Article Is Available Britain and Ireland to 1960: Part 2: Years AD 1801–1850, Int

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danube River Cruise Flyer-KCTS9-MAURO V2.Indd

AlkiAlki ToursTours DanubeDanube RiverRiver CruiseCruise Join and Mauro & SAVE $800 Connie Golmarvi from Assaggio per couple Ristorante on an Exclusive Cruise aboard the Amadeus Queen October 15-26, 2018 3 Nights Prague & 7 Nights River Cruise from Passau to Budapest • Vienna • Linz • Melk • and More! PRAGUE CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA GERMANY Cruise Route Emmersdorf Passau Bratislava Motorcoach Route Linz Vienna Budapest Extension MUNICH Melk AUSTRIA HUNGARY 206.935.6848 • www.alkitours.com 6417-A Fauntleroy Way SW • Seattle, WA 98136 TOUR DATES: October *15-26, 2018 12 Days LAND ONLY PRICE: As low as $4249 per person/do if you book early! Sail right into the pages of a storybook along the legendary Danube, *Tour dates include a travel day to Prague. Call for special, through pages gilded with history, and past the turrets and towers of castles optional Oct 15th airfare pricing. steeped in legend. You’ll meander along the fabled “Blue Danube” to grand cities like Vienna and Budapest where kings and queens once waltzed, and to gingerbread towns that evoke tales of Hansel and Gretel and the Brothers Grimm. If you listen closely, you might hear the haunting melody of the Lorelei siren herself as you cruise past her infamous river cliff post! PEAK SEASON, Five-Star Escorted During this 12-day journey, encounter the grand cities and quaint villages along European Cruise & Tour the celebrated Danube River. Explore both sides of Hungary’s capital–traditional Vacation Includes: “Buda” and the more cosmopolitan “Pest”–and from Fishermen’s Bastion, see how the river divides this fascinating city. Experience Vienna’s imperial architec- • Welcome dinner ture and gracious culture, and tour riverside towns in Austria’s Wachau Valley. -

Wiener Neustadt in MOTION!

Wiener Neustadt Discover. Experience. Live. CITY IN MOTION! ATTRACTIONS AND TOURS EVERYTHING IS NEW IN WIENER NEUSTADT The birthplace of Emperor Maximilian I, Wiener Neustadt is of great historical significance. The history of Wiener Neustadt, spanning centu- ries, is so exciting that it is quite surprising that the gates to the important sights were not opened much earlier. However, because of this, the Lower Austrian Provincial Exhibition 2019 sparked an CONTENTS initial, veritable rush to visit these, difficult to access, historical locations. Here you will find a complete overview of the Attractions ...........................................Page 4 sights and museums of Wiener Neustadt. Freely accessible highlights ................... Page 15 Culinary delights are not to be neglected either. Museums .............................................Page 18 Wiener Neustadt has an extraordinary variety of bars and restaurants to offer: from the rustic Getting there and parking ...................... Page 28 Stadtheurigen to the Beisl and Gasthaus with Useful contacts ....................................Page 32 everything to home-style cooking to top level cui- Town map .............................................Page 34 sine. Numerous coffee houses line the entire city center, inviting you to linger. 2 3 SIGHTSEEING THERESIAN MILITARY ACADEMY The castle was built about 50 years after the city was founded in 1192 as a military base for the last Babenberger, Friedrich II. Over the centuries the castle has been expanded and been given various new purposes. Emperor Friedrich III. had the castle fundamentally rebuilt, largely giving it its current appearance. Emperor Maximilian I was born and baptized in the castle in Wiener Neustadt and spent his youth here. From here the Holy Roman Empire was expanded. The empire grew so large that “the sun never set“. -

What Are We Doing with (Or To) the F-Scale?

