Myanmar/Burma - Muslims and Rohingya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title <Article>Phonology of Burmese Loanwords in Jinghpaw Author(S)

Title <Article>Phonology of Burmese loanwords in Jinghpaw Author(s) KURABE, Keita Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2016), 35: 91-128 Issue Date 2016-12-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/219015 Right © 京都大学言語学研究室 2016 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 35 (2016), 91 –128 Phonology of Burmese loanwords in Jinghpaw Keita KURABE Abstract: The aim of this paper is to provide a preliminary descriptive account of the phonological properties of Burmese loans in Jinghpaw especially focusing on their segmental phonology. Burmese loan phonology in Jinghpaw is significant in two respects. First, a large portion of Burmese loans, despite the fact that the contact relationship between Burmese and Jinghpaw appears to be of relatively recent ori- gin, retains several phonological properties of Written Burmese that have been lost in the modern language. This fact can be explained in terms of borrowing chains, i.e. Burmese Shan Jinghpaw, where Shan, which has had intensive contact → → with both Burmese and Jinghpaw from the early stages, transferred lexical items of Burmese origin into Jinghpaw. Second, the Jinghpaw lexicon also contains some Burmese loans reflecting the phonology of Modern Burmese. These facts highlight the multistratal nature of Burmese loans in Jinghpaw. A large portion of this paper is devoted to building a lexicon of Burmese loans in Jinghpaw together with loans from other relevant languages whose lexical items entered Jinghpaw through the medium of Burmese.∗ Key words: Burmese, Jinghpaw, Shan, loanwords, contact linguistics 1 Introduction Jinghpaw is a Tibeto-Burman (TB) language spoken primarily in northern Burma (Myan- mar) where, as with other regions of Southeast Asia, intensive contact among speakers ∗ I would like to thank Professor Hideo Sawada and Professor Keisuke Huziwara for their careful reading and helpful suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper. -

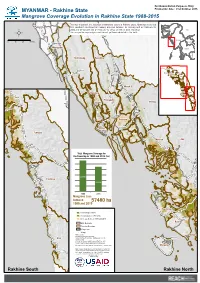

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

139416 Rakhine State

Rakhine State (Myanmar) as of 22 May 2013 Total Estimated IDP Population 139,416 Total Number of Households 22,773 Rakhine Situation Overview Inter-community conflict in Rakhine State, which erupted in early June 2012 and resurfaced in October 2012, has resulted in displacement and loss of lives and livelihoods. As of beginning of April 2013, the number of people displaced in Rakhine State has surpassed 139,000, of whom about 75,000 displaced since June 2012 and the remaining following Kyauktaw October. Many others continue living in tents close to their places of origin while their houses are being rebuilt, or with Maungdaw 6418 host families. The IDP population is currently hosted in 76 camps and camp-like settings. The Shelter/NFI/CCCM Cluster 3569 was activated in December 2012 in Yangon. Only more recently (middle March 2013) did the CCCM Cluster become Mrauk-U operational in Rakhine State. Therefore the sectoral response is still at a very early stage at field level. Rathedaung 4135 4008 Minbya Number of IDP sites by township IDP population by township 5152 as of 22 May 2013 as of 22 May 2013 Sittwe Pauktaw Minbya 8 Minbya 5,152 19976 Meybon Mrauk-U 4 Mrauk-U 4,135 89880 4169 Meybon 2 Meybon 4,169 Pauktaw 6 Pauktaw 19,976 Kyauktaw 11 Kyauktaw 6,418 Rathedaung 4 Rathedaung 4,008 Kyauk Phyu 2 Kyauk Phyu 1,849 Kyauk Phyu Ramree 2 Rakhine Ramree 260 1849 Sittwe 23 Sittwe 89,880 Maungdaw 14 Maungdaw 3,569 Type of accomodation at IDP sites Ramree Number of IDP sites IDP population by type of 260 'Planned / Managed Camp' purpose-built sites by type of accommodation accommodation where services and infrastructure is provided 139,416IDPs including water supply, food distribution, non- food item, education, and health care, usually targeted by humanitarian partners exclusively for the population of the site. -

Development of Local Theology of the Chin (Zomi) of the Assemblies of God (Ag) in Myanmar: a Case Study in Contextualization

DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL THEOLOGY OF THE CHIN (ZOMI) OF THE ASSEMBLIES OF GOD (AG) IN MYANMAR: A CASE STUDY IN CONTEXTUALIZATION BY DENISE ROSS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion THE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM January 2019 This thesis is dedicated firstly to my loving parents Albert and Hilda Ross from whom I got the work ethic required to complete this research. Secondly, I dedicate it to the Chin people who were generous in telling me their stories, so I offer this completed research as a reflection for even greater understanding and growth. Acknowledgements This thesis took many years to produce, and I would like to acknowledge and thank everyone who encouraged and supported me throughout the often painful process. I would like to thank Edmond Tang for his tremendous supervision for several years. He challenged me, above all else, to think. I can never acknowledge or thank him sufficiently for the time and sacrifice he has invested. I would like to thank my supervisor Allan Anderson, who has been so patient and supportive throughout the whole process. I would like to acknowledge him as a pillar of Pentecostal research within the University of Birmingham, UK which has made it an international centre of excellence. It was his own research on contextual theology, especially in mission contexts, which inspired this research. I acknowledge the Chin interviewees and former classmates who willingly shared their time and expertise and their spiritual lives with me. They were so grateful that I chose their people group, so I offer this research back to them, in gratitude. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.ukbrought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright 1 A STUDY OF THE APADĀNA, INCLUDING AN EDITION AND ANNOTATED TRANSLATION OF THE SECOND, THIRD AND FOURTH CHAPTERS CHRIS CLARK A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney May 2015 ii CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................. -

Buddhism and Written Law: Dhammasattha Manuscripts and Texts in Premodern Burma

BUDDHISM AND WRITTEN LAW: DHAMMASATTHA MANUSCRIPTS AND TEXTS IN PREMODERN BURMA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Dietrich Christian Lammerts May 2010 2010 Dietrich Christian Lammerts BUDDHISM AND WRITTEN LAW: DHAMMASATTHA MANUSCRIPTS AND TEXTS IN PREMODERN BURMA Dietrich Christian Lammerts, Ph.D. Cornell University 2010 This dissertation examines the regional and local histories of dhammasattha, the preeminent Pali, bilingual, and vernacular genre of Buddhist legal literature transmitted in premodern Burma and Southeast Asia. It provides the first critical analysis of the dating, content, form, and function of surviving dhammasattha texts based on a careful study of hitherto unexamined Burmese and Pali manuscripts. It underscores the importance for Buddhist and Southeast Asian Studies of paying careful attention to complex manuscript traditions, multilingual post- and para- canonical literatures, commentarial strategies, and the regional South-Southeast Asian literary, historical, and religious context of the development of local legal and textual practices. Part One traces the genesis of dhammasattha during the first and early second millennia C.E. through inscriptions and literary texts from India, Cambodia, Campå, Java, Lakå, and Burma and investigates its historical and legal-theoretical relationships with the Sanskrit Bråhmaˆical dharmaßåstra tradition and Pali Buddhist literature. It argues that during this period aspects of this genre of written law, akin to other disciplines such as alchemy or medicine, functioned in both Buddhist and Bråhmaˆical contexts, and that this ecumenical legal culture persisted in certain areas such as Burma and Java well into the early modern period. -

Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State

ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 1/2 RH PT Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State (Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit) http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/State_Map_D istrict_Rakhine_MIMU764v04_23Oct2017_A4.pdf ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 2/2 RH PT Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Rakhine State 92° EBANGLADESH 93° E 94° E 95° E Pauk !( Kyaukhtu INDIA Mindat Pakokku Paletwa CHINA Maungdaw !( Samee Ü Taungpyoletwea Nyaung-U !( Kanpetlet Ngathayouk CHIN STATE Saw Bagan !( Buthidaung !( Maungdaw District 21° N THAILAND 21° N SeikphyuChauk Buthidaung Kyauktaw Kyauktaw Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Mrauk-U Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Mrauk-U District Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Sittwe DistrictPonnagyun Pauktaw Sittwe Saku !( Minbu Pauktaw .! Ngape .! Sittwe Myebon Ann Magway Myebon 20° N RAKHINE STATE Minhla 20° N Ann MAGWAY REGION Sinbaungwe Kyaukpyu District Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu !( Mindon Ramree Toungup Ramree Kamma 19° N 19° N Bay of Bengal Munaung Toungup Munaung Padaung Thandwe District BAGO REGION Thandwe Thandwe Kyangin Legend .! State/Region Capital Main Town !( Other Town Kyeintali !( 18° N Coast Line 18° N Map ID: MIMU764v04 Township Boundary Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 State/Region Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 International Boundary Data Sources: MIMU Gwa Base Map: MIMU Road Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Kyaukpyu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Gwa translated by MIMU Maungdaw Mrauk-U Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Sittwe Ngathaingchaung Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers !( Thandwe 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 15 30 60 Yegyi 92° E 93° E 94° E 95° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Proto Northern Burmic Is Reconstructed on the Basis of Data from Achang, Bela, Lashi

