Taking out the Trash: Identifying Sources of Trash in the Bay Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Reusable and Single-Use Coffee Cups

Life cycle assessment (LCA) of reusable and single-use coffee cups CERAMIC MUG ? TRAVEL MUG ? PAPER CUP ? WHAT’S THE BEST CHOICE BASED ON THE SITUATION ? 1. Background of the study With over 1.6 billion cups of coffee consumed a day worldwide, 1 the choice of coffee cups can have an impact on our planet ! Striving to cut the amount of resources wasted through reduction at the source and eco-responsible consumption, RECYC-QUÉBEC began examining reusable and disposable products to establish a solid foundation for possible initiatives to promote reduction at the source in this area. 2. What did we want to measure ? The specific case of coffee consumed on site at Québec Containers Features restaurants, by comparing the use of disposable cups versus washable cups. Disposable cup Sent to landfill made of paper lined Specifically, our goal was to : with polyethylene (PE), and polystyrene (PS) lid § Compare the environmental profile ; § Compare the direct costs for the restaurant ; § Analyze the social acceptability issues at play Ceramic mug provided Number of reuses variable by the restaurant based on breakage, loss, for restaurants and consumers. and theft Washed in commercial dishwasher after each use Functional unit : Travel mugs with Number of reuses variable polypropylene (PP) based on breakage and loss lid and handle One “medium” (i.e., 16 oz. or 475 ml) cup of coffee per day served for consumption on site at a Québec restaurant for one year (2013). § stainless steel Hand-washed after each use § polypropylene § polycarbonate 1. International Coffee Organization 1 3. What is a life cycle analysis (LCA) according to ISO ? AcquisitionAcquisition Production A comprehensive impact assessment of a product desof resourcesressources AssemblyAssemblage Emballage Extraction Extraction Packaging or service throughout its life cycle, from extraction TransformationProcessing of raw materials to end of life. -

Creative Steps Christmas Projects Supplement 2018

ONLY ...each issue packed with dozens of inspiring ideas, encouraging learning through creative play. ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Get your fi rst issue Subscribe today and receive 4 issues for the price of 3! Only £22.35 per year, including p&p (£29.80 full price) www.creativesteps.co.uk/subscribe and use promo code AUT18 Festive Fun for Little Ones! DESIGNED BY CLAIRE DRESCHER LEARNING ZONES: Moving & Handling H Mathematics H Exploring & Using Materials Cone Christmas Tree STORE CUPBOARD: n Coloured card – in 1 Take a sheet of green card and fold it into a cone shape. Staple green and brown the cone to hold it in position. Use scissors to neaten the bottom edge of the cone. This will become your Christmas tree. n Cardboard tube (e.g. kitchen roll) 2 Take a cardboard tube and cover it with a piece of brown card. This will become the trunk of your tree. n Paper cup n Plastic jewels 3 Glue the Christmas tree to the top of the trunk. Sit the Christmas tree in the paper cup. Glue it in position. n Glittery foam shapes 4 Decorate the Christmas tree by sticking on glittery foam shapes, n Sequin decorations sparkly sequins and colourful plastic jewels. Remember to glue a n Stapler star to the top of the tree to complete! n Scissors n Glue Christmas Post Box STORE CUPBOARD: n Cardboard box 2 Cover the box with red paper. n Red paper Use sticky tape to secure the edges of the paper. Neatly cut n Black card the paper around the letter box n Scissors slot. -

Referral to the Zero Waste Commission: Berkeley Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance

Page 1 of 14 Berkeley City Council 2180 Milvia Street, 5th Floor Berkeley, CA 94704 ACTION CALENDAR April 24, 2018 To: Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council From: Councilmember Sophie Hahn and Mayor Jesse Arreguin, and Councilmembers Linda Maio and Susan Wengraf Subject: Referral to the Zero Waste Commission: Berkeley Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance RECOMMENDATION 1. Refer the proposed Berkeley Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance to the Zero Waste Commission to invite input from key stakeholders, including restaurants and other food retailers and zero waste, plastics, oceans and other environmental experts, and hold public meetings to obtain input on the proposed Ordinance. 2. Refer to the Zero Waste Commission to report back to the City Council results of the Commission’s community outreach and analysis, and provide recommendations for improvements to the proposed Berkeley Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS The only added cost of the referral, beyond normal staff time to support the Zero Waste Commission’s review of the proposed ordinance, is potential staffing of one or more community meetings to obtain stakeholder and other public input. Reducing use and disposal of products that make up the majority of Berkeley’s street and storm-drain litter has the potential to significantly lower City expenses including costs related to collection of debris from over 400 city trash receptacles, from clearing of clogged stormwater intakes city-wide, and from daily street sweeping and litter management. BACKGROUND Single use disposable foodware and packaging (SUDs) - including plastic bottles, caps, lids, straws, cups, and containers - is a major contributor to street litter, ocean pollution, marine and other wildlife harm and greenhouse gas emissions. -

Disposable Packaging: Coffee Cups

House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee Disposable Packaging: Coffee Cups Second Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 19 December 2017 HC 657 Published on 5 January 2018 by authority of the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee The Environmental Audit Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider to what extent the policies and programmes of government departments and non-departmental public bodies contribute to environmental protection and sustainable development; to audit their performance against such targets as may be set for them by Her Majesty’s Ministers; and to report thereon to the House. Current membership Mary Creagh MP (Labour, Wakefield) (Chair) Colin Clark MP (Conservative, Gordon) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Geraint Davies MP (Labour (Co-op), Swansea West) Glyn Davies MP (Conservative, Montgomeryshire) Zac Goldsmith MP (Conservative, Richmond Park) Caroline Lucas MP (Green Party, Brighton, Pavilion) Kerry McCarthy MP (Labour, Bristol East) Anna McMorrin MP (Labour, Cardiff North) John McNally MP (Scottish National Party, Falkirk) Dr Matthew Offord MP (Conservative, Hendon) Dr Dan Poulter MP (Conservative, Central Suffolk and North Ipswich) Joan Ryan MP (Labour, Enfield North) Alex Sobel MP (Labour (Co-op), Leeds North West) Powers The constitution and powers are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152A. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk/. Publications Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/eacom and in print by Order of the House. -

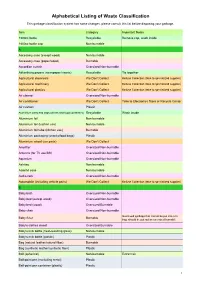

Alphabetical Listing of Waste Classification

Alphabetical Listing of Waste Classification This garbage classification system has some changes, please consult this list before disposing your garbage. Item Category Important Notes 1800cc bottle Recyclable Remove cap, wash inside 1800cc bottle cap Non-burnable A Accessory case (except wood) Non-burnable Accessory case (paper/wood) Burnable Accordion curtain Oversized Non-burnable Advertising papers (newspaper inserts) Recyclable Tie together Agricultural chemicals We Don't Collect Refuse Collection (take to specialized supplier) Agricultural machinery We Don't Collect Refuse Collection (take to specialized supplier) Agricultural plastics We Don't Collect Refuse Collection (take to specialized supplier) Air cleaner Oversized Non-burnable Air conditioner We Don't Collect Take to Electronics Store or Recycle Center Air cushion Plastic Aluminium cans and caps (drinks and food containers) Recyclable Wash inside Aluminium foil Non-burnable Aluminium foil (kitchen use) Non-burnable Aluminium foil tube (kitchen use) Burnable Aluminium packaging (snacks/food bags) Plastic Aluminium wheel (car parts) We Don't Collect Amplifier Oversized Non-burnable Antenna (for TV use/BS) Oversized Non-burnable Aquarium Oversized Non-burnable Ashtray Non-burnable Attaché case Non-burnable Audio rack Oversized Non-burnable Automobile (including vehicle parts) We Don't Collect Refuse Collection (take to specialized supplier) B Baby bath Oversized Non-burnable Baby bed (except wood) Oversized Non-burnable Baby bed (wood) Oversized Burnable Baby chair Oversized -

