Research.Pdf (947.2Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration March 30, 2018 9 A.M

Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration March 30, 2018 9 a.m. – 12 p.m. Martin’s West, Baltimore, MD Hosted by Gilchrist Presenting Sponsor: Alban CAT “A Grateful Nation Thanks and Honors You.” WE ARE PROUD TO HONOR THE VIETNAM VETS TODAY A VETERAN OWNED COMPANY Heavy equipment, compact construction equipment, power generation, and micro-grid solutions for the Mid-Atlantic & DC Metro Areas 800-443-9813 | www.albancat.com 2 We Honor Veterans Thank you for joining us at Gilchrist’s inaugural Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration—a day to honor and thank the men and women in our community who served during the Vietnam War. Gilchrist is a nationally recognized nonprofit that provides care and support for people with serious illness through the end of life, through elder medical care, counseling and support, and hospice care. Many of Gilchrist’s hospice patients are veterans and many of them served during the Vietnam era. Gilchrist’s Welcome Home celebration honors the veterans in our care as well as all of the veterans in our community, and coincides with Maryland’s Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day, signed into law by Governor Larry Hogan in 2015. This celebration is one of the many ways Gilchrist recognizes the unique needs of veterans and thanks them for their sacrifice and service to our country. We are proud to honor those who have served in the United States Armed Forces. gilchristcares.org 3 Our Sponsors We are grateful to the following sponsors for their support of this event. Four Star Alban CAT Three Star Jonathan and Jennifer Murray Anonymous Donor Two Star Marietta and Ed Nolley Martin’s West Webb Mason Colonel H. -

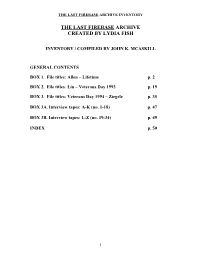

The Last Firebase Archive Created by Lydia Fish

THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE INVENTORY THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE CREATED BY LYDIA FISH INVENTORY / COMPILED BY JOHN K. MCASKILL GENERAL CONTENTS BOX 1. File titles: Allen – Lifetime p. 2 BOX 2. File titles: Lin – Veterans Day 1993 p. 19 BOX 3. File titles: Veterans Day 1994 – Ziegele p. 35 BOX 3A. Interview tapes: A-K (no. 1-18) p. 47 BOX 3B. Interview tapes: L-Z (no. 19-34) p. 49 INDEX p. 50 1 THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE INVENTORY BOX 1. Folder titles in bold. Abercrombie, Sharon. “Vietnam ritual” Creation spirituality 8/4 (July/Aug. 1992), p. 18-21. (3 copies – 1 complete issue, 2 photocopies). “An account of a memorable occasion of remembering and healing with Robert Bly, Matthew Fox and Michael Mead”—Contents page. Abrams, Arnold. “Feeling the pain : hands reach out to the vets’ names and offer remembrances” Newsday (Nov. 9, 1984), part II, p. 2-3. (photocopy) Acai, Steve. (Raleigh, NC and North Carolina Vietnam Veterans Memorial Committee) (see also Interview tapes Box 3A Tape 1) Correspondence with LF (ALS and TLS), photos, copies of articles concerning the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the visit of the Moving Wall to North Carolina and the development of the NC VVM. Also includes some family news (Lydia Fish’s mother was resident in NC). (ca. 50 items, 1986-1991) Allen, Christine Hope. “Public celebrations and private grieving : the public healing process after death” [paper read at the American Studies Assn. meeting Nov. 4, 1983] (17 leaves, photocopy) Allen, Henry (see folder titled: Vietnam Veterans Memorial articles) Allen, Jane Addams (see folder titled: The statue) Allen, Leslie. -

The National Vietnam Veterans Memorial's Influence on Two Northern Florida Veterans Memorials Jessamyn Daniel Boyd

