Redalyc.Open Source Philosophy and the Dawn of Aviation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS – 204 Charles Lewis Aviation Collection

MS – 204 Charles Lewis Aviation Collection Wright State University Special Collections and Archives Container Listing Sub-collection A: Airplanes Series 1: Evolution of the Airplane Box File Description 1 1 Evolution of Aeroplane I 2 Evolution of Aeroplane II 3 Evolution of Aeroplane III 4 Evolution of Aeroplane IV 5 Evolution of Aeroplane V 6 Evolution of Aeroplane VI 7 Evolution of Aeroplane VII 8 Missing Series 2: Pre-1914 Airplanes Sub-series 1: Drawings 9 Aeroplanes 10 The Aerial Postman – Auckland, New Zealand 11 Aeroplane and Storm 12 Airliner of the Future Sub-series 2: Planes and Pilots 13 Wright Aeroplane at LeMans 14 Wright Aeroplane at Rheims 15 Wilbur Wright at the Controls 16 Wright Aeroplane in Flight 17 Missing 18 Farman Airplane 19 Farman Airplane 20 Antoinette Aeroplane 21 Bleriot and His Monoplane 22 Bleriot Crossing the Channel 23 Bleriot Airplane 24 Cody, Deperdussin, and Hanriot Planes 25 Valentine’s Aeroplane 26 Missing 27 Valentine and His Aeroplane 28 Valentine and His Aeroplane 29 Caudron Biplane 30 BE Biplane 31 Latham Monoplane at Sangette Series 3: World War I Sub-series 1: Aerial Combat (Drawings) Box File Description 1 31a Moraine-Saulnier 31b 94th Aero Squadron – Nieuport 28 – 2nd Lt. Alan F. Winslow 31c Fraser Pigeon 31d Nieuports – Various Models – Probably at Issoudoun, France – Training 31e 94th Aero Squadron – Nieuport – Lt. Douglas Campbell 31f Nieuport 27 - Servicing 31g Nieuport 17 After Hit by Anti-Aircraft 31h 95th Aero Squadron – Nieuport 28 – Raoul Lufbery 32 Duel in the Air 33 Allied Aircraft -

Lighter-Than-Air Vehicles for Civilian and Military Applications

Lighter-than-Air Vehicles for Civilian and Military Applications From the world leaders in the manufacture of aerostats, airships, air cell structures, gas balloons & tethered balloons Aerostats Parachute Training Balloons Airships Nose Docking and PARACHUTE TRAINING BALLOONS Mooring Mast System The airborne Parachute Training Balloon system (PTB) is used to give preliminary training in static line parachute jumping. For this purpose, an Instructor and a number of trainees are carried to the operational height in a balloon car, the winch is stopped, and when certain conditions are satisfied, the trainees are dispatched and make their parachute descent from the balloon car. GA-22 Airship Fully Autonomous AIRSHIPS An airship or dirigible is a type of aerostat or “lighter-than-air aircraft” that can be steered and propelled through the air using rudders and propellers or other thrust mechanisms. Unlike aerodynamic aircraft such as fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, which produce lift by moving a wing through the air, aerostatic aircraft, and unlike hot air balloons, stay aloft by filling a large cavity with a AEROSTATS lifting gas. The main types of airship are non rigid (blimps), semi-rigid and rigid. Non rigid Aerostats are a cost effective and efficient way to raise a payload to a required altitude. airships use a pressure level in excess of the surrounding air pressure to retain Also known as a blimp or kite aerostat, aerostats have been in use since the early 19th century their shape during flight. Unlike the rigid design, the non-rigid airship’s gas for a variety of observation purposes. -

