The Rivals; a Comedy by Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Passion for Opera the DUCHESS and the GEORGIAN STAGE

A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE PAUL BOUCHER JEANICE BROOKS KATRINA FAULDS CATHERINE GARRY WIEBKE THORMÄHLEN Published to accompany the exhibition A Passion for Opera: The Duchess and the Georgian Stage Boughton House, 6 July – 30 September 2019 http://www.boughtonhouse.co.uk https://sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/projects/passion-for-opera First published 2019 by The Buccleuch Living Heritage Trust The right of Paul Boucher, Jeanice Brooks, Katrina Faulds, Catherine Garry, and Wiebke Thormählen to be identified as the authors of the editorial material and as the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors. ISBN: 978-1-5272-4170-1 Designed by pmgd Printed by Martinshouse Design & Marketing Ltd Cover: Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Lady Elizabeth Montagu, Duchess of Buccleuch, 1767. Portrait commemorating the marriage of Elizabeth Montagu, daughter of George, Duke of Montagu, to Henry, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch. (Cat.10). © Buccleuch Collection. Backdrop: Augustus Pugin (1769-1832) and Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827), ‘Opera House (1800)’, in Rudolph Ackermann, Microcosm of London (London: Ackermann, [1808-1810]). © The British Library Board, C.194.b.305-307. Inside cover: William Capon (1757-1827), The first Opera House (King’s Theatre) in the Haymarket, 1789. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816) Richard Brinsley Sheridan was born in Dublin on 30th October 1751. Sheridan's parents moved to London, and in 1762, he was sent to Harrow School. After six years at Harrow, he went to live with his father in Bath who had found employment there as an elocution teacher. In March 1772, Sheridan eloped to France with a young woman called Elizabeth Linley. A marriage ceremony was carried out at Calais but soon afterwards the couple were caught by the girl's father. As a result of this behaviour, Sheridan was challenged to a duel. The fight took place on 2nd July 1772, during which Sheridan was seriously wounded. However, Sheridan recovered and after qualifying as a lawyer, Mr. Linley gave permission for the couple to marry. Sheridan began writing plays, and on 17th January 1775, the Covent Garden Theatre produced his comedy The Rivals. After a poor reception it was withdrawn. A revised version appeared soon after and it eventually become one of Britain's most popular comedies. Two other plays by Sheridan, St. Patrick's Day and The Duenna, were also successfully produced at the Covent Garden Theatre. In 1776, Sheridan joined with his father-in-law to purchase the Drury Lane Theatre for £35,000. The following year, he produced his most popular comedy, The School for Scandal. In 1776, Sheridan met Charles Fox, the leader of the Radical Whigs in the House of Commons. Sheridan now decided to abandon his writing in favour of a political career. On 12th September 1780, Sheridan became MP for Stafford. -

The English-Speaking Aristophanes and the Languages of Class Snobbery 1650-1914

Pre-print of Hall, E. in Aristophanes in Performance (Legenda 2005) The English-Speaking Aristophanes and the Languages of Class Snobbery 1650-1914 Edith Hall Introduction In previous chapters it has been seen that as early as the 1650s an Irishman could use Aristophanes to criticise English imperialism, while by the early 19th century the possibility was being explored in France of staging a topical adaptation of Aristophanes. In 1817, moreover, Eugene Scribe could base his vaudeville show Les Comices d’Athènes on Ecclesiazusae. Aristophanes became an important figure for German Romantics, including Hegel, after Friedrich von Schlegel had in 1794 published his fine essay on the aesthetic value of Greek comedy. There von Schlegel proposed that the Romantic ideals of Freedom and Joy (Freiheit, Freude) are integral to all art; since von Schlegel regarded comedy as containing them to the highest degree, for him it was the most democratic of all art forms. Aristophanic comedy made a fundamental contribution to his theory of a popular genre with emancipatory potential. One result of the philosophical interest in Aristophanes was that in the early decades of the 18th century, until the 1848 revolution, the German theatre itself felt the impact of the ancient comic writer: topical Lustspiele displayed interest in his plays, which provided a model for German poets longing for a political comedy, for example the remarkable satirical trilogy Napoleon by Friedrich Rückert (1815-18). This international context illuminates the experiences undergone by Aristophanic comedy in England, and what became known as Britain consequent upon the 1707 Act of Union. -