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Lasting Resonance: The National Vietnam Veterans Memorial's Influence on Two Northern Florida Veterans Memorials Jessamyn Daniel Boyd Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES LASTING RESONANCE: THE NATIONAL VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL’S INFLUENCE ON TWO NORTHERN FLORIDA VETERANS MEMORIALS By Jessamyn Daniel Boyd A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Jessamyn Daniel Boyd’s defended on March 26, 2007. ______________________ Jen Koslow Professor Direction Thesis ______________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member ______________________ James P. Jones Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Over the course of writing this thesis, I have become indebted to a few people, who provided their help, guidance, and support to make this possible. I have been fortunate to have a wonderful committee that willfully guided me through this writing process. Professor Koslow offered her time to help me sound off ideas, and her assistance to help me when I thought I would not be able to find certain records. Dr. Creswell also aided me in researching this project. His knowledge on the time period and generous editorial assistance was much appreciated. These two professors provided valuable insight and much appreciated support. Dr. -

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Washington, Dc

A NATIONAL SHRINE TO SCAPEGOATING? THE VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL WASHINGTON, D.C. Jon Pahl Valparaiso University In a recent survey I conducted of visitors to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C, 92 percent agreed that "the memorial is a sacred place, and should be treated as such."1 Clearly, this place, by some reports the most visited site in the U.S. capital, draws devotion. But how does a pilgrimage to this memorial function?2 Does pilgrimage to "the wall" serve to "heal a nation," as its builders intended, or does pilgrimage to the memorial ironically legitimize structures of violence like those which led the United States into the Vietnamese conflict in the first place?3 My argument builds upon the work of René Girard to suggest that pilgrimage to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial can legitimize the violence of American culture by 1'The survey was of 185 pilgrims attending ceremonies during Veterans Day, November 11, 1993 and 1994. Several recent works explore the interface between civil religion and violence, notably John E. Bodnar, Karal Ann Marling, and Edward T. Linenthal. On sacred places, the pioneering work of Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane, remains important but must be supplemented by Jonathan Z. Smith's Imagining Religion. 2 Victor and Edith Turner argue cogently that "if a tourist is half pilgrim, a pilgrim is half tourist" (20). Many visitors to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial understand themselves only as tourists, but their behavior appears to me to warrant treatment under the category of "pilgrimage." 3 I assume a "maximalist" definition of violence, which understands the word to refer not only to physical harm to individuals, but also to systemic, social structures of exclusion (such as racism), and ideological (or symbolic) justifications of violence (see Robert McAfee Brown; for a minimalist approach, see Gerald Runkle). -

Memorial to Martin Luther King, Jr.; and Center for Vietnam Veterans Memorial

S. HRG. 108–65 MEMORIAL TO HONOR ARMED FORCES; REQUIREMENTS FOR NAME ON VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL; MEMORIAL TO MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.; AND CENTER FOR VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON S. 268 S. 470 S. 296 S. 1076 JUNE 3, 2003 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 88–261 PDF WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-SEP-98 13:39 Jul 22, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 J:\DOCS\88-261 SENERGY3 PsN: SENERGY3 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico, Chairman DON NICKLES, Oklahoma JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BOB GRAHAM, Florida LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee RON WYDEN, Oregon LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota JAMES M. TALENT, Missouri MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana CONRAD BURNS, Montana EVAN BAYH, Indiana GORDON SMITH, Oregon DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JIM BUNNING, Kentucky CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York JON KYL, Arizona MARIA CANTWELL, Washington ALEX FLINT, Staff Director JAMES P. BEIRNE, Chief Counsel ROBERT M. SIMON, Democratic Staff Director SAM E. FOWLER, Democratic Chief Counsel SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming, Chairman DON NICKLES, Oklahoma, Vice Chairman BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado DANIEL K. -

Remembering Vietnam Overview Students Will Gain a Basic Understanding of the Vietnam War with a Special Focus on the Vietnam Memorial Wall