A Short History of the Royal Aeronautical Society

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE ROYAL AERONAUTICAL SOCIETY Royal Aeronautical Society Council Dinner at the Science Museum on 26 May 1932 with Guest of Honour Miss Amelia Earhart. Edited by Chris Male MRAeS Royal Aeronautical Society www.aerosociety.com Afterburner Society News RAeS 150th ANNIVERSARY www.aerosociety.com/150 The Royal Aeronautical Society: Part 1 – The early years The Beginning “At a meeting held at Argyll Lodge, Campden Hill, Right: The first Aeronautical on 12 January 1866, His Grace The Duke of Argyll Exhibition, Crystal Palace, 1868, showing the presiding; also present Mr James Glaisher, Dr Hugh Stringfellow Triplane model W. Diamond, Mr F.H. Wenham, Mr James Wm. Butler and other exhibits. No fewer and Mr F.W. Brearey. Mr Glaisher read the following than 77 exhibits were address: collected together, including ‘The first application of the Balloon as a means of engines, lighter- and heavier- than-air models, kites and ascending into the upper regions of the plans of projected machines. atmosphere has been almost within the recollection A special Juror’s Report on on ‘Aerial locomotion and the laws by which heavy of men now living but with the exception of some the exhibits was issued. bodies impelled through air are sustained’. of the early experimenters it has scarcely occupied Below: Frederick W Brearey, Wenham’s lecture is now one of the aeronautical Secretary of the the attention of scientific men, nor has the subject of Aeronautical Society of Great classics and was the beginning of the pattern of aeronautics been properly recognised as a distinct Britain, 1866-1896. -

Airwork Limited

AN APPRECIATION The Council of the Royal Aeronautical Society wish to thank those Companies who, by their generous co-operation, have done so much to help in the production of the Journal ACCLES & POLLOCK LIMITED AIRWORK LIMITED _5£ f» g AIRWORK LIMITED AEROPLANE & MOTOR ALUMINIUM ALVIS LIMITED CASTINGS LTD. ALUMINIUM CASTINGS ^-^rr AIRCRAFT MATERIALS LIMITED ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY MOTORS LTD. STRUCTURAL MATERIALS ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY and COMPONENTS AIRSPEED LIMITED SIR W. G. ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH AIRCRAFT LTD. SIR W. G. ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH AIRCRAFT LIMITED AUSTER AIRCRAFT LIMITED BLACKBURN AIRCRAFT LTD. ^%N AUSTER Blackburn I AIRCRAFT I AUTOMOTIVE PRODUCTS COMPANY LTD. JAMES BOOTH & COMPANY LTD. (H1GH PRECISION! HYDRAULICS a;) I DURALUMIN LJOC kneed *(6>S'f*ir> tttaot • AVIMO LIMITED BOULTON PAUL AIRCRAFT L"TD. OPTICAL - MECHANICAL - ELECTRICAL INSTRUMENTS AERONAUTICAL EQUIPMENT BAKELITE LIMITED BRAKE LININGS LIMITED BAKELITE d> PLASTICS KEGD. TEAM MARKS ilMilNIICI1TIIH I BRAKE AND CLUTCH LININGS T. M. BIRKETT & SONS LTD. THE BRISTOL AEROPLANE CO., LTD. NON-FERROUS CASTINGS AND MACHINED PARTS HANLEY - - STAFFS THE BRITISH ALUMINIUM CO., LTD. BRITISH WIRE PRODUCTS LTD. THE BRITISH AVIATION INSURANCE CO. LTD. BROOM & WADE LTD. iy:i:M.mnr*jy BRITISH AVIATION SERVICES LTD. BRITISH INSULATED CALLENDER'S CABLES LTD. BROWN BROTHERS (AIRCRAFT) LTD. SMS^MMM BRITISH OVERSEAS AIRWAYS CORPORATION BUTLERS LIMITED AUTOMOBILE, AIRCRAFT AND MARITIME LAMPS BOM SEARCHLICHTS AND MOTOR ACCESSORIES BRITISH THOMSON-HOUSTON CO., THE CHLORIDE ELECTRICAL STORAGE CO. LTD. LIMITED (THE) Hxtie AIRCRAFT BATTERIES! Magnetos and Electrical Equipment COOPER & CO. (B'HAM) LTD. DUNFORD & ELLIOTT (SHEFFIELD) LTD. COOPERS I IDBSHU l Bala i IIIIKTI A. C. COSSOR LIMITED DUNLOP RUBBER CO., LTD. -

