The Half-Life of Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leisure Pass Group

Explorer Guidebook Empire State Building Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Advanced reservations are required. You will not be able to enter the Observatory without a timed reservation. Please visit the Empire State Building's website to book a date and time. You will need to have your pass number to hand when making your reservation. Getting in: please arrive with both your Reservation Confirmation and your pass. To gain access to the building, you will be asked to present your Empire State Building reservation confirmation. Your reservation confirmation is not your admission ticket. To gain entry to the Observatory after entering the building, you will need to present your pass for scanning. Please note: In light of COVID-19, we recommend you read the Empire State Building's safety guidelines ahead of your visit. Good to knows: Free high-speed Wi-Fi Eight in-building dining options Signage available in nine languages - English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin Hours of Operation From August: Daily - 11AM-11PM Closings & Holidays Open 365 days a year. Getting There Address 20 West 34th Street (between 5th & 6th Avenue) New York, NY 10118 US Closest Subway Stop 6 train to 33rd Street; R, N, Q, B, D, M, F trains to 34th Street/Herald Square; 1, 2, or 3 trains to 34th Street/Penn Station. The Empire State Building is walking distance from Penn Station, Herald Square, Grand Central Station, and Times Square, less than one block from 34th St subway stop. Top of the Rock Observatory Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Getting In: Use the Rockefeller Plaza entrance on 50th Street (between 5th and 6th Avenues). -

EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers

TM EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers, Top of the RockTM at Rockefeller Center is an exciting destination for New York City students. Located on the 67th, 69th, and 70th floors of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, the Top of the Rock Observation Deck reopened to the public in November 2005 after being closed for nearly 20 years. It provides a unique educational opportunity in the heart of New York City. To support the vital work of teachers and to encourage inquiry and exploration among students, Tishman Speyer is proud to present Top of the Rock Education Materials. In the Teacher Guide, you will find discussion questions, a suggested reading list, and detailed plans to help you make the most of your visit. The Student Activities section includes trip sheets and student sheets with activities that will enhance your students’ learning experiences at the Observation Deck. These materials are correlated to local, state, and national curriculum standards in Grades 3 through 8, but can be adapted to suit the needs of younger and older students with various aptitudes. We hope that you find these education materials to be useful resources as you explore one of the most dazzling places in all of New York City. Enjoy the trip! Sincerely, General Manager Top of the Rock Observation Deck 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York NY 101 12 T: 212 698-2000 877 NYC-ROCK ( 877 692-7625) F: 212 332-6550 www.topoftherocknyc.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Teacher Guide Before Your Visit . Page 1 During Your Visit . Page 2 After Your Visit . Page 6 Suggested Reading List . -

Table of Contents

CITYFEBRUARY 2013 center forLAND new york city law VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1 Table of Contents CITYLAND Top ten stories of 2012 . 1 CITY COUNCIL East Village/LES HD approved . 3 CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CPC’s 75th anniversary . 4 Durst W . 57th street project . 5 Queens rezoning faces opposition . .6 LANDMARKSFPO Rainbow Room renovation . 7 Gage & Tollner change denied . 9 Bed-Stuy HD proposed . 10 SI Harrison Street HD heard . 11 Plans for SoHo vacant lot . 12 Special permits for legitimate physical culture or health establishments are debated in CityLand’s guest commentary by Howard Goldman and Eugene Travers. See page 8 . Credit: SXC . HISTORIC DISTRICTS COUNCIL CITYLAND public school is built on site. HDC’s 2013 Six to Celebrate . 13 2. Landmarking of Brincker- hoff Cemetery Proceeds to Coun- COURT DECISIONS Top Ten Stories Union Square restaurant halted . 14. cil Vote Despite Owner’s Opposi- New York City tion – Owner of the vacant former BOARD OF STANDARDS & APPEALS Top Ten Stories of 2012 cemetery site claimed she pur- Harlem mixed-use OK’d . 15 chased the lot to build a home for Welcome to CityLand’s first annual herself, not knowing of the prop- top ten stories of the year! We’ve se- CITYLAND COMMENTARY erty’s history, and was not compe- lected the most popular and inter- Ross Sandler . .2 tently represented throughout the esting stories in NYC land use news landmarking process. from our very first year as an online- GUEST COMMENTARY 3. City Council Rejects Sale only publication. We’ve been re- Howard Goldman and of City Property in Hopes for an Eugene Travers . -

