La Dolce Vita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Cinema As Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr

ENGL 2090: Italian Cinema as Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr. Lisa Verner [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course surveys Italian cinema during the postwar period, charting the rise and fall of neorealism after the fall of Mussolini. Neorealism was a response to an existential crisis after World War II, and neorealist films featured stories of the lower classes, the poor, and the oppressed and their material and ethical struggles. After the fall of Mussolini’s state sponsored film industry, filmmakers filled the cinematic void with depictions of real life and questions about Italian morality, both during and after the war. This class will chart the rise of neorealism and its later decline, to be replaced by films concerned with individual, as opposed to national or class-based, struggles. We will consider the films in their historical contexts as literary art forms. REQUIRED TEXTS: Rome, Open City, director Roberto Rossellini (1945) La Dolce Vita, director Federico Fellini (1960) Cinema Paradiso, director Giuseppe Tornatore (1988) Life is Beautiful, director Roberto Benigni (1997) Various articles for which the instructor will supply either a link or a copy in an email attachment LEARNING OUTCOMES: At the completion of this course, students will be able to 1-understand the relationship between Italian post-war cultural developments and the evolution of cinema during the latter part of the 20th century; 2-analyze film as a form of literary expression; 3-compose critical and analytical papers that explore film as a literary, artistic, social and historical construct. GRADES: This course will require weekly short papers (3-4 pages, double spaced, 12- point font); each @ 20% of final grade) and a final exam (20% of final grade). -

La Dolce Vita Actress Anita Ekberg Dies at 83

La Dolce Vita actress Anita Ekberg dies at 83 Posted by TBN_Staff On 01/12/2015 (29 September 1931 – 11 January 2015) Kerstin Anita Marianne Ekberg was a Swedish actress, model, and sex symbol, active primarily in Italy. She is best known for her role as Sylvia in the Federico Fellini film La Dolce Vita (1960), which features a scene of her cavorting in Rome's Trevi Fountain alongside Marcello Mastroianni. Both of Ekberg's marriages were to actors. She was wed to Anthony Steel from 1956 until their divorce in 1959 and to Rik Van Nutter from 1963 until their divorce in 1975. In one interview, she said she wished she had a child, but stated the opposite on another occasion. Ekberg was often outspoken in interviews, e.g., naming famous people she couldn’t bear. She was also frequently quoted as saying that it was Fellini who owed his success to her, not the other way around: "They would like to keep up the story that Fellini made me famous, Fellini discovered me", she said in a 1999 interview with The New York Times. Ekberg did not live in Sweden after the early 1950s and rarely visited the country. However, she welcomed Swedish journalists into her house outside Rome and in 2005 appeared on the popular radio program Sommar, and talked about her life. She stated in an interview that she would not move back to Sweden before her death since she would be buried there. On 19 July 2009, she was admitted to the San Giovanni Hospital in Rome after falling ill in her home in Genzano according to a medical official in the hospital's neurosurgery department. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

The Odyssey of Fellini Kayla Knuth

ISSUE #1 | JULY 2020 The Odyssey of Fellini Kayla Knuth Making raw cinematic artistry work on the big screen can be extremely challenging, and directors such as Federico Fellini meet that challenge by giving us unique films, each with a clear vision. There are many masterful auteurs within the film industry, but there is something about Fellini’s good-natured style that truly engages me, along with how he incorporates elements of both reality and fantasy in iconic films such as La Strada (1953), La Dolce Vita (1961), and 8 ½ (1963). Not everyone is capable of digging deeper into what the artist is actually saying, and many are too quick to make harsh judgements about what they see rather than what they interpret. This is another reason why his film work interests me. I enjoy the “chase” that helps me provide a deeper analysis of what certain scenes in his films actually symbolize. This makes me pay closer attention to the films, and I find myself rewinding scenes, taking a step back to investigate the meaning of what I’m seeing. Almost all of Fellini’s films feature a dominant protagonist character with qualities to which the audience can at least secretly relate. Some of Fellini’s most striking cinematic moments are memorable because of characters that tend to stick with you even when the films become unclear at times. In addition, the artistry, passion, zest for life, and inven- tiveness on display in his filmmaking help us appreciate a wide range of possibilities for cinematic representation. Aesthetically, Fellini’s films reach for what I will call “ugliness within beauty.” His films seem to ask: is there beauty to be found within ugliness? Or is there ugliness lurking within the beautiful? Fellini attempts to ask these questions through both his striking visuals and sympathetic characters. -