1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.0 Introduction The basic purpose of this thesis is to provide a reconstruction of Proto Northern Burmic and to describe the phonological relationships between the Northern Burmic languages. This work is relevant as a thorough analysis of this language family has not yet been conducted. This analysis relies primarily on data from six Northern Burmic languages, with the additional resource of Written Burmese. In chapter 1, the background information on the languages under study and the basic approach of the thesis are described, chapter 2 gives a description of the lang-uages. The reconstruction is provided in chapter 3. A description of Proto Northern Burmic and a discussion of the phonological relationships between the Northern Burmic languages is given in chapter 4. Reconstructed vocabulary is entailed in chapter 5. This chapter provides background information for this thesis such as a description of the Northern Burmic peoples, linguistic classification, literature review, historical reconstruction methodology, a brief statement of purpose, as well as sources for the linguistic data. 1.1 Northern Burmic Historical, Cultural and Geographic Background The term Northern Burmic (Shafer 1966) is used in this thesis to refer to the grouping of Achang, Bela, Lashi, Maru, Phon, and Zaiwa. The primary data for this thesis is from speakers in the Kachin State in NE Myanmar (Burma) near the border of Yunnan, China (see section 1.7 for discussion of data). It must be stressed that this is by no means the only area in which these 2 languages are spoken as these language groups straddle the rugged mountain peaks between China and Myanmar. -

DRC Myanmar Poverty and Hunger Alleviation Through

DRC Myanmar│ Poverty and Hunger Alleviation through Support, Empowerment, and Increased Networking (PHASE IN II) via the European Union PROJECT SNAPSHOT │ Community-driven Development in Sittwe Township of Rakhine State Bringing communities out of isolation and closer to each other and to markets is one of the keys to development in Myanmar’s Rakhine state to create access, break the poverty cycle and strengthen resilience. DRC’s Community-driven Development project in Rakhine is one such approach that aims to empower individuals and entire communities. Infrastructure is the overall theme for these types of projects that are designed and implemented by DRC with communities in rural areas. The community decides In close collaboration with key stakeholders, committed citizens and community representatives, DRC introduces participatory processes to develop ideas and plans for local infrastructure projects. These can be linked to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), Disaster Risk Reduction (DDR), food security or community cohesion. The needs are identified and prioritised collectively through the establishment of Village Development Committees to ensure local ownership and social cohesion. The committees are composed to reflect age, gender and diversity in each community, to ensure that men and women, of different ages, across the community are heard and involved. Roads Since 2018, DRC has worked with five villages in Aung Daing, in Sittwe Township of Rakhine State. A rapid needs assessment made it clear that new roads were their key priority as the villages all suffer from isolation due to roads that are old or damaged by seasonal floods. Road construction was eventually were carried out in three Rohingya villages using macadam engineering, and concrete road construction in two other Rakhine villages. -

Internal Displacement in Rakhine State (1 May 2014)

Myanmar: Internal Displacement in Rakhine State (1 May 2014) ! IDP Camp Tilin !( Administrative Towns P State Capital !( !( Township Centre BANGLADESH Roads IDP per Township CHIN !( 255 - 10,000 !( Saw 10,001 - 20,000 !( 20,001 - 92,692 !( Ocean & Seas ! International Boundary State Boundary Buthidaung ! Maungdaw !( !! !!( Township Boundary !!!(!! Kyauktaw !! ! CHINA !! !!! Mrauk-U BHUTAN !( ! ! !! INDIA CHINA KA CHIN Rathedaung !H !( ! Sidoktaya !! BANGLADESH ! ! ! !!! !!( RAKHINE Ponnagyun CHIN !( !H ! Minbya BANGLADESH MAN DA LAY SA GAING !H !H ! Pauktaw SHA N (S OU TH) !Sittwe !H ! !( LAOS !!! RAK HINE MAGWAY !!!!! ! !H !H !!!! NAY PYI TAW !!P !\ !HKAYAH !! ! ! Myebon !!( Bay ! LAOS BA GO E AS T of !H Bay KAY IN AY E YA RWA DY YA NGON !H Bengal of !H !H !HMON Bengal THAILAND Gulf of Martaban !( TAN INTH ARY I !H Thin Pone Tan ! Gulf of Thailand Andaman Sea Ohn Taw Chay !!!( ! Say Tha Mar Gyi Kyaukpyu No. Reported ! Township camps IDPs Kyaukpyu 2 1,782 Ohn Taw Gyi (North) Kyauktaw 11 6,795 Maw Ti Ngar ! Thet Kae Pyin Maungdaw 9 1,911 Khaung Doke Khar! (IDPs in host family) Ohn Taw Gyi (South) !! Myebon 2 3,234 Baw Du Pha (IDP in host families) !! ! ! ! Minbya 7 5,306 Baw Du Pha 2 Mrauk_U 4 4,072 Baw Du Pha 1 Thet Kae Pyin !( Ramree!! Pauktaw 5 1 7,258 Dar Pai (IDP in host families) Dar Pai! Ramree 2 2 55 ! Rathedaung 5 4,089 Thae Chaung Sittwe 21 9 2,692 Set Yone Su 3 Sat Roe Kya ! 1 Total 68 137,394 !Sat Roe Kya Thae Chaung (IDP in host families) 2 ! !( Map Doc Name: ! MMR_0131_Rakhine_IDPs_A3_Portrait_140501 Set Yone Su Map reference Number: MMR_0131 Munaung Creation Date: 11 June 2014 Projection/Datum: D_WGS_1984 SittweP Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:1,022,944 Basare ! 0 10 20 Kilometers 0 10 20 Miles Map data source(s): Admin data: GAD processed by MIMU Source of data: OCHA, Camp Coordinatioin and Camp Mamangement (CCCM) Cluster. -