Boston City Hall: Conception and Reception

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Boston City Hall: Conception and Reception in the Era of Civil Defense ! ! Angie! Jo HAA 98br: Advanced Tutorial: Methods of Architectural History December! 15, 2014 Instructor: David Sadighian !1 Boston City Hall: Conception and Reception in the Era of Civil Defense ! . there is no such thing as a merely given, or simply available, starting point: beginnings have to be made for each project in such a way as to enable what follows from them. The idea of beginning, indeed the act of beginning, necessarily involves an act of delimitation by which something is cut out of a great mass of material, separated from the mass, and made to stand for, as well as be, a starting point, a beginning. ! - Edward Said, Orientalism Introduction Boston City Hall has been equally described as beautiful and monstrous, a fortress, a bunker, intimidating, dignified, a waste of space, and the greatest use of space, in a passionate and polarizing struggle of reception from its design in 1962, to its current state in 2014. Its conception is often attributed to human actors—the architects Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles and the competition jury that chose their design—and the intentions of character and resolve, articulated governance, and openness to civic life that they proposed on paper long before any building went up. These intentions have nearly always been described as abstract ideals removed from any particular political situation that may necessitate such “character and resolve.” There was not a word mentioned, either in the commission or in the architects’ statements, of the political nature of the civic project, nor the national and international tensions of the time—non-human actors that inevitably had a hand in the making of Boston City Hall, but have rarely been addressed. -

The Graduate School and University Center of the City University of New York Ph.D

The Graduate School and University Center of The City University of New York Ph.D. Program in Art History FALL 2003 - COURSE DESCRIPTIONS N.B. Lecture classes are limited to 20 students, Methods of Research is limited to 15 and seminar classes are limited to 12 students. Three overtallies are allowed in each class but written permission from the instructor and from the Executive Officer and/or the Deputy Executive Officer is required. ART 70000 - Methods of Research GC: Tues., 11:45 A.M.-1:45 P.M., 3 credits, Prof. Bletter, Rm. 3416, [45689] The course will examine the power of visual imagery over text first as a pre-literate, then as a populist, seemingly non-elitist system of information that dominates our culture today. It will deal with the impact of scientific rationalism (the role of perspective and axonometric projections) and Romanticism on the understanding of perception in general (Goethe, Friedrich, and Schinkel will be used as case studies). Notions of mimesis will be introduced through an analysis of the panorama, diorama, photography, and theories of polychromy. The psychological and social developments of perception and their formative influence on theory and practice of art in the nineteenth century will be stressed, as well as the impact of phenomenology and Gestalt psychology in the twentieth century. Jonathan Crary’s approach in Techniques of the Observer will be problematized through examples that contradict his thesis, such as the central place of emotive states in Charles Fourier’s social utopianism, the anti-rationalist program of the 19th c. pre-school and education reform movement (Pestalozzi, Froebel, Montessori) through its emphasis on the emotive (Cizek’s and Itten’s art classes for children in Vienna, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Froebel toys); and the influence of synaesthesia (Symbolism, Art Nouveau, Expressionism), and primitivism (Fauves, New Brutalists, etc.). -

Wurlington Press Order Form Date

Wurlington Press Order Form www.Wurlington-Bros.com Date Build Your Own Chicago postcards Build Your Own New York postcards Posters & Books Quantity @ Quantity @ Quantity @ $ Chicago’s Tallest Bldgs Poster 19" x 28" 20.00 $ $ $ Water Tower Postcard AR-CHI-1 2.00 Flatiron Building AR-NYC-1 2.00 Louis Sullivan Doors Poster 18” x 24” 20.00 $ $ $ Chicago Tribune Tower AR-CHI-2 2.00 Empire State Building AR-NYC-2 2.00 Auditorium Bldg Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ $ $ AR-NYC-3 3.5” x 5.5” Wrigley Building AR-CHI-3 2.00 Citicorp Center 2.00 John Hancock Memo Book 4.95 $ $ $ AT&T Building AR-NYC-4 2.00 Pritzker Pavilion Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 Sears Tower AR-CHI-4 2.00 $ $ Rookery Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ Chrysler Building AR-NYC-5 2.00 John Hancock Center AR-CHI-5 2.00 $ $ American Landmarks Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 $ Lever House AR-NYC-6 2.00 AR-CHI-6 Reliance Building 2.00 $ $ U.S. Capitol Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 AR-NYC-7 $ Seagram Building 2.00 Bahai Temple AR-CHI-7 2.00 $ $ Santa’s Workshop Cut & Asssemble Book 12.95 Woolworth Building AR-NYC-8 2.00 $ Marina City AR-CHI-9 2.00 Haunted House Cut & Asssemble Book $12.95 $ Lipstick Building AR-NYC-9 2.00 $ $ 860 Lake Shore Dr Apts AR-CHI-10 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Book 30.00 $ Hearst Tower AR-NYC-10 2.00 $ $ Lake Point Tower AR-CHI-11 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Zines (per issue) 2.75 $ AR-NYC-11 UN Headquarters 2.00 $ $ Flood and Flotsam Book 16.00 Crown Hall AR-CHI-12 2.00 $ 1 World Trade Center AR-NYC-12 2.00 $ AR-CHI-13 35 E. -

