A Critical Study of Jabir Ibn Hayy&N's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Al-Fiabbas, 103, 108 Fiabbas I, Shah, 267 Fiabbasids, 84, 113–15

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-58214-8 - The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600–1800 Jonathan P. Berkey Index More information Index al-fiAbbas, 103, 108 Akhbaris, 268 fiAbbas I, Shah, 267 Alamut, 193, 194 fiAbbasids, 84, 113–15, 141–2, 143, 169, Aleppo, 190, 191, 200–01, 212, 255 170, 189 Alexandria, 23, 24 as caliphs, 124–9, 182 destruction of the Serapeum in, 21 caliphate in Cairo, 182, 204, 210 Jews in, 11 decline of, 203–4 madrasas in, 197–8 revolt of, 103–9 fiAli al-Hadi, 133 Sunnism and, 149 fiAli al-Karaki, 267, 268 see also: Shifiis, Shifiism; Sunnism fiAli al-Rida, 133 fiAbdallah ibn Mufiawiya, 84 fiAli ibn fiAbdallah ibn al-fiAbbas, 104 fiAbdallah ibn al-Mubarak, 120, 154 fiAli ibn Abi Talib, 71, 86, 96, 141–2 fiAbdallah ibn Saba√, 95 Ismafiili view of, 138–9 fiAbd al-Ghani al-Nabulusi, 265 murder of, 76 fiAbd al-Malik, 59, 80–1, 86 Shifiis view as Muhmmad’s rightful Abraham, 48–9, 67, 80, 82 successor, 70, 84, 87, 95, 130–2, Abu√l-fiAbbas, 108 135–6, 142 Abu Bakr, 70–1, 79, 132, 142 Sufism and, 152, 234, 246 Abu Hanifa, 144, 165 veneration, by Sunnis, 142 Abu Hashim ibn Muhammad ibn fiAli ibn Maymun al-Idrisi, 202 al-Hanafiyya, 104, 108 fiAli Zayn al-fiAbidin, 174 Abu Hurayra, 96 Allat, 42, 44 Abu fiIsa al-Isfahani, 94–5 Alp Arslan, 180, 217 Abu Muslim, 104, 107–8, 124, 172, fiamma, 254–7 174–5 fiAnan ben David, 165–6 Abu Salama, 124 Anatolia, 181–2, 195, 196, 208, 233, 235, Abu√l-Sufiud Efendi, 263–4 245–7, 252, 266 Abu Yazid al-Bistami, 153, 156 Antioch, 11–12, 19, 23, 51 Abu Yusuf, 148 al-Aqsa mosque, 200 al-Afdal ibn Badr al-Jamali, 197 Arabia al-Afshin, 163, 164, 174–5 Jews and Judaism in, 46–9, 94–6, 164 ahl al-bayt, 88, 107–8, 124, 130, 132 Kharijism in, 86 Ahmad ibn Hanbal, 125, 127, 144, 146, origins of Islam in, 61–9 148, 149, 150 pre-Islamic, 39–49 Ahmad ibn Tulun, 115 religion in, 41–9, 52–3 276 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-58214-8 - The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600–1800 Jonathan P. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Full-Text (PDF)

Vol. 16(8), pp. 336-342, August, 2021 DOI: 10.5897/ERR2021.4179 Article Number: B7753C367459 ISSN: 1990-3839 Copyright ©2021 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Educational Research and Reviews http://www.academicjournals.org/ERR Review Scholars and educational positions under criticism and praise in the Medieval Islamic Era Hatim Muhammad Mahamid* and Younis Fareed Abu Al-Haija Department of Education, Faculty of Management and Organization of Education Systems, Sakhnin College for Teachers' Education, Isreal. Received 14 June 2021, Accepted 28 July 2021 This research focuses on criticism and praise in Arabic literature, history and poetry towards those in charge of the scientific movement in the Medieval Era. The research method was theoretical and qualitative. Many poets and scholars praised the rulers and sultans who established mosques and other educational institutions (madrasa-s) based on endowments, which had a role in sciences, intellectual and religious renaissance. They were subject to criticism or praise for their work or the educational role they followed. The topics of praise to the ulama centered on, their diligence and dissemination of science, as well as of their behavior and moral manners. On the other hand, the criticism of poetry centered on the mistakes of some scholars, their scientific stances in religious matters and criticizing scholars of the sultans for their attitudes in serving the rulers. Poets were also interested in criticizing scholars (ulama) who moved away from the path of morality, virtue, and shari‘a, and who lead the teaching without qualification or mismanagement of the educational process; and therefore do not preserve the rules of morality in lessons, education or discussions, and their lack of good morals towards students. -