Un Grand Film : La Strada

LES ECHOS DE SAINT-MAURICE Edition numérique Raphaël BERRA Un grand film : La Strada Dans Echos de Saint-Maurice, 1961, tome 59, p. 277-284 © Abbaye de Saint-Maurice 2012 UN GRAND FILM La Strada « Au terme de nos recherches, il y a Dieu. » FELLINI NOTES SUR L'AUTEUR ET SUR SON ŒUVRE Federico Fellini naît le 20 janvier 1920 à Rimini, station balnéaire des bords de l'Adriatique. Son enfance s'écoule entre le collège des Pères, à Fano, et les vacances à la campagne, à Gambettola, où passent fréquemment les gitans et les forains. Toute l'œuvre de Fellini sera mar quée par le souvenir des gens du voyage, clowns, équi libristes et jongleurs ; par le rythme d'une ville, aussi, où les étés ruisselant du luxe des baigneurs en vacances alternaient avec les hivers mornes et gris, balayés par le vent glacial. Déjà au temps de ses études, Fellini avait manifesté un goût très vif pour la caricature, et ses dessins humo ristiques faisaient la joie de ses camarades. Ce talent l'introduit chez un éditeur de Florence, puis à Rome, où il se rend en 1939. La guerre survient. Sans ressources, Fellini vit d'expédients avant d'ouvrir cinq boutiques de caricatures pour soldats américains. C'est cette période de sa vie qui fera dire à Geneviève Agel (dans une étude remarquable intitulée « Les chemins de Fellini ») : « C'est peut-être à force de caricaturer le visage des hommes qu'il est devenu ce troublant arracheur de masques ». En 1943, Fellini épouse Giulietta Masina. Puis il ren contre Roberto Rossellini qui lui fait tenir le rôle du vagabond dans son film LE MIRACLE. -

Course Content. All Students Agreed That the Proposed Objectives Had

DOC1'MFvT RPqlMF ED 021 546 JC 680 292 By- Cawthon, David L. OKLAHOMA CONSORTIUM ON RESEARCH DEVELOPMENT PILOTGRANT INTRODUCTION TO FILM. FINAL REPORT. Pub Date 68 Note-10p. EDRS Price MF-10.25 HC- W.48 Descriptors- AUDIOVISUAL AIDS, *COLLEGE CURRICULUM.COURSE EVALUATION. *EDUCATIONAL INNOVATION *EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES FILM PRODUCTION, *FILMS,INNOVATION INSTRUCTIONAL INNOVATION *JUNIOR COLLEGES, STUDENT OPINION, STUDENT REACTION Identifiers-*Oklahoma, Shawnee Although educators have beenturning to motion pictures and televisionas devices for supplementing instruction, therehas been a sparsity of instruction about the elements of filmor how to understand the medium. An innovativeprogram designed to meet this need was introduced at St. Gregory's College.The course dealt with the history and thegrammar of the medium, the film in relation to other art forms, and the film as an artistic estheticexperience. Methods of instruction included lectures, screening of films, discussions ingroups and as an entire class, and reading and summarizing film reviews. The class met three hoursa week for 16 weeks. Projects were the preparation of portfolios containing critic and student filmreviews or the preparation of a 5- to 10-minute filmgrammar and technique. At the conclusion of the course, the 42 students were asked to evaluate the objectives, filmselections, and course content.Allstudents agreed thatthe proposed objectives had been accomplished. With fewexceptions, the students agreed that the films screened adequately represented the academicarea under study. As a result of the evaluation it was decided that (1) the attemptto offer a comparative study of the filmin relation to other art forms should be eliminated, (2)the order in which the materialwas presented should be altered, and (3)more concentration should be given to the era of the 1930's. -

Federico Fellini and the Experience of the Grotesque and Carnavalesque – Dis-Covering the Magic of Mass Culture 2013

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Annie van den Oever Federico Fellini and the experience of the grotesque and carnavalesque – Dis-covering the magic of mass culture 2013 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15114 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: van den Oever, Annie: Federico Fellini and the experience of the grotesque and carnavalesque – Dis-covering the magic of mass culture. In: NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, Jg. 2 (2013), Nr. 2, S. 606– 615. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15114. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.5117/NECSUS2013.2.VAND Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 NECSUS – EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES About the author Francesco Di Chiara (University of Ferrara) 2013 Di Chiara / Amsterdam University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly -

October 5, 2010 (XXI:6) Federico Fellini, 8½ (1963, 138 Min)

October 5, 2010 (XXI:6) Federico Fellini, 8½ (1963, 138 min) Directed by Federico Fellini Story by Federico Fellini & Ennio Flaiano Screenplay by Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Federico Fellini & Brunello Rondi Produced by Angelo Rizzoli Original Music by Nino Rota Cinematography by Gianni Di Venanzo Film Editing by Leo Cattozzo Production Design by Piero Gherardi Art Direction by Piero Gherardi Costume Design by Piero Gherardi and Leonor Fini Third assistant director…Lina Wertmüller Academy Awards for Best Foreign Picture, Costume Design Marcello Mastroianni...Guido Anselmi Claudia Cardinale...Claudia Anouk Aimée...Luisa Anselmi Sandra Milo...Carla Hazel Rogers...La negretta Rossella Falk...Rossella Gilda Dahlberg...La moglie del giornalista americano Barbara Steele...Gloria Morin Mario Tarchetti...L'ufficio di stampa di Claudia Madeleine Lebeau...Madeleine, l'attrice francese Mary Indovino...La telepata Caterina Boratto...La signora misteriosa Frazier Rippy...Il segretario laico Eddra Gale...La Saraghina Francesco Rigamonti...Un'amico di Luisa Guido Alberti...Pace, il produttore Giulio Paradisi...Un'amico Mario Conocchia...Conocchia, il direttore di produzione Marco Gemini...Guido da ragazzo Bruno Agostini...Bruno - il secundo segretario di produzione Giuditta Rissone...La madre di Guido Cesarino Miceli Picardi...Cesarino, l'ispettore di produzione Annibale Ninchi...Il padre di Guido Jean Rougeul...Carini, il critico cinematografico Nino Rota...Bit Part Mario Pisu...Mario Mezzabotta Yvonne Casadei...Jacqueline Bonbon FEDERICO FELLINI -

