Financing Housing Improvements in Slum Communities in Ghana: the Case of the Kumasi Metropolis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability of the Urban Transport System of Kumasi

SUSTAINABILITY OF THE URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF KUMASI By DENNIS KWADWO OKYERE (B.Sc. HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PLANNING) A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (MPHIL) PLANNING Department of Planning College of Architecture and Planning October, 2012 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the M.Phil (Planning) and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person or material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. DENNIS KWADWO OKYERE ………………………… …………………….. (PG 5433611) SIGNATURE DATE CERTIFIED BY: PROF. KWASI KWAFO ADARKWA ……………………….. ……………………. (SUPERVISOR) SIGNATURE DATE CERTIFIED BY: DR. DANIEL K.B. INKOOM ………………………... ……………………. (HEAD OF DEPARTMENT) SIGNATURE DATE ii ABSTRACT Sustainable transportation is of great importance in today’s world, because of concerns regarding the environmental, economic, and social equity impacts of transportation systems. Sustainable development can be defined as the development that meets the needs of the present, without compromising on the future ability to meet the same needs. Sustainable transportation can be considered as an expression of sustainable development in the transport sector. This is because of the high growth of the transport sector’s energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions at the global scale, its impact on the economy, as well as, on social well-being. Since the mid-20th century, the negative side effects of urban transportation have become particularly apparent in the metropolitan areas of developed countries. -

WAHABU ADAM.Pdf

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Kumasi, Ghana College of Engineering Department of Civil Engineering CHARACTERIZATION OF DIVERTED SOLID WASTE IN KUMASI ADAM WAHABU MSc. Thesis August 2012 Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Adam Wahabu MSc. Thesis, 2012 CHARACTERIZATION OF DIVERTED SOLID WASTE IN KUMASI By ADAM WAHABU A Thesis Submitted to the Department Of Civil Engineering Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of MASTER OF SCIENCE In Water supply and environmental sanitation August 2012 Characterization of diverted solid waste Page ii Adam Wahabu MSc. Thesis, 2012 Certification I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the MSc. and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person or material which has been accepted for the award of any degree of the university, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. ADAM WAHABU ………………… ………………… (PG 4777110) Signature Date Certified by: Dr. S.OduroKwarteng …………………. ……….............. (Principal supervisor) Signature Date Prof. Mrs. EsiAwuah …………………... ………………... (Second supervisor) Signature Date Mr. P. Kotoka …………………… …………………. (Third supervisor) Signature Date Prof. M. Salifu ……………….. ………………… (Head of dept., civil engineering) Signature Date Characterization of diverted solid waste Page ii Adam Wahabu MSc. Thesis, 2012 Dedication THIS THESIS IS DEDICATED TO MY LATE FATHER, MR. MAHAMUD ADAM Characterization of diverted solid waste Page iii Adam Wahabu MSc. Thesis, 2012 Abstract The current practice of Solid Waste Management (SWM) in Ghana is that of disposal model. It is increasingly difficult to site new landfills within big cities due to scarce space and public outcry. -

Ethnic Markets in the American Retail Landscape: African

ETHNIC MARKETS IN THE AMERICAN RETAIL LANDSCAPE: AFRICAN MARKETS IN COLUMBUS, CLEVELAND, CINCINNATI, AND AKRON, OHIO A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Hyiamang Safo Odoom December 2012 Dissertation written by Hyiamang Safo Odoom B.A., University of Ghana,Ghana, 1980 M.S., University of Cape Coast, Ghana, 1991 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2012 Approved by ___________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee David H. Kaplan, Ph.D. ___________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Milton E. Harvey, Ph.D. ___________________________, Sarah Smiley, Ph.D. ___________________________, Steven Brown, Ph.D. ___________________________, Polycarp Ikuenobe, Ph.D. Accepted by ___________________________, Chair, Department of Geography Mandy Munro-Stasiuk, Ph.D. ___________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Timothy S. Moerland, Ph.D. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................... viii LIST OF TABLES ...............................................................................................................x ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................ xi CHAPTER ONE: THE AFRICAN MARKET/GROCERY STORE .................................1 Introduction…………………….……………………………….………………….1 What is a Market/African Market? ..........................................................................1 -