1908-1909 : La Véritable Naissance De L'aviation

1908-1909 : LA VÉRITABLE 05 Histoire et culture NAISSANCE DE L’AVIATION. de l’aéronautique et du spatial A) Les démonstrations en France de Farman et des frères Wright. A la veille de 1908, ballons et dirigeables dominent encore le ciel, malgré les succès prometteurs des frères Wright, de Santos Dumont et de Vuia. A Issy-les-Moulineaux, le 13 janvier 1908, Farman réussit officiellement le premier vol contrôlé en circuit fermé d’un kilomètre à bord d’un Voisin et remporte les 50 000 francs promis par Archdeacon et Deutsch de la Meurthe. Farman effectue ensuite le premier vol de ville à ville, entre Bouy et Reims, soit 27 km. En tournée aux Etats-Unis, il invente le mot “aileron” : il baptise ainsi les volets en bout d'aile d'avions qui sont présentés. Le premier passager de l'histoire de l'aviation serait Ernest Archdeacon qui embarque avec Henri Farman à Gand (Belgique). En août 1908, les frères Wright s’installent en France pour vendre leur « Flyer » sous licence. Le 31 décembre, Wilbur remporte les 20 000 francs du prix Michelin pour avoir effectué le plus long vol de l’année au camp d’Auvours : 124,7 km en 2h20. Les Wright voulaient garder secret leur système de gauchissement des ailes (torsion du bout des ailes pour incliner de côté un avion) au point de dormir à côté de l’avion. Les Américains fondent la première école de pilotage au monde à Pau. Aux Etats-Unis, le Wright Flyer III, piloté par Orville Wright, est victime d'un accident à la suite de la rupture d'une des hélices en plein vol. -

Flânerie Au Cœur Du Quartier Coteaux/Bords De Seine

Flânerie au cœur du quartier COTEAUX/BORDS DE SEINE 2km 1h30 www.saintcloud.fr Flânerie au cœur du quartier COTEAUX/BORDS DE SEINE Fière de son histoire et de son patrimoine, seuses au XIXe siècle. Le quai Carnot était la municipalité de Saint-Cloud vous invite également investi d’hôtels et restaurants à flâner dans les rues de la commune en qui accueillaient les Parisiens venus profi- publiant cinq livrets qui vous feront décou- ter des distractions organisées dans le parc vrir le patrimoine historique, artistique et de Saint-Cloud. Ce quartier devient plus architectural des différents quartiers de résidentiel au début du XXe siècle lorsque la Saint-Cloud. Le passionné de patrimoine Société foncière des Coteaux et du bois de ou l’amateur de belles promenades pourra Boulogne acquiert les terrains situés entre cheminer, de manière autonome, à l’aide les deux voies de chemin de fer. de ce dépliant, en suivant les points numé- rotés sur le plan (au verso) qui indique les Parcours de 2 kilomètres lieux emblématiques de la ville. Durée : environ 1h30 Partez à la découverte des vestiges, des En savoir plus sites classés ou remarquables qui vous Musée des Avelines, musée d’art révèleront la richesse de Saint-Cloud. Son et d’histoire de Saint-Cloud histoire commence il y a plus de 2000 ans 60, rue Gounod lorsque la ville n’était encore qu’une simple 92210 Saint-Cloud PARUTION JUILLET 2017 bourgade gallo-romaine appelée Novigen- 01 46 02 67 18 www.musee-saintcloud.fr tum. Entrée libre Le quartier des Coteaux, autrefois agricole, du mercredi au samedi de 12h à 18h vivait de la culture de la vigne tandis que Dimanche de 14h à 18h les bords de Seine étaient plutôt réservés Le musée organise des visites guidées à l’activité des pêcheurs puis des blanchis- de la ville. -

1914/1918 : Nos Anciens Et Le Développement De L' Aviation

1914/1918 : Nos Anciens et le Développement de l’aviation militaire René Couillandre, Jean-Louis Eytier, Philippe Jung 06 novembre 2018 - 18h00 Talence 1914/1918 : Nos Anciens et le développement de l’ aviation militaire Chers Alumnis, chers Amis, Merci d’être venus nombreux participer au devoir de mémoire que toute Amicale doit à ses diplômés. Comme toute la société française en 1914, les GADZARTS, à l’histoire déjà prestigieuse, et SUPAERO, née en 1909, ont été frappés par le 1er conflit mondial. Les jeunes diplômés, comme bien d’autres ont été mobilisés pour répondre aux exigences nationales. Le conflit que tous croyaient de courte durée s’est révélé dévoreur d’hommes : toute intelligence, toute énergie, toute compétence fut mise au service de la guerre. L’aviation naissante, forte de ses avancées spectaculaires s’est d’abord révélé un service utile aux armes. Elle a rapidement évolué au point de devenir indispensable sur le champ de bataille et bien au-delà, puis de s’imposer comme une composante essentielle du conflit. Aujourd’hui, au centenaire de ce meurtrier conflit, nous souhaitons rendre hommage à nos Anciens qui, avec tant d’autres, de façon anonyme ou avec éclat ont permis l’évolution exceptionnelle de l’aviation militaire. Rendre hommage à chacun est impossible ; les célébrer collectivement, reconnaître leurs sacrifices et leurs mérites c’est nourrir les racines de notre aéronautique moderne. Nous vous proposons pour cela, après un rappel sur l’ aviation en 1913, d’effectuer un premier parcours sur le destin tragique de quelques camarades morts au champ d’honneur ou en service aérien en les resituant dans leur environnement aéronautique ; puis lors d’un second parcours, de considérer la présence et l’apport d’autres diplômés à l’évolution scientifique, technique, industrielle ou opérationnelle de l’ aviation au cours de ces 4 années. -

