The Business Plot Smedley D. Butler, Anti-Democratic Dissidence, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2/21-VFW Newsletter (Page 1)

February 21 General Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller 14631 MINNIEVILLE ROAD • DALE CITY, VIRGINIA 22193 • 703.670.4124 www.vfw1503.org CANTEEN HOURS: Sunday / Monday / Wednesday 12 Noon - 11 PM Tuesday / Thursday / Saturday 12 Noon - 12 Midnight • Friday 12 Noon - 2 AM COMMANDER’S CORNER POST OFFICERS Post Commander . Tom Levitt Comrades and Auxiliary Members, Senior Vice . Bernie Carter We end our first month of the new year Junior Vice . Ben Guinan hoping that things are beginning to turn around Quartermaster . Tim Brown Judge Advocate. Star Martinez for us in this pandemic as we see vaccines being Surgeon . Robert Adamczyk administered. Despite a significant spike in COVID cases over the Chaplain. Ed Bennett holidays there is a belief that the vaccine will help us flatten the 3 Year Trustee . Tom Gimble 2 Year Trustee . Ron Laney curve and begin trending downward. I know we will all be happy 1 Year Trustee. John Dodge to get back some normalcy in our lives and at our post!! Adjutant . Randy Coker This past month we celebrated the life of Martin Luther King Jr. Service Officer . Carl Richardson Asst. Service Officer . Tami Brown and his contributions to the civil rights movement. Normally on House Committee Chairman. Joe Saitta that day we host a meal in his honor which we failed to do this Past Commander . Thomas Williams, Jr. year. An honest mistake, but a mistake nonetheless. As the Commander everything that happens or fails to happen in the post is my responsibility. For this failure I take responsibility and apologize to all who may have felt slighted or offended. -

Was American Expansion Abroad Justified?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 8th Grade American Expansion Inquiry Was American Expansion Abroad Justified? Newspaper front page about the explosIon of the USS Maine, an AmerIcan war shIp. New York Journal. “DestructIon of the War ShIp Maine was the Work of an Enemy,” February 17, 1898. PublIc domain. Available at http://www.pbs.org/crucIble/headlIne7.html. Supporting Questions 1. What condItIons Influenced the United States’ expansion abroad? 2. What arguments were made In favor of ImperIalIsm and the SpanIsh-AmerIcan War? 3. What arguments were made In opposItIon to ImperIalIsm and the SpanIsh-AmerIcan War? 4. What were the results of the US involvement in the Spanish-AmerIcan War? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 8th Grade American Expansion Inquiry Was American Expansion Abroad Justified? 8.3 EXPANSION AND IMPERIALISM: BegInning In the second half of the 19th century, economIc, New York State Social polItIcal, and cultural factors contrIbuted to a push for westward expansIon and more aggressIve Studies Framework Key UnIted States foreIgn polIcy. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting EVidence Geographic Reasoning Economics and Economic Systems Staging the Question UNDERSTAND Discuss a recent mIlItary InterventIon abroad by the UnIted States. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 What condItIons Influenced What arguments were -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

The American Liberty League and the Rise of Constitutional Nationalism Jared Goldstein Roger Williams University School of Law

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Law Faculty Scholarship Law Faculty Scholarship Winter 2014 The American Liberty League and the Rise of Constitutional Nationalism Jared Goldstein Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/law_fac_fs Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Jared A. Goldstein, The American Liberty League and the Rise of Constitutional Nationalism, 86 Temp. L. Rev. 287, 330 (2014) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Scholarship at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: Jared A. Goldstein, The American Liberty League and the Rise of Constitutional Nationalism, 86 Temp. L. Rev. 287, 330 (2014) Provided by: Roger Williams University School of Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Thu Nov 16 15:40:33 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device THE AMERICAN LIBERTY LEAGUE AND THE RISE OF CONSTITUTIONAL NATIONALISM JaredA. Goldstein* This Article launches a project to identify constitutional nationalism-the conviction that the nation'sfundamentalvalues are embodied in the Constitution-as a recurring phenomenon in American public life that has profoundly affected both popular and elite understandingof the Constitution. -

