Antarctica and Some of Its Problems Author(S): T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Region 19 Antarctica Pg.781

Appendix B – Region 19 Country and regional profiles of volcanic hazard and risk: Antarctica S.K. Brown1, R.S.J. Sparks1, K. Mee2, C. Vye-Brown2, E.Ilyinskaya2, S.F. Jenkins1, S.C. Loughlin2* 1University of Bristol, UK; 2British Geological Survey, UK, * Full contributor list available in Appendix B Full Download This download comprises the profiles for Region 19: Antarctica only. For the full report and all regions see Appendix B Full Download. Page numbers reflect position in the full report. The following countries are profiled here: Region 19 Antarctica Pg.781 Brown, S.K., Sparks, R.S.J., Mee, K., Vye-Brown, C., Ilyinskaya, E., Jenkins, S.F., and Loughlin, S.C. (2015) Country and regional profiles of volcanic hazard and risk. In: S.C. Loughlin, R.S.J. Sparks, S.K. Brown, S.F. Jenkins & C. Vye-Brown (eds) Global Volcanic Hazards and Risk, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. This profile and the data therein should not be used in place of focussed assessments and information provided by local monitoring and research institutions. Region 19: Antarctica Description Figure 19.1 The distribution of Holocene volcanoes through the Antarctica region. A zone extending 200 km beyond the region’s borders shows other volcanoes whose eruptions may directly affect Antarctica. Thirty-two Holocene volcanoes are located in Antarctica. Half of these volcanoes have no confirmed eruptions recorded during the Holocene, and therefore the activity state is uncertain. A further volcano, Mount Rittmann, is not included in this count as the most recent activity here was dated in the Pleistocene, however this is geothermally active as discussed in Herbold et al. -

Depositional Settings of the Basal López De Bertodano Formation, Maastrichtian, Antarctica

Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 62 (4): 521-529 (2007) 521 DEPOSITIONAL SETTINGS OF THE BASAL LÓPEZ DE BERTODANO FORMATION, MAASTRICHTIAN, ANTARCTICA Eduardo B. OLIVERO1, Juan J. PONCE1, Claudia A. MARSICANO2, and Daniel R. MARTINIONI1 ¹ Laboratorio de Geología Andina, CADIC-CONICET, B. Houssay 200, CC 92, 9410 Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Dpto. Cs. Geológicas, Universidad Buenos Aires, Ciudad Universitaria Pab. II, C1428 DHE Buenos Aires. ABSTRACT: In Snow Hill and Seymour islands the lower Maastrichtian, basal part of the López de Bertodano Formation, rests on a high relief, erosi- ve surface elaborated in the underlying Snow Hill Island Formation. Mudstone-dominated beds with inclined heterolithic stratification dominate the basal strata of the López de Bertodano Formation. They consist of rhythmical alternations of friable sandy- and clayey- mudstone couplets, with ripple cross lamination, mud drapes, and flaser bedding. They are characterized by a marked lenticular geometry, reflecting the filling of tide-influenced channels of various scales and paleogeographic positions within a tide-dominated embayment or estuary. Major, sand-rich channel fills, up to 50-m thick, bounded by erosive surfaces probably represent inlets, located on a more central position in the estuary. Minor channel fills, 1- to 3-m thick, associated with offlapping packages with inclined heterolithic stratification pro- bably represent the lateral accretion of point bars adjacent to migrating tidal channels in the upper estuary. Both types of channel fills bear relatively abundant marine fauna, are intensively bioturbated, and are interpreted as a network of subtidal channels. In southwestern Snow Hill Island, the minor offlapping packages have scarce marine fossils and bear aligned depressions interpreted as poor preserved dinosaur footprints. -

Of Penguins and Polar Bears Shapero Rare Books 93

OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS Shapero Rare Books 93 OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS EXPLORATION AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA +44 20 7493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com CONTENTS Antarctica 03 The Arctic 43 2 Shapero Rare Books ANTARCTIca Shapero Rare Books 3 1. AMUNDSEN, ROALD. The South Pole. An account of “Amundsen’s legendary dash to the Pole, which he reached the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912. before Scott’s ill-fated expedition by over a month. His John Murray, London, 1912. success over Scott was due to his highly disciplined dogsled teams, more accomplished skiers, a shorter distance to the A CORNERSTONE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION; THE ACCOUNT OF THE Pole, better clothing and equipment, well planned supply FIRST EXPEDITION TO REACH THE SOUTH POLE. depots on the way, fortunate weather, and a modicum of luck”(Books on Ice). A handsomely produced book containing ten full-page photographic images not found in the Norwegian original, First English edition. 2 volumes, 8vo., xxxv, [i], 392; x, 449pp., 3 folding maps, folding plan, 138 photographic illustrations on 103 plates, original maroon and all full-page images being reproduced to a higher cloth gilt, vignettes to upper covers, top edges gilt, others uncut, usual fading standard. to spine flags, an excellent fresh example. Taurus 71; Rosove 9.A1; Books on Ice 7.1. £3,750 [ref: 96754] 4 Shapero Rare Books 2. [BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION]. Grande 3. BELLINGSHAUSEN, FABIAN G. VON. The Voyage of Fete Venitienne au Parc de 6 a 11 heurs du soir en faveur de Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-1821. -

