Compiler: Parsing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

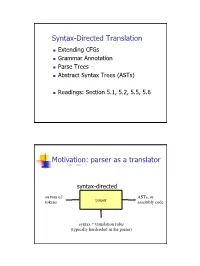

Syntax-Directed Translation, Parse Trees, Abstract Syntax Trees

Syntax-Directed Translation Extending CFGs Grammar Annotation Parse Trees Abstract Syntax Trees (ASTs) Readings: Section 5.1, 5.2, 5.5, 5.6 Motivation: parser as a translator syntax-directed translation stream of ASTs, or tokens parser assembly code syntax + translation rules (typically hardcoded in the parser) 1 Mechanism of syntax-directed translation syntax-directed translation is done by extending the CFG a translation rule is defined for each production given X Æ d A B c the translation of X is defined in terms of translation of nonterminals A, B values of attributes of terminals d, c constants To translate an input string: 1. Build the parse tree. 2. Working bottom-up • Use the translation rules to compute the translation of each nonterminal in the tree Result: the translation of the string is the translation of the parse tree's root nonterminal Why bottom up? a nonterminal's value may depend on the value of the symbols on the right-hand side, so translate a non-terminal node only after children translations are available 2 Example 1: arith expr to its value Syntax-directed translation: the CFG translation rules E Æ E + T E1.trans = E2.trans + T.trans E Æ T E.trans = T.trans T Æ T * F T1.trans = T2.trans * F.trans T Æ F T.trans = F.trans F Æ int F.trans = int.value F Æ ( E ) F.trans = E.trans Example 1 (cont) E (18) Input: 2 * (4 + 5) T (18) T (2) * F (9) F (2) ( E (9) ) int (2) E (4) * T (5) Annotated Parse Tree T (4) F (5) F (4) int (5) int (4) 3 Example 2: Compute type of expr E -> E + E if ((E2.trans == INT) and (E3.trans == INT) then E1.trans = INT else E1.trans = ERROR E -> E and E if ((E2.trans == BOOL) and (E3.trans == BOOL) then E1.trans = BOOL else E1.trans = ERROR E -> E == E if ((E2.trans == E3.trans) and (E2.trans != ERROR)) then E1.trans = BOOL else E1.trans = ERROR E -> true E.trans = BOOL E -> false E.trans = BOOL E -> int E.trans = INT E -> ( E ) E1.trans = E2.trans Example 2 (cont) Input: (2 + 2) == 4 1. -

Derivatives of Parsing Expression Grammars

Derivatives of Parsing Expression Grammars Aaron Moss Cheriton School of Computer Science University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada [email protected] This paper introduces a new derivative parsing algorithm for recognition of parsing expression gram- mars. Derivative parsing is shown to have a polynomial worst-case time bound, an improvement on the exponential bound of the recursive descent algorithm. This work also introduces asymptotic analysis based on inputs with a constant bound on both grammar nesting depth and number of back- tracking choices; derivative and recursive descent parsing are shown to run in linear time and constant space on this useful class of inputs, with both the theoretical bounds and the reasonability of the in- put class validated empirically. This common-case constant memory usage of derivative parsing is an improvement on the linear space required by the packrat algorithm. 1 Introduction Parsing expression grammars (PEGs) are a parsing formalism introduced by Ford [6]. Any LR(k) lan- guage can be represented as a PEG [7], but there are some non-context-free languages that may also be represented as PEGs (e.g. anbncn [7]). Unlike context-free grammars (CFGs), PEGs are unambiguous, admitting no more than one parse tree for any grammar and input. PEGs are a formalization of recursive descent parsers allowing limited backtracking and infinite lookahead; a string in the language of a PEG can be recognized in exponential time and linear space using a recursive descent algorithm, or linear time and space using the memoized packrat algorithm [6]. PEGs are formally defined and these algo- rithms outlined in Section 3. -