Eligibility Guide.Pdf

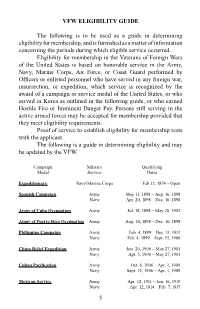

VFW ELIGIBILITY GUIDE The following is to be used as a guide in determining eligibility for membership, and is furnished as a matter of information concerning the periods during which eligible service occurred. Eligibility for membership in the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States is based on honorable service in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard performed by Officers or enlisted personnel who have served in any foreign war, insurrection, or expedition, which service is recognized by the award of a campaign or service medal of the United States, or who served in Korea as outlined in the following guide, or who earned Hostile Fire or Imminent Danger Pay. Persons still serving in the active armed forces may be accepted for membership provided that they meet eligibility requirements. Proof of service to establish eligibility for membership rests with the applicant. The following is a guide in determining eligibility and may be updated by the VFW. Campaign Military Qualifying Medal Service Dates Expeditionary Navy/Marine Corps Feb 12, 1874 – Open Spanish Campaign Army May 11, 1898 – Aug. 16, 1898 Navy Apr. 20, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Army of Cuba Occupation Army Jul. 18, 1898 – May 20, 1902 Army of Puerto Rico Occupation Army Aug. 14, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Philippine Campaign Army Feb. 4, 1899 – Dec. 31, 1913 Navy Feb. 4, 1899 – Sept. 15, 1906 China Relief Expedition Army Jun. 20, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Navy Apr. 5, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Cuban Pacification Army Oct. 6, 1906 – Apr. 1, 1909 Navy Sept. 12, 1906 – Apr. -

Whpr19740819-010

-., f'. Digitized from Box 1 of the White House Press Releases at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUGUST 19, 1974 , OFFICE OF THE WHITE HOUSE PRESS SECRETARY (Chicago, Illinois) THE WHITE HOUSE ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT TO THE 7STH CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS or FOREIGN WARS CONRAD HILTON HOTEL 11:38 A.M. CDT Commander Ray Soden, Governor Walker, my former members or former colleagues of the United States Congress, my fellow members of the Veterans of Foreign Wars: Let me express my deepest gratitude for your extremely warm welcome and may I say to Mayor Daley, and to all the wonderful people of Chicago who have done an unbelievable job in welcoming Betty and myself to Chicago, we are most grateful. I have a sneaking suspicion that Mayor Daley and the people of Chicago knew that Betty was born in Chicago. Needless to say, I deeply appreciate your medal and the citation on my first trip out of Washington as your President. I hope that in the months ahead I can justify your faith in making the citation and the award available to me. It is good to be back in Chicago among people from all parts of our great Nation to take part in this 75th Annual convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. As a proud member of Old Kent Post VFW 830, let me talk today about some of the work facing veterans - and all Americans -- the issues of world peace and national unity. Speaking of national unity,. let me.quick;Ly point out that I am also a proud member of the American Legion and the AMVETS. -

American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: an Appraisal of Alexis De Tocqueville’S Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and the Post-World War II Welfare State John P. Varacalli The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AMERICAN CIVIL ASSOCIATIONS AND THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: AN APPRAISAL OF ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE’S DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA (1835- 1840) APPLIED TO FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II WELFARE STATE by JOHN P. VARACALLI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 JOHN P. VARACALLI All Rights Reserved ii American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Post World War II Welfare State by John P. Varacalli The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ______________________ __________________________________________ Date David Gordon Thesis Advisor ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. -

Remarks at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention in Phoenix, Arizona August 17, 2009