Office of Polar Programs

DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SURFACE TRAVERSE CAPABILITIES IN ANTARCTICA COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION DRAFT (15 January 2004) FINAL (30 August 2004) National Science Foundation 4201 Wilson Boulevard Arlington, Virginia 22230 DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SURFACE TRAVERSE CAPABILITIES IN ANTARCTICA FINAL COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Purpose.......................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation (CEE) Process .......................................................1-1 1.3 Document Organization .............................................................................................................1-2 2.0 BACKGROUND OF SURFACE TRAVERSES IN ANTARCTICA..................................2-1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................2-1 2.2 Re-supply Traverses...................................................................................................................2-1 2.3 Scientific Traverses and Surface-Based Surveys .......................................................................2-5 3.0 ALTERNATIVES ....................................................................................................................3-1 -

Potential Regime Shift in Decreased Sea Ice Production After the Mertz Glacier Calving

ARTICLE Received 27 Jan 2012 | Accepted 3 Apr 2012 | Published 8 May 2012 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1820 Potential regime shift in decreased sea ice production after the Mertz Glacier calving T. Tamura1,2,*, G.D. Williams2,*, A.D. Fraser2 & K.I. Ohshima3 Variability in dense shelf water formation can potentially impact Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) production, a vital component of the global climate system. In East Antarctica, the George V Land polynya system (142–150°E) is structured by the local ‘icescape’, promoting sea ice formation that is driven by the offshore wind regime. Here we present the first observations of this region after the repositioning of a large iceberg (B9B) precipitated the calving of the Mertz Glacier Tongue in 2010. Using satellite data, we find that the total sea ice production for the region in 2010 and 2011 was 144 and 134 km3, respectively, representing a 14–20% decrease from a value of 168 km3 averaged from 2000–2009. This abrupt change to the regional icescape could result in decreased polynya activity, sea ice production, and ultimately the dense shelf water export and AABW production from this region for the coming decades. 1 National Institute of Polar Research, Tachikawa, Japan. 2 Antarctic Climate & Ecosystem Cooperative Research Centre, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia. 3 Institute of Low Temperature of Science, Sapporo, Japan. *These authors contributed equally to this work. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to T.T. (email: [email protected]) or to G.D.W. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:826 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1820 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications © 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

Volcanic Activity of Mount Melbourne, Northern Victoria Land

Volcanic activity of Mount Melbourne, Present-day geothermal activity is restricted to the summit area and consists of warm ground, fumarole ice towers and northern Victoria Land pinnacles, and cave systems in snow and firn. Warm ground temperatures were measured using mercury thermometers, and ice-structure dimensions and positions were noted. The J. R. KEYS table compares maximum ground temperatures and shows that those in January 1983 were virtually identical to those in De- Antarctic Consultant cember 1972. As in 1972, the warmest temperatures in 1983 Wellington, New Zealand were associated with patches of yellow to green moss whose presence is consistent with stable heat flow (Nathan and W. C. MCINTOSH, and P. R. KYLE Schulte 1967). A constant degree of geothermal activity appears to have Department of Geoscience persisted for at least the last. 20 years. Vertical aerial pho- New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology tographs taken in 1963 show a distribution of ice structures and Socorro, New Mexico 87801 bare ground similar to that of both 1972 and 1983. Comparison of observations made in January 1983 and December 1972 indi- cates that the numbers of ice pinnacles and towers in areas I and Mount Melbourne (2,733 meters, 74° 21 S 164° 42 E) is a 3 are unchanged, but in 1983 area 2 had three or four fewer ice mildly active alkaline volcano 12 kilometers from the coast of structures. In 1983 area 1 had about 100 square meters of snow Wood Bay in northern Victoria Land. It is a predominantly and ice-free ground compared to only 40 square meters in 1972, snow- and ice-covered, low-angled strato volcano composed of whereas area 2 had less bare ground than in 1972. -

