The Stories of Serenade: Nonprofit History and George Balanchine's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerie Roche ARAD Director Momix and the Omaha Ballet

Celebrating 50 years of Dance The lights go down.The orchestra begins to play. Dancers appear and there’s magic on the stage. The Omaha Academy of Ballet, a dream by its founders for a school and a civic ballet company for Omaha, was realized by the gift of two remarkable people: Valerie Roche ARAD director of the school and the late Lee Lubbers S.J., of Creighton University. Lubbers served as Board President and production manager, while Roche choreographed, rehearsed and directed the students during their performances. The dream to have a ballet company for the city of Omaha had begun. Lubbers also hired Roche later that year to teach dance at the university. This decision helped establish the creation of a Fine and Performing Arts Department at Creighton. The Academy has thrived for 50 years, thanks to hundreds of volunteers, donors, instructors, parents and above all the students. Over the decades, the Academy has trained many dancers who have gone on to become members of professional dance companies such as: the American Ballet Theatre, Los Angeles Ballet, Houston Ballet, National Ballet, Dance Theatre of Harlem, San Francisco Ballet, Minnesota Dance Theatre, Denver Ballet, Momix and the Omaha Ballet. Our dancers have also reached beyond the United States to join: The Royal Winnipeg in Canada and the Frankfurt Ballet in Germany. OMAHA WORLD HERALD WORLD OMAHA 01 studying the work of August Birth of a Dream. Bournonville. At Creighton she adopted the syllabi of the Imperial Society for Teachers The Omaha Regional Ballet In 1971 with a grant and until her retirement in 2002. -

Press Release

Press Release Contact: Whitney Museum of American Art Whitney Museum of American Art 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street Stephen Soba, Kira Garcia New York, NY 10021 (212) 570-3633 www.whitney.org/press www.whitney.org/press March 2007 Tel. (212) 570-3633 Fax (212) 570-4169 [email protected] WHITNEY MUSEUM TO PRESENT A TRIBUTE TO LINCOLN KIRSTEIN BEGINNING APRIL 25, 2007 Pavel Tchelitchew, Portrait of Lincoln Kirstein, 1937 Courtesy of The School of American Ballet, Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson The Whitney Museum of American Art is observing the 100th anniversary of Lincoln Kirstein’s birth with an exhibition focusing on a diverse trio of artists from Kirstein’s circle: Walker Evans, Elie Nadelman, and Pavel Tchelitchew. Lincoln Kirstein: An Anniversary Celebration, conceived by guest curator Jerry L. Thompson, working with Elisabeth Sussman and Carter Foster, opens in the Museum’s 5th-floor Ames Gallery on April 25, 2007. Selections from Kirstein’s writings form the basis of the labels and wall texts. Lincoln Kirstein (1906-96), a noted writer, scholar, collector, impresario, champion of artists, and a hugely influential force in American culture, engaged with many notable artistic and literary figures, and helped shape the way the arts developed in America from the late 1920s onward. His involvement with choreographer George Balanchine, with whom he founded the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet, is perhaps his best known accomplishment. This exhibition focuses on the photographer Walker Evans, the sculptor Elie Nadelman, and the painter Pavel Tchelitchew, each of whom was important to Kirstein. -

Singapore Dance Theatre Launches 25 Season with Coppélia

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | JANEK SCHERGEN FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT Melissa Tan Publicity and Advertising Executive [email protected] Joseph See Acting Marketing Manager [email protected] Office: (65) 6338 0611 Fax: (65) 6338 9748 www.singaporedancetheatre.com Singapore Dance Theatre Launches 25th Season with Coppélia 14 - 17 March 2013 at the Esplanade Theatre As Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT) celebrates its 25th Silver Anniversary, the Company is proud to open its 2013 season with one of the most well-loved comedy ballets, Coppélia – The Girl with Enamel Eyes. From 14 – 17 March at the Esplanade Theatre, SDT will mesmerise audiences with this charming and sentimental tale of adventure, mistaken identity and a beautiful life-sized doll. A new staging by Artistic Director Janek Schergen, featuring original choreography by Arthur Saint-Leon, Coppélia is set to a ballet libretto by Charles Nuittier, with music by Léo Delibes. Based on a story by E.T.A. Hoffman, this three-act ballet tells the light-hearted story of the mysterious Dr Coppélius who owns a beautiful life-sized puppet, Coppélia. A village youth named Franz, betrothed to the beautiful Swanilda becomes infatuated with Coppélia, not knowing that she just a doll. The magic and fun begins when Coppélia springs to life! Coppélia is one of the most performed and favourite full-length classical ballets from SDT’s repertoire. This colourful ballet was first performed by SDT in 1995 with staging by Colin Peasley of The Australian Ballet. Following this, the production was revived again in 1997, 2001 and 2007. This year, Artistic Director Janek Schergen will be bringing this ballet back to life with a new staging. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Hans Ulrich Obrist a Brief History of Curating