THE SCHOOL for SCANDAL by Richard Brinsley Sheridan

THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL by Richard Brinsley Sheridan THE AUTHOR Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816) was born in Dublin to a mother who was a playwright and a father who was an actor. He thus came by his talents honestly, though he far exceeded the modest accomplishments of his parents. Already one of the most brilliant and witty dramatists of the English stage before the age of thirty, he gave up his writing and went on to become the owner and producer of the Drury Lane theater, a well-regarded Whig member of the English Parliament, and a popular man-about-town. Despite his family’s poverty, he attended Harrow, a famous prep school, though he appears to have been unhappy there, largely because the rich boys at the school looked down on him because of his humble origins. The bitter taste of his school years drove his later ambitions, both for literary and political success and for acceptance in the highest strata of society. He used his profits from his writing to buy the theater and his profits from the theater to finance his political career and socially- active lifestyle. Sheridan was a tireless lover and a man who, no matter how much he earned, always managed to spend more. In 1772, he married a lovely young singer named Elizabeth Ann Linley; she had already, before her twentieth birthday, attracted the attention of several wealthy suitors twice her age, but she and Sheridan eloped to France without the knowledge or permission of either set of parents. Though she loved him deeply, he was not a one-woman sort of man, and his constant infidelities led to a temporary separation in 1790. -

Executive. *1 General Post Office

EXECUTIVE. *1 GENERAL POS? OFFICE. P. Mast. Qen. Clks. kc. GENERAL POST OFFICE. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation ofeach> from the 1st day ofOcidber, 1829. NAMES AND OFFICES: POSTMASTER GENERAL. William T.Barry,.. ASSISTANT POSTMASTERS' GENERAL. Charles, K. Gardner,. S.elah R. Hobbie, .. CHIEF CLERK. Obadiab. B..Brown,........... CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer,.:......, Joseph W. Haiid,. ; John Suter,.'.;; "... John McLeod, '....'. William G. Elliot, Michael T. Simpson,... Nicholas Tastet, David Saunders,... Rchard; Dement, Willing Blair, Thomas Arbuckle, Josiah f. Caldwell, "Joseph Haskell...... Samuel' Fitzhugh, William C.Ellison,.."... William Deming, Hyilliaift Cl'Lipscomb,. 'Thomas B; Addison,.:.'.' Matthias Ross, Davidj^oones, JfctitUy, Sinlpson,.....'.. A EXECUTIVE. GENERAL POST OFFICE. P Mast. Gen. Clks.kc. Compen NAMES AND OFFICES. sation &c. D. C. Grafton D. Hanson, 1000 00 Walter D. Addison,.. 1000 00 Andrew McD. Jackson,.... 1000 00 Arthur Nelson, 1000 00 John W. Overton, 1000 00 Henry S. Handy, Samuel Gwin, 1000 0® LemueLW. Ruggles, 1000 00 George S. Douglass, 1000 CO Preston S. Loughborough,. 1000 00 Francis G. Blackford, 1000 00 John G. Whitwell, 800 00 Thomas E. Waggoman,.... 800 0» John A Collins, Joseph Sherrill, 800 00 John F. Boone, 800 00 John G. Johnson, 800 0t John L. Storer, 800 0« William French, 800 09 James H. Doughty, 800 00 James Coolidge,., 800 00 Charles S. Williams, EdmundF. Brown, 800 00 Alexander H. Fitzhugh,.... 800 00 800 00 FOR OPENING DEAD LETTERS. 800 00 500 00 Charles Bell, 400 00 William Harvey,. 400 00 MESSENGER. Joseph Borrows, 700 0» ASSISTANT MESSENGERS.' Nathaniel Herbert,., 350 00 William Jackson,,. -