Eindhoven University of Technology MASTER Public Transport in Ghana

Eindhoven University of Technology MASTER Public transport in Ghana : assessment of opportunities to improve the capacity of the Kejetia public transport terminal in Kumasi, Ghana van Hoeven, Nathalie Award date: 1999 Link to publication Disclaimer This document contains a student thesis (bachelor's or master's), as authored by a student at Eindhoven University of Technology. Student theses are made available in the TU/e repository upon obtaining the required degree. The grade received is not published on the document as presented in the repository. The required complexity or quality of research of student theses may vary by program, and the required minimum study period may vary in duration. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ASSESSMENT OF OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE THE CAPACITY OF THE KEJETIA PUBLIC TRANSPORT TERMINAL IN KUMASI, GHANA I APPENDICES N. van Hoeven December 1999 Supervisors Eindhoven University of Technology Drs. H. C.J.J. Gaiflard Ir. E.L.C. van Egmond-de Wilde de Ligny Faculty of Technology Management Department of International Technology and Development Studies Ir. A. W.J. Borgers Faculty of Building Engineering Department of Planning In co-operation with Dr. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Trust and power in a farmer-trader relations : a study of small scale vegetable production and marketing systems in Ghana. Lyon, Fergus How to cite: Lyon, Fergus (2000) Trust and power in a farmer-trader relations : a study of small scale vegetable production and marketing systems in Ghana., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1474/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Trust and power in farmer-trader relations: A study of small scale vegetable production and marketing systems in Ghana Ph.D. Thesis Fergus Lyon A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the Department of Geography, University of Durham, UK 2000 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived front it should be acknowledged. -

Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE COMPOSITE BUDGET Of the KUMASI METROPOLITAN ASSEMBLY for the 2014 FISCAL YEAR Table of Contents SECTION 1: COMPOSITE BUDGET 2014 - NARRATIVE STATEMENT……4 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………………...4 Goal, Mission and Vision……………………………………………………..…………………………….4 BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………………………………........4 Location……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 DEMOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Sex Structure………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 Population Density…………………………………………………………..…………………….………….5 Household Sizes/Characteristics…………………………………………………………….………….5 Rural Urban Split……………………………………………………………………………………………….5 THE LOCAL ECONOMY……………………………………………………………………………………...5 Service Sector…………………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Industrial Sector……………………………………………………………………………………….……….6 Agricultural Sector……………………………………………………………………………….……………6 Economic Infrastructure……………………………………………………………………………………7 Marketing Facilities……………………………………………………………….………………………...7 Energy……………………………………………………………………….……………………….………….…7 Telecommunication Services……………………………………….……………………………………7 Transportation…………………………………….……………………………………………………………7 Tourism………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…8 Hospitality Industry………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Health Care…………………………………………………………………………………………………….…8 Education………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Health……………………………………………………….……………………………………………………..9 Structure Of The Assembly…………………….……………………,………………………………….10 Assumptions Underlining The Budget Formulation………………………………………….24 -

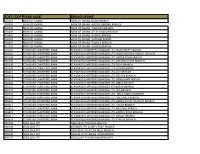

ASHANTI REGION.Pdf

ASHANTI REGION NAME TELEPHONE NUMBER LOCATION CERTIFICATION CLASS 1 ABDULAI BASHIRU BEN KUMASI DOMESTIC 2 ABDULAI MOHAMMED KUMASI DOMESTIC 3 ABOAGYE DANIEL AKWASI 0244756870 KUMASI COMMERCIAL 4 ABOAGYE ELVIS 0242978816/0233978816 KUMASI DOMESTIC 5 ABOAGYE KWAME 0207163334 KUMASI DOMESTIC 6 ABREFAH NOAH KUMASI DOMESTIC 7 ABROKWA, SAMUEL KORANTENG 0246590209 ADUM , KUMASI COMMERCIAL 8 ABUBEKR COLLINS 0508895569 NEW NYAMEREREYERE COMMERCIAL 9 ACCOMFORD RICHARD 0244926482 KENTINKRONO COMMERCIAL 10 ACHEAMPONG AKWASI 0208063734 AMAKOM-STADIUM COMMERCIAL 11 ACHEAMPONG JOE ELLIS 0244560405 ADUM, KUMASI INDUSTRIAL 12 ACHEAMPONG KWABENA 0243375366 NEW SUAME KUMASI DOMESTIC 13 ACHEAMPONG STEPHEN 0247937033 OBUASI NEW ESTATE DOMESTIC 14 ACHEAMPONG WILLIAM 0203321176 KUMASI COMMERCIAL 15 ACHEAMPONG WILLIAM 0249691088 MAKRO, ABUAKWA COMMERCIAL 16 ACQUAH CLEMENT 0243505887 BOHYEN, KUMASI COMMERCIAL 17 ACQUAH SAMUEL 0208124324 KUMASI DOMESTIC 18 ADADE NELSON KWAME 0272932398 ASOKORE-MAMPONG INDUSTRIAL 19 ADAMS ABDELAH KUMASI DOMESTIC 20 ADAMS BERNARD 0207612895 ATONSU SAWUA-AWIEM COMMERCIAL 21 ADAMS JAMES KOFI 0244616357 KUMASI DOMESTIC 22 ADARKWAH SAMUEL 0543586905 OBUASI NEW ESTATE DOMESTIC 23 ADDAI EMMANUEL KWAKU 0244010115 KUMASI COMMERCIAL 24 ADDAI ERNEST 0245488725 KUMASI COMMERCIAL 25 ADDAI FRANCIS 0249319198 EJISU, KUMASI DOMESTIC 26 ADDAI JAMES 0275695379 NKAMPROM OBUASI DOMESTIC 27 ADDAI KINGSLEY 0277411263 OBUASI BIDIESO DOMESTIC 28 ADDO OFORI BESTLUCK 0244615427 KOTEI DAAKYESO DOMESTIC 29 ADDO SAMUEL ARCHIBALD- MENSAH 0264181302 ADUM METHODIST, -

