yielding insights into Delaware’s colonial history. 33 THE TALES OF ANCIENT TEXTILES BY PAULA NEELY Fabric artifacts are providing a relatively new line of evidence for archaeologists. 39 UNDERSTANDING PREHISTORIC VIOLENCE BY DAN FERBER Bioarchaeologists have gone beyond studying the manifestations of ancient violence to examining CHAZ EVANS the conditions that caused it. 26 45 new acquisition A TRAIL TO PREHISTORY The Conservancy saves a trailhead leading to an important Sinagua settlement. 46 new acquisition NORTHERNMOST CHACO CANYON OUTLIER TO BE PRESERVED Carhart Pueblo holds clues to the broader Chaco regional system. 48 point acquisition A GLIMPSE OF A MAJOR TRANSITION D LEVY R Herd Village could reveal information about the change from the Basketmaker III to the Pueblo I phase. RICHA 12 2 Lay of the Land 50 Field Notes 52 RevieWS 54 Expeditions 3 Letters 5 Events COVER: Pueblo Bonito is one of the great houses at Chaco Canyon. -

Community Relations Plan

Miami International Airport Community Relations Plan Preface .............................................................................................................. 1 Overview of the CRP ......................................................................................... 2 NCP Background ............................................................................................... 3 National Contingency Plan .............................................................................................................. 3 Government Oversight.................................................................................................................... 4 Site Description and History ............................................................................. 5 Site Description .............................................................................................................................. 5 Site History .................................................................................................................................... 5 Goals of the CRP ............................................................................................... 8 Community Relations Activities........................................................................ 9 Appendix A – Site Map .................................................................................... 10 Appendix B – Contact List............................................................................... 11 Federal Officials ..........................................................................................................................