5.6 What Are We Doing with (or to) the F-Scale? Daniel McCarthy, Joseph Schaefer and Roger Edwards NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center Norman, OK 1. Introduction Dr. T. Theodore Fujita developed the F- Scale, or Fujita Scale, in 1971 to provide a way to compare mesoscale windstorms by estimating the wind speed in hurricanes or tornadoes through an evaluation of the observed damage (Fujita 1971). Fujita grouped wind damage into six categories of increasing devastation (F0 through F5). Then for each damage class, he estimated the wind speed range capable of causing the damage. When deriving the scale, Fujita cunningly bridged the speeds between the Beaufort Scale (Huler 2005) used to estimate wind speeds through hurricane intensity and the Mach scale for near sonic speed winds. Fujita developed the following equation to estimate the wind speed associated with the damage produced by a tornado: Figure 1: Fujita's plot of how the F-Scale V = 14.1(F+2)3/2 connects with the Beaufort Scale and Mach number. From Fujita’s SMRP No. 91, 1971. where V is the speed in miles per hour, and F is the F-category of the damage. This Amazingly, the University of Oklahoma equation led to the graph devised by Fujita Doppler-On-Wheels measured up to 318 in Figure 1. mph flow some tens of meters above the ground in this tornado (Burgess et. al, 2002). Fujita and his staff used this scale to map out and analyze 148 tornadoes in the Super 2. Early Applications Tornado Outbreak of 3-4 April 1974. -

Schienenkorridore Für Die Steiermark Ausbauvorstellungen Für Den Güter- Und Personenverkehr

Steirische Regionalpolitische Studien Nr. 01/2018 Schienenkorridore für die Steiermark Ausbauvorstellungen für den Güter- und Personenverkehr Autoren: DI Dr.Helmut Adelsberger Dkfm. Dr. Heinz Petzmann Studie im Auftrag der steirischen Sozialpartner, März 2018 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Executive Summary 3 1. Das Transeuropäische Verkehrsnetz; Relevanz für die Steiermark 7 2. Raumstruktur und Lage der Steiermark im österreichischen und europäischen Schienennetz 14 2.1. Die Raumstruktur der Steiermark 14 2.2. Die Lage der Steiermark im österreichischen und europäischen Schienennetz 16 3. Bestehende Situation und Ziele 24 4. Der Baltisch-Adriatische Korridor 29 4.1. Bestand und aktuelle Planungen von der Ostsee bis einschließlich Wien 29 4.2. Bestand und aktuelle Planungen südlich von Wien bis Bruck an der Mur 31 4.3. Bestand und aktuelle Planungen südwestlich von Graz 36 4.4. Verkehrsströme im Baltisch-Adriatischen Korridor 39 4.5. Ausbaubedarf im Baltisch-Adriatischen Korridor 41 5. Die Pyhrnachse 45 5.1. Die angestrebte Verankerung der Pyhrnachse im TEN-T 45 5.2. Bestand und aktuelle Planungen nördlich von Bruck an der Mur 47 5.3. Bestand und aktuelle Planungen südlich von Werndorf 52 5.4. Verkehrsströme in der Pyhrnachse 56 5.5. Ausbaubedarf in der Pyhrnachse 59 5.6. Die Krapina-Bahn 62 6. Der Abschnitt Bruck an der Mur – Graz – Werndorf 68 6.1. Bestand und aktuelle Planungen 68 6.2. Verkehrsströme im Abschnitt Bruck an der Mur – Graz – Werndorf 73 6.3. Ausbaubedarf im Abschnitt Bruck an der Mur – Graz – Werndorf 74 7. Die Grazer Ostbahn 84 7.1. Bestand und aktuelle Planungen 84 7.2. Ausbaubedarf der Grazer Ostbahn 86 8. -