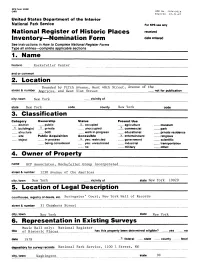

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

Personal Radios

RADIO TODAY RECIPE FOR HAPPINESS - Personal radios for GENERAL ELECTRIC TOUCH TUNING MODEL F -96 General Electric Touch Tuning -the highest development in automatic tuning -is not only sensational in performance but sensational in price. New G -E Touch Tuning series includes Model F -96 -9 tubes with 7 Touch Tuning buttons; Model F- 107 -10 tubes with 16 Touch Tuning buttons; Model F- 135-13 tubes with 16 Touch Tuning buttons; and radio - phonograph combination Model F-109 - 10 tubes with 16 Touch Tuning buttons. The General Electric Radio advertising and merchandising plan is geared to speed up your sales. And of course, each model carries a money profit worth working for. ALL OF THEM GREAT HOLIDAY NUMBERS GENERAL ELECTRIC FORRk REPLACEMENTS SPECIFY GENERAL ELECTRIC PRE- TESTED TUBES APPLIANCE AND MERCHANDISE DlPARTMENT, GENERAL ELECTRIC CO., BRIDGEPORT, CONN. elMwriZW !9 bach 1 and FIR and INSTANTANEOUS ELECTRIC Push -a- Button TUNING - .. , _:, _ r 95 $ LIST with tul! táacount Perfected button tuning, at a popular 5 -tube super, two bands, AC operation, cabinet fin - price - with FULL DEALER PROFIT isbed m light walnut, 1454' tong, 6W deep, 8%' bigb. The experience of Mr. Frank Andrea HERE'S the sec the trade has been looking for Instantaneous is among the longest and richest in all radio, dating hack to the early electric push -a -button tuning at a moderate price, yet with the pioneer days. quality that stays sold. Service expense has been out As early as 1915 Mr. Andrea was engineered of recognized as an outstanding radio this design. One look at the set will convince you it's built to guar- authority, when he was building pre- cision equipment for the United States antee consumer satisfaction. -

Theories of Architecture Lecture-11- Architecture After World War I

Theories of Architecture Lecture-11- Architecture after World War I ART DECO & Rationalism Prepared by Tara Azad Rauof 1 This lecture Context: The Origin of ART DECO Key Ideas Characteristics of ART DECO Famous Art Deco Building Rationalism Rationalism in Architecture Pioneer of Rationalism in Europe 2 ART DECO [The Origin]: Art Deco, sometimes referred to as Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture and design that first appeared in France just before World War I. Art Deco influenced the design of buildings, furniture, jewelry, fashion, cars, movie theatres, trains, ocean liners, and everyday objects such as radios and vacuum cleaners. Art Deco practitioners were often influenced by such as Cubism, De Stijl, and Futurism. Art Deco was a pastiche of many different styles, sometimes contradictory, united by a desire to be modern. From its outset, Art Deco was influenced by the bold geometric forms of Cubism and the bright colors of de Stijl. The Art Deco style originated in Paris, but has influenced architecture and culture as a whole. Art Deco works are symmetrical, geometric, streamlined, often simple, and pleasing to the eye. This style is in contrast to avant-garde art of the period Key Ideas: * Art Deco, similar to Art Nouveau, is a modern art style that attempts to infuse functional objects with artistic touches. This movement is different from the fine arts (painting and sculpture) where the art object has no practical purpose or use beyond providing interesting viewing. * With the large-scale manufacturing, artists and designers wished to enhance the appearance of mass-produced functional objects - everything from clocks to cars and buildings. -