Aug. 15 / Administration of Barack Obama, 2009 NOTE: The President spoke at 3:44 p.m. at troduced the President, his wife Sonji, and Central High School. In his remarks, he re- their son Thomas; Tilman Bishop, vice chair of ferred to Nathan Wilkes, principal network ar- the board of regents, University of Colorado; chitect, Virtela Communications, Inc., who in- and Sen. Johnny Isakson. Remarks at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention in Phoenix, Arizona August 17, 2009 Thank you. Please, be seated. Thank you so our harbor was bombed, you battled across much. Commander Gardner, thank you for rocky Pacific islands and stormed the beaches your introduction and for your lifetime of ser- of Europe, marching across a continent—my vice. I was proud to welcome Glen and your own grandfather and uncle among your executive director, Bob Wallace, to the Oval ranks—liberating millions and turning ene- Office just before the Fourth of July, and I mies into allies. look forwarding to working with your next When communism cast its shadow across so commander, Tommy Tradewell. I want to also much of the globe, you stood vigilant in a long acknowledge Jean Gardner and Sharon cold war, from an airlift in Berlin to the moun- Tradewell, as well as Dixie Hild and Jan Tittle tains of Korea to the jungles of Vietnam. and all the spouses and family of the Ladies When that cold war ended and old hatreds Auxiliary. America honors your service as well. emerged anew, you turned back aggression Also Governor Jan Brewer is here, of Arizo- from Kuwait to Kosovo. -

Inner Light – Good and Evil – Open and Hidden

2 n d e d n © T G 2 0 2 1 £ 1 0 v i a 1 b i l d e r b e r g . o extracts companion to The Siege Of Heaven with my thoughts on solutions – ed.on Heaven The solutions – with my thoughts Siege Of toextracts companion under guise of a never-ending pandemic, modelled on their never ending war on terror. terror. endingwar never pandemic, theiron modelled on a guiseofunder never-ending legallyandtaken up,overbeingboughtfreedom as mediaFood is thought for all ismySo career!this secretRothschilds Victor on Fifth ‘Thesee Man’ Please financially. Since the Anglo-Zionist empire has been defeated militarilyinMiddle defeated Russia, been East Anglo-Zionist by empire hasthe Sincethe eyecrushing their journalism in the they’ve own population, to subduing their turned surveillance bringing to the authoritarian state west, – the China Assange Julian ofperson Portland Communications boss George Pascoe-Watson with Lord with and Bethell who funded Pascoe-Watson Portland George Communications boss were leadershipcampaign Tory 2019 Hancock’s Matthealth managed UK secretary the plandemic.steeringCovidthe start of ministerial discussions from Generally short extracts from longer works - published in the midst of November 2020’s published - November 2020’s longer in the midst of extracts works Generally from short Pharma Banking, Bigchum lobbyists Arms, It becomes boguslight’. ‘lockdown clear UK r g 2 n d e d n © T G 2 0 2 1 £ 1 0 v i a 2 b i l All reserved rights d ISBN 0 9528070 8 4 e The SiegeThe Of Reader Heaven Copyright Tony Gosling 2021 Tony Copyright a magazine,a newspaper or broadcast r Printed and bound in the USA by lulu.com andPrinted the bound in USA b Address: 17-25, Jamaica Street, Bristol, BS2 8JP The moral rightsThe author of the been have asserted e post-medieval articles on occult political and spiritual power r First published in published BritainFirst Great in by Gosling publishing 2021 g A catalogue for this record book is available the Library from British A pleased make necessary to the arrangements at earliest the opportunity. -

