Appendixes Appendix 1 on Mackenzie’S Historical Enquiries: a Memorandum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2216Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/150023 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘AN ENDLESS VARIETY OF FORMS AND PROPORTIONS’: INDIAN INFLUENCE ON BRITISH GARDENS AND GARDEN BUILDINGS, c.1760-c.1865 Two Volumes: Volume I Text Diane Evelyn Trenchard James A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Department of History of Art September, 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………. iv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………… vi Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………. viii . Glossary of Indian Terms ……………………………………………………....... ix List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………... xvii Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 1 1. Chapter 1: Country Estates and the Politics of the Nabob ………................ 30 Case Study 1: The Indian and British Mansions and Experimental Gardens of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal …………………………………… 48 Case Study 2: Innovations and improvements established by Sir Hector Munro, Royal, Bengal, and Madras Armies, on the Novar Estate, Inverness, Scotland …… 74 Case Study 3: Sir William Paxton’s Garden Houses in Calcutta, and his Pleasure Garden at Middleton Hall, Llanarthne, South Wales ……………………………… 91 2. Chapter 2: The Indian Experience: Engagement with Indian Art and Religion ……………………………………………………………………….. 117 Case Study 4: A Fairy Palace in Devon: Redcliffe Towers built by Colonel Robert Smith, Bengal Engineers ……………………………………………………..…. -

LHA Recuritment Visakhapatnam Centre Screening Test Adhrapradesh Candidates at Mudasarlova Park Main Gate,Visakhapatnam.Contact No

LHA Recuritment Visakhapatnam centre Screening test Adhrapradesh Candidates at Mudasarlova Park main gate,Visakhapatnam.Contact No. 0891-2733140 Date No. Of Candidates S. Nos. 12/22/2014 1300 0001-1300 12/23/2014 1300 1301-2600 12/24/2014 1299 2601-3899 12/26/2014 1300 3900-5199 12/27/2014 1200 5200-6399 12/28/2014 1200 6400-7599 12/29/2014 1200 7600-8799 12/30/2014 1177 8800-9977 Total 9977 FROM CANDIDATES / EMPLOYMENT OFFICES GUNTUR REGISTRATION NO. CASTE GENDER CANDIDATE NAME FATHER/ S. No. Roll Nos ADDRESS D.O.B HUSBAND NAME PRIORITY & P.H V.VENKATA MUNEESWARA SUREPALLI P.O MALE RAO 1 1 S/O ERESWARA RAO BHATTIPROLU BC-B MANDALAM, GUNTUR 14.01.1985 SHAIK BAHSA D.NO.1-8-48 MALE 2 2 S/O HUSSIAN SANTHA BAZAR BC-B CHILAKURI PETA ,GUNTUR 8/18/1985 K.NAGARAJU D.NO.7-2-12/1 MALE 3 3 S/O VENKATESWARULU GANGANAMMAPETA BC-A TENALI. 4/21/1985 SHAIK AKBAR BASHA D.NO.15-5-1/5 MALE 4 4 S/O MAHABOOB SUBHANI PANASATHOTA BC-E NARASARAO PETA 8/30/1984 S.VENUGOPAL H.NO.2-34 MALE 5 5 S/O S.UMAMAHESWARA RAO PETERU P.O BC-B REPALLI MANDALAM 7/20/1984 B.N.SAIDULU PULIPADU MALE 6 6 S/O PUNNAIAH GURAJALA MANDLAM ,GUNTUR BC-A 6/11/1985 G.RAMESH BABU BHOGASWARA PET MALE 7 7 S/O SIVANJANEYULU BATTIPROLU MANDLAM, GUNTUR BC-A 8/15/1984 K.NAGARAJENDRA KUMAR PAMIDIMARRU POST MALE 8 8 S/O. -