Vol IV No 1 2018.Pages

Vol. IV, No. 1, 2018 The Chrysler Building at 405 Lexington Avenue. Created by William Van Alen, it is considered Manhattan’s “Deco monument.” See “New York City’s Art Deco Era—with Anthony W. Robins,” p. 2. Photo credit: Randy Juster. "1 Vol. IV, No. 1, 2018 Contents New York City’s Art Deco Era— with Anthony W. Robins P. 2 New York City’s Art Deco by Melanie C. Colter Era—with Anthony W. Robins, by Melanie C. Colter After the Paris World’s Fair of 1925, Art Deco and Style P. 8 R.I. Inspires the Visual Moderne principles spread rapidly across the globe. Between Arts: Edward Hopper’s 1923 and 1932, Art Deco transformed the New York City Blackwell’s Island skyline into its present iconic spectacle, thrusting our city into the modern era. P. 9 Announcing the Roosevelt Island Historical Society 40th Anthony W. Robins is a 20-year veteran of the New York City Anniversary Raffle Landmarks Preservation Commission, and has worked extensively with the Art Deco Society of New York to bring P. 10 Metropolitan Doctor, New York’s modern architectural legacy to the attention of Part 4 city dwellers and visitors alike. In December, as a part of the Roosevelt Island Historical Society’s public lecture series, P. 12 RIHS Calendar; What Are Robins discussed the origins of the Art Deco style and gave Your Treasures Worth? Become an overview of some of New York’s finest Deco buildings. a Member and Support RIHS We encourage you to discover more of our city’s Art Deco period with Robins’ recent book, New York Art Deco: A Guide to Gotham’s Jazz Age Architecture, (SUNY Press, Excelsior Editions, 2017), which features fifteen thoughtful, self-guided walking tours (available at the Roosevelt Island Visitor Center Kiosk). -

BEAUX-ARTS APARTMENTS, 310 East 44Th Street, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission July 11, 1989; Designation List 218 LP-1669 BEAUX-ARTS APARTMENTS, 310 East 44th Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1929-30; Kenneth M. Murchison and Raymond Hood of the firm of Raymond Hood, Godley & Fouilhoux, associated architects. Landmark site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1336, Lot 40. On July 12, 1988, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Beaux Arts Apartments and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 7). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Sixteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Many letters and other expressions of support in favor of designation have been received by the Commission. The owner has expressed certain reservations about the proposed designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS summary Designed by Raymond Hood, among the most prominent American architects of the twentieth century, and built in 1929-30, The Beaux-Arts Apartments is one of the earliest examples in New York City to reflect the trend toward horizontal emphasis in the aesthetic of modern European architecture of the 1920s. Conceived as a corollary to the neighboring Beaux-Arts Institute of Design (a designated New York City Landmark), the Beaux-Arts Apartments at 310 East 44th Street and its twin building on the opposite side of the street were intended to provide residential and studio accommodations for architects and artists, as well as others interested in living in what was anticipated as a midtown artistic community. The Beaux-Arts Development Corporation, a syndicate of architects associated with the Institute and allied professionals, joined forces to finance, build, and manage their own real estate venture. -

The Recommended Reading Lists of Alfred Lawrence Kocher and the Beauty of Utility in 1920S America

2020 volume 17 | issue 1 In Search of a Cultural Background: The Recommended Reading Lists of Alfred Lawrence Kocher and the Beauty of Utility in 1920s America Mario Canato Abstract The modernist architect and critic, Alfred Lawrence Kocher, proposed and commented on many bibliographical ref- erences in the Architectural Record in the years 1924-25. Recent studies on American architecture of the 1920s and 1930s have recognized the peculiar character of modernism in the United States and have gone in search of its cultural and social roots. However, Kocher’s extensive lists have so far been completely overlooked. They were based for the most part on the correspondence he exchanged with a number of American and British architects and George Bernard Shaw: he had sent to them a circular letter, asking for recommendations on texts on background literature that a young architect should know. The unpublished correspondence that Kocher had with Louis Sullivan and the 19 texts on “Aesthetics and Theory of Architecture” are analyzed in particular by the author. Although from 1927 onwards Kocher became a passionate supporter of European rationalist architecture, his bibli- ographies cannot be considered a conscious foundational literature on modernism and modernity. They rather give an idea of the ‘cultural trunk’ on which the discussion on modern European architecture was going to be grafted; they help to illuminate the scene on which American architects moved in the mid-1920s. In some of the texts, the pragmatic notion of utility shines through, as − sometimes connectedly − does the concept of a creative act as a free, ‘natural’ act, which derived from American transcendentalism.