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

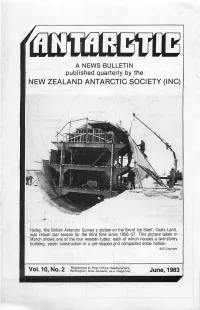

Hnitflrcitilc

HNiTflRCiTilC A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY (INC) ,m — i * Halley, the British Antarctic Survey's station on the Brunt Ice Shelf, Coats Land,, was rebuilt last season for the third time since 1956-57. This picture taken in March shows one of the four wooden tubes, each of which houses a two-storey building, under construction in a pre-shaped and compacted snow hollow. BAS Copyngh! Registered at Post Office Headquarters, Vol. 10, No. 2 Wellington, New Zealand, as a magazine. SOUTH GEORGIA -.. SOUTH SANDWICH Is «C*2K SOUTH ORKNEY Is x \ 6SignyluK //o Orcadas arg SOUTH AMERICA / /\ ^ Borga T"^00Molodezhnaya \^' 4 south , * /weooEii \ ft SA ' r-\ *r\USSR --A if SHETLAND ,J£ / / ^^Jf ORONMIIDROWNING MAUD LAND' E N D E R B Y \ ] > * \ /' _ "iV**VlX" JN- S VDruzhnaya/General /SfA/ S f Auk/COATS ' " y C O A TBelirano SLd L d l arg L A N D p r \ ' — V&^y D««hjiaya/cenera.1 Beld ANTARCTIC •^W^fCN, uSS- fi?^^ /K\ Mawson \ MAC ROBERTSON LAN0\ \ *usi \ /PENINSULA' ^V^/^CRp^e J ^Vf (set mjp Mow) C^j V^^W^gSobralARG - Davis aust L Siple USA Amundsen-Scon OUEEN MARY LAND flMimy ELLSWORTH , U S A / ^ U S S R ') LAND °Vos1okussR/ r». / f c i i \ \ MARIE BYRO fee Shelf V\ . IAND WILKES LAND Scon ROSS|N2i? SEA jp>r/VICTORIAIj^V .TERRE ,; ' v / I ALAND n n \ \^S/ »ADEUL. n f i i f / / GEORGE V Ld .m^t Dumom d'Urville iranu Leningradskayra V' USSR,.'' \ -------"'•BAlLENYIs^ ANTARCTIC PENINSULA 1 Teniente Matienzo arc 2 Esperanza arg 3 Almirante Brown arg 4 Petrel arg 5 Decepcion arg 6 Vicecomodoro Marambio arg ' ANTARCTICA 7 Ariuro Prat chile 500 1000 Miles 8 Bernardo O'Higgms chile 9 Presidente Frei chile - • 1000 Kilomnre 10 Stonington I. -

Number 90 RECORDS of ,THE UNITED STATES ANTARCTIC

~ I Number 90 RECORDS OF ,THE UNITED STATES ANTARCTIC SERVICE Compiled by Charles E. Dewing and Laura E. Kelsay j ' ·r-_·_. J·.. ; 'i The National Archives Nat i on a 1 A r c hive s and R e c o rd s S e r vi c e General Services~Administration Washington: 1955 ---'---- ------------------------ ------~--- ,\ PRELIMINARY INVENTORY OF THE RECORDS OF THE UNITED STATES ANTARCTIC SERVICE {Record Group 1 Z6) Compiled by Charles E. Dewing and Laura E. Kelsay The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1955 National Archives Publication No. 56-8 i\ FORENORD To analyze and describe the permanently valuable records of the Fed eral Government preserved in the National Archives Building is one of the main tasks of the National Archives. Various kinds of finding aids are needed to facilitate the use of these records, and the first step in the records-description program is the compilation of preliminary inventories of the material in the 270-odd record groups to which the holdings of the National Archives are allocated. These inventories are called "preliminary" because they are provisional in character. They are prepared.as soon as possible after the records are received without waiting to screen out all disposable material or to per fect the arrangement of the records. They are compiled primarily for in ternal use: both as finding aids to help the staff render efficient refer ence service and as a means of establishing administrative control over the records. Each preliminary inventory contains an introduction that briefly states the history and fUnctions of the agency that accumulated the records. -

S. Antarctic Projects Officer Bullet

S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER BULLET VOLUME III NUMBER 8 APRIL 1962 Instructions given by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty ti James Clark Ross, Esquire, Captain of HMS EREBUS, 14 September 1839, in J. C. Ross, A Voya ge of Dis- covery_and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions, . I, pp. xxiv-xxv: In the following summer, your provisions having been completed and your crews refreshed, you will proceed direct to the southward, in order to determine the position of the magnet- ic pole, and oven to attain to it if pssble, which it is hoped will be one of the remarka- ble and creditable results of this expedition. In the execution, however, of this arduous part of the service entrusted to your enter- prise and to your resources, you are to use your best endoavours to withdraw from the high latitudes in time to prevent the ships being besot with the ice Volume III, No. 8 April 1962 CONTENTS South Magnetic Pole 1 University of Miohigan Glaoiologioal Work on the Ross Ice Shelf, 1961-62 9 by Charles W. M. Swithinbank 2 Little America - Byrd Traverse, by Major Wilbur E. Martin, USA 6 Air Development Squadron SIX, Navy Unit Commendation 16 Geological Reoonnaissanoe of the Ellsworth Mountains, by Paul G. Schmidt 17 Hydrographio Offices Shipboard Marine Geophysical Program, by Alan Ballard and James Q. Tierney 21 Sentinel flange Mapped 23 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 24 The Bulletin is pleased to present four firsthand accounts of activities in the Antarctic during the recent season. The Illustration accompanying Major Martins log is an official U.S. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

The Weddell Sea: an Historical Retrospect Dr

This article was downloaded by: [University of New England] On: 22 January 2015, At: 04:23 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Scottish Geographical Magazine Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsgj19 The Weddell Sea: An historical retrospect Dr. Wm.S. Bruce Published online: 30 Jan 2008. To cite this article: Dr. Wm.S. Bruce (1917) The Weddell Sea: An historical retrospect, Scottish Geographical Magazine, 33:6, 241-258, DOI: 10.1080/14702541708554307 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14702541708554307 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.