19.4 Updated Mobile Radar Climatology of Supercell

19.4 UPDATED MOBILE RADAR CLIMATOLOGY OF SUPERCELL TORNADO STRUCTURES AND DYNAMICS Curtis R. Alexander* and Joshua M. Wurman Center for Severe Weather Research, Boulder, Colorado 1. INTRODUCTION evolution of angular momentum and vorticity near the surface in many of the tornado cases is also High-resolution mobile radar observations of providing some insight into possible modes of supercell tornadoes have been collected by the scale contraction for tornadogenesis and failure. Doppler On Wheels (DOWs) platform between 1995 and present. The result of this ongoing effort 2. DATA is a large observational database spanning over 150 separate supercell tornadoes with a typical The DOWs have collected observations in and data resolution of O(50 m X 50 m X 50 m), near supercell tornadoes from 1995 through 2008 updates every O(60 s) and measurements within including the fields of Doppler velocity, received 20 m of the surface (Wurman et al. 1997; Wurman power, normalized coherent power, radar 1999, 2001). reflectivity, coherent reflectivity and spectral width (Wurman et al. 1997). Stemming from this database is a multi-tiered effort to characterize the structure and dynamics of A typical observation is a four-second quasi- the high wind speed environments in and near horizontal scan through a tornado vortex. To date supercell tornadoes. To this end, a suite of there have been over 10000 DOW observations of algorithms is applied to the radar tornado supercell tornadoes comprising over 150 individual observations for quality assurance along with tornadoes. detection, tracking and extraction of kinematic attributes. Data used for this study include DOW supercell tornado observations from 1995-2003 comprising The integration of observations across tornado about 5000 individual observations of 69 different cases in the database is providing an estimate of mesocyclone-associated tornadoes. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Building the Medieval World Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BUILDING THE MEDIEVAL WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Christine Sciacca | 96 pages | 31 Mar 2010 | Getty Trust Publications | 9781606060063 | English | Los Angeles, United States Building the Medieval World PDF Book Medieval Inn and Tavern by Dimitris Romeo Havlidis Jan 25, Sociology At some point in every medieval fantasy movie or game, the heroes end up to an inn or tavern to rest their bones, fill their bellies with ale, and gorge on ridiculous amounts of food. A craftsman perched on a ladder wields a small trowel for applying mortar, while his partner to the right holds a pick. Architecture is a frequent setting for biblical stories, and in some cases buildings themselves play key roles in the narratives. Paul Getty Museum and the British Library. A dark secret spans several Illuminated manuscripts often served as historical documents of medieval architecture. Being involved in the construction of a cathedral, even as the building patron, required a willingness to be part of a process that was larger than oneself. Medieval Church Architecture. The farming year in medieval times, the tasks that the serfs had to undertake and the tools they had to use for farming. You will work alongside CS, Archi, Social Science, and Humanity students to research and design a truly great product. This Site. Published March 30th by J. Each team created excel spreadsheets of these features and kept files of images of particular elements taken from their research. Find out what drove people to build such monumental buildings, and how they did it. Leave a Reply Cancel reply Your email address will not be published. -

Stellungskundmachung 2020 NÖ

M I L I T Ä R K O M M A N D O N I E D E R Ö S T E R R E I C H Ergänzungsabteilung: 3101 St. PÖLTEN, Kommandogebäude Feldmarschall Hess, Schießstattring 8 Parteienverkehr: Mo-Do von 0800 bis 1400 Uhr und Fr von 0800 bis 1200 Uhr Telefon: 050201/30, Fax: 050201/30-17410 E-Mail: [email protected] STELLUNGSKUNDMACHUNG 2020 Auf Grund des § 18 Abs. 1 des Wehrgesetzes 2001 (WG 2001), BGBl. I Nr. 146, haben sich alle österreichischen Staatsbürger männlichen Geschlechtes des G E B U R T S J A H R G A N G E S 2 0 0 2 sowie alle älteren wehrpflichtigen Jahrgänge, die bisher der Stellungspflicht noch nicht nachgekommen sind, gemäß dem unten angeführten Plan der Stellung zu unterziehen. Österreichische Staatsbürger des Geburtsjahrganges 2002 oder eines älteren Geburtsjahrganges, bei denen die Stellungspflicht erst nach dem in dieser Stellungskundma- chung festgelegten Stellungstag entsteht, haben am 16.12.2020 zur Stellung zu erscheinen, sofern sie nicht vorher vom Militärkommando persönlich geladen wurden. Für Stellungspflichtige, welche ihren Hauptwohnsitz nicht in Österreich haben, gilt diese Stellungskundmachung nicht. Sie werden gegebenenfalls gesondert zur Stellung auf- gefordert. Für die Stellung ist insbesondere Folgendes zu beachten: 1. Für den Bereich des Militärkommandos NIEDERÖSTERREICH werden die Stellungspflichtigen durch die 3. Bei Vorliegen besonders schwerwiegender Gründe besteht die Möglichkeit, dass Stellungspflichtige auf ihren An- Stellungskommission NIEDERÖSTERREICH der Stellung unterzogen. Das Stellungsverfahren nimmt in der Regel trag in einem anderen Bundesland oder zu einem anderen Termin der Stellung unterzogen werden. 1 1/2 Tage in Anspruch. -