Backtrack Parsing Context-Free Grammar Context-Free Grammar

Context-free Grammar Problems with Regular Context-free Grammar Language and Is English a regular language? Bad question! We do not even know what English is! Two eggs and bacon make(s) a big breakfast Backtrack Parsing Can you slide me the salt? He didn't ought to do that But—No! Martin Kay I put the wine you brought in the fridge I put the wine you brought for Sandy in the fridge Should we bring the wine you put in the fridge out Stanford University now? and University of the Saarland You said you thought nobody had the right to claim that they were above the law Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 1 Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 2 Problems with Regular Problems with Regular Language Language You said you thought nobody had the right to claim [You said you thought [nobody had the right [to claim that they were above the law that [they were above the law]]]] Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 3 Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 4 Problems with Regular Context-free Grammar Language Nonterminal symbols ~ grammatical categories Is English mophology a regular language? Bad question! We do not even know what English Terminal Symbols ~ words morphology is! They sell collectables of all sorts Productions ~ (unordered) (rewriting) rules This concerns unredecontaminatability Distinguished Symbol This really is an untiable knot. But—Probably! (Not sure about Swahili, though) Not all that important • Terminals and nonterminals are disjoint • Distinguished symbol Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 5 Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 6 Context-free Grammar Context-free -

Adaptive LL(*) Parsing: the Power of Dynamic Analysis

Adaptive LL(*) Parsing: The Power of Dynamic Analysis Terence Parr Sam Harwell Kathleen Fisher University of San Francisco University of Texas at Austin Tufts University [email protected] [email protected] kfi[email protected] Abstract PEGs are unambiguous by definition but have a quirk where Despite the advances made by modern parsing strategies such rule A ! a j ab (meaning “A matches either a or ab”) can never as PEG, LL(*), GLR, and GLL, parsing is not a solved prob- match ab since PEGs choose the first alternative that matches lem. Existing approaches suffer from a number of weaknesses, a prefix of the remaining input. Nested backtracking makes de- including difficulties supporting side-effecting embedded ac- bugging PEGs difficult. tions, slow and/or unpredictable performance, and counter- Second, side-effecting programmer-supplied actions (muta- intuitive matching strategies. This paper introduces the ALL(*) tors) like print statements should be avoided in any strategy that parsing strategy that combines the simplicity, efficiency, and continuously speculates (PEG) or supports multiple interpreta- predictability of conventional top-down LL(k) parsers with the tions of the input (GLL and GLR) because such actions may power of a GLR-like mechanism to make parsing decisions. never really take place [17]. (Though DParser [24] supports The critical innovation is to move grammar analysis to parse- “final” actions when the programmer is certain a reduction is time, which lets ALL(*) handle any non-left-recursive context- part of an unambiguous final parse.) Without side effects, ac- free grammar. ALL(*) is O(n4) in theory but consistently per- tions must buffer data for all interpretations in immutable data forms linearly on grammars used in practice, outperforming structures or provide undo actions. -

Parsing 1. Grammars and Parsing 2. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Parsing 3

Syntax Parsing syntax: from the Greek syntaxis, meaning “setting out together or arrangement.” 1. Grammars and parsing Refers to the way words are arranged together. 2. Top-down and bottom-up parsing Why worry about syntax? 3. Chart parsers • The boy ate the frog. 4. Bottom-up chart parsing • The frog was eaten by the boy. 5. The Earley Algorithm • The frog that the boy ate died. • The boy whom the frog was eaten by died. Slide CS474–1 Slide CS474–2 Grammars and Parsing Need a grammar: a formal specification of the structures allowable in Syntactic Analysis the language. Key ideas: Need a parser: algorithm for assigning syntactic structure to an input • constituency: groups of words may behave as a single unit or phrase sentence. • grammatical relations: refer to the subject, object, indirect Sentence Parse Tree object, etc. Beavis ate the cat. S • subcategorization and dependencies: refer to certain kinds of relations between words and phrases, e.g. want can be followed by an NP VP infinitive, but find and work cannot. NAME V NP All can be modeled by various kinds of grammars that are based on ART N context-free grammars. Beavis ate the cat Slide CS474–3 Slide CS474–4 CFG example CFG’s are also called phrase-structure grammars. CFG’s Equivalent to Backus-Naur Form (BNF). A context free grammar consists of: 1. S → NP VP 5. NAME → Beavis 1. a set of non-terminal symbols N 2. VP → V NP 6. V → ate 2. a set of terminal symbols Σ (disjoint from N) 3. -

Abstract Syntax Trees & Top-Down Parsing

Abstract Syntax Trees & Top-Down Parsing Review of Parsing • Given a language L(G), a parser consumes a sequence of tokens s and produces a parse tree • Issues: – How do we recognize that s ∈ L(G) ? – A parse tree of s describes how s ∈ L(G) – Ambiguity: more than one parse tree (possible interpretation) for some string s – Error: no parse tree for some string s – How do we construct the parse tree? Compiler Design 1 (2011) 2 Abstract Syntax Trees • So far, a parser traces the derivation of a sequence of tokens • The rest of the compiler needs a structural representation of the program • Abstract syntax trees – Like parse trees but ignore some details – Abbreviated as AST Compiler Design 1 (2011) 3 Abstract Syntax Trees (Cont.) • Consider the grammar E → int | ( E ) | E + E • And the string 5 + (2 + 3) • After lexical analysis (a list of tokens) int5 ‘+’ ‘(‘ int2 ‘+’ int3 ‘)’ • During parsing we build a parse tree … Compiler Design 1 (2011) 4 Example of Parse Tree E • Traces the operation of the parser E + E • Captures the nesting structure • But too much info int5 ( E ) – Parentheses – Single-successor nodes + E E int 2 int3 Compiler Design 1 (2011) 5 Example of Abstract Syntax Tree PLUS PLUS 5 2 3 • Also captures the nesting structure • But abstracts from the concrete syntax a more compact and easier to use • An important data structure in a compiler Compiler Design 1 (2011) 6 Semantic Actions • This is what we’ll use to construct ASTs • Each grammar symbol may have attributes – An attribute is a property of a programming language construct -

Sequence Alignment/Map Format Specification

Sequence Alignment/Map Format Specification The SAM/BAM Format Specification Working Group 3 Jun 2021 The master version of this document can be found at https://github.com/samtools/hts-specs. This printing is version 53752fa from that repository, last modified on the date shown above. 1 The SAM Format Specification SAM stands for Sequence Alignment/Map format. It is a TAB-delimited text format consisting of a header section, which is optional, and an alignment section. If present, the header must be prior to the alignments. Header lines start with `@', while alignment lines do not. Each alignment line has 11 mandatory fields for essential alignment information such as mapping position, and variable number of optional fields for flexible or aligner specific information. This specification is for version 1.6 of the SAM and BAM formats. Each SAM and BAMfilemay optionally specify the version being used via the @HD VN tag. For full version history see Appendix B. Unless explicitly specified elsewhere, all fields are encoded using 7-bit US-ASCII 1 in using the POSIX / C locale. Regular expressions listed use the POSIX / IEEE Std 1003.1 extended syntax. 1.1 An example Suppose we have the following alignment with bases in lowercase clipped from the alignment. Read r001/1 and r001/2 constitute a read pair; r003 is a chimeric read; r004 represents a split alignment. Coor 12345678901234 5678901234567890123456789012345 ref AGCATGTTAGATAA**GATAGCTGTGCTAGTAGGCAGTCAGCGCCAT +r001/1 TTAGATAAAGGATA*CTG +r002 aaaAGATAA*GGATA +r003 gcctaAGCTAA +r004 ATAGCT..............TCAGC -r003 ttagctTAGGC -r001/2 CAGCGGCAT The corresponding SAM format is:2 1Charset ANSI X3.4-1968 as defined in RFC1345. -