Hans Ulrich Obrist A Brief History of Curating JRP | RINGIER & LES PRESSES DU REEL 2 To the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Pontus Hultén, Jean Leering, Franz Meyer, and Harald Szeemann 3 Christophe Cherix When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked the former director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Anne d’Harnoncourt, what advice she would give to a young curator entering the world of today’s more popular but less experimental museums, in her response she recalled with admiration Gilbert & George’s famous ode to art: “I think my advice would probably not change very much; it is to look and look and look, and then to look again, because nothing replaces looking … I am not being in Duchamp’s words ‘only retinal,’ I don’t mean that. I mean to be with art—I always thought that was a wonderful phrase of Gilbert & George’s, ‘to be with art is all we ask.’” How can one be fully with art? In other words, can art be experienced directly in a society that has produced so much discourse and built so many structures to guide the spectator? Gilbert & George’s answer is to consider art as a deity: “Oh Art where did you come from, who mothered such a strange being. For what kind of people are you: are you for the feeble-of-mind, are you for the poor-at-heart, art for those with no soul. Are you a branch of nature’s fantastic network or are you an invention of some ambitious man? Do you come from a long line of arts? For every artist is born in the usual way and we have never seen a young artist. -

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

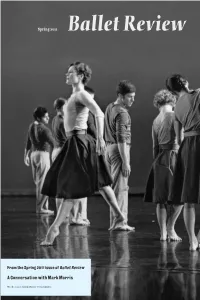

A Conversation with Mark Morris

Spring2011 Ballet Review From the Spring 2011 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Mark Morris On the cover: Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. 4 Paris – Peter Sparling 6 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 8 Stupgart – Gary Smith 10 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 13 Paris – Peter Sparling 15 Sarasota, FL – Joseph Houseal 17 Paris – Peter Sparling 19 Toronto – Gary Smith 20 Paris – Leigh Witchel 40 Joel Lobenthal 24 A Conversation with Cynthia Gregory Joseph Houseal 40 Lady Aoi in New York Elizabeth Souritz 48 Balanchine in Russia 61 Daniel Gesmer Ballet Review 39.1 56 A Conversation with Spring 2011 Bruce Sansom Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Sandra Genter 61 Next Wave 2010 Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Michael Porter Senior Editor: Don Daniels 68 Swan Lake II Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Darrell Wilkins 48 70 Cherkaoui and Waltz Associate Editor: Larry Kaplan Joseph Houseal Copy Editor: 76 A Conversation with Barbara Palfy Mark Morris Photographers: Tom Brazil Costas 87 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Associates: Peter Anastos 100 Check It Out Robert Greskovic George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall 70 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Supon David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock CoverphotobyTomBrazil: MarkMorris’FestivalDance. Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. (Photos: Tom Brazil) 76 ballet review A Conversation with – Plato and Satie – was a very white piece. Morris: I’m postracial. Mark Morris BR: I like white. I’m not against white. Morris:Famouslyornotfamously,Satiesaid that he wanted that piece of music to be as Joseph Houseal “white as classical antiquity,”not knowing, of course, that the Parthenon was painted or- BR: My first question is . -