Airborne Arctic Weather Ships Is Almost Certain to Be Controversial

J. Gordon Vaeth airborne Arctic National Weather Satellite Center U. S. Weather Bureau weather ships Washington, D. C. Historical background In the mid-1920's Norway's Fridtjof Nansen organized an international association called Aeroarctic. As its name implies, its purpose was the scientific exploration of the north polar regions by aircraft, particularly by airship. When Nansen died in 1930 Dr. Hugo Eckener of Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin Company suc- ceeded him to the Aeroarctic presidency. He placed his airship, the Graf Zeppelin, at the disposal of the organization and the following year carried out a three-day flight over and along the shores of the Arctic Ocean. The roster of scientists who made this 1931 flight, which originated in Leningrad, in- cluded meteorologists and geographers from the United States, the Soviet Union, Sweden, and, of course, Germany. One of them was Professor Moltschanoff who would launch three of his early radiosondes from the dirigible before the expedition was over. During a trip which was completed without incident and which included a water land- ing off Franz Josef Land to rendezvous with the Soviet icebreaker Malygin, considerable new information on Arctic weather and geography was obtained. Means for Arctic More than thirty years have since elapsed. Overflight of Arctic waters is no longer his- weather observations toric or even newsworthy. Yet weather in the Polar Basin remains fragmentarily ob- served, known, and understood. To remedy this situation, the following are being actively proposed for widespread Arctic use: Automatic observing and reporting stations, similar to the isotopic-powered U. S. Weather Bureau station located in the Canadian Arctic. -

Langley Experiments Scrapbooks

Langley Experiments Scrapbooks 2001 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Langley Experiments Scrapbooks NASM.XXXX.0294 Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: Langley Experiments Scrapbooks Identifier: NASM.XXXX.0294 Date: 1914-1915 Creator: Curtiss, Glenn Hammond, 1878-1930 Extent: 0.23 Cubic feet ((1 slim legal box)) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Glenn H. Curtiss, gift, unknown, XXXX-0294, NASM Restrictions No restrictions on access Conditions Governing Use Material is subject to Smithsonian Terms of Use. Should you wish to use NASM material in any medium, please submit an Application -

A Brief History of Aviation-Part I with Emphasis on American Aviation Faster, Higher, Further!

A Brief History of Aviation-Part I With Emphasis on American Aviation Faster, Higher, Further! OLLI Fall 2012 Session L805 Mark Weinstein, Presenter 1 Full Disclosure • Currently a Docent at both Smithsonian Air and Space Museums • Retired from the Air Force-Active duty and Reserve • Electrical Engineer • 104 hours flying a Piper Tri-Pacer Wanted Caution: Long Winded Stories Reward: Info and Enjoyment 2 Ask Questions ― ? As we fly along ? 3 Anyone here a Pilot? 4 Historical Perspective • Historians and economists consider Aviation and follow on Space Endeavors to be one on the key transitional events of the 20 th Century. Aviation is more than the sum of it parts and it drove and was driven by: – Expanding technologies – Aeronautical engineering and research – Advance in manufacturing – Industrial development and national industrial policies – New materials – Warfare needs and drivers – Political actions – Transportation needs, investments and subsidies – Large scale population migration – Adventure, exploration, vision and finally fantasy. 5 Starting Off on a Positive Note • "Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible“ -- Lord Kelvin, President, Royal Society, 1895. • "Airplanes are interesting toys but of no military value“ -- Marshal Ferdinand Foch, Professor of Strategy, Ecole Superieure de Guerre, France, 1911 -- Commander of all Allied Forces, 1918 • "Everything that can be invented has been invented" -- Charles H. Duell, Commissioner, US Office of Patents, 1899. 6 Session Subjects More or less – Part I 7 Session Subjects – Part II More or less 8 Pre WB- WWI WWII WWII K/V ME ME 1911 1911- 1919- 1938- 1942- 1946- 1981- 2001- 1918 1937 1941 1945 1980 2000 2012 Early Aviation 1909 WB-F WW I Europeans US Growth and Expansion WW II B of B Pearl Harbor Eur. -