Índice De Nombres Propios A

Índice de nombres propios Los números en cursiva indican fotografías Abu.Muhammad (dai nizaríta), 195 Abu.Muslim. (Abdal.Arman.ibn.Muslim.al. A Jurassaní ), 51, 52, 53, 321, Abú.Raqwa, (Ibn.W alid.Hishames), 120, 121, Abass.I, el grande, safawiya., 219 331 Abd.Alá, padre de Mahoma, 317 Abu.Said.al.Hassan.ibn.Bahran.al.Jannabi Abd.Al.Baha, (bahai), 227, 230 (qármata), 86, Abd.Al.Kaim.Ha´iri, Sheik (ayatollah), 232 Abu.Soleiman.al.Busti, (ilwan al.saffa), 324 Abd.al.Malik.ibn.Attash, 161 Abu.Tahir.al.saigh (dai nizaríta sirio), 187, 188 Abd.Al.Mumin, (califa almohade), 49, 319 Abu.Tahir.ibn.Abú.Said (qármata), 86, 87 Abd.Al.Rahman, II, andalusí, 328 Abu.Tahir.al.Saigh —el orfebre“ (dai nizaríta), Abd.Al.Rahman III, califa de Al.Andalus, 321, 187, 188 328 Abú.Talib (padre de Alí), 31, 40, 43, Abdalláh, hermano de Nizar, 143, 144 Abu.Yacid, 101 Abdalláh.abu.Abass, califa abasida , 52, 64 Abud.al.Dawla, buyíes, 57 Abdalláh.al.Taashi, (califa ansarí), 342 Abul.Abbas.ibn.Abu.Muhammad, 92,93, 95, Abdalláh.al.Tanuji (drusos), 133 96 Abdalláh.ibn.Maimún (Imam fatimíta), 85 Abul.al.de.Bahlul, 89, 108 Abdalláh.Qatari (Mahdi), 264 Abul.Ala.al.Maari, 17 Abdan (qármata), 85, 86 Abul.Fazal.Raydam, 112 Abdel.Aziz.al.Rantisi, Hamas, 357 Abul.Hussein, dai ismailíta, 93 Abderrazac.Amari, Al.Qaida, 319 Abul.ibn.Abbas.Awan.Hanbali, 117 Abdul.Majid.II.(califa turco), 242 Abul.ibn.Hussein.al.Aswad (dai fatimíta), 91, Abdul.Malik.al.Ashrafani (drusos), 127 92 Abdul.Qafs, (qármata), 86 Abul.Kassim.ibn.Abú.Said (qármata), 86, 87, Abdul.Raman.ibn.Mulyam, jariyita, -

Proquest Dissertations

The history of the conquest of Egypt, being a partial translation of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam's "Futuh Misr" and an analysis of this translation Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hilloowala, Yasmin, 1969- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:08:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282810 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectiotiing the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Islamic Civilization in Spain

Psychiatria Danubina, 2017; Vol. 29, Suppl. 1, pp 64-72 Conference paper © Medicinska naklada - Zagreb, Croatia ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION IN SPAIN – A MAGNIFICIENT EXAMPLE OF INTERACTION AND UNITY OF RELIGION AND SCIENCE Safvet Halilović Faculty of Islamic Education of the University in Zenica, Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina SUMMARY Islam and its followers had created a civilization that played very important role on the world stage for more than a thousand years. One of the most important specific qualities of the Islamic civilization is that it is a well-balanced civilization that brought together science and faith, struck a balance between spirit and matter and did not separate this world from the Hereafter. This is what distinguishes the Islamic civilization from other civilizations which attach primary importance to the material aspect of life, physical needs and human instincts, and attach greater attention to this world by striving to instantly satisfy desires of the flesh, without finding a proper place for God and the Hereafter in their philosophies and education systems. The Islamic civilization drew humankind closer to God, connected the earth and heavens, subordinated this world to the Hereafter, connected spirit and matter, struck a balance between mind and heart, and created a link between science and faith by elevating the importance of moral development to the level of importance of material progress. It is owing to this that the Islamic civilization gave an immense contribution to the development of global civilization. Another specific characteristic of the Islamic civilization is that it spread the spirit of justice, impartiality and tolerance among people. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Extract from the Poison Edition