Oral History Interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23

Oral history interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Walker Evans conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The interview took place at the home of Walker Evans in Connecticut on October 13, 1971 and in his apartment in New York City on December 23, 1971. Interview PAUL CUMMINGS: It’s October 13, 1971 – Paul Cummings talking to Walker Evans at his home in Connecticut with all the beautiful trees and leaves around today. It’s gorgeous here. You were born in Kenilworth, Illinois – right? WALKER EVANS: Not at all. St. Louis. There’s a big difference. Though in St. Louis it was just babyhood, so really it amounts to the same thing. PAUL CUMMINGS: St. Louis, Missouri. WALKER EVANS: I think I must have been two years old when we left St. Louis; I was a baby and therefore knew nothing. PAUL CUMMINGS: You moved to Illinois. Do you know why your family moved at that point? WALKER EVANS: Sure. Business. There was an opening in an advertising agency called Lord & Thomas, a very famous one. I think Lasker was head of it. Business was just starting then, that is, advertising was just becoming an American profession I suppose you would call it. Anyway, it was very naïve and not at all corrupt the way it became later. -

An Early American Sleeping Beauty from Ballet Review Summer 2015

Summer 2015 Ball et Review An Early American Sleeping Beauty from Ballet Review Summer 2015 CoverphotographbyCostas:WendyWhelanandNikolajHübbe inBalanchine’sLaSonnambula . © 2015 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Brooklyn – Susanna Sloat 5 Berlin – Darrell Wilkins 7 London – Leigh Witchel 9 New York – Susanna Sloat 10 Toronto – Gary Smith 12 New York – Karen Greenspan 14 London – David Mead 15 New York – Susanna Sloat 16 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 19 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 21 New York – Harris Green 39 22 San Francisco – Rachel Howard 23 London – Leigh Witchel Ballet Review 43.2 24 Brooklyn – Darrell Wilkins Summer 2015 26 El Paso – Karen Greenspan Editor and Designer: 31 San Francisco – Rachel Howard Marvin Hoshino 32 Chicago – Joseph Houseal Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Sharon Skeel 34 Early American Annals of Senior Editor: Don Daniels The Sleeping Beauty Associate Editor: 54 Christopher Caines Joel Lobenthal 39 Tharp and Tudor for a Associate Editor: New Generation Larry Kaplan Michael Langlois Webmaster: 46 A Conversation with Ohad Naharin David S. Weiss Copy Editors: Leigh Witchel Barbara Palf y* 54 Ashton Celebrated Naomi Mindlin Joel Lobenthal Photographers: Tom Brazil 62 62 A Conversation with Nora White Costas Nina Alovert Associates: 70 The Mikhailovsky Ballet Peter Anastos Robert Greskovic David Mead George Jackson 76 A Conversation with Peter Wright Elizabeth Kendall Paul Parish James Sutton Nancy Reynolds 89 Indianapolis Evening of Stars James SuZon David Vaughan Leigh Witchel Edward Willinger 70 94 La Sylphide Sarah C. Woodcock Jay Rogoff 98 A Conversation with Wendy Whelan 106 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 110 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photograph by Costas: Wendy Whelan 116 Check It Out and Nikolaj Hübbe in La Sonnambula . -

1 1 December 2009 DRAFT Jonathan Petropoulos Bridges from the Reich: the Importance of Émigré Art Dealers As Reflecte

Working Paper--Draft 1 December 2009 DRAFT Jonathan Petropoulos Bridges from the Reich: The Importance of Émigré Art Dealers as Reflected in the Case Studies Of Curt Valentin and Otto Kallir-Nirenstein Please permit me to begin with some reflections on my own work on art plunderers in the Third Reich. Back in 1995, I wrote an article about Kajetan Mühlmann titled, “The Importance of the Second Rank.” 1 In this article, I argued that while earlier scholars had completed the pioneering work on the major Nazi leaders, it was now the particular task of our generation to examine the careers of the figures who implemented the regime’s criminal policies. I detailed how in the realm of art plundering, many of the Handlanger had evaded meaningful justice, and how Datenschutz and archival laws in Europe and the United States had prevented historians from reaching a true understanding of these second-rank figures: their roles in the looting bureaucracy, their precise operational strategies, and perhaps most interestingly, their complex motivations. While we have made significant progress with this project in the past decade (and the Austrians, in particular deserve great credit for the research and restitution work accomplished since the 1998 Austrian Restitution Law), there is still much that we do not know. Many American museums still keep their curatorial files closed—despite protestations from researchers (myself included)—and there are records in European archives that are still not accessible.2 In light of the recent international conference on Holocaust-era cultural property in Prague and the resulting Terezin Declaration, as well as the Obama Administration’s appointment of Stuart Eizenstat as the point person regarding these issues, I am cautiously optimistic. -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by