Lexing and Parsing with ANTLR4

Lab 2 Lexing and Parsing with ANTLR4 Objective • Understand the software architecture of ANTLR4. • Be able to write simple grammars and correct grammar issues in ANTLR4. EXERCISE #1 Lab preparation Ï In the cap-labs directory: git pull will provide you all the necessary files for this lab in TP02. You also have to install ANTLR4. 2.1 User install for ANTLR4 and ANTLR4 Python runtime User installation steps: mkdir ~/lib cd ~/lib wget http://www.antlr.org/download/antlr-4.7-complete.jar pip3 install antlr4-python3-runtime --user Then in your .bashrc: export CLASSPATH=".:$HOME/lib/antlr-4.7-complete.jar:$CLASSPATH" export ANTLR4="java -jar $HOME/lib/antlr-4.7-complete.jar" alias antlr4="java -jar $HOME/lib/antlr-4.7-complete.jar" alias grun='java org.antlr.v4.gui.TestRig' Then source your .bashrc: source ~/.bashrc 2.2 Structure of a .g4 file and compilation Links to a bit of ANTLR4 syntax : • Lexical rules (extended regular expressions): https://github.com/antlr/antlr4/blob/4.7/doc/ lexer-rules.md • Parser rules (grammars) https://github.com/antlr/antlr4/blob/4.7/doc/parser-rules.md The compilation of a given .g4 (for the PYTHON back-end) is done by the following command line: java -jar ~/lib/antlr-4.7-complete.jar -Dlanguage=Python3 filename.g4 or if you modified your .bashrc properly: antlr4 -Dlanguage=Python3 filename.g4 2.3 Simple examples with ANTLR4 EXERCISE #2 Demo files Ï Work your way through the five examples in the directory demo_files: Aurore Alcolei, Laure Gonnord, Valentin Lorentz. 1/4 ENS de Lyon, Département Informatique, M1 CAP Lab #2 – Automne 2017 ex1 with ANTLR4 + Java : A very simple lexical analysis1 for simple arithmetic expressions of the form x+3. -

Compiler Design

CCOOMMPPIILLEERR DDEESSIIGGNN -- PPAARRSSEERR http://www.tutorialspoint.com/compiler_design/compiler_design_parser.htm Copyright © tutorialspoint.com In the previous chapter, we understood the basic concepts involved in parsing. In this chapter, we will learn the various types of parser construction methods available. Parsing can be defined as top-down or bottom-up based on how the parse-tree is constructed. Top-Down Parsing We have learnt in the last chapter that the top-down parsing technique parses the input, and starts constructing a parse tree from the root node gradually moving down to the leaf nodes. The types of top-down parsing are depicted below: Recursive Descent Parsing Recursive descent is a top-down parsing technique that constructs the parse tree from the top and the input is read from left to right. It uses procedures for every terminal and non-terminal entity. This parsing technique recursively parses the input to make a parse tree, which may or may not require back-tracking. But the grammar associated with it ifnotleftfactored cannot avoid back- tracking. A form of recursive-descent parsing that does not require any back-tracking is known as predictive parsing. This parsing technique is regarded recursive as it uses context-free grammar which is recursive in nature. Back-tracking Top- down parsers start from the root node startsymbol and match the input string against the production rules to replace them ifmatched. To understand this, take the following example of CFG: S → rXd | rZd X → oa | ea Z → ai For an input string: read, a top-down parser, will behave like this: It will start with S from the production rules and will match its yield to the left-most letter of the input, i.e. -

Compiler Construction

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Compiler Construction An 18-lecture course Alan Mycroft Computer Laboratory, Cambridge University http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/users/am/ Lent Term 2007 Compiler Construction 1 Lent Term 2007 Course Plan UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Part A : intro/background Part B : a simple compiler for a simple language Part C : implementing harder things Compiler Construction 2 Lent Term 2007 A compiler UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE A compiler is a program which translates the source form of a program into a semantically equivalent target form. • Traditionally this was machine code or relocatable binary form, but nowadays the target form may be a virtual machine (e.g. JVM) or indeed another language such as C. • Can appear a very hard program to write. • How can one even start? • It’s just like juggling too many balls (picking instructions while determining whether this ‘+’ is part of ‘++’ or whether its right operand is just a variable or an expression ...). Compiler Construction 3 Lent Term 2007 How to even start? UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE “When finding it hard to juggle 4 balls at once, juggle them each in turn instead ...” character -token -parse -intermediate -target stream stream tree code code syn trans cg lex A multi-pass compiler does one ‘simple’ thing at once and passes its output to the next stage. These are pretty standard stages, and indeed language and (e.g. JVM) system design has co-evolved around them. Compiler Construction 4 Lent Term 2007 Compilers can be big and hard to understand UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Compilers can be very large. In 2004 the Gnu Compiler Collection (GCC) was noted to “[consist] of about 2.1 million lines of code and has been in development for over 15 years”. -

AST Indexing: a Near-Constant Time Solution to the Get-Descendants-By-Type Problem Samuel Livingston Kelly Dickinson College

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Honors Theses By Year Student Honors Theses 5-18-2014 AST Indexing: A Near-Constant Time Solution to the Get-Descendants-by-Type Problem Samuel Livingston Kelly Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_honors Part of the Software Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Samuel Livingston, "AST Indexing: A Near-Constant Time Solution to the Get-Descendants-by-Type Problem" (2014). Dickinson College Honors Theses. Paper 147. This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AST Indexing: A Near-Constant Time Solution to the Get-Descendants-by-Type Problem by Sam Kelly Submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors Requirements for the Computer Science Major Dickinson College, 2014 Associate Professor Tim Wahls, Supervisor Associate Professor John MacCormick, Reader Part-Time Instructor Rebecca Wells, Reader April 22, 2014 The Department of Mathematics and Computer Science at Dickinson College hereby accepts this senior honors thesis by Sam Kelly, and awards departmental honors in Computer Science. Tim Wahls (Advisor) Date John MacCormick (Committee Member) Date Rebecca Wells (Committee Member) Date Richard Forrester (Department Chair) Date Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Dickinson College April 2014 ii Abstract AST Indexing: A Near-Constant Time Solution to the Get- Descendants-by-Type Problem by Sam Kelly In this paper we present two novel abstract syntax tree (AST) indexing algorithms that solve the get-descendants-by-type problem in near constant time. -

Advanced Parsing Techniques

Advanced Parsing Techniques Announcements ● Written Set 1 graded. ● Hard copies available for pickup right now. ● Electronic submissions: feedback returned later today. Where We Are Where We Are Parsing so Far ● We've explored five deterministic parsing algorithms: ● LL(1) ● LR(0) ● SLR(1) ● LALR(1) ● LR(1) ● These algorithms all have their limitations. ● Can we parse arbitrary context-free grammars? Why Parse Arbitrary Grammars? ● They're easier to write. ● Can leave operator precedence and associativity out of the grammar. ● No worries about shift/reduce or FIRST/FOLLOW conflicts. ● If ambiguous, can filter out invalid trees at the end. ● Generate candidate parse trees, then eliminate them when not needed. ● Practical concern for some languages. ● We need to have C and C++ compilers! Questions for Today ● How do you go about parsing ambiguous grammars efficiently? ● How do you produce all possible parse trees? ● What else can we do with a general parser? The Earley Parser Motivation: The Limits of LR ● LR parsers use shift and reduce actions to reduce the input to the start symbol. ● LR parsers cannot deterministically handle shift/reduce or reduce/reduce conflicts. ● However, they can nondeterministically handle these conflicts by guessing which option to choose. ● What if we try all options and see if any of them work? The Earley Parser ● Maintain a collection of Earley items, which are LR(0) items annotated with a start position. ● The item A → α·ω @n means we are working on recognizing A → αω, have seen α, and the start position of the item was the nth token. ● Using techniques similar to LR parsing, try to scan across the input creating these items.