The Book of the Treasure of Alexander The Poison Edition Translated by Nicholaj de Mattos Frisvold and Edited by Christopher Warnock, Esq. Copyright © 2010 Nicholaj de Mattos Frisvold and Christopher Warnock All Rights Reserved Contents Occult Virtue & Hermetic Philosophy 1 Alexander, Aristotle & Hermes Trismegistus 4 Notes on the Translation 5 Ibn Wahshiyya & the Poison Edition 6 Warning and Disclaimer 7 The First Art The Chapter of the Formation of Things 16 The Chapter about the Indications of the Two Benefic Stars 16 The Chapter about the Greater Luminary 17 The Second Art of the Process of Elaboration and Manipulation of the Three Elixirs Section on the Extraction of the Active Water, called Sapius 25 Extraction of the Second Water called Qurial 25 Extraction of the Third Water called Rarasius 26 Extraction of the Fourth Water that is extremely useful and is called Triras 26 Chapter about the Extraction of the Essence Deposited in the Strength of Mars 27 Chapter about the Purification of Arsenic 29 Another Chapter about the Purification of Arsenic, which is Easier than the First 29 Chapter of the Sublimation of the Purified Arsenic 30 Chapter of the Purification of Copper 30 Chapter about How to make it Whitish and make it look like Silver being what was Bequeathed by Hermes and to what Balinas also Dedicated himself 31 Chapter about the other Method of Whitening of Copper 31 Chapter about How to Soften Purified Copper 32 Recipe of the Great Softener Water to which Hermes called Kalianus, that means ‘the one that takes out dryness’ -

The Jewish Discovery of Islam

The Jewish Discovery of Islam The Jewish Discovery of Islam S tudies in H onor of B er nar d Lewis edited by Martin Kramer The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University T el A v iv First published in 1999 in Israel by The Moshe Dayan Cotter for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University Tel Aviv 69978, Israel [email protected] www.dayan.org Copyright O 1999 by Tel Aviv University ISBN 965-224-040-0 (hardback) ISBN 965-224-038-9 (paperback) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Publication of this book has been made possible by a grant from the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation. Cover illustration: The Great Synagogue (const. 1854-59), Dohány Street, Budapest, Hungary, photograph by the late Gábor Hegyi, 1982. Beth Hatefiitsoth, Tel Aviv, courtesy of the Hegyi family. Cover design: Ruth Beth-Or Production: Elena Lesnick Printed in Israel on acid-free paper by A.R.T. Offset Services Ltd., Tel Aviv Contents Preface vii Introduction, Martin Kramer 1 1. Pedigree Remembered, Reconstructed, Invented: Benjamin Disraeli between East and West, Minna Rozen 49 2. ‘Jew’ and Jesuit at the Origins of Arabism: William Gifford Palgrave, Benjamin Braude 77 3. Arminius Vámbéry: Identities in Conflict, Jacob M. Landau 95 4. Abraham Geiger: A Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reformer on the Origins of Islam, Jacob Lassner 103 5. Ignaz Goldziher on Ernest Renan: From Orientalist Philology to the Study of Islam, Lawrence I. -

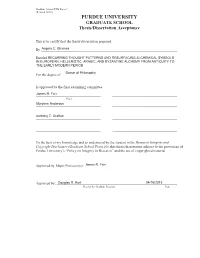

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Alchemylab Articles\374

Alchemical Theory The One Thing (or the Subtle Ether) Space, whether interplanetary, inner matter, or inter-organic, is filled with a subtle presence emanating from the One Thing of the universe. Later alchemists called it, as did the ancients, the subtle Ether. This primordial fluid or fabric of space pervades everything and all matter. Metal, mineral, tree, plant, animal, man; each is charged with the Ether in varying degrees. All life on the planet is charged in like manner; a world is built up in this fluid and move through a sea of it. Alchemical Ether, which some Hermeticists call the Astral Light, determines the constitution of bodies. Hardness and softness, solidity and liquidity, all depend on the relative proportion of ethereal and ponderable matter of which they me composed. The arbitrary division and classification of physical science, the whole range of physical phenomena, proceeds from the primary Ether, for science has reduced matter as we know it to nothing but Ether, which, although not solid matter, is still matter, the First Matter of the alchemists. When most of us speak of matter, of course, we usually visualize solid substance, but it has been proved by that matter is not actually solid, but merely a stress, a strain in the etheric field of time and space. The atom and the electrons and protons of which it is composed, all move in a sea of Ether, so, that in accordance with this theory of alchemy, the very air we breathe, the very bodies we inhabit, all things most likewise be moving in this sea of Ether, the parent element from which all manifestation has come.