The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Washington, Dc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Kenneth Burke and the Theory of Scapegoating Charles K. Bellinger Words Sometimes Play Important Roles in Human History. I

Kenneth Burke and the Theory of Scapegoating Charles K. Bellinger Words sometimes play important roles in human history. I think, for example, of Martin Luther’s use of the word grace to shatter Medieval Catholicism, or the use of democracy as a rallying cry for the American colonists in their split with England, or Karl Marx’s vision of the proletariat as a class that would end all classes. More recently, freedom has been used as a mantra by those on the political left and the political right. If a president decides to go war, with the argument that freedom will be spread in the Middle East, then we are reminded once again of the power of words in shaping human actions. This is a notion upon which Kenneth Burke placed great stress as he painted a picture of human beings as word-intoxicated, symbol-using agents whose motives ought to be understood logologically, that is, from the perspective of our use and abuse of words. In the following pages, I will argue that there is a key word that has the potential to make a large impact on human life in the future, the word scapegoat. This word is already in common use, of course, but I suggest that it is something akin to a ticking bomb in that it has untapped potential to change the way human beings think and act. This potential has two main aspects: 1) the ambiguity of the word as it is used in various contexts, and 2) the sense in which the word lies on the boundary between human self-consciousness and unself-consciousness. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

Getting Beneath the Surface: Scapegoating and the Systems Approach in a Post-Munro World Introduction the Publication of The

Getting beneath the surface: Scapegoating and the Systems Approach in a post-Munro world Introduction The publication of the Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report (2011) was the culmination of an extensive and expansive consultation process into the current state of child protection practice across the UK. The report focused on the recurrence of serious shortcomings in social work practice and proposed an alternative system-wide shift in perspective to address these entrenched difficulties. Inter-woven throughout the report is concern about the adverse consequences of a pervasive culture of individual blame on professional practice. The report concentrates on the need to address this by reconfiguring the organisational responses to professional errors and shortcomings through the adoption of a ‘systems approach’. Despite the pre-occupation with ‘blame’ within the report there is, surprisingly, at no point an explicit reference to the dynamics and practices of ‘scapegoating’ that are so closely associated with organisational blame cultures. Equally notable is the absence of any recognition of the reasons why the dynamics of individual blame and scapegoating are so difficult to overcome or to ‘resist’. Yet this paper argues that the persistence of scapegoating is a significant impediment to the effective implementation of a systems approach as it risks distorting understanding of what has gone wrong and therefore of how to prevent it in the future. It is hard not to agree wholeheartedly with the good intentions of the developments proposed by Munro, but equally it is imperative that a realistic perspective is retained in relation to the challenges that would be faced in rolling out this new organisational agenda. -

Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration March 30, 2018 9 A.M

Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration March 30, 2018 9 a.m. – 12 p.m. Martin’s West, Baltimore, MD Hosted by Gilchrist Presenting Sponsor: Alban CAT “A Grateful Nation Thanks and Honors You.” WE ARE PROUD TO HONOR THE VIETNAM VETS TODAY A VETERAN OWNED COMPANY Heavy equipment, compact construction equipment, power generation, and micro-grid solutions for the Mid-Atlantic & DC Metro Areas 800-443-9813 | www.albancat.com 2 We Honor Veterans Thank you for joining us at Gilchrist’s inaugural Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration—a day to honor and thank the men and women in our community who served during the Vietnam War. Gilchrist is a nationally recognized nonprofit that provides care and support for people with serious illness through the end of life, through elder medical care, counseling and support, and hospice care. Many of Gilchrist’s hospice patients are veterans and many of them served during the Vietnam era. Gilchrist’s Welcome Home celebration honors the veterans in our care as well as all of the veterans in our community, and coincides with Maryland’s Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day, signed into law by Governor Larry Hogan in 2015. This celebration is one of the many ways Gilchrist recognizes the unique needs of veterans and thanks them for their sacrifice and service to our country. We are proud to honor those who have served in the United States Armed Forces. gilchristcares.org 3 Our Sponsors We are grateful to the following sponsors for their support of this event. Four Star Alban CAT Three Star Jonathan and Jennifer Murray Anonymous Donor Two Star Marietta and Ed Nolley Martin’s West Webb Mason Colonel H. -

Working with People Who Commit Hate Crime RANIA HAMAD (UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH) December 2019 INSIGHT 50 · Working with People Who Commit Hate Crime 2

