How the Battle of the Alamo and the Cart Wars Shaped What It Means To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Allied Powers; the Central What Did Citizens Think the U.S

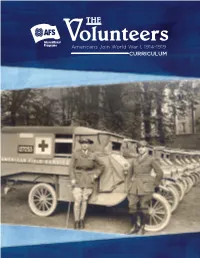

Connecting lives. Sharing cultures. Dear Educator, Welcome to The Volunteers: Americans Join World War I, 1914-1919 Curriculum! Please join us in celebrating the release of this unique and relevant curriculum about U.S. American volunteers in World War I and how volunteerism is a key component of global competence and active citizenship education today. These free, Common Core and UNESCO Global Learning-aligned secondary school lesson plans explore the motivations behind why people volunteer. They also examine character- istics of humanitarian organizations, and encourage young people to consider volunteering today. AFS Intercultural Programs created this curriculum in part to commemorate the 100 year history of AFS, founded in 1915 as a volunteer U.S. American ambulance corps serving alongside the French military during the period of U.S. neutrality. Today, AFS Intercultural Programs is a non-profit, intercultural learn- ing and student exchange organization dedicated to creating active global citizens in today’s world. The curriculum was created by AFS Intercultural Programs, together with a distinguished Curriculum Development Committee of historians, educators, and archivists. The lesson plans were developed in partnership with the National World War I Museum and Memorial and the curriculum specialists at Pri- mary Source, a non-profit resource center dedicated to advancing global education. We are honored to have received endorsement for the project from the United States World War I Centennial Commission. We would like to thank the AFS volunteers, staff, educators, and many others who have supported the development of this curriculum and whose daily work advances the AFS mission. We encourage sec- ondary school teachers around the world to adapt these lesson plans to fit their classroom needs- les- sons can be applied in many different national contexts. -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, September 29, 1997 Volume 33ÐNumber 39 Pages 1371±1429 1 VerDate 22-AUG-97 07:53 Oct 01, 1997 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 W:\DISC\P39SE4.000 p39se4 Contents Addresses and Remarks Communications to CongressÐContinued See also Meetings With Foreign Leaders Future free trade area negotiations, letter Arkansas, Little Rock transmitting reportÐ1423 Congressional Medal of Honor Society India-U.S. extradition treaty and receptionÐ1419 documentation, message transmittingÐ1401 40th anniversary of the desegregation of Iraq, letter reportingÐ1397 Central High SchoolÐ1416 Ireland-U.S. taxation convention and protocol, California message transmittingÐ1414 San Carlos, roundtable discussion at the UNITA, message transmitting noticeÐ1414 San Carlos Charter Learning CenterÐ 1372 Communications to Federal Agencies San Francisco Contributions to the International Fund for Democratic National Committee Ireland, memorandumÐ1396 dinnerÐ1382 Funding for the African Crisis Response Democratic National Committee luncheonÐ1376 Initiative, memorandumÐ1397 Saxophone Club receptionÐ1378 Interviews With the News Media New York City, United Nations Exchange with reporters at the United LuncheonÐ1395 Nations in New York CityÐ1395 52d Session of the General AssemblyÐ1386 Interview on the Tom Joyner Morning Show Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh in Little RockÐ1423 AFL±CIO conventionÐ1401 Democratic National Committee luncheonÐ1408 Letters and Messages Radio addressÐ1371 50th anniversary of the National Security Council, messageÐ1396 Communications to Congress Meetings With Foreign Leaders Angola, message reportingÐ1414 Russia, Foreign Minister PrimakovÐ1395 Canada-U.S. taxation convention protocol, message transmittingÐ1400 Notices Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty and Continuation of Emergency With Respect to documentation, message transmittingÐ1390 UNITAÐ1413 (Continued on the inside of the back cover.) Editor's Note: The President was in Little Rock, AR, on September 26, the closing date of this issue. -

Yankees Who Fought for the Maple Leaf: a History of the American Citizens

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 12-1-1997 Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917 T J. Harris University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Harris, T J., "Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917" (1997). Student Work. 364. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/364 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Yankees Who Fought For The Maple Leaf’ A History of the American Citizens Who Enlisted Voluntarily and Served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force Before the United States of America Entered the First World War, 1914-1917. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by T. J. Harris December 1997 UMI Number: EP73002 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Hispanic-Americans and the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar History Theses and Dissertations History Spring 2020 INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) Carlos Nava [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_etds Recommended Citation Nava, Carlos, "INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939)" (2020). History Theses and Dissertations. 11. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_etds/11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) Approved by: ______________________________________ Prof. Neil Foley Professor of History ___________________________________ Prof. John R. Chávez Professor of History ___________________________________ Prof. Crista J. DeLuzio Associate Professor of History INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Dedman College Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in History by Carlos Nava B.A. Southern Methodist University May 16, 2020 Nava, Carlos B.A., Southern Methodist University Internationalism in the Barrios: Hispanic-Americans in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) Advisor: Professor Neil Foley Master of Art Conferred May 16, 2020 Thesis Completed February 20, 2020 The ripples of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) had a far-reaching effect that touched Spanish speaking people outside of Spain. -