Language Choice in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities

Language Choice in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities Summary of a Workshop Discussion Organised by the British Academy in Partnership with the École française d’Extrême-Orient 14 February 2015 Yangon, Myanmar Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 English in Myanmar: a Brief Overview 5 English in Burmese Universities 6 The Experiences of Other Countries 7 Malaysia 7 Thailand 8 Other Countries in Asia and Beyond 8 Observations and Issues for Further Consideration 11 About the British Academy 13 About the École française d’Extrême-Orient 13 2 Language Choice in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities Executive Summary Is English the best medium of instruction for higher education in Myanmar, and, if so, does the solution to current problems in local universities lie in introducing more intensive English-language teaching at the primary and secondary levels? The British Academy and the École française d’Extrême-Orient brought together a group of distinguished experts from Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Australia and the UK, to consider these questions and promote the sharing of lessons among countries in the Southeast Asia region and beyond. This report summarises the outcomes of the discussion and puts forward a number of key messages, with a view to informing the ongoing Myanmar Comprehensive Education Sector Review process: • The best language policy choice for universities in Myanmar may not be either English or Burmese, but some combination of the two. • Language support in Burmese or in English should be extended to students who do not have sufficient language skills to cope adequately with the learning process. • Professional development training for lecturers aimed at improving teaching techniques is needed, including strategies for Burmese and English. -

Old Burmese Ry- – a Remark on Proto-Lolo-Burmese Resonant Initials1

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS Vol. 10.2 (2017): i-x ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52407 University of Hawaiʼi Press eVols OLD BURMESE RY- – A REMARK ON PROTO-LOLO-BURMESE RESONANT INITIALS1 Yoshio Nishi (Translated via Nathan W. Hill) Kobe City University of Foreign Studies (emeritus) Abstract Philological evidence and comparative phonology confirm the existence of an initial ry- in Old Burmese and Proto-Lolo-Burmese, evidence that is over looked in much scholarship (e.g. Matisoff 1979, 1991, etc.). Keywords: Old Burmese, Prolo-Lolo-Burmese, liquid initials, reconstruction ISO 639-3 codes: obr, mya, ahk, atb, hni, lis, lhu, ywq We may cite the following four words that are spelled with ry- in Old Burmese (OB) and have cognates in other Lolo-Burmese (LB) languages.i A. 1. ryā ‘hundred’: WrB rá, 2. ryā ‘(dry-crop) field’: WrB rá (now spelled yá)ii 3. ryak ‘day’: WrB rakiii 4. ryap ‘to stand’: WrB rapiv Furthermore, in OB (or Pre-OB), there is a word that one may presume to begin with initial /*hry-/: B. 1. *hryat ‘eight’: WrB hracv Other examples of OB forms with an initial spelling ry- are found among loanwords or words with unclear origin: C. Loanwords e.g., 1. (Ɂa-cī) Ɂa-ryaŋ ‘arrangement’: WrB (Ɂa-cí) Ɂa-ráŋvi 2. charyā ‘abbot, teacher’: WrB charávii 3. taryā ‘1aw’: WrB taráviii 4. (Ɂari)mitt(i/a)ryā ‘Maitreya’: WrB (Ɂari)metteyyaix 5. san-ryan ‘a kind of sedan-chair’: WrB san-lyâŋ/ san-hlâŋ /sam-lyâŋ/ sam-hlyâŋx 1 At the retirement of Professor Yoshio Nishi, most of his research on Burmese was anthologized in Four Papers on Burmese (Tokyo, 1999), but two of his early papers, written in Japanese, were excluded.