Punch and Judy’ and Cultural Appropriation Scott Cutler Shershow

Bratich z Amassing the Multitude 1 Popular Culture in History 2 Interpretational Audiences Bratich z Amassing the Multitude 3 1 ‘Punch and Judy’ and Cultural Appropriation Scott Cutler Shershow It is a drama in two acts, is Punch. Ah, it’s a beautiful history; there’s a deal of morals with it, and there’s a large volume wrote about it. (Mayhew, 1967 [1861–62] 3: 46) n The New Yorker magazine of 2 August 1993, a cartoon depicts two grotesque, hook-nosed figures, male and female, fighting with cudgels Iwhile sitting at a table at an elegant restaurant, while a waiter stands by asking, ‘Are you folks ready to order?’ The cartoon prompts me to ask: why should Punch and Judy still be recognizable icons of domestic violence and social trangression at the end of the twentieth century, even to readers who may have never seen an actual ‘Punch and Judy’ puppet show? Versions of this question have, of course, been asked before. In answering them, however, scholars typically claim a primeval or archetypal status for Punch, pointing to his alleged cultural descent from a whole constellation of ancient sources including, for example, ‘the religious plays of medieval England’, ‘the impro- vised farces of the Italian comedians’, and ‘the folk festivals of pagan Greece’ (Speaight, 1970: 230). I will take the opposite position, attempting to locate ‘Punch and Judy’ in the actual processes of social life and cultural transmis- sion in a particular period, and in the dynamic interaction of cultural practices and their discursive reinterpretation. Such an approach may do more justice to the cultural meaning of figures who still apparently embody, as they do in the cartoon, anxieties about status, class, gender, and relative social power. -

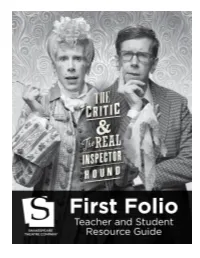

Real Inspector Hound Synopsis 4 Perceptions

FIRST FOLIO: TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE GUIDE Consistent with the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s central mission to be the leading force in producing and preserving the Table of Contents highest quality classic theatre, the Education Department challenges learners of all ages to explore the ideas, emotions The Critic Synopsis 3 and principles contained in classic texts and to discover the connection between classic theatre and our modern The Real Inspector Hound Synopsis 4 perceptions. We hope that this First Folio: Teacher and Student Resource Guide will prove useful to you while preparing to Who’s Who 5 attend The Critic & The Real Inspector Hound. About the Authors 7 First Folio provides information and activities to help students I, Critic 9 form a personal connection to the play before attending the By Jeffrey Hatcher production. First Folio contains material about the playwrights, their world and their works. Also included are approaches to Tom Stoppard: An Introduction 10 explore the plays and productions in the classroom before and after the performance. Classroom Activities 11 First Folio is designed as a resource both for teachers and Questions for Discussion 16 students. All Folio activities meet the “Vocabulary Acquisition and Use” and “Knowledge of Language” requirements for the Theatre Etiquette 17 grades 8-12 Common Core English Language Arts Standards. We encourage you to photocopy these articles and activities and use them as supplemental material to the text. Enjoy the show! Founding Sponsors The First Folio Teacher and Student Resource Guide for Miles Gilburne and Nina Zolt the 2015-2016 Season was developed by the Shakespeare Theatre Company Education Department: Leadership Support The Beech Street Foundation Director of Education Samantha K. -

The Rise and Fall of the New Edinburgh Theatre Royal, 1767-1859

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 1-1-2015 The Rise and Fall of the New Edinburgh Theatre Royal, 1767-1859: Archival Documents and Performance History Judith Bailey Slagle East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Citation Information Slagle, Judith Bailey. 2015. The Rise and Fall of the New Edinburgh Theatre Royal, 1767-1859: Archival Documents and Performance History. Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Theatre Research. Vol.30(1,2). 5-29. https://rectrjournal.org/current-issue/ ISSN: 0034-5822 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise and Fall of the New Edinburgh Theatre Royal, 1767-1859: Archival Documents and Performance History Copyright Statement This document was published with permission from the journal. It was originally published in the Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Theatre Research. This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/718 Restoration and Eighteenth- Century Theatre Research “The Rise and Fall of the New Edinburgh Theatre Royal, 1767-1859: Archival Documents and Performance History” BY JUDITH BAILEY SLAGLE Volume 30, Issues 1 and 2 (Summer and Winter 2015) Recommended Citation: Slagle, Judith Bailey. -