Sicilian Americans Have Something to Say, in Sicilian

Sicilian Americans Have Something to Say, in Sicilian Every Wednesday night, a small group of students gather for their language course at the Italian Charities of America Inc. in Flushing, Queens. Ironically, the students are not interested in learning Italian, but a separate language that arrived during the wave of Italian immigration to New York City. These students are the children and grandchildren of Sicilian immigrants. “We only write the phrases on the board in Sicilian, not in Italian, so that is what stays in our memories after class,” says Salvatore Cottone, teacher of the Sicilian language class. On the chalkboard, Cottone has written, “Dumani Marialena sinni va cu zitu.” If he were to compare it to Italian, it would say “Marialena andrà con il suo ragazzo.” It would not help the students to observe the ways that one language relates to the other; they are completely separate in form, construction, and syntax. Sicilian and Italian are both audibly and visibly diverse. To note a few examples, Sicilian uses different vowel sounds, relying on a long “u” rather than the “o” as in “trenu” (train) and “libbru” (book) instead of “treno” and “libro.” There is no future tense verb conjugation; instead, context words such as tomorrow, “dumani,” and later, “doppu,” are used to indicate that the action will take place in the future. The cadence and pronunciation of Sicilian also demonstrate obvious differences from the standard Italian. Scholars have found that Sicilian was the first written language in Italy after Latin. Declared by UNESCO as the first romance language of Europe, Sicilian contains a unique vocabulary of over 250,000 words. -

Have German Will Travel Feiertag

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL FEIERTAG "Bei uns ist immer was los!" AUSTRIAN-AMERICAN DAY: der 26. September W ILLIAM J. CLINTON XUJ Pmidmtoftht Uniud Sltlte: 1993-2001 Proclamation 7027- Austrian-American Day, 1997 September 25. 1997 By the President of the United States ofAmerica A Proclamation For more than 2.00 years, the life of our Nation has been enriched and renewed by the many people who have come here from around the world, s~oeking a new life for Lhcmsclvcs aod their families. Austrian America us have made their own unique and lastiug contributions to America's strength and character, and they contin,l<ltO play a vital role in tho peace and prosperity we enjoy today. As with so many other immigrants, the e.1ruest Austrians came to America in search of religious freedom. Arrhing in 1734, they settled in the colony of Georgia, f.TOwing and pros pering with the passing of the years. One of these early Austrian settlers, J ohann Adam Treutleo, was to become the Hrs t elected go-nor of the new State of Georgia. lJlthe two ecoturies that foUowed, millions of other Austrians made the same journey to our shores. From the political refugees o f the 1848 re>-olutions in Austria to Jews Oceing the anti-Semitism of Hitler's Third Reich, Austrians brought ";th them to America a lo\e of freedom, a strong work ethic, and a deep re--erence for educatioiL In C\'Cf'Y fldd of endeavor, Austrian Americans ha\'C made notable contributions to our culture and society. -

CHAPTER 1 SPECIAL AGENTS, SPECIAL THREATS: Creating the Office of the Chief Special Agent, 1914-1933

CHAPTER 1 SPECIAL AGENTS, SPECIAL THREATS: Creating the Office of the Chief Special Agent, 1914-1933 CHAPTER 1 8 SPECIAL AGENTS, SPECIAL THREATS Creating the Office of the Chief Special Agent, 1914-1933 World War I created a diplomatic security crisis for the United States. Under Secretary of State Joseph C. Grew afterwards would describe the era before the war as “diplomatic serenity – a fool’s paradise.” In retrospect, Grew’s observation indicates more the degree to which World War I altered how U.S. officials perceived diplomatic security than the actual state of pre-war security.1 During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Department had developed an effective set of security measures; however, those measures were developed during a long era of trans-Atlantic peace (there had been no major multi-national wars since Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1814). Moreover, those measures were developed for a nation that was a regional power, not a world power exercising influence in multiple parts of the world. World War I fundamentally altered international politics, global economics, and diplomatic relations and thrust the United States onto the world stage as a key world power. Consequently, U.S. policymakers and diplomats developed a profound sense of insecurity regarding the content of U.S. Government information. The sharp contrast between the pre- and post-World War I eras led U.S. diplomats like Grew to cast the pre-war era in near-idyllic, carefree terms, when in fact the Department had developed several diplomatic security measures to counter acknowledged threats. -