Sort Code Bank Name Branch Name

SORT CODE BANK NAME BRANCH NAME 010101 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA ACCRA BRANCH 010303 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -AGONA SWEDRU BRANCH 010401 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -TAKORADI BRANCH 010402 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -SEFWI BOAKO BRANCH 010601 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -KUMASI BRANCH 010701 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -SUNYANI BRANCH 010801 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA -TAMALE BRANCH 011101 BANK OF GHANA BANK OF GHANA - HOHOE BRANCH 020101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-HIGH STREET BRANCH 020102 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD- INDEPENDENCE AVENUE BRANCH 020104 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-LIBERIA ROAD BRANCH 020105 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-OPEIBEA HOUSE BRANCH 020106 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-TEMA BRANCH 020108 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-LEGON BRANCH 020112 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-OSU BRANCH 020118 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-SPINTEX BRANCH 020121 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-DANSOMAN BRANCH 020126 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD-ABEKA BRANCH 020127 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH)-ACHIMOTA BRANCH 020129 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD- NIA BRANCH 020132 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD- TEMA HABOUR BRANCH 020133 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK STANDARD CHARTERED BANK(GH) LTD- WESTHILLS BRANCH 020436 -

Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly

KUMASI METROPOLITAN ASSEMBLY IMPOSITION OF RATES AND FEE FIXING RESOLUTION, 2018 PURSUANT TO LOCAL GOVERNANCE ACT 2016 (ACT 936) RESOLVED THAT BY VIRTUE OF PART V AMONG OTHERS OF THE LOCAL GOVERNANCE ACT 2016, (ACT 936) AND THE "GUIDELINES FOR CHARGING OF FEES FOR THE PROVISION OF SERVICES AND FACILITIES AND GRANTING OF LICENCES AND PERMITS BY METROPOLITAN/MUNICIPAL/DISTRICT ASSEMBLIES", THE FOLLOWING FEES BE CHARGED AND LEVIED BY THE KUMASI METROPOLITAN ASSEMBLY FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 1ST JANUARY, 2018 TO 31ST DECEMBER, 2018 GENERAL IMPOSITION OF RATES, 2018 CATEGORY OF PREMISES AND RATE AREA 2018 1st Class 0.001 New Amakom Ext., Asokwa, Ayigya Ext. Bomso Residential area, Atwima-Amanfrom, Adiebeba, Adiembra Ahinsan Estate Ext., Odeneho Kwadaso, O.T.B. North/South Patasi, Sokoban O.T.A., Mbrom (As designated by the approved land-use plan) *A minimum annual rate of GHc120 ( i.e 10 GHc per month) to apply where the property rate is below GHc120 p/a 2nd Class Res. 0.00098 Dichemso, Manhyia/Manhyia Ext., Odumase/Odumase Ext., Krobo Odumase, Oduro, Zongo Ext., North Zongo, South Zongo, Yenyawoso, Atimpongya, North Kwadaso, Kwadaso-South East Fankyinebra, Kwadaso Estate, Kwadaso Estate Ext., New Suame, Suntreso Ext., Buokrom Estate, Kentikrono, Benimase, Odoum, Ayeduase, Anwomaso, Bebre, Tafo Nhyiaeso, Old Tafo, Adoato, Anoo/Adumanu, Amakom-Abrotia, New Tafo, Ampabame, Pankrono Old Amakom, Asafo, Dadiesoaba, Bimpeh Hill, Bompata, Nsenie Adompom, North/South Suntreso, Bantama, Santasi, Edwinase New Amakom, Amakom-Bramponso, Ohwimase, , Tarkwa- Maakro Oforikrom, Gyinyase, Atonsu, Agogo, Asuoyeboah, Kyirapatre, Abrepo, Bohyen, Breman, Bosomuru-Nkontwima, Ahinsan, Kropo (As designated by the approved land-use plan) *A minimum annual rate of GHc84 ( i.e GHc7 per month) to apply where the property rate is below GHc84 p/a 3rd Class Res. -