Download Full Book

Staging Governance O'Quinn, Daniel Published by Johns Hopkins University Press O'Quinn, Daniel. Staging Governance: Theatrical Imperialism in London, 1770–1800. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.60320. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/60320 [ Access provided at 30 Sep 2021 18:04 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Staging Governance This page intentionally left blank Staging Governance theatrical imperialism in london, 1770–1800 Daniel O’Quinn the johns hopkins university press Baltimore This book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Karl and Edith Pribram Endowment. © 2005 the johns hopkins university press All rights reserved. Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 987654321 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data O’Quinn, Daniel, 1962– Staging governance : theatrical imperialism in London, 1770–1800 / Daniel O’Quinn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8018-7961-2 (hardcover : acid-free paper) 1. English drama—18th century—History and criticism. 2. Imperialism in literature. 3. Politics and literature—Great Britain—History—18th century. 4. Theater—England— London—History—18th century. 5. Political plays, English—History and criticism. 6. Theater—Political aspects—England—London. 7. Colonies in literature. I. Title. PR719.I45O59 2005 822′.609358—dc22 2004026032 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

The Theatre of Shelley

Jacqueline Mulhallen The Theatre of Shelley OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/27 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Jacqueline Mulhallen has studied and worked as an actor and writer in both England and Australia and won a scholarship to study drama in Finland. She worked as performer and writer with Lynx Theatre and Poetry and her plays Sylvia and Rebels and Friends toured England and Ireland (1987-1997). Publications include ‘Focus on Finland’, Theatre Australia, 1979; (with David Wright) ‘Samuel Johnson: Amateur Physician’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1982; ‘Sylvia Pankhurst’s Northern Tour’, www.sylviapankhurst. com, 2008; ‘Sylvia Pankhurst’s Paintings: A Missing Link’, Women’s History Magazine, 2009 and she is a contributor to the Oxford Handbook of the Georgian Playhouse 1737-1832 (forthcoming). Jacqueline Mulhallen The Theatre of Shelley Cambridge 2010 Open Book Publishers CIC Ltd., 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2010 Jacqueline Mulhallen. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Details of allowances and restrictions are available at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website: http://www.openbookpublishers.com ISBN Hardback: 978-1-906924-31-7 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-906924-30-0 ISBN Digital (pdf): 978-1-906924-32-4 Acknowledgment is made to the The Jessica E. -

Illegitimate Theatre in London, –

ILLEGITIMATE THEATRE IN LONDON, – JANE MOODY The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk West th Street, New York, –, USA www.cup.org Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia Ruiz de Alarcón , Madrid, Spain © Jane Moody This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Monotype Baskerville /. pt System QuarkXPress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Moody, Jane. Illegitimate theatre in London, ‒/Jane Moody. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. . Theater – England – London – History – th century. Theater – England – London – History – th century. Title. .6 Ј.Ј–dc hardback Contents List of illustrations page ix Acknowledgements xi List of abbreviations xiii Prologue The invention of illegitimate culture The disintegration of legitimate theatre Illegitimate production Illegitimate Shakespeares Reading the theatrical city Westminster laughter Illegitimate celebrities Epilogue Select bibliography Index vii Illustrations An Amphitheatrical Attack of the Bastile, engraved by S. Collings and published by Bentley in . From the Brady collection, by courtesy of the Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford. page The Olympic Theatre, Wych Street, by R.B. Schnebbelie, . By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Royal Coburg Theatre by R.B. Schnebbelie, . By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Royal Circus Theatre by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin, published by Ackermann in .