Baroque Architecture in the Former Habsburg Residences of Graz and Innsbruck

EMBODIMENTS OF POWER? Baroque Architecture in the Former Habsburg Residences of Graz and Innsbruck Mark Hengerer Introduction Having overcome the political, religious, and economic crisis of the Thirty Years' War, princes in central Europe started to reconstruct their palaces and build towns as monuments of power. Baroque residences such as Karlsruhe combine the princely palace with the city, and even the territory, and were considered para digms of rule in the age of absolutism.' In Austrian Vienna, both the nobility and the imperial family undertook reshaping the city as a baroque residence only after the second Ottoman siege in 1683. Despite the Reichsstif of Emperor Karl VI, the baroque parts of the Viennese Hofburg and the baroque summer residence of Sch6nbrunn were executed as the style itself was on the wane, and were still incomplete in the Enlightenment period.2 It may be stated, then, that the com plex symbolic setting of baroque Viennese architecture reveals the complex power relations between the House of Habsburg and the nobility, who together formed a SOft of "diarchy," so that the Habsburgs did not exercise absolutist rule. 3 Ad ditionally, it cannot be overlooked that the lower nobility and burghers, though hardly politically influential, imitated the new style, which was of course by no means protected by any sort of copyright.4 For all these reasons, reading baroque cities as embodiments of powers is prob lematic. Such a project is faced with a phenomenon situated between complex actual power relations and a more or less learned discourse on princely power and 10 architecture (which was part of the art realm as well), and princes, noblemen, and citizens inspired to build in the baroque style. -

Fahrplan 2021 Fahrplanvorschau Bahn Und Bus Verbesserungen

Fahrplan 2021 Fahrplanvorschau Bahn und Bus Verbesserungen Stand November 2020 Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr! Inhalt 1. Wesentliche Neuerungen im Angebot 2. Änderungen im Detail 1. Westachse und Franz-Josefs-Bahn 2. Südachse 3. Ostachse und Nordburgenland 4. S-Bahn Wien und Nordäste 4 Wesentliche Neuerungen im Angebot Fahrplan 2021 gültig ab 13. Dezember 2020 Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr! Änderungen Fahrplan 2021: Überblick Laaer Ostbahn weitere Taktlückenschlüsse und täglicher Stundentakt Angebotsausweitungen im gesamten Netz • zusätzliche Abend-/Frühzüge auf diversen Strecken bis Laa/Thaya 4 Züge pro Stunde bis • zusätzliche HVZ-Verstärker u.a. auf Regionalbahnen St. Andrä-Wördern Weiterführung der S40-Verstärker Wien FJBf. – Kritzendorf als R40 bis St. Andrä-Wördern Nordbahn Stundentakt Mo – Fr bis Bernhardsthal bzw. Břeclav Tullnerfeldbahn: S40-Stundentakt auch am Wochenende St. Pölten – Traismauer – Tullnerfeld (weiter nach Wien FJBf.) Elektrifizierung Marchfeldbahn: Gänserndorf – Marchegg Weiterführung der S1 aus Wien von Gänserndorf nach Marchegg, täglicher Abendzüge auf der Rudolfsbahn Stundentakt Ausweitung des Stundentakts Amstetten – Waidhofen/Ybbs bis ~0:05 ab Amstetten Badner Bahn Wien Oper – Wiener Neudorf durchgehender 7,5-Minuten-Takt Neusiedler Seebahn Citybahn Waidhofen: Wien – Neusiedl/See - Pamhagen • Halbstundentakt (statt Stundentakt) • täglicher und durchgängiger • neuer Endpunkt Waidhofen Stundentakt Pestalozzistraße (Streckenkürzung) • Betriebszeitausweitung Innere Aspangbahn: Wien Hbf. – Traiskirchen – Wiener Neustadt -

Efpia Report

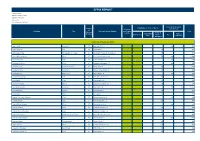

EFPIA REPORT Country: Austria Reporting Currency: EUR Reporting Year: 2016 Version: 03 Date Published: 17/07/2017 Fees for Service and Country Contribution to Costs of Events Donations Consultancy of Full Name City Principal Practice Address and Grants Total Principal Travel & to HCOs Registration Related Practice Sponsorship Accom- Fees Fees Expenses modation Health Care Professionals (HCPs) Agnes Loidl Innsbruck AT Innrain 43/Parterre 500 180 680 Agnes Silgoner Linz AT Seilerstätte 4 193 193 Agnieszka Ziomka Schwarzach im Pongau AT Kardinal Schwarzenberg-Straße 2-6 193 193 Ahmet Gökhan Uyanik Wien AT Heinrich Collin-Straße 30 758 800 1.558 Akós Heinemann Graz AT Heinrichstraße 31a 600 600 Alexander Fortelny Wien AT Eingang Löblichgasse 16 400 400 Alexander Gallee Vorderweißenbach AT Sonnenplatz 2 377 377 Alexander Stifter Hollabrunn AT Robert Löffler-Straße 20 193 193 Alexandra Pöll Hall in Tirol AT Milser Straße 10 400 400 Alexandra Weidinger Linz AT Karl Wiser-Straße 7/1 106 106 Alice Kafka Wien AT Auhofstraße 189 155 155 Ali Kaan Akmanlar Hallein AT Bürgermeisterstraße 34 174 174 Alois Günther Gastl Innsbruck AT Anichstraße 35 500 522 1.022 Alois Waschnig Leoben AT Schillerstraße 3 193 193 Amila Siljak Hallein AT Griesplatz 8 751 751 Andrea-Eva Bartok-Heinrich Wien AT Wienerbergstraße 13 300 300 Andrea Handke Graz AT Auenbruggerplatz 15 544 544 Andrea Mohn-Staudner Wien AT Sanatoriumstraße 2 500 500 Andrea Schadler Graz AT Elisabethinergasse 14 135 135 Andrea Scherr-Umundum Graz AT Elisabethinergasse 14 135 135 Andreas Kretschmer -

The Enhanced Fujita Tornado Scale

NCDC: Educational Topics: Enhanced Fujita Scale Page 1 of 3 DOC NOAA NESDIS NCDC > > > Search Field: Search NCDC Education / EF Tornado Scale / Tornado Climatology / Search NCDC The Enhanced Fujita Tornado Scale Wind speeds in tornadoes range from values below that of weak hurricane speeds to more than 300 miles per hour! Unlike hurricanes, which produce wind speeds of generally lesser values over relatively widespread areas (when compared to tornadoes), the maximum winds in tornadoes are often confined to extremely small areas and can vary tremendously over very short distances, even within the funnel itself. The tales of complete destruction of one house next to one that is totally undamaged are true and well-documented. The Original Fujita Tornado Scale In 1971, Dr. T. Theodore Fujita of the University of Chicago devised a six-category scale to classify U.S. tornadoes into six damage categories, called F0-F5. F0 describes the weakest tornadoes and F5 describes only the most destructive tornadoes. The Fujita tornado scale (or the "F-scale") has subsequently become the definitive scale for estimating wind speeds within tornadoes based upon the damage caused by the tornado. It is used extensively by the National Weather Service in investigating tornadoes, by scientists studying the behavior and climatology of tornadoes, and by engineers correlating damage to different types of structures with different estimated tornado wind speeds. The original Fujita scale bridges the gap between the Beaufort Wind Speed Scale and Mach numbers (ratio of the speed of an object to the speed of sound) by connecting Beaufort Force 12 with Mach 1 in twelve steps.