MCE's Sessional Address 2017

KUMASI METROPOLITAN ASSEMBLY (K.M.A.) Sessional ADDRESS DELIVERED BY THE METROPOLITAN CHIEF EXECUTIVE, HONOURABLE OSEI ASSIBEY ANTWI AT THE SECOND ORDINARY MEETING OF THE SECOND SESSION OF THE SEVENTH KUMASI METROPOLITAN ASSEMBLY (KMA) DATE 11TH - 12TH MAY, 2017. @ THE TRUE VINE HOTEL, ADIEBEBA - KUMASI SESSIONAL ADDRESS DELIVERED BY THE MCE, HON. OSEI ASSIBEY ANTWI HONOURABLE PRESIDING MEMBER, HONOURABLE MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT, HONOURABLE ASSEMBLY MEMBERS, NANANOM, HEADS OF DEPARTMENT, THE MEDIA, DISTINGUISHED INVITED GUESTS, LADIES AND GENTLEMEN; I feel truly honoured and humbled, to stand before this august House to present my first Sessional Address as the Chief Executive (MCE) of the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly. First and foremost, I would like to thank the Almighty God for his grace and for making it possible for us to share this memorable day. I would also like to use the opportunity to express my heartfelt THE 2ND ORDINARY MEETING OF THE 2ND SESSION OF THE 7TH KUMASI METROPOLITAN ASSEMBLY 1 SESSIONAL ADDRESS DELIVERED BY THE MCE, HON. OSEI ASSIBEY ANTWI gratitude to His Excellency, the President of the Republic of Ghana, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, for nominating and subsequently appointing me to the high office of the Chief Executive of the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly. My sincerest appreciation further goes to the Asantehene, Otumfuo Osei Tutu II, Nananom, the Ashanti Regional Minister, Hon. Simon Osei-Mensah, the Executives of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), and all those who contributed in diverse ways to make my confirmation a success. I cannot leave out the Honourable Assembly members of KMA. Honourables, I am most grateful for the overwhelming confidence reposed in me during my confirmation. -

EVELYN AMOAH.Pdf

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES SCHOOL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH ENROLLMENT IN NHIS AND ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE: A CASE STUDY OF MIGRANT FEMALE HEADPORTERS AT THE CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OF KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION, GHANA EVELYN AMOAH APRIL, 2014 i KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES SCHOOL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH ENROLLMENT IN NHIS AND ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE: A CASE STUDY OF MIGRANT FEMALE HEADPORTERS AT THE CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OF KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION, GHANA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE AWARD OF DEGREE OF MASTERS IN PUBLIC HEALTH IN HEALTH SERVICES PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT EVELYN AMOAH MASTERS IN PUBLIC HEALTH (HEALTH SERVICES PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT) APRIL 2014 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this script is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person, nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the university, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. ………………………… EVELYN AMOAH (STUDENT) Signature …………………….. DR. AGATHA AKUA BONNEY (ACADEMIC SUPERVISOR) Signature………………… DR.ANTHONY K. ADUSEI (HEAD OF DEPARTMENT) ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my dear daughter Nana Abena Serwaa Dwomoh. iii ACKNOWLEGEMENT I wish to thank several individuals for their contributions to the research work. I would like to thank my able supervisor Dr. (Mrs.) Agatha Bonney for not only guiding me through this process with her keen insights and advice, but has also taught me many valuable lessons along the way. -

Impacts of Urban Land Use Change on Sources of Drinking Water in Kumasi, Ghana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 IMPACTS OF URBAN LAND USE CHANGE ON SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER IN KUMASI, GHANA Michael Kofi dufulE The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Eduful, Michael Kofi, "IMPACTS OF URBAN LAND USE CHANGE ON SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER IN KUMASI, GHANA" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4219. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4219 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMPACTS OF URBAN LAND USE CHANGE ON SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER IN KUMASI, GHANA By MICHAEL KOFI EDUFUL Master of Science in Urban Governance for Development, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom, 2005 Bachelor of Arts in Geography and Sociology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, 2001 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geography, Community and Environmental Planning The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2014 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. David Shively, Chair Department of Geography Dr. Thomas Sullivan Department of Geography Dr. Michelle Bryan Mudd School of Law i ABSTRACT Eduful, Michael, M.S., Spring 2014 Geography Impacts of Urban Land Use Change on Sources of Drinking Water in Kumasi, Ghana Committee Chair: Dr.