LCCC Thematic List

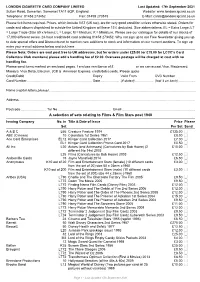

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

From 5 to 13 October at Fiere Di Parma

Press Release MERCANTEINFIERA AUTUMN THE POETRY OF THE HEEL, ITALIAN MASTERS OF PHOTOGRAPHY AND FOUR CENTURIES OF ART HISTORY From 5 to 13 October at Fiere di Parma Mercanteinfiera, the Fiere di Parma international exhibition of antiques, modern antiques, design and vintage collectibles, is an increasingly “fusion” event. Protagonists of the 38th edition are the Villa Foscarini Rossi Shoes Museum of the LVMH Group and the BDC Art Gallery in Parma, owned by Lucia Bonanni ad Mauro del Rio, curators of the two collateral exhibitions. On the one hand, stylists such as Dior, Kenzo, Yves Saint Laurent and Nicholas Kirkwood highlighted by the far-sightedness of the entrepreneur Luigino Rossi, the Muse- um’s founder. On the other, masters of the visual language such as Ghirri, Sottsass, Jodice, as well as the paparazzi. With Lino Nanni and Elio Sorci, we will dive into the years of the exuberant Dolce Vita. (Parma, 30 September 2019) - At the beginning there were” pianelle”, or “chopines”, worn by both aristocratic women and commoners to protect their feet from mud and dirt. They could be as high as 50 cm (but only for the richest ladies), while four centuries later Mari- lyn Monroe would build her image on a relatively very modest 11-cm peep toe heel. For Yves Saint Laurent the perfect stride required a 9-cm heel. This was too high for the Swinging Sixties of London and Twiggy, when ballerinas were the footwear of choice. Whether high, low, with a 9 or 11cm heel, shoes have always been the best-loved accesso- ry of fashion victims and many others and they are the protagonists of the collateral exhi- bition “In her Shoes. -

SAAS Conference Program (P

Celebrated, Contested, Criticized: Anita Ekberg, a Swedish Sex Goddess in Hollywood Wallengren, Ann-Kristin 2018 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wallengren, A-K. (2018). Celebrated, Contested, Criticized: Anita Ekberg, a Swedish Sex Goddess in Hollywood. 34. Abstract from The Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS), . Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 10th Biennial Conference of The Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS) OPEN COVENANTS: PASTS AND FUTURES OF GLOBAL AMERICA Friday September 28th – Sunday September 30th 2018 Stockholm, Sweden PROGRAM MAGNUS BERGVALLS STIFTELSE Welcome to the 10th biennial conference of the Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS) Stockholm, September 28–30, 2018 Keynote speakers: Prof. -

La Dolce Vita Nothing but the Best Is Good Enough for You

La Dolce Vita Nothing but the best is good enough for you La Dolce Vita Nothing but the best is good enough for you La The phrase comes from the title of a famous Federico Fellini movie, with a memorable scene in which Marcello Dolce Mastroianni bathes with alluring Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain in Rome, late at night. La dolce vita, actually, is much more than enjoying life’s most epicurean Vita and seductive joys, it is at once a community lifestyle and a state-of-mind, a way of being in the world and of the world. The expression comes from the title of a famous Federico Fellini movie. In a memorable scene, Marcello Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg take a late night dip in Rome’s Trevi fountain. In truth, “la dolce vita” is much more than enjoying life’s seductive pleasures. It is a lifestyle, a state-of-mind... La Dolce Vita “La dolce vita”… dreamily pronounced, is an iconic Italian expression. The “sweet life” conveys that relaxed, pleasure-filled lifestyle that Italians are known to seek and cultivate. This is at the heart of an unforgettable Italian vacation. Passionately devoted to this philosophy Italy’s Finest is delighted to present the ultimate Italian experience: La Dolce Vita Vacation. La Dolce Vita Beloved FAMILY, cherished FRIENDS and delicious FOOD are the indispensable values the Italians treasure. Living life to its fullest means savoring these pleasures leisurely, every day. Wishes Desires& Breathtaking natural beauty, unrivaled artistic heritage and Which are the indispensable elements in life, those lively traditions from the Alps to values that Italians pursue, treasure and bravely defend Sicily.