INSIGHTS 50 A SERIES OF EVIDENCE SUMMARIES Working with people who commit hate crime RANIA HAMAD (UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH) DECEMBER 2019 INSIGHT 50 · WORKing with PEOPLE WHO COMMit HATE CRIME 2 Acknowledgements This Insight was reviewed by Helen Allbutt and Kristi Long (NHS Education for Scotland), Sarah Davis (Community Intervention Team, City of Edinburgh Council), Paul Iganski (Lancaster University), Steve Kirkwood (University of Edinburgh), Maureen McBride (University of Glasgow), Neil Quinn (University of Strathclyde) and colleagues from Scottish Government. Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and comment on this publication. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 2.5 UK: Scotland Licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/ Copyright ©December 2019 INSIGHT 50 · WORKing with PEOPLE WHO COMMit HATE CRIME 3 Key points • Criminal Justice Social Work (CJSW) practitioners work on a daily basis with people convicted of hate crime and/or display prejudice, but there is a lack of specific Scottish research on effective practice in this area. • From the existing research, hate crime interventions are best undertaken one-to-one, incorporating cultural/diversity awareness, anger/emotion management, hate crime impact and restorative justice. • People convicted of hate crime frequently experience adverse circumstances and may have unacknowledged shame, anger, and feelings of threat and loss. • Practitioners should develop relationships with people who commit hate offences characterised by acceptance, respect, and empathy, without judgement or collusion. -

Technology-Enabled Bullying & Adolescent Non-Reporting

Technology-enabled Bullying & Adolescent Non-reporting Breaking the Silence Justin Connolly1 and Regina Connolly2 1Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Dublin, Ireland 2Dublin City University, Business School, Dublin 9, Dublin, Ireland Keywords: Information and Communication Technologies, Technology-enabled Bullying, Cyberbullying. Abstract: Although early research has pointed to the fact that the successful intervention and resolution of cyberbullying incidents is to a large degree dependent on such incidents being reported to an adult caregiver, the literature consistently shows that adolescents who have been bullied tend not to inform others of their experiences. However, the reasons underlying reluctance to seek adult intervention remain undetermined. Understanding the factors that influence adolescent resistance will assist caregivers, teachers and those involved in the formulation of school anti-bullying policies in their attempts to counter the cyberbullying phenomenonre should be a space before of 12-point and after of 30-point. 1 INTRODUCTION harmful behavior. Direct cyberbullying involves repeatedly sending offensive messages. More The problem of adolescent bullying has evolved in indirect forms of cyberbullying include tandem with the digitization of society. Bullying is disseminating denigrating materials or sensitive a problem that transcends social boundaries and can personal information or impersonating someone to result in devastating psychological and emotional cause harm (p.10).’ trauma including low self-esteem, poor academic As can be seen from the above definitions, there performance, depression, and, in some cases, are important distinctions between cyberbullying violence and suicide. In its traditional context, it has and bullying. The first distinction relates to the been described as being characterized by the nature of the bullying. -

A/HRC/46/57 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/46/57 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 March 2021 Original: English Human Rights Council Forty-sixth session 22 February–19 March 2021 Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Minority issues Report of the Special Rapporteur on minority issues, Fernand de Varennes*, ** Summary In the present report, the Special Rapporteur on minority issues, Fernand de Varennes, provides an overview of his activities since his previous report (A/HRC/43/47), and a thematic report in which he addresses the widespread targeting of minorities through hate speech in social media. He describes related phenomena, including the widespread denial or failure of State authorities to recognize or effectively protect minorities against prohibited forms of hate speech. He concludes by emphasizing the responsibility of States, civil society and social media platforms to acknowledge that hate speech is mainly a minority issue and, as a matter of urgency, their duty to take further steps towards the full and effective implementation of the human rights obligations involved. * The present report was submitted after the deadline so as to reflect the most recent information. ** The annexes to the present report are circulated as received, in the language of submission only. GE.21-02920(E) A/HRC/46/57 I. Introduction 1. The mandate of the Special Rapporteur on minority issues was established by the Commission on Human Rights in its resolution 2005/79 of 21 April 2005, and subsequently extended by the Human Rights Council in successive resolutions. -

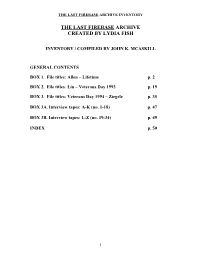

The Last Firebase Archive Created by Lydia Fish

THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE INVENTORY THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE CREATED BY LYDIA FISH INVENTORY / COMPILED BY JOHN K. MCASKILL GENERAL CONTENTS BOX 1. File titles: Allen – Lifetime p. 2 BOX 2. File titles: Lin – Veterans Day 1993 p. 19 BOX 3. File titles: Veterans Day 1994 – Ziegele p. 35 BOX 3A. Interview tapes: A-K (no. 1-18) p. 47 BOX 3B. Interview tapes: L-Z (no. 19-34) p. 49 INDEX p. 50 1 THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE INVENTORY BOX 1. Folder titles in bold. Abercrombie, Sharon. “Vietnam ritual” Creation spirituality 8/4 (July/Aug. 1992), p. 18-21. (3 copies – 1 complete issue, 2 photocopies). “An account of a memorable occasion of remembering and healing with Robert Bly, Matthew Fox and Michael Mead”—Contents page. Abrams, Arnold. “Feeling the pain : hands reach out to the vets’ names and offer remembrances” Newsday (Nov. 9, 1984), part II, p. 2-3. (photocopy) Acai, Steve. (Raleigh, NC and North Carolina Vietnam Veterans Memorial Committee) (see also Interview tapes Box 3A Tape 1) Correspondence with LF (ALS and TLS), photos, copies of articles concerning the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the visit of the Moving Wall to North Carolina and the development of the NC VVM. Also includes some family news (Lydia Fish’s mother was resident in NC). (ca. 50 items, 1986-1991) Allen, Christine Hope. “Public celebrations and private grieving : the public healing process after death” [paper read at the American Studies Assn. meeting Nov. 4, 1983] (17 leaves, photocopy) Allen, Henry (see folder titled: Vietnam Veterans Memorial articles) Allen, Jane Addams (see folder titled: The statue) Allen, Leslie. -