Pizzagate / Pedogate, a No-Nonsense Fact-Filled Reader

Pizzagate / Pedogate A No-nonsense Fact-filled reader Preface I therefore determine that serious human rights abuse and corruption around the world constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States, and I hereby declare a national emergency to deal with that threat. —Trump Executive Order 13818, Dec. 20, 2017 Pizzagate means many things to many people, the angle of the lens may be different, but the focus zeros in on a common body of incontestable facts. The fruit of top researchers collected in this reader allows you to compare, correlate and derive a flexible synthesis to suit your needs. An era of wild contradiction is upon us in the press. The psychopathic rumblings that pass for political discourse bring the artform of infotainment to a golden blossoming. A bookstore display table featuring The Fixers; The Bottom-Feeders, Crooked Lawyers, Gossipmongers, and Porn Stars Who Created the 45th President versus Witch Hunt; The Story of the Greatest Mass Delusion in American Political History are both talking about the same man, someone who paid for his campaign out of his own pocket. There were no big donors from China and the traditional bank of puppeteers. This created a HUGE problem, one whose solution threatened the money holders and influence peddlers. New leadership and a presidential order that threw down the gauntlet, a state of emergency, seeded the storm clouds. The starting gun was fired, all systems were go, the race had begun. FISAs and covert operations sprang into action. The envelopes are being delivered, the career decisions are being made, should I move on or stay the course. -

Identifying and Countering FAKE NEWS Mark Verstraete1, Derek E

Identifying and Countering FAKE NEWS Mark Verstraete1, Derek E. Bambauer2, & Jane R. Bambauer3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Fake news has become a controversial, highly contested issue recently. But in the public discourse, “fake news” is often used to refer to several different phenomena. The lack of clarity around what exactly fake news is makes understanding the social harms that it creates and crafting solutions to these harms difficult. This report adds clarity to these discussions by identifying several distinct types of fake news: hoax, propaganda, trolling, and satire. In classifying these different types of fake news, it identifies distinct features of each type of fake news that can be targeted by regulation to shift their production and dissemination. This report introduces a visual matrix to organize different types of fake news and show the ways in which they are related and distinct. The two defining features of different types of fake news are 1) whether the author intends to deceive readers and 2) whether the motivation for creating fake news is financial. These distinctions are a useful first step towards crafting solutions that can target the pernicious forms of fake news (hoaxes and propaganda) without chilling the production of socially valuable satire. The report emphasizes that rigid distinctions between types of fake news may be unworkable. Many authors produce fake news stories while holding different intentions and motivations simultaneously. This creates definitional grey areas. For instance, a fake news author can create a story as a response to both financial and political motives. Given 1 Fellow in Privacy and Free Speech, University of Arizona, James E. -

Unified Conspiracy Theory - Rationalwiki

Unified Conspiracy Theory - RationalWiki http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Unified_Conspiracy_Theory Unified Conspiracy Theory From RationalWiki The Unified Conspiracy Theory is a conspiracy theory, popular with Some dare call it some paranoids, that all of reality is controlled by a single evil entity that has it in for them. It can be a political entity, like "The Illuminati", or a Conspiracy metaphysical entity, like Satan, but this entity is responsible for the creation and management of everything bad. The Church of the SubGenius has adopted this notion as fundamental dogma. Michael Barkun coined the term "superconspiracy" to refer the idea that the world is controlled by an interlocking hierarchy of conspiracies. Secrets revealed! Similarly, Michael Kelly, a neoconservative journalist, coined the term America Under Siege "fusion paranoia" in 1995 to refer to the blending of conspiracy theories CW Leonis of the left with those of the right into a unified conspiratorial Doug Rokke [1] worldview. Guillotine List of conspiracy theories This was played with in the Umberto Eco novel Foucault's Pendulum , in Majestic 12 which the characters make up a conspiracy theory like this...except it Pravda.ru turns out to be true. Shakespeare authorship Society of Jesus Tupac Shakur Contents v - t - e (http://rationalwiki.org /w/index.php?title=Template:Conspiracynav& action=edit) 1 See also 1.1 (In)Famous proponents 2 External links 3 Footnotes See also List of Conspiracy Theories Maltheism Crank magnetism (In)Famous proponents David Icke Alex Jones Lyndon LaRouche Jeff Rense 1 of 2 7/19/2012 8:24 PM Unified Conspiracy Theory - RationalWiki http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Unified_Conspiracy_Theory External links Flowchart guide to the grand conspiracy (http://farm4.static.flickr.com /3048/2983450505_34b4504302_o.png) Conspiracy Kitchen Sink (http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ConspiracyKitchenSink) , TV Tropes Footnotes 1.