01 Conefrey:Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Biographies for Talented Readers, a Bibliography

Biographies for Talented Readers, A Bibliography Ann Robinson, Director Center for Gifted Education University of Arkansas at Little Rock http://giftedctr.ualr.edu Person Title Author Publisher AR Level Louisa May Alcott Louisa May & Mr. Julie Dunlap & Dial Books 3.9 Thoreau’s Flute Marybeth Lorbiecki Marian Anderson The Voice That Challenged Russell Freedman Clarion Books 8.2 a Nation: Marian Anderson and the Struggle for Equal Rights Marian Anderson When Marian Sang Pam Ryan & Brian Scholastic Press 5.2 Selznick Mary Anning Stone Girl, Bone Girl Laurence Anholt & Orchard Books 4.5 Sheila Moxley Mary Anning Rare Treasure: Mary Don Brown Houghton Mifflin 5.4 Anning and Her Remarkable Discoveries Mary Anning Mary Anning and the Sea Jeannine Atkins Farrar Straus Giroux 4.6 Dragon John James The Boy Who Drew Birds Jacqueline Davies Houghton Mifflin 4.4 Audubon John James Into the Woods: John James Robert Burleigh Simon & Schuster 4.7 Audubon Audubon Lives His Dream Ann Bancroft & Ann and Liv Cross Zoe Alderfer Ryan Da Capo Press (ages 7 Liv Arnesen Antarctica: A Dream Come & Nicholas Reti to 12) True! Benjamin Banneker Benjamin Banneker Kevin Conley Chelsea House (grades 6 to 12) John Bardsley Sparrow Jack Mordicai Gerstein Farrar Straus Giroux 3.7 Ibn Battuta Traveling Man: The James Rumford Houghton Mifflin 4.0 Journey of Ibn Battuta 1325-1354 Wilson A. Bentley My Brother Loved Mary Bahr & Laura Boyd Mills Press 3.4 Snowflakes Jacobsen Wilson A. Bentley Snowflake Bentley Jacqueline Briggs Houghton Mifflin 4.1 Martin & Mary Azarian Stephen -

Babe Didrikson Zaharias Super-Athlete

2 MORE THAN 150 YEARS OF WOMEN’S HISTORY March is Women’s History Month. The Women’s Rights Movement started in Seneca Falls, New York, with the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848.Out of the convention came a declaration modeled upon the Declaration of Independence, written by a woman named Elizabeth Cady THE WOMEN WE HONOR Stanton. They worked inside and outside of their homes. business and labor; science and medicine; sports and It demanded that women be given They pressed for social changes in civil rights, the peace exploration; and arts and entertainment. all the rights and privileges that belong movement and other important causes. As volunteers, As you read our mini-biographies of these women, they did important charity work in their communities you’ll be asked to think about what drove them toward to them as citizens of the United States. and worked in places like libraries and museums. their achievements. And to think how women are Of course, it was many years before Women of every race, class and ethnic background driven to achieve today. And to consider how women earned all the rights the have made important contributions to our nation women will achieve in the future. Seneca Falls convention demanded. throughout its history. But sometimes their contribution Because women’s history is a living story, our list of has been overlooked or underappreciated or forgotten. American women includes women who lived “then” American women were not given Since 1987, our nation has been remembering and women who are living—and achieving—”now.” the right to vote until 1920. -

Chief Executive Officer Search

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER SEARCH 1 Canal Street • PO Box 335 • Seneca Falls, NY 13148 • womenofthehall.org • (315) 568-8060 T HE S EA RC H The Board of Directors of the National Women’s Hall of Fame invites applications and nominations of highly experienced, energetic, and creative candidates for the position of Chief Executive Officer (CEO). Candidates should be attracted to the opportunity to provide highly transformative leadership for the nation’s premier institution honoring exceptional American women who embody the National Women’s Hall of Fame mission of “Showcasing great women . Inspiring all”. The National Women’s Hall of Fame (NWHF/the Hall) is expanding in every way – in size, in reach, in influence. To better accommodate these ambitions, the NWHF rehabilitated the historic 1844 Seneca Knitting Mill located on the Seneca-Cayuga branch of the Erie Canal in Seneca Falls, NY, and moved into it in 2020. This extraordinary achievement was completed over nine years with 10 million dollars of funding. The NWHF is eager to embrace the opportunities enabled by this new, expansive space, including honoring the importance and sense of “place” that Seneca Falls and the Erie Canal system have played in the history of the economic, social, and human rights movements of the United States of America. Following this historic move, in this historic year celebrating the centennial of women’s suffrage, the National Women’s Hall of Fame now seeks a talented, proven leader dedicated to expanding the Hall’s national footprint, advancing its fundraising capacity, strengthening its organizational structure, and planning and implementing an ambitious agenda of new programs and exhibits. -

Recordings by Women Table of Contents

'• ••':.•.• %*__*& -• '*r-f ":# fc** Si* o. •_ V -;r>"".y:'>^. f/i Anniversary Editi Recordings By Women table of contents Ordering Information 2 Reggae * Calypso 44 Order Blank 3 Rock 45 About Ladyslipper 4 Punk * NewWave 47 Musical Month Club 5 Soul * R&B * Rap * Dance 49 Donor Discount Club 5 Gospel 50 Gift Order Blank 6 Country 50 Gift Certificates 6 Folk * Traditional 52 Free Gifts 7 Blues 58 Be A Slipper Supporter 7 Jazz ; 60 Ladyslipper Especially Recommends 8 Classical 62 Women's Spirituality * New Age 9 Spoken 64 Recovery 22 Children's 65 Women's Music * Feminist Music 23 "Mehn's Music". 70 Comedy 35 Videos 71 Holiday 35 Kids'Videos 75 International: African 37 Songbooks, Books, Posters 76 Arabic * Middle Eastern 38 Calendars, Cards, T-shirts, Grab-bag 77 Asian 39 Jewelry 78 European 40 Ladyslipper Mailing List 79 Latin American 40 Ladyslipper's Top 40 79 Native American 42 Resources 80 Jewish 43 Readers' Comments 86 Artist Index 86 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124-R, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 M-F 9-6 INQUIRIES: 919-683-1570 M-F 9-6 ordering information FAX: 919-682-5601 Anytime! PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are tem CATALOG EXPIRATION AND PRICES: We will honor don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and porarily out of stock on a title, we will automatically prices in this catalog (except in cases of dramatic schools). Make check or money order payable to back-order it unless you include alternatives (should increase) until September. -

First Ladies

INSPIRATION: In this photo from June 2, 1920, Mrs. James Rector, Mary Dubrow, and Alice Paul, officers of the National Woman’s Party, stand in front of the Washington headquarters before leaving for the Chicago Convention to take charge of the suffrage attack on the convention of the Republican Party. PHOTO: Library of Congress FIRST LADIES The names in this quilt are • women who were the first of their sex or ethnicity to do things that were previously done only by men or people of other ethnicity or sexual orientation • notable women who moved equality forward for others in their generation IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER BY FIRST NAME: 1. Aida Alvarez: first Hispanic women to hold a cabinet-level position 2. Alice K. Kurashige: first Japanese-American woman commissioned in the United States Marine Corps 1964 3. Alice Paul: proposed the Equal Rights Amendment for the first time, 1923 4. Althea Gibson: first African-American tennis player to win a singles title at Wimbledon 1967 5. Amelia Earhart: first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic 6. Anita Hill: campaigner against sexual harassment 7. Ann Bancroft: first woman to reach the North Pole by foot and dogsled 1986 8. Ann Baumgartner: first woman to fly a jet aircraft 1944 9. Anna Leah Fox: first woman to receive the Purple Heart 1942 10. Anna Mae Hays and Annise Parker: first openly gay individuals to serve as mayor of one of the top ten US cities 2008 11. Antonia Novello: first woman (and first Hispanic) U.S. Surgeon General 1990 12. Aretha Franklin: first woman inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 13. -