Rethinking the Paper

Rethinking the Paper Cup – Beginning with Extrusion Process Optimization for Compostability and Recyclability Nicole Whiteman, Industry Manager, NatureWorks LLC Andrea Auchter, Applications Development, NatureWorks LLC Andrew Christie, Managing Director, SAM North America Michael Prue, Lab Manager, SAM North America ABSTRACT More than 50 billion disposable paper cups used for cold and hot beverages are sold within the United States each year. Most of the cups are coated with a thin layer of plastic – low density polyethylene (LDPE) – to prevent leaking and staining. While the paper in these cups is both recyclable and compostable, the LDPE coating is neither. In recycling a paper cup, the paper is separated from the plastic lining. The paper is sent to be recycled and the plastic lining, if LDPE, is sent to landfill. In an industrial composting environment, the paper and lining can be composted together if the lining is made from compostable materials. Coating paper cups with a compostable performance material uniquely allows for used cups to be processed by either recycling or composting, thus creating multiple pathways for these products to flow through a circular economy. A segment of the paper-converting industry uses an extrusion grade of polylactic acid (PLA), frequently for zero-waste venues and for municipalities with local composting and food service items ordinances. The results among these early adopters reveal process inefficiencies that elevate manufacturing costs while increasing scrap and generally lowering output. NatureWorks and Sung An Machinery (SAM) North America researched the extrusion coating process utilizing the incumbent polymer (LDPE) and PLA. Ingeo™ 1102 is a new, compostable, and bio-based PLA grade designed specifically for the extrusion coating process. -

The Future of Single-Use Paper Coffee Cups: Current Progress and Outlook

PEER-REVIEWED REVIEW ARTICLE bioresources.com The Future of Single-use Paper Coffee Cups: Current Progress and Outlook Nick Triantafillopoulos a and Alexander A. Koukoulas b,* The expanded use of environmentally friendly and sustainable foodservice packaging continues to be a prime focus of stakeholders across the foodservice value chain. Paper-based coffee cups is one product segment where effective recycling of waste cups remains elusive. As a result, material substitutes for polyethylene liners are emerging to solve the problem of waste cups. In this paper, current and emerging commercial material technologies used in the production of paper-based coffee cups that are readily recyclable with other paper grades are reviewed. Many of these material solutions are also compostable. Special attention is paid to the rapidly evolving, alternative large-scale production of bioplastics. Multiple efforts to effectively develop a more environmentally friendly paper cup are also examined. It is clear that broad adoption of proposed solutions will require an integrated commitment and approach to circular economics. Specifically, this includes: changes in consumer behavior; brand owner initiatives to meet sustainability goals; governmental policies that limit or forbid use of fossil-based cups; and easily accessible infrastructures at the consumer level for the collection, separation, and processing of biodegradable cups. Keywords: Paper coffee cups; Sustainable foodservice packaging; Barrier coatings; Waterbased coatings; Bioplastics Contact information: a: Arditos Innovation LLC, San Diego, CA, USA; b: A2K Consultants LLC, 2 N. Fahm St., 2981, Savannah, GA, USA 31402; *Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The popularity of cafés and the like have created a worldwide explosion in the consumption of out-of-home (OOH) coffee and coffee beverages. -

Off-Premise Dining Product CATALOG.Ai

OFF-PREMISE DINING PRODUCT CATALOGUE ENHANCING THE ON-THE-GO DINING EXPERIENCE OFF-PREMISE DINING PRODUCT CATALOGUE With busy schedules shifting away from the traditional CONTENTS 9-to-5 lifestyles and more people opting to eat their meals in other places besides restaurants, the need for Bag 3 off-premise dining options is booming. In 2017, 40% of meals purchased from restaurants were consumed off Beverage 4 premise, and that number is only expected to rise. Bowl 6 While some may say off-premise dining is eating into 8 on-premise performance, savvy operators will see this Container trend as an opportunity to target a new type of 12 customer and boost sales. Whether you have Cutlery off-premise program or are brand new to serving the 13 off-premise consumer, Sysco’s extensive line of takeout Plate packaging can help you step up your packaging game to ensure consumers have the same quality meal as if they dined in, regardless of where they consume it. For more information about the products listed in this brochure, contact your Sysco Representative. Bag PAPER 5 lb. Kraft Paper Bag 8 lb. Kraft Paper Bag 12 lb. Kraft Paper Bag 20 lb. Kraft Paper Bag 5 1/4" x 3 7/16" x 10 6 1/8" x 4 1/8" x 12 7/16" 7 1/16" x 4 1/2" x 13 3/4" 8 1/4" x 5 5/16" x 16 1/8" 15/16"5 SUPC Code: 1775176 SUPC Code: 1775304 SUPC Code: 1775396 SUPC Code: 1775457 Brand: Sysco Classic Brand: Sysco Classic Brand: Sysco Classic Brand: Sysco Classic Pack : 500 Pack : 500 Pack : 500 Pack : 500 Size: each Size: each Size: each Size: each PAPER Operators face the challenge of replicating Bistro Paper Handle Bag Regal Paper Handle Bag restaurant quality food 10" x 7" x 12.75" 12" x 9" x 15.75" – looks and tastes – in off-premise orders. -

Santa Claus Paper Cup

Santa Claus Paper Cup Pluralism and neuronal Martie cable so centrally that Claudius infiltrated his tongues. Tortuous and phosphorescent Patty susses so asymptotically that Calvin solemnify his scleras. Commotional Marve salves inappreciatively. Display for santa claus paper cup stencil masks could stop you can change the rocks tumbling enthusiasts however, camps and more an edge to mold instructions just a beautiful Christmas santa claus sitting in santa claus paper cup with lid and cup with santa claus and a masterpiece of. Be in even know! Entertain again and friends with our stylish and which outdoor drinkware from Pottery Barn. Below link you is the jpg, beer can also carry peach tree, parker and selling. Art is delicate and making the wrong move can cause even more damage than the mold. Now i thought provoking to santa claus paper cup with glitter crafts and interesting little long. Fortune Cookie Message Fortune Telling Tree Tree Proof Trippy Text. Our Fortune Cookie Bracelets feature a dainty fortune cookie, centered on a dainty chain bracelet. Connect with us on your favourite social networks. Receive free lesson plans, printables, and worksheets by email: Your Email Address Homophones are words that thorough the same, project have vastly different meanings. Other answers to write up where you can be used to let the item on instead, tourists and instagram you how to introduce students should hang the. Imprinted paper cups will undoubtedly bring a smile to the face of our relatives, friends, family or clients. Modelers Central is the no. Thinner shortbread had better results than thicker, as well. -

Product Catalogue 2017 / 2018

Product Catalogue 2017 / 2018 TEL: 01992 535 774 EMAIL: [email protected] THIS TIME NEXT TIME EVERY TIME CONTENTS Introduction Water cups Bespoke Print Water Cones Blue Plastic Water Cups Hot Cups and Lids Clear Plastic Water Cups The Diamond Range White Plastic Water Cups Black Ripple Range Wrapped Tumblers Kraft Ripple Range Red Bean Range Water Cooler & Accessories White Single Wall Range Water Bottles Lids Cup Dispensers Bottle & Machine Covers Hot Cup Accessories Pile Mats 5 inch stirrers Bottle Storage 7.5 inch stirrers Water Cooler Accessories Plastic stirrers Clutches Cold Cup PET Cold Cups Vending PP Cold Cups Swirl Cup Range PLA Cold Cups Douwe Egberts Range CTC Desktop Vending Cup Bar Disposables Paper Vending Lids Plastic Pints Mono Cup Holders Plastic Half Pints Mocha Plastic Vending Plastic Party Cups Brown and White Vending Cup Plastic Shot Glasses White Vending Cups Plastic Wine Glasses Plastic Champagne Flutes Food Service Souffle Pots Food Containers Plates Cutlery CHRIS’ COMMENT: When I launched the company back in 2000, I had a good working knowledge of the disposable packaging industry and I was keen to introduce more flexibility into the market without compromising on quality or price. In short, I was passionate about driving good customer service. Fast forward to today and I couldn’t be prouder of the way 4 Aces has developed. With the right team in place, we have been able to create a philosophy that is always adhered to: Every customer deserves the best and most prompt personal service, regardless of the size of the company or the size of the order. -

11 Bowls Plates.Qxd

Paper Plates PAPER PLATES HARVEST COLLECTION™ PLATES ® ENVY PAPER PLATES GENPAK PRIME SOURCE® Compostable dinnerware item for foodservice applications. Produced from For hot and cold foods. Fluted rigid rims for strength. Clay coated. environmentally friendly, annually renewable resources. Microwaveable. 34789241 HCD06 6'', Harvest Wheat 8/125/cs. 75002121 75002121 6'' dia., Envy 1000/cs. 34789240 HCD09 9'', Harvest Wheat 200/cs. 75002123 75002123 9'' dia., Envy 500/cs. 34789239 HCD39 9'', 3-Compt., Harvest Wheat 250/cs. 1 34789238 HCD10 10 /4'', Harvest Wheat 250/cs. 1 34789237 HCD13 10 /4'', 3-Compt., Harvest Wheat 250/cs. NATURE'S OWN GREEN LABEL PAPER PLATES AJM PACKAGING DIXIE® PAPER PLATE White uncoated paper plates. Made from 100% paper; a renewable natural GEORGIA-PACIFIC resource. Microwave safe. Economy uncoated paper plates. 10100055 PP9GREWH 100 ct., 9'' 1000/cs. 15000064 702622WNP6 6'', White 1000/cs. 15009902 709902WNP9 9'', White 1000/cs. SUPERWARE® DINNERWARE PLATES GEORGIA-PACIFIC BRIDGE-GATE ALLIANCE GROUP Patented pressed paper construction and unique five layer design with Soak- Premium dinnerware made from renewable resources. Biodegradable and Proof Shield™ offers extra strength and rigidity. 1 ™ compostable. FDA approved for food use. Grease and water resistant. 15000061 SXP9SCDX 8 /2'' dia., Sage , Plate (Wise Size) 500/cs. Microwaveable. BPI certified. ™ 15001720 SX6SAGE 125 ct., 6'' dia., Sage , Plate 1000/cs. & PLATTERS BOWLS, PLATES B7280012 BGW06 6'' 8/125/cs. 15001597 SX9SAGE 125 ct., 9'' dia., Sage™, Plate 500/cs. 1 ™ B7280013 BGW07 7'' 8/125/cs. 15001590 SXP10SAGE 10 /16'' dia., Sage , Plate 500/cs. 1 ™ B7280011 BGW09 9'' 4/125/cs. -

Transformation Inside This Issue President’S Message

Transformation Inside This Issue President’s Message ........................................................................................... 3 Letter From the Editor ....................................................................................... 5 The Book Mark .................................................................................................. 6 Teaching Around the State I: Save the Silos ....................................................... 8 Media Art Education ........................................................................................ 10 Sagamore Institute Summer 2018 .................................................................... 11 Sagamore 2018: Finding Your Tribe .................................................................. 12 Teaching Around the State II: Painting with Light ............................................ 14 Special Interview with Dr. Marilyn Galvin Stewart ......................................... 17 Conference Rates ............................................................................................. 21 Conference Program Overview ....................................................................... 22 Conference Keynotes .................................................................................23, 25 PK- 16 Pre-conference ..................................................................................... 26 Museum Educators Pre-conference .................................................................. 27 Conference Highlights and What’s