The National Vietnam Veterans Memorial's Influence on Two Northern Florida Veterans Memorials Jessamyn Daniel Boyd

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Lasting Resonance: The National Vietnam Veterans Memorial's Influence on Two Northern Florida Veterans Memorials Jessamyn Daniel Boyd Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES LASTING RESONANCE: THE NATIONAL VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL’S INFLUENCE ON TWO NORTHERN FLORIDA VETERANS MEMORIALS By Jessamyn Daniel Boyd A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Jessamyn Daniel Boyd’s defended on March 26, 2007. ______________________ Jen Koslow Professor Direction Thesis ______________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member ______________________ James P. Jones Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Over the course of writing this thesis, I have become indebted to a few people, who provided their help, guidance, and support to make this possible. I have been fortunate to have a wonderful committee that willfully guided me through this writing process. Professor Koslow offered her time to help me sound off ideas, and her assistance to help me when I thought I would not be able to find certain records. Dr. Creswell also aided me in researching this project. His knowledge on the time period and generous editorial assistance was much appreciated. These two professors provided valuable insight and much appreciated support. Dr. -

Cyber Bulling

Cyberbullying What Can I Do? Mark S. Borer, MD, DFAPA, DFAACAP 5/16 Subset of: Bullying and Social Aggression in DE Medical Society of Delaware 5/16 © All rights reserved Credits for Archived Slide Set • Dr. Borer has presented on bullying at various schools and staff developments over his years in practice and he has created different portions of this slide set over time. The slide set is updated from time to time from online, organizational, and educational resources, as well as from ongoing clinical experience. • Formatting for the slides was provided in part by Medical Society of Delaware. • Some of the slides present materials available through various referenced websites. Dr. Borer also prepared an educational program on bullying and social aggression for Lorman Seminars in ’06, which informs some of his thoughts and topics in this slide set, and which he references herein. • The presentations by Dr. Borer at the Medical Society of Delaware, as well as this slide set, have been shared for the benefit of Delaware’s youth. Dr. Borer has received no remuneration for use of this slide set. The materials in these slides may inform the presentations of others, but the slide set itself is copyrighted and used with permission by the Medical Society of DE and by the Delaware Bullying Prevention Association. Cyberbullying—A Definition • CYBER OR ELECTRONIC Bullying – using the Internet, email, text messaging, or other social media to threaten, harass, hurt, single out, embarrass, spread rumors, and/or reveal secrets about others. • Engaging others in targeting a particular individual enhances the bullying and the potential hurt and damage to the individual. -

(2005) Cyber Bullying: an Old Problem in a New Guise?

1 This is the author’s version of a paper that was later published as: Campbell, Marilyn A (2005) Cyber bullying: An old problem in a new guise?. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling 15(1):68-76. Copyright 2005 Australian Academic Press. Cyber bullying: An old problem in a new guise? Marilyn A. Campbell Queensland University of Technology Abstract Although technology provides numerous benefits to young people, it also has a ’dark side’, as it can be used for harm, not only by some adults but also by the young people themselves. Email, texting, chat rooms, mobile phones, mobile phone cameras and web sites can and are being used by young people to bully peers. It is now a global problem with many incidents reported in the United States, Canada, Japan, Scandinavia and the United Kingdom, as well as in Australia and New Zealand. This growing problem has as yet not received the attention it deserves and remains virtually absent from the research literature. This article explores definitional issues, the incidence and potential consequences of cyber bullying, as well as discussing possible prevention and intervention strategies. 2 Historically bullying has not been seen as a problem that needed attention, but rather has been accepted as a fundamental and normal part of childhood (Limber & Small, 2003). In the last two decades, however, this view has changed and schoolyard bullying is seen as a serious problem that warrants attention. Bullying is an age-old societal problem, beginning in the schoolyard and often progressing to the boardroom (McCarthy, Rylance, Bennett, & Zimmermann, 2001). -

Examining Cyberbullying Bystander Behavior Using a Multiple Goals Perspective

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Communication Communication 2014 Examining Cyberbullying Bystander Behavior Using a Multiple Goals Perspective Sarah E. Jones University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, Sarah E., "Examining Cyberbullying Bystander Behavior Using a Multiple Goals Perspective" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Communication. 22. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/comm_etds/22 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Communication by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies.