Capitalizing on Opportunistic Citizen Science Data to Monitor Urban Biodiversity: a Multi-Taxa Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Apr

Contents APR. 03, 2020 (click on page numbers for links) CONTACT US REGULATORY UPDATE subscribers@chemwatch. ASIA PACIFIC net Japan GHS classifications updated .............................................................................4 tel +61 3 9572 4700 South Korea revises Toxic Chemical Substances List ............................................4 fax +61 3 9572 4777 India increases priority substance list to 750 chemicals .....................................5 1227 Glen Huntly Rd AMERICA Glen Huntly Pentagon Reports 250 New Sites Are Contaminated with PFAS ......................7 Victoria 3163 Australia Requirement to Report Accidental Releases to Chemical Safety Board Takes Effect .............................................................................................................8 Canadian Center for Occupational Health and Safety Posts Podcast on Hazards of Nanomaterials and How to Control Exposure ..........................11 EUROPE NGOs urge tougher FCM controls in EU Farm to Fork strategy ......................11 EU Commission to ban three more allergenic fragrances in toys ..................13 The ADCR Consortium has extended its membership window .....................14 * While Chemwatch has taken all efforts to REACH UPDATE ensure the accuracy CLH targeted consultation launched on Daminozide .......................................15 of information in 22 REACH Testing proposal consultations launched ..........................................15 this publication, it ECHA to support EU-wide action against COVID-19 -

Citizen Science Apps and Sites Updated 3/29/19 Sdh

Citizen Science Apps and Sites Updated 3/29/19 sdh eBird www.ebird.org A real-time, online checklist program, eBird has revolutionized the way that the birding com- munity reports and accesses information about birds. The observations of each participant join those of others in an international network of eBird users and is with a global communi- ty of educators, land managers, ornithologists, and conservation biologists. Project Feederwatch www.feederwatch.org Project FeederWatch is a winter-long survey of birds that visit feeders at backyards, nature centers, community areas, and other locales in North America. FeederWatchers periodically count the birds they see at their feeders from November through early April and send their counts to Project FeederWatch. NestWatch www.nestwatch.org NestWatch is a nationwide monitoring program designed to track status and trends in the re- productive biology of birds, including when nesting occurs, number of eggs laid, how many eggs hatch, and how many hatchlings survive. Follow the directions on the website to become a certified NestWatcher, find a bird nest, visit the nest every 3-4 days to record what you see, and then report this information on the site. iNaturalist www.inaturalist.org Every observation can contribute to biodiversity science, from the rarest butterfly to the most common backyard weed. We share your findings with scientific data repositories like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility to help scientists find and use your data. All you have to do is observe. Hummingbirds at Home http://www.hummingbirdsathome.org/ Audubon’s Hummingbirds at Home program was designed to mobilize citizen scientists across the U.S. -

February 2021

Gloucester County Nature Club Monthly Newsletter www.gcnatureclub.org Nature Club meetings are open to the public. February 2021 Monthly GCNC meetings are currently suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Please stay tuned, as the situation is continually evolving. Our regular monthly meetings are may be suspended, but we are happy to be able to present the following: Special Live Online Program! Cultivating Respect for Insects - An overview of the ecosystem services that insects provide. Thursday, February 11, 2021 at 7:00pm Presenter: Dr. Daniel Duran, Assistant Professor, Rowan U; Naturalist, Scotland Run Park Program Coordinator: Rich Dilks 856-468-6342 Web link: https://meet.jit.si/GCNCMeeting Simply put: all life on earth depends on insects, for more reasons than most people realize. This talk will explore some of the immeasurably important ways that insects keep ecosystems functioning. Nutrient recycling, pollination services, and trophic interactions will be reviewed. Lastly, there will be a discussion of the ways in which we can conserve our much needed insect diversity. “My interests are in the fields of systematics, taxonomy, and conservation. My research is primarily focused on biodiversity exploration and the discovery of 'cryptic species'; species that are distinct evolutionary units, but go undetected due to physical similarity with closely related species. I mostly use tiger beetles (Cicindelinae) as a study system. I am also interested in examining the important roles of insect and plant biodiversity in ecosystem functioning.” - Dr. Daniel Duran 1 Dr. Duran has taught a wide range of ecology and evolution courses at the university level, and he gives public lectures about the importance of biodiversity. -

Introducing Inaturalist

Introducing iNaturalist: Supplemental Instructional Resources for Learning to Use the iNaturalist Observation Collection System NCBG Independent Study Project Suzanne Cadwell September 2013 Project summary iNaturalist, is a free, web-and mobile-app-based system that has been used by dozens of citizen science projects to collect, organize, and verify species observation data. The goal of this project was to develop instructional materials to supplement those available on the iNaturalist.org website. All resources developed for the project, including written, pictorial, and video resources are available at http://inaturalist.web.unc.edu. After these resources were published, the existing help pages on iNaturalist.org were expanded to include the two tutorials developed for this project, “Creating an Account & Changing Account Settings” and “Adding an Observation:” http://www.inaturalist.org/pages/video+tutorials. Why iNaturalist? The iNaturalist app is available for both iOS (Apple) and Android devices, distinguishing it from apps such as Leafsnap that are currently available on only a single mobile platform. Like the two systems most similar to it (Project Noah and Project BudBurst, which will be discussed below), iNaturalist also provides a web browser interface, making the system not only operating-system independent, but also device independent, allowing contributors without mobile devices to use the system. The first iteration of iNaturalist was created by Nate Agrin, Jessica Kline, and Ken-ichi Ueda, information science graduate students at UC-Berkeley. iNaturalist is currently owned by iNaturalist, LLC, directed by Ueda and Scott Loarie, a research fellow at the Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford (http://www.inaturalist.org/pages/about). -

Inaturalist ( a Citizen Science Project and Online Social Network to Share and Annotate Observations of the Global Biodiversity

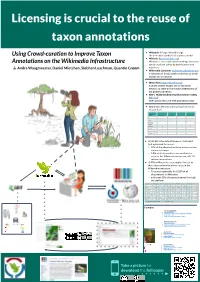

Licensing is crucial to the reuse of taxon annotations ● Wikipedia (<lang>.wikipedia.org) Using Crowd-curation to Improve Taxon the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit ● Wikidata (www.wikidata.org) Annotations on the Wikimedia Infrastructure Wikidata is a free and open knowledge base that can be read and edited by both humans and Andra Waagmeester, Daniel Mietchen, Siobhan Leachman, Quentin Groom machines. ● Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org) a collection of freely usable media files to which anyone can contribute ● iNaturalist (www.inaturalist.org) a citizen science project and online social network to share and annotate observations of the global biodiversity. ● GBIF | Global Biodiversity Information Facility (gbif.org) Open access resource with biodiversity data ● iNaturalist offers its users various licenses to choose from iNaturalist licenses Add to iNaturalist Add to Wikidata Add to Commons Add to Wikipedia CC0 + + + + CC-BY + + + + CC-BY-NC (default) + - - - CC-BY-SA + - + + CC-BY-ND + - - - CC-BY-NC-SA + - - - CC-BY-NC-ND + - - - ● CC-BY-NC is the default license in iNaturalist (not optimised for reuse) ○ 35% of the observations have a non-creative commons license ○ 6.8% of all observations are available for reuse in the Wikimedia ecosystem, still 1.9 million observations ● 0.47% of iNaturalist users apply a license to their observation that allows reuse in the Wikimedia ecosystem ○ They are responsible for 6.82% of all observations in iNaturalist ○ and cover 60% of species observed through the platform License Observations -

Vertebrate Fauna Assessment of Tower Hill/Pwakkenbak Reserve 15162

Vertebrate Fauna Assessment of Tower Hill/Pwakkenbak Reserve 15162 Angela Sanders, Ecologist, Albany WA for Great Southern Centre for Outdoor Recreation Excellence and Shire of Plantagenet March 2020 Contents 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Methods................................................................................................................................ 3 2.1 Desktop search ................................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Field assessment............................................................................................................... 4 3.0 Results .................................................................................................................................. 4 3.1 Desktop search ................................................................................................................. 4 3.2 Field assessment............................................................................................................... 5 3.2.1 Birds .......................................................................................................................... 5 3.2.2. Mammals.................................................................................................................. 6 4.0 Recommendations ............................................................................................................... -

An Introduction to Inaturalist 14 May 2020

Zoo Idaho Science Talk Pocatello, Idaho An Introduction to iNaturalist 14 May 2020 Charles R. (Chuck) Peterson Herpetology Laboratory Department of Biological Sciences Idaho Museum of Natural History Idaho State University [email protected] Zoo Idaho Science Talk Pocatello, Idaho An Introduction to iNaturalist 14 May 2020 Charles R. (Chuck) Peterson Herpetology Laboratory Department of Biological Sciences Idaho Museum of Natural History Idaho State University [email protected] Outline • Data Needs and Types • Crowdsourced and Citizen Science Data • About iNaturalist • Using the iNaturalist app • Projects • Applications The Need for Data • The Biodiversity Crisis • Causes • Habitat loss / modification • Overexploitation • Pollution • Climate Change • Introduced Species • Disease • “Without quality data, problems go undetected” – Todd Wilkinson The Need for Data • Need more current information on the occurrence and distribution of nongame species to identify conservation problems. • Examples: • Idaho State Wildlife Action Plan (IDFG) 2005 / 2015 • ESA Listing Decisions (US FWS) • Columbia Spotted Frog • Western Toad • Northern Leopard Frog Where do biodiversity data come from? • Literature • Museums • Surveys • Contributed Observations • Terminology • Traditional • Citizen Science • Crowdsourced • Problems • Identification accuracy • Location accuracy • Convenience of submission Crowdsourced and Citizen Science Data Crowdsourcing Citizen Science • The practice of obtaining needed data • The collection and analysis of data by soliciting contributions -

Guide: Using Inaturalist with Students

Educator Guide: Using iNaturalist with Students iNaturalist is an free observation platform that acts as a place for people to record biodiversity observations, interact with other enthusiasts, and learn about organisms. Observations from iNaturalist can also contribute to biodiversity science by being shared with open science projects such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL). Scientists (and anyone) can freely access and use these data to address their research questions. iNaturalist is designed to be used by anyone, and with practice can be a great tool for students. This guide will walk you through recommendations for the best ways to use iNaturalist with students in formal or informal settings so they learn from the experience and contribute high-quality observations to the iNaturalist community. Before the City Nature Challenge Build a Foundation in iNaturalist Before Engaging Students It’s important to have a strong foundation using iNaturalist before introducing it to students. Spend time viewing tutorials, reading the iNaturalist Teacher’s Guide, making observations, and interacting with the iNaturalist community. The iNaturalist team recommends making 20-30 observations in the area where you plan to bring students or participants so you learn the technology and become familiar with some of the organisms your students may find. Set up iNaturalist Account(s) Users must be at least 13 years old to have an iNaturalist.org account. Educators must decide if they want students to have their own accounts or if they want a class or group account that all students have access to. There are pros and cons for both options. -

Integrating Technology Into Glacier National Park's Common Loon

Integrating Technology Into Glacier National Park’s Common Loon Citizen Science Project An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by Seth Chaves Kyle Lang Danielle Lavigne Molly Youngs Date: 11 October 2019 Report Submitted to: Professor Frederick Bianchi Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects. 1 Abstract The Common Loon Citizen Science Project in Glacier National Park is currently dealing with an uneven distribution of citizen scientists and the over involvement of staff. In order to mitigate this uneven distribution of citizen scientists, our group was asked to develop a tool that would allow citizen scientists to redirect their focus based on the number of surveys at different lakes. Our group developed a mapping application that displays basic information about the different lakes in the park so that citizen scientists can efficiently plan out their survey sites, decreasing the involvement of the staff and promoting a more even distribution of data points throughout the park’s lakes. 2 Acknowledgements This project was made possible due to the assistance from numerous groups and people. We have thoroughly enjoyed our past seven weeks in Glacier National Park. We are thankful for the opportunity that WPI’s IQP program provides for all students to gain real-world experience in exciting places across the globe. -

How to Use Inaturalist

How to Use iNaturalist Making & Sharing Nature Observations for Science Tania Homayoun, PhD, Texas Parks & Wildlife Overview • Texas Nature Trackers program & how we use iNaturalist –Texas Nature Trackers & Conservation Priorities –Texas Conservation Action Plan & Species of Greatest Conservation Need • Getting started with iNaturalist –iNaturalist website tour –Adding observations & Phone apps –Editing observations –Identifying observations –Projects & Places • How to get involved – citizen science and beyond Texas Nature Trackers & how it uses iNaturalist Derek Bridges, Flickr Creative Commons Texas Nature Trackers Program Goals: • Grow & enrich the naturalist community & experience • Contribute to research & inform conservation decisions Research & Naturalist Conservation Community Community Achievement Expertise Knowledge Data Products Impact Legitimacy Project Types Taxonomic Projects Place‐based Projects tpwd.texas.gov/trackers Nature Trackers Targets Nature Trackers Targets Targets by ecoregion SGCNs by county Texas Conservation Action Plan • Every state has a plan to address their Species of Greatest Conservation Need • More than 15,000 SGCN nation‐wide • 1,310 SGCN in Texas • Texas Conservation Action Plan provides a roadmap to recover our species of concern Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Common SGCN Population stability Threatened Endangered Time Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Not enough data = ? SGCN SGCN Population stability Threatened Endangered Time Who are our SGCNs? 1,310 birds, mammals, herps, -

Using Inaturalist in a Coverboard Protocol to Measure Data Quality: Suggestions for Project Design

Wittmann, J, et al. 2019. Using iNaturalist in a Coverboard Protocol to Measure Data Quality: Suggestions for Project Design. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 4(1): 21, pp. 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.131 METHOD Using iNaturalist in a Coverboard Protocol to Measure Data Quality: Suggestions for Project Design Julie Wittmann, Derek Girman and Daniel Crocker We evaluated the accuracy of data records generated by citizen scientist participants using iNaturalist in a coverboard sampling scheme, a common method to detect herpetofauna, involving 17 species of amphibians and reptiles. We trained and observed 10 volunteers working over an eight-month period at a study site in Sonoma County, California, USA. A total number of 1,169 observations were successfully uploaded to the iNaturalist database by volunteers including a new locality for Black Salamander. Volunteers were gener- ally successful in collecting and uploading data for verification but had more difficulties detecting smaller, camouflaged salamanders and photographing quick-moving lizards. Errors associated with uploading smart- phone data were reduced with volunteer experience. We evaluated all observations and determined that 82% could be verified to the species level based on the photograph. Forty-five percent of the observations made it to the iNaturalist “research grade” quality using their crowdsourcing tools. Independently we eval- uated the crowdsourcing accuracy of the research grade observations and found them to be 100% accurate to the species level. A variety of factors (herpetofauna group, species, photograph quality) played a role in determining whether observations were elevated to research grade. Volunteer screening and training pro- tocols emphasizing smartphones that have appropriate battery and data storage capacity eliminated some issues. -

Plant Science Bulletin Spring 2016 Volume 62 Number 1

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN SPRING 2016 VOLUME 62 NUMBER 1 A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA SPECIAL FEATURE: BOTANICALPLANTS SOCIETY Grant RecipientsENGAGEMENT and Mentors IN CITIZEN Gather atSCIENCE Botany 2015! IN THIS ISSUE... Hawai‘i botanists com- American Journal of Botany Introducing BSA’s Education plete assessments for kicks off 2016 with two Special Technology Coordinator, Dr. IUCN Red List of Threat- Issues.... p.7 Jodi Creasap Gee... p. 34 ened Species .... p. 4 From the Editor PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN Greetings! Editorial Committee It is fair to say that one of the current trends in Volume 62 science is the application of “Citizen Science.” Re- searchers are relying more and more on amateur scientists and the general public for data collection and increasingly incorporating crowd-sourced data into their analyses. However, this movement has not been without its challenges and skeptics. In this issue of Plant Science Bulletin, I am pleased L.K. Tuominen (2016) to present a special feature on Citizen Science as it Department of Natural Science relates to botany. On page 10, Maura Flannery de- Metropolitan State University St. Paul, MN 55106 scribes Citizen Science, discusses the response of [email protected] the botanical community, and argues the impor- tance of these kinds of projects for plant research. Following this (page 16) are brief descriptions of projects in which BSA members and botanical in- stitutions have been involved. I want to send a spe- cial “thank you” to those of you who responded Daniel K. Gladish (2017) to my request for these project descriptions that Department of Biology & exemplify the types of citizen science that we, as The Conservatory botanists, can undertake.