Remembering Vietnam Overview Students will gain a basic understanding of the Vietnam War with a special focus on the Vietnam Memorial Wall. After assessing student prior knowledge of the Vietnam War using a word web, students examine basic information about the Vietnam War through a jigsaw reading. An illustrated timeline activity and discussion are used to assess student learning of reading. Students learn about the controversy surrounding the creation of the Vietnam Memorial Wall through a “Reader’s Theatre” activity. The lesson culminates with students creating their own Vietnam Memorial for a class competition. Grade High School Materials • Interactive Vietnam Wall Website - http://thewall-usa.com/Panoramas/TheWall.htm o If internet is not available, use the attached image of the Vietnam War Memorial • Vietnam Memorial Wall Image (optional) (attached) o http://ianpatrick.co.nz/gallery/d/2490-2/139+vietnam+war+memorial+wall.jpg • Chart paper and Post-it notes • “A Short Summary of the Vietnam War” handout (attached) • “A Short Summary of the Vietnam War” Questions (attached) • “Short Summary of the Vietnam War” Answer Key (attached) • “Vietnam War Illustrated Timeline” handout (attached) • “The Vietnam Memorial’s History” Script (attached). It is divided into the following “Acts”: o Act I: Prologue o Act IV: The Best o Act VI: A Communist o Act II: Two Officers and Goddamn Among Us Grunt Competition o Act VII: The o Act III: How Much are o Act V: We Had a Compromise You Fellows Putting In? Problem Here o Act VIII: The Soldiers Like -

Annual Report 1 Annualvietnam2010 Veterans Reportmemorial Fund

AnnualVietnam2010 Veterans mReportemorial Fund Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund 2010 Annual Report 1 AnnualVietnam2010 Veterans Reportmemorial Fund our mission To preserve the legacy of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, to promote healing and to educate about the impact of the Vietnam War Dear Friends: Picture the Vietnam Veterans Memorial with its row after row of names. Now imagine, instead of names, there are photos of the thousands of men and women who died or remain missing as a result of the Vietnam War. And think how moving it would be to be able to learn more about the lives of those individuals. Soon, you won’t have to imagine. When the Education Center at The Wall is completed, it will dis- play pictures of the more than 58,000 who died during the Vietnam War. It will tell their stories and share remembrances from family and friends. It will, in short, help us remember those we lost—not just as names on The Wall, but as people full of hopes and dreams and promise, whose lives were cut tragically short. In 2010, VVMF began looking at all we do with an eye toward telling the stories of the people whose names are on The Wall. In our events at The Wall, we recall the people who did not come home from the war and how they touched our lives. This was especially poignant on Father’s Day, Warren Kahle Warren when we helped Sons and Daughters in Touch commemorate its 20th anniversary, and hundreds of SDIT members came to The Wall to remember the fathers they lost in Vietnam. -

![National Salute to Vietnam Veterans] Box: 51](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1684/national-salute-to-vietnam-veterans-box-51-5381684.webp)

National Salute to Vietnam Veterans] Box: 51

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Blackwell, Morton: Files Folder Title: [National Salute to Vietnam Veterans] Box: 51 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ rJU[ 2 9 1882 THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON July 28, 1982 MEMORANDUM FOR ELIZABETH DOL~ FROM: Jim Ciccon~ SUBJECT: National Salute to Vietnam Veterans Attached is material forwarded by Jan Scruggs concerning the National Salute to Vietnam Veterans. Please note that a letter has been sent to the President asking that he and the First Lady serve as Honorary Chairmen. Thanks. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON August 3, 1982 MEMORANDUM FOR MICHAEL K. DEAVER~ FROM: ELIZABETH H. DOLE SUBJECT: National Salute to Vietnam Veterans Attached is a letter inviting President and Mrs. Reagan to serve as the Co-Chairmen of the "National Salute to Vietnam Veterans" that will take place from November 10th to 14th, 1982. I recommend that President and Mrs. Reagan accept this invitation. By accepting this honor, the President and Mrs. Reagan will affirm their appreciation and respect for the thousands of Americans who sacrificed so much for the United States in the Vietnam conflict. I would also like to point out that Mrs. Reagan presently serves on the National Sponsoring Committee for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. Thank you for considering this request. -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Complete the Mission OUR MISSION To preserve the legacy of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, to promote healing, and to educate about the impact of the Vietnam War VVMF ACHIEVES HIGH CHARITY RATINGS VVMF has been recently distinguished with honors from: 1. Great NonProfits, a nonprofit consumer review organization, gave VVMF a 5/5 rating judged on unanimous assessments by its volunteers and contributors. 2. VVMF’s financials, transparency, and program impacts earned 4/4 stars from Charity Navigator and the GuideStar Exchange Seal of Approval. 3. The Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance awarded VVMF its coveted Accredited Charity Seal of Approval based on a 20-point review of its effectiveness in doing business in a fair manner. THE GENESIS OF A LARGER LEGACY OF SERVICE It’s incredibly hard to grasp that 30 years have passed since The entering the final laps of the Wall was completed and dedicated to our Vietnam veterans and race. On November 28 2012, we their families in 1982. And while not a day goes by that I am not conducted a groundbreaking for grateful for the many supporters, political leaders, and donors the Education Center. Speakers who made The Wall a reality — and we have much to be proud included the Secretaries of of — the mission is not yet complete. Defense and Interior, Senator Reed, Congressman Guthrie, We are losing Vietnam veterans at an alarming rate. Each day and Jill Biden. The entire we lose about 417 to illness and age. Their stories are in danger leadership of the U.S. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

112th Congress, 1st Session House Document 112-33 P R O C E E D I N G S of the 111TH ANNUAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Indianapolis, Indiana August 21-26, 2010 June 9, 2011.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2011 66–796 I U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the Ameri- can Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House docu- ments of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] II LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI May, 2011 Honorable John Boehner The Speaker U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Mr. Speaker: In conformance with the provisions of Public Law No. 620, 90th Congress, approved October 22, 1968, I am transmitting to you herewith the proceedings of the 111th National Convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, held in Indianapolis, Indiana, August 21-26, 2010, which is submitted for printing as a House document. -

Vietnam: Echoes from the Wall. History, Learning and Leadership Through the Lens of the Vietnam War Era

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 451 090 SO 032 392 AUTHOR Pearson, Patricia; Percoco, James; Sossaman, Stephen; Wilson, Rob TITLE Vietnam: Echoes from the Wall. History, Learning and Leadership through the Lens of the Vietnam War Era. Teachers' Guide. INSTITUTION Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 162p.; Compiled by Rima Shaffer. Project Underwriters include WinStar Communications, Inc., CNN, Turner Learning, The Kimsey Foundation, E*Trade Group, Inc., and Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States. National Sponsors include Association of the U.S. Army, McCormick Tribune Foundation, Merrill Lynch and Co. Foundation, Inc., Pepsi Cola Company, The Quaker Oats Company, the New York Times Learning Network, and State Street Corporation. Contributors include Exxon Corporation, Phillips Petroleum Company, Pfizer Inc., Showtime Networks Inc., Sunstrand Corporation, Tenneco Inc., United Technologies, Citigroup Foundation, and USAA. AVAILABLE FROM Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, 1023 15th Street, NW, Second Floor, Washington, DC 20005; Tel: 202-393-0090; Fax: 202-393-0029; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.vvmf.org; Web site: http://www.teachvietnam.org/. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Context; Foreign Countries; High Schools; *History Instruction; Learning Modules; *Political Issues; Primary Sources; Student Research; Teaching Guides; *Thinking Skills; *United States History; Vietnam Veterans; *Vietnam War IDENTIFIERS Historical Research; Team Learning; Vietnam; *Vietnam Veterans Memorial; Vietnam War Literature ABSTRACT Today, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial (The Wall) has moved beyond its role as an international symbol of healing and stands as a living history lesson, but many of today's young people have a limited knowledge of the Vietnam War.