The Voisin Biplane by Robert G

THE VOISIN BIPLANE BY ROBERT G. WALDVOGEL A single glance at the Voisin Biplane reveals exactly what one would expect of a vintage aircraft: a somewhat ungainly design with dual, fabric-covered wings; a propeller; an aerodynamic surface protruding ahead of its airframe; and a boxy, kite-resembling tail. But, by 1907 standards, it had been considered “advanced.” Its designer, Gabriel Voisin, son of a provincial engineer, was born in Belleville, France, in 1880, initially demonstrating mechanical and aeronautical aptitude through his boat, automobile, and kite interests. An admirer of Clement Ader, he trained as an architect and draftsman at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, and was later introduced to Ernest Archdeacon, a wealthy lawyer and aviation enthusiast, who subsequently commissioned him to design a glider. Using inaccurate and incomplete drawings of the Wright Brothers’ 1902 glider published in L’Aerophile, the Aero-Club’s journal, Voisin constructed an airframe in January of 1904 which only bore a superficial resemblance to its original. Sporting dual wings subdivided by vertical partitions, a forward elevating plane, and a two-cell box-kite tail, it was devoid of the Wright-devised wing- warping method, and therefore had no means by which lateral control could be exerted. Two-thirds the size of the original, it was 40 pounds lighter. Supported by floats and tethered to a Panhard-engined racing boat, the glider attempted its first fight from the Seine River on June 8, 1905, as described by Voisin himself. “Gradually and cautiously, (the helmsman) took up the slack of my towing cable…” he had written. -

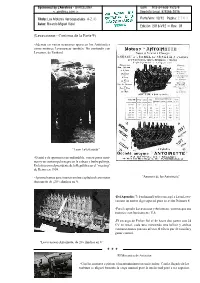

Levavasseur.- Continua De La Parte 9

Sponsored by L’Aeroteca - BARCELONA ISBN 978-84-608-7523-9 < aeroteca.com > Depósito Legal B 9066-2016 Título: Los Motores Aeroespaciales A-Z. © Parte/Vers: 10/12 Página: 2701 Autor: Ricardo Miguel Vidal Edición 2018-V12 = Rev. 01 (Levavasseur.- Continua de la Parte 9) -Además en varias ocasiones aparecen los Antoinettes como motores Levavasseur también. No confundir con Levassor, de Panhard. “Leon Levavasseur” -Genial y de apariencia inconfundible, con su gorra mari- nera y un curioso pelo negro en la cabeza y barba peliroja. En la foto con el presidente de la República en el “meeting” de Reims en 1909. -Aprovechamos para insertar en éste capítulo el raro motor “Anuncio de los Antoinette” Antoinette de ¡20! cilindros en V. -Del Apendice 7: Ferdinand Ferber encargó a Leon Leva- vasseur un motor algo especial para su avión Número 8. -Por el capitulo Levavasseur y Antoinette, vemnos que sus motores eran basicamente V-8. -El encargo de Ferber fué el de hacer dos partes con 24 CV en total, cada una moviendo una hélice y ambas contrarotatorias para no afectar el efecto par de torsión y ganar control. “Levavasseur-Antoinette, de 20 cilindros en V” * * * El Mecanico de Aviación -Con los motores a piston, el mantenimiento era más arduo. Con la llegada de las turbinas se aligeró bastante la carga manual pero la intelectual pasó a ser superior. Sponsored by L’Aeroteca - BARCELONA ISBN 978-84-608-7523-9 Este facsímil es < aeroteca.com > Depósito Legal B 9066-2016 ORIGINAL si la Título: Los Motores Aeroespaciales A-Z. © página anterior tiene Parte/Vers: 10/12 Página: 2702 el sello con tinta Autor: Ricardo Miguel Vidal VERDE Edición: 2018-V12 = Rev.