PROCLAMATION 7026—SEPT. 19, 1997 111 STAT. 2981 National

PROCLAMATION 7026—SEPT. 19, 1997 111 STAT. 2981 Proclamation 7026 of September 19, 1997 National Farm Safety and Health Week, 1997 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation From the earliest days of our Nation, the men and women who work the land have held a special place in America's heart, history, and economy. Many of us are no more than a few generations removed from forebears whose determination and hard work on farms and fields helped to build our Nation and shape its values. While the portion of our population directly involved in agriculture has diminished over the years, those who live and work on America's farms and ranches continue to make extraordinary contributions to the quality of our na tional life and the strength of our economy. The life of a farmer or rancher has never been easy. The work is hard, physically challenging, and uniquely subject to the forces of nature; the chemicals and labor-saving machinery that have helped American farmers become so enormously productive have also brought with them new health hazards; and working with livestock can result in fre quent injury to agricultural workers and their families. Fortunately, there are measures we can take to reduce agriculture-relat ed injuries, illnesses, and deaths. Manufacturers continue to improve the safety features of farming equipment; protective clothing and safety gear can reduce the exposure of workers to the health threats posed by chemicals, noise, dust, and sun; training in first-aid procedures and ac cess to good health care can often mean the difference between life and death. -

Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible To

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2012-12-12 Austro-American Reflections: Making the ritingsW of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen Andrew Simon Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Simon, Stephen Andrew, "Austro-American Reflections: Making the ritingsW of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 3543. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3543 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen A. Simon A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Robert McFarland, Chair Michelle James Cindy Brewer Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages Brigham Young University December 2012 Copyright © 2012 Stephen A. Simon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen A. Simon Department of German Studies and Slavic Languages, BYU Master of Arts Ann Tizia Leitich wrote about America to a Viennese audience as a foreign correspondent with the unique and personal perspective of an immigrant to the United States. Leitich differentiates herself from other Europeans who reported on America in her day by telling of the life of the average working American. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

American Studies 1981-2000

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. Twenty-Year Index, Yearbook of German- American Studies 1981-2000 by William D. Keel 2000 This is the published version of the article, made available with the permission of the publisher. Keel, William D. “Twenty-Year Index, Yearbook of German-American Studies 1981-2000,” Yearbook of German-American Studies 35 (2000): 265-303. Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. Yearbook of German-American Studies Twenty-Year Index: Volumes 16-35 (1981-2000) Articles, Review Essays, and Book Reviews William D. Keel, Editor The twenty-year index combines the two earlier indexes for the Yearbook of 1985 and 1992 with those items published from 1993 to 2000. Its format follows that of the 1992 index beginning with an alphabetical listing by author of articles. This is followed by a separate listing for bibliographical and review essays. A third listing contains books reviewed, alphabetized by authors of books. An alphabetical index of authors of book reviews together with co-authors of articles follows. The topical index covers both articles and book reviews and utilizes the topical index of the two earlier published indexes as its basis. I. Articles 1. Adams, Willi Paul. 1997. "Amerikanische Verfassungsdiskussion in deutscher Sprache: Politische Begriffe in Texten der deutschamerikanischen Aufklarung, 1761-88." 32:1-20. 2. Arndt, Karl J. R. 1981. "Schliemann's Excavation of Troy and American Politics, or Why the Smithsonian Institution Lost Sdbliemann's Great Troy Collection to Berlin." 16:1-8. -

A Comparative Study of America's Entries Into World War I and World War II

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2009 A Comparative Study of America's Entries into World War I and World War II. Samantha Alisha Taylor East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Samantha Alisha, "A Comparative Study of America's Entries into World War I and World War II." (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1860. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1860 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Comparative Study of America's Entries into World War I and World War II _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _____________________ by Samantha Alisha Taylor May 2009 _____________________ Stephen Fritz, Chair Elwood Watson Ronnie Day Keywords: World War One, World War Two, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, American Entry ABSTRACT A Comparative Study of America's Entries into World War I and World War II by Samantha Alisha Taylor This thesis studies events that preceded America‟s entries into the First and Second World Wars to discover similarities and dissimilarities.