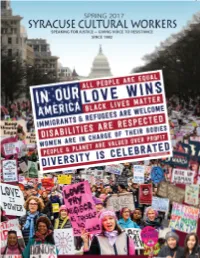

800.949.5139 Syracuseculturalworkers.Com 3 4

CONTENTS THREE FORMATS! BY PRODUCT Accordion Posters . .2,5,8,24 Bookmarks . 9,22 Buttons/Stickers . 14-15,22 or 24 Cards • Notecards/Collections . 3,18,19,21 • Postcards . 7,16,17,23 CDs . 7,21,web Clothes Drying Racks . .20 Exhibits– Sisters of Freedom & more . .web Flags . .5 Framed Small Prints . .18,19 FREE Map Book . .13 2017-18 Holiday Products . .4 Magnets . 4,13 Welcome Mugs/Coffee . .21 SCW©2012, 2013 Order Form . .12 Placemats . .8 Each of the seven Posters, Free/SALE! . .13 beautiful letters T-Shirts . 3,10,11,21,22,24 contains a phrase NEW I, Too, Sing America • Onesies . .4 that represents Portrait Jaleel Campbell SCW ©2017 Water Bottles . .20 the feminist, Text on poster: Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Yard Signs / Placards . .23 progressive Hughes (1902-1967) has inspired generations values we with his powerful writing. His 1926 poem “I, Too” is embrace. displayed on the outside of the National Museum BY THEME A wonderful of African American History and Culture in welcoming gift. Washington, DC which opened in 2016. Most themes have additional products • Small: vertical, • P756CW 12x18...$12 on our website. Search by THEME! 5x35, string • FP756CW bronze frame ...$95 African American . .2,6,10,13,15 included. • C088CW... 6/$12.95 Bikes . 10,14 P695CW…$14 C088CWD single... $3 Boys/Men . 11,15 5+ @ $12 • F088CW bronze frame ...$30 Banned Books . 9,11 • Large: vertical, • T171CW...12/$11.95 Black Lives Matter . 6,10,13,23 9x60, string T171CWD single...$1.25 NEW Bullying . 13,web included. Children/Education . 2,4,8,9,14 P705CW…$25 Civil Rights Movement . -

Faye Glenn Abdellah 1919 - • As a Nurse Researcher Transformed Nursing Theory, Nursing Care, and Nursing Education

Faye Glenn Abdellah 1919 - • As a nurse researcher transformed nursing theory, nursing care, and nursing education • Moved nursing practice beyond the patient to include care of families and the elderly • First nurse and first woman to serve as Deputy Surgeon General Bella Abzug 1920 – 1998 • As an attorney and legislator championed women’s rights, human rights, equality, peace and social justice • Helped found the National Women’s Political Caucus Abigail Adams 1744 – 1818 • An early feminist who urged her husband, future president John Adams to “Remember the Ladies” and grant them their civil rights • Shaped and shared her husband’s political convictions Jane Addams 1860 – 1935 • Through her efforts in the settlement movement, prodded America to respond to many social ills • Received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 Madeleine Korbel Albright 1937 – • First female Secretary of State • Dedicated to policies and institutions to better the world • A sought-after global strategic consultant Tenley Albright 1934 – • First American woman to win a world figure skating championship; triumphed in figure skating after overcoming polio • First winner of figure skating’s triple crown • A surgeon and blood plasma researcher who works to eradicate polio around the world Louisa May Alcott 1832 – 1888 • Prolific author of books for American girls. Most famous book is Little Women • An advocate for abolition and suffrage – the first woman to register to vote in Concord, Massachusetts in 1879 Florence Ellinwood Allen 1884 – 1966 • A pioneer in the legal field with an amazing list of firsts: The first woman elected to a judgeship in the U.S. First woman to sit on a state supreme court. -

Bibliography of Biographies for Talent Development Compiled by Ann Robinson, Jodie Mahony Center for Gifted Education

Bibliography of Biographies for Talent Development Compiled by Ann Robinson, Jodie Mahony Center for Gifted Education Person Title Author Publisher AR Level Louisa May Alcott Louisa May & Mr. Thoreau’s Flute Julie Dunlap & Dial Books 3.9 Marybeth Lorbiecki Marian Anderson Marian Anderson: A Voice Uplifted Victoria Garnett Sterling 7 Jones Marian Anderson The Voice That Challenged a Nation: Marian Russell Freedman Clarion Books 8.2 Anderson and the Struggle for Equal Rights Marian Anderson When Marian Sang Pam Ryan & Brian Scholastic Press 5.2 Selznick Mary Anning Stone Girl, Bone Girl Laurence Anholt & Orchard Books 4.5 Sheila Moxley Mary Anning Rare Treasure: Mary Anning and Her Don Brown Houghton Mifflin 5.4 Remarkable Discoveries Mary Anning Mary Anning and the Sea Dragon Jeannine Atkins Farrar Straus Giroux 4.6 Fred and Adele Astaire Footwork: The Story of Fred and Adele Astaire Roxane Orgill Candlewick Press (ages 4 to 8) John James Audubon The Boy Who Drew Birds Jacqueline Davies Houghton Mifflin 4.4 John James Audubon Into the Woods: John James Audubon Lives Robert Burleigh Simon & Schuster 4.7 His Dream Alia Muhammad Baker The Librarian of Basra: A True Story from Iraq Jeanette Winter Harcourt, Inc. 3.2 Ann Bancroft & Ann and Liv Cross Antarctica: A Dream Come Zoe Alderfer Ryan Da Capo Press (ages 7 Liv Arnesen True! & Nicholas Reti to 12) Benjamin Banneker Benjamin Banneker Kevin Conley Chelsea House (grades 6 to 12) Benjamin Banneker Benjamin Banneker Catherine Welch Barnes & Noble 4.2 John Bardsley Sparrow Jack Mordicai Gerstein Farrar Straus Giroux 3.7 Ibn Battuta Traveling Man: The Journey of Ibn Battuta James Rumford Houghton Mifflin 4.0 1325-1354 Wilson A. -

Super Bowls on CBS Game History

Super Bowl I January 15, 1967, Memorial Coliseum, Los Angeles, Calif. Green Bay 35 - Kansas City 10 CBS (Ray Scott, Jack Whitaker, Frank Gifford, Pat Summerall), NBC (Curt Gowdy, Paul Christman, Charlie Jones) CBS Ad cost: $42,500; NBC Ad cost: $37,500 CBS viewers: 34.2 million; NBC viewers: 24.4 million. CBS Rating/Share: 23.0/44 Super Bowl Lead-Out Program: Lassie (7:30-8:00 PM) Rating/Share: 15.6/25 Viewers: 17.7 million Entertainment Pregame: University of Arizona & Grambling University with Al Hirt National Anthem: Universities of Arizona & Michigan Bands Coin Toss: Game Official Halftime: Universities of Arizona & Michigan Bands GREEN BAY 35 – KANSAS CITY 10 —The Green Bay Packers opened the Super Bowl series by defeating Kansas City’s American Football League champions 35-10 behind the passing of Bart Starr, the receiving of Max McGee, and a key interception by all-pro safety Willie Wood. Green Bay broke open the game with three second-half touchdowns, the first of which was set up by Wood’s 50-yard return of an interception to the Chiefs’ five-yard line. McGee, filling in for ailing Boyd Dowler after having caught only four passes all season, caught seven from Starr for 138 yards and two touchdowns. Elijah Pitts ran for two other scores. The Chiefs’ 10 points came in the second quarter, the only touchdown on a seven- yard pass from Len Dawson to Curtis McClinton. Starr completed 16-of-23 passes for 250 yards and two touchdowns and was chosen the Most Valuable Player. -

Scavenger Hunt- Women in History

Fill in the chart below as you explore the internet and learn more about each of these exceptional women in American history. After reading the short biographical information about each outstanding woman, answer the question related to her AND write down an additional interesting piece of information about her life. Woman Answer Another bit of interesting information Madam C. J. Walker How did she become the first female African American millionaire? Rosa Parks How many days did the Montgomery bus boycott last? Ida Wells Barnett What did she do in 1884 that was similar to what Rosa Parks did by refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white man in 1955? Wilma Rudolph What obstacles did she have to overcome in order to win 3 gold medals in the 1960 Olympics? Dorothea Dix She was inducted into the Women's Hall of Fame because of her role as a champion for the rights of what group of people? Sacajawea What famous team of explorers did she travel with? Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony What prominent organization was led by these two women? Woman Answer Another bit of interesting information Deborah Sampson What did she do during the Revolutionary War and why? Betsy Ross Who asked her to make the first American flag? Harriet Tubman What was the total amount of money offered as a reward if she could be captured? Rebecca Lobo In 1996 she won an Olympic gold medal in what sport? Anna Breadin What did this American woman invent in 1889? Sally Ride What "first" did this famous woman astronaut accomplish? Helen Keller How did she (although -

Women's Contributions to the United States: Honoring the Past And

The School Board of Broward County, Florida Benjamin J. Williams, Chair Beverly A. Gallagher, Vice Chair Carole L. Andrews Robin Bartleman Darla L. Carter Maureen S. Dinnen Stephanie Arma Kraft, Esq. Robert D. Parks, Ed.D. Marty Rubinstein Dr. Frank Till Superintendent of Schools The School Board of Broward County, Florida, prohibits any policy or procedure which results in discrimination on the basis of age, color, disability, gender, national origin, marital status, race, religion or sexual orientation. Individuals who wish to file a discrimination and/or harassment complaint may call the Director of Equal Educational Opportunities at (754) 321-2150 or Teletype Machine TTY (754) 321-2158. www.browardschools.com Women’s Contributions to the United States: Honoring the Past and Challenging the Future Manual Grades K-12 Dr. Earlean C. Smiley Deputy Superintendent Curriculum and Instruction/Student Support Sayra Vélez Hughes Executive Director Multicultural & ESOL Program Services Education Department Dr. Elizabeth L. Watts Multicultural Curriculum Development/Training Specialist Multicultural Department Barbara Billington Linda Medvin Marion M. Williams Resource Teachers WOMEN’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE UNITED STATES: HONORING THE PAST AND CHALLENGING THE FUTURE TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................... i Writing Team ............................................................................................................................