Madras Week ’19

August 16-31, 2019 MADRAS MUSINGS 7 MADRAS WEEK ’19 August 18 to August 25 Updated till August 12th August 17-18, 2019 Book Launch: Be the Book by Padmini Viswanathan and Aparna Kamakshi. Special Guests: Sriram V. (Writer and Entrepreneur), Seetha Exhibitions: Anna Nagar Exhibition: Panels on History of Anna Nagar Ravi (Kalki) at Odyssey, Adyar, 6.30 p.m. by Ar.Thirupurasundari, Anna Nagar Social History Group, Nam veedu, Nam oor, Nam Kadhai. Household Heritage Display by Mr. Venkatraman Talk: Devan-highlighting humour in Madras: Jayaraman Raghunathan. Prabakaran and Ar. Sivagamasundari T. Time : 10:00 am to 6:00 pm. ARKAY Convention Centre. Organised by Madras Local History Group. Venue: Joy of Books, Anna Nagar (JBAN), T 88, 5th Main Road, Anna 6.45 p.m. Nagar, Chennai 600 040. For details, registrations and other enquiries: phone : 00-91-9444253532. Email: [email protected]. Competition: Social History of Anna Nagar through Power point/ Scrapbook. Make your Social history album/Scrap book. Age: 8-16 August 17, 2019 (individual) Submission: on or before August 15th 2019; Event will be held on August 17, 2019. Naduvakkarai to Anna Nagar Heritage Walk: (the Tower Park – Ayyapan Start with a 4 generation family tree (minimum), add pictures, plan of temple side entrance) organised by Nam veedu, Nam oor, Nam Kadhai. your house (before and now), write stories, add function invitations, 7:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. For further details, registrations and other postcards, sketches etc. – and how your family moved to Anna Nagar, enquiries email: [email protected]; phone: 00-91-9444253532 when? Why? How your family history is related to Anna Nagar. -

History of the Mackenzies Alexander Mackenzie

History Of The Mackenzies Alexander Mackenzie THE HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES. ORIGIN. THE CLAN MACKENZIE at one time formed one of the most powerful families in the Highlands. It is still one of the most numerous and influential, and justly claims a very ancient descent. But there has always been a difference of opinion regarding its original progenitor. It has long been maintained and generally accepted that the Mackenzies are descended from an Irishman named Colin or Cailean Fitzgerald, who is alleged but not proved to have been descended from a certain Otho, who accompanied William the Conqueror to England, fought with that warrior at the battle of Hastings, and was by him created Baron and Castellan of Windsor for his services on that occasion. THE REPUTED FITZGERALD DESCENT. According to the supporters of the Fitzgerald-Irish origin of the clan, Otho had a son Fitz-Otho, who is on record as his father's successor as Castellan of Windsor in 1078. Fitz-Otho is said to have had three sons. Gerald, the eldest, under the name of Fitz- Walter, is said to have married, in 1112, Nesta, daughter of a Prince of South Wales, by whom he also had three sons. Fitz-Walter's eldest son, Maurice, succeeded his father, and accompanied Richard Strongbow to Ireland in 1170. He was afterwards created Baron of Wicklow and Naas Offelim of the territory of the Macleans for distinguished services rendered in the subjugation of that country, by Henry II., who on his return to England in 1172 left Maurice in the joint Government. -

Professor Horace Hayman Wilson, Ma, Frs

PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN: PROFESSOR HORACE HAYMAN WILSON, MA, FRS “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project People of A Week and Walden HDT WHAT? INDEX PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN: HORACE HAYMAN WILSON A WEEK: A Hindoo sage said, “As a dancer, having exhibited herself PEOPLE OF to the spectator, desists from the dance, so does Nature desist, A WEEK having manifested herself to soul —. Nothing, in my opinion, is more gentle than Nature; once aware of having been seen, she does not again expose herself to the gaze of soul.” HORACE HAYMAN WILSON HENRY THOMAS COLEBROOK WALDEN: Children, who play life, discern its true law and PEOPLE OF relations more clearly than men, who fail to live it worthily, WALDEN but who think that they are wiser by experience, that is, by failure. I have read in a Hindoo book, that “there was a king’s son, who, being expelled in infancy from his native city, was brought up by a forester, and, growing up to maturity in that state imagined himself to belong to the barbarous race with which he lived. One of his father’s ministers having discovered him, revealed to him what he was, and the misconception of his character was removed, and he knew himself to be a prince. So soul,” continues the Hindoo philosopher, “from the circumstances in which it is placed, mistakes its own character, until the truth is revealed to it by some holy teacher, and then it knows itself to be Brahme.” I perceive that we inhabitants of New England live this mean life that we do because our vision does not penetrate the surface of things. -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

Praktiser De Menneskelige Værdier Af Bhagavan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Dato : 22. november 2006. Sted : Prasanthi Nilayam. Anledning : Åbningstale på Sathya Sai’s internationale sportscenter. Ordliste : De danske ord der er understreget i teksten, er at finde i ordlisten. Disse danske ord er oversættelser af sanskrit-ord, som også nævnes i ordlisten. Dette giver læseren mulighed for selv at undersøge sanskrit-ordenes dybere betydning. Praktiser de menneskelige værdier af Bhagavan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Nu til dags føler mennesket sig stolt over, at han behersker mange grene inden for viden, og at han har studeret mange emner. Men mennesket forsøger ikke at forstå uddannelsens inderste væsen. I vore dage er lærdom begrænset til blot at omfatte fysiske og verdslige aspekter, og moralske, etiske og åndelige aspekter tilsidesættes. I dag gør forældre sig ihærdige anstrengelser for at skaffe deres børn en uddannelse. Men ingen prøver at forstå uddannelsens sande betydning. Folk tror, at de der kan tale meningsfuldt og sigende, og som har studeret mange bøger, er yderst veluddannede. Men sandheden er, at det blot viser, at de har viden om alfabetet og intet andet. Ren og skær viden om alfabetet kan ikke kaldes uddannelse. Udover at have kendskab til bogstaver, er man nødt til at kende betydningen af de ord og sætninger, som bogstaverne sammensætter. Idet han var klar over denne sandhed, indkaldte kong Krishnadevaraya til et stort møde. Han rejste et spørgsmål over for de forsamlede digtere og lærde. Til stede i denne forsamling var også otte berømte digtere fra Krishnadevaraya’s hof. De var kendt som Aashta diggajas. De var: Allasani Peddana, Nandi Thimmana, Madayyagari Mallana, Dhurjati, Ayyalaraju Ramabhadrudu, Pingali Surana, Ramarajabhushanudu og Tenali Ramakrishna. -

Sri Sathya Sai Speaks, Vol 39 (2006) Divine Discourses of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Sri Sathya Sai Speaks, Vol 39 (2006) Divine Discourses of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Index Of Discourses 1. Discharge your duties with a sense of surrender to God ...................................... 2 2. Control of Senses is the Real Sadhana ................................................................. 13 3. Limit not the all-pervading Brahman with Names and Forms ......................... 26 4. Atma is the Nameless, Formless Divinity ............................................................. 39 5. Experience the Sweetness of Rama's Name ......................................................... 51 6. Happiness Is Holiness ............................................................................................ 63 7. Do Not Burden Yourself With Limitless Desires ................................................ 74 8. Mother's love has immense power ....................................................................... 84 9. Attain enlightenment by renouncing desires ....................................................... 95 10. Selfless service to society is true sadhana .......................................................... 105 11. The youth should follow the path of sathya and dharma ................................. 113 12. Develop Broad-mindedness and Live in Bliss ................................................... 122 13. Give up selfishness and strive for self-realisation ............................................. 132 14. Love of God is True Education .......................................................................... -

Resisting Radical Energies:Walter Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish

Cycnos 18/06/2014 10:38 Cycnos | Volume 19 n°1 Résistances - Susan OLIVER : Resisting Radical Energies:Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Borderand the Re-Fashioning of the Border Ballads Texte intégral Walter Scott conceived of and began his first major publication, the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, in the early 1790s. Throughout that decade and into the first three years of the nineteenth century, he worked consistently at accumulating the substantial range of ballad versions and archival material that he would use to produce what was intended to be an authoritative and definitive print version of oral and traditional Borders ballad culture. For the remainder of his life Scott continued to write and speak with affection of his “Liddesdale Raids,” the ballad collecting and research trips that he made into the Borders country around Liddesdale mainly during the years 1792–99. J. G. Lockhart, his son-in-law and biographer, describes the period spent compiling the Minstrelsy as “a labour of love truly, if ever there was,” noting that the degree of devotion was such that the project formed “the editor’s chief occupation” during the years 1800 and 1801. 1 At the same time, Lockhart takes particular care to state that the ballad project did not prevent Scott from attending the Bar in Edinburgh or from fulfilling his responsibilities as Sheriff Depute of Selkirkshire, a post he was appointed to on 16th December 1799. 2 The initial two volumes of the Minstrelsy, respectively sub-titled “Historical Ballads” and “Romantic Ballads,” were published in January 1802. 3 A third volume, supplementary to the first two, was published in May 1803. -

Interpreting an Architectural Past Ram Raz and the Treatise in South Asia Author(S): Madhuri Desai Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol

Interpreting an Architectural Past Ram Raz and the Treatise in South Asia Author(s): Madhuri Desai Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 71, No. 4, Special Issue on Architectural Representations 2 (December 2012), pp. 462-487 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jsah.2012.71.4.462 Accessed: 02-07-2016 12:13 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians This content downloaded from 160.39.4.185 on Sat, 02 Jul 2016 12:13:51 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Figure 1 The relative proportions of parts of columns (from Ram Raz, Essay on the Architecture of the Hindus [London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1834], plate IV) This content downloaded from 160.39.4.185 on Sat, 02 Jul 2016 12:13:51 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Interpreting an Architectural Past Ram Raz and the Treatise in South Asia madhuri desai The Pennsylvania State University he process of modern knowledge-making in late the design and ornamentation of buildings (particularly eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century South Hindu temples), was an intellectual exercise rooted in the Asia was closely connected to the experience of subcontinent’s unadulterated “classical,” and more signifi- T 1 British colonialism. -

Clerks (Ibps Clerk Ix Process) - Notice Dtd 12.09.2019 List of Candidates Provisionally Selected and Allotted by Ibps for Post of Clerk

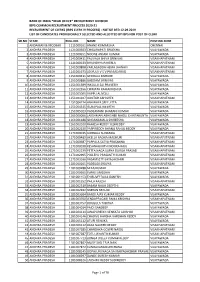

BANK OF INDIA *HEAD OFFICE* RECRUITMENT DIVISION IBPS COMMON RECRUITMENT PROCESS 2020-21 RECRUITMENT OF CLERKS (IBPS CLERK IX PROCESS) - NOTICE DTD 12.09.2019 LIST OF CANDIDATES PROVISIONALLY SELECTED AND ALLOTTED BY IBPS FOR POST OF CLERK SR.NO STATE ROLL.NO. NAME POSTING ZONE 1 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR 1111000161 ANAND KUMAR JHA CHENNAI 2 ANDHRA PRADESH 1121000303 CHIGURUPATI SRILEKHA VIJAYAWADA 3 ANDHRA PRADESH 1121000651 NOONE ANJANI KUMAR VIJAYAWADA 4 ANDHRA PRADESH 1141000411 PALIVALA SHIVA SRINIVAS VISAKHAPATNAM 5 ANDHRA PRADESH 1141000633 BHAVISHYA PAKERLA VISAKHAPATNAM 6 ANDHRA PRADESH 1141000808 YARLAGADDA HEMA JAHNAVI VISAKHAPATNAM 7 ANDHRA PRADESH 1141001673 JOSYULA V S V PRASADARAO VISAKHAPATNAM 8 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151000411 GEDDALA KISHORE VIJAYAWADA 9 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151000886 GADDAM SRINIVAS VIJAYAWADA 10 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151001389 INKOLLU SAI PRAVEEN VIJAYAWADA 11 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151002556 CHIMATA RAMAKRISHNA VIJAYAWADA 12 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151003005 VUPPU ALIVELU VIJAYAWADA 13 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151004107 GUNTUR ABHISHEK VISAKHAPATNAM 14 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151004274 ABHINAYA SREE JITTA VIJAYAWADA 15 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151004515 ISUKAPALLI KEERTHI VIJAYAWADA 16 ANDHRA PRADESH 1151005023 VADLAMANI BHARANI KUMAR VIJAYAWADA 17 ANDHRA PRADESH 1161000066 LAKSHMAN ABHISHEK NAIDU CHINTAKUNTA VIJAYAWADA 18 ANDHRA PRADESH 1161001188 SINGANAMALA SHIREESHA VIJAYAWADA 19 ANDHRA PRADESH 1161002020 RAMESH REDDY YESIREDDY VIJAYAWADA 20 ANDHRA PRADESH 1161002630 PAPPIREDDY BHANU RAHUL REDDY VIJAYAWADA 21 ANDHRA PRADESH 1171000015 GUBBALA SUNANDA VISAKHAPATNAM -

Indian Angles

Introduction The Asiatic Society, Kolkata. A toxic blend of coal dust and diesel exhaust streaks the façade with grime. The concrete of the new wing, once a soft yellow, now is dimmed. Mold, ever the enemy, creeps from around drainpipes. Inside, an old mahogany stair- case ascends past dusty paintings. The eighteenth-century fathers of the society line the stairs, their white linen and their pale skin yellow with age. I have come to sue for admission, bearing letters with university and government seals, hoping that official papers of one bureaucracy will be found acceptable by an- other. I am a little worried, as one must be about any bureaucratic encounter. But the person at the desk in reader services is polite, even friendly. Once he has enquired about my project, he becomes enthusiastic. “Ah, English language poetry,” he says. “Coleridge. ‘Oh Lady we receive but what we give . and in our lives alone doth nature live.’” And I, “Ours her wedding garment, ours her shroud.” And he, “In Xanadu did Kublai Khan a stately pleasure dome decree.” “Where Alf the sacred river ran,” I say. And we finish together, “down to the sunless sea.” I get my reader’s pass. But despite the clerk’s enthusiasm, the Asiatic Society was designed for a different project than mine. The catalog yields plentiful poems—in manuscript, on paper and on palm leaves, in printed editions of classical works, in Sanskrit and Persian, Bangla and Oriya—but no unread volumes of English language Indian poetry. In one sense, though, I have already found what I need: that appreciation of English poetry I have encountered everywhere, among strangers, friends, and col- leagues who studied in Indian English-medium schools.