The Influence of the Vietnam War in Contemporary Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![RESUME [V6.0].Cwk](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0648/resume-v6-0-cwk-10648.webp)

RESUME [V6.0].Cwk

Robert Charles Doyle 1317 Ridge Avenue Steubenville, Ohio 43952 Phone: (740) 282-8156 [email protected] Education Ph. D Bowling Green State University, American Culture Studies, 1987. M. A. Pennsylvania State University, Comparative Literature, 1976. B. A. Pennsylvania State University, Liberal Arts, German, 1967. Present Academic Employment (2001 - present) Professor, United States History, Department of History, Franciscan University of Steubenville, Steubenville, Ohio, 2007 to the present. Previous Academic Employment (1974 - 2001) Associate Professor, United States History, Department of History, Franciscan University of Steubenville, Steubenville, Ohio, 2001-2007 Instructor, United States History, Department of History, Franciscan University of Steubenville, Steubenville, Ohio, 2000-2001. Professeur and Maître de Conferences (Professor and Visiting Associate Professor), American Civilization, Département d’Etudes Anglaises et Nord-Américaines, Université Strasbourg, France, 1995-1998. Instructor (Part-Time), American Civilization, Department of Foreign Languages, Université Robert Schuman, Strasbourg, France, 1996-1997. Professor (Fulbright), American Studies, Englisches Seminar, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, Münster, Germany, 1994-1995. Lecturer, American Studies, Department of English, Penn State University, University Park, 1988-1994. Lecturer (Part-Time), American Studies, Division of Continuing Education, Penn State University, University Park and Abington Campus, 1987-1988. Graduate Fellow (Teaching, 1984-86; Non-Service, 1986-1987), American Culture Doctoral Program, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio, 1984-1987. Lecturer (Part-Time), American Studies, Division of Continuing Education, Penn State University, University Park, 1974-1977. Technical Adviser/Consultant Historical and Technical Advisor. Hart’s War. Dir. Gregory Hoblit, with Bruce Willis. MGM/UA (Warhart Productions), 2000-2001. Historical and Applied Research Consultant, Joint Personnel Recovery Agency (USAF), Ft. Belvoir, Virginia, 1998-2000. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

Apocalypse Now, Vietnam and the Rhetoric of Influence Autor(Es): Childs, Jeffrey Publicado Por: Centro De Literatura Portuguesa

Apocalypse now, Vietnam and the rhetoric of influence Autor(es): Childs, Jeffrey Publicado por: Centro de Literatura Portuguesa URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/30048 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/2182-8830_1-2_1 Accessed : 30-Sep-2021 22:18:52 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Apocalypse Now, Vietnam and the Rhetoric of Influence JEFFREY CHILDS Universidade Aberta | Centro de Estudos Comparatistas, Univ. de Lisboa Abstract Readings of Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979) often confront the difficulty of having to privilege either its aesthetic context (considering, for instance, its relation to Conrad's Heart of Darkness [1899] or to the history of cinema) or its value as a representation of the Vietnam War. -

Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration March 30, 2018 9 A.M

Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration March 30, 2018 9 a.m. – 12 p.m. Martin’s West, Baltimore, MD Hosted by Gilchrist Presenting Sponsor: Alban CAT “A Grateful Nation Thanks and Honors You.” WE ARE PROUD TO HONOR THE VIETNAM VETS TODAY A VETERAN OWNED COMPANY Heavy equipment, compact construction equipment, power generation, and micro-grid solutions for the Mid-Atlantic & DC Metro Areas 800-443-9813 | www.albancat.com 2 We Honor Veterans Thank you for joining us at Gilchrist’s inaugural Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day Celebration—a day to honor and thank the men and women in our community who served during the Vietnam War. Gilchrist is a nationally recognized nonprofit that provides care and support for people with serious illness through the end of life, through elder medical care, counseling and support, and hospice care. Many of Gilchrist’s hospice patients are veterans and many of them served during the Vietnam era. Gilchrist’s Welcome Home celebration honors the veterans in our care as well as all of the veterans in our community, and coincides with Maryland’s Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day, signed into law by Governor Larry Hogan in 2015. This celebration is one of the many ways Gilchrist recognizes the unique needs of veterans and thanks them for their sacrifice and service to our country. We are proud to honor those who have served in the United States Armed Forces. gilchristcares.org 3 Our Sponsors We are grateful to the following sponsors for their support of this event. Four Star Alban CAT Three Star Jonathan and Jennifer Murray Anonymous Donor Two Star Marietta and Ed Nolley Martin’s West Webb Mason Colonel H. -

Minding the Gap Addressing Civilian Misconduct in Deployed Environments by Reviving Article 2, Uniform Code of Military Justice

Minding the Gap Addressing Civilian Misconduct in Deployed Environments by Reviving Article 2, Uniform Code of Military Justice By Erin Lai B.A., December 2000, University of California, Los Angeles J.D., May 2004, University of California, Los Angeles School of Law A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The George Washington University Law School in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws August 31, 2013 Thesis directed by Charles B. Craver Freda H. Alverson Professor of Law Acknowledgments The author wishes to thank Professor Charles Craver for his steadying influence whenever panic set in; her husband, Kent H. Wheeler, who willingly and effortlessly played the role of Superdad to crazy daughter, Zora, so that she could focus on school, and without whose love and patience this thesis would not have happened; her parents and in-laws, whose support and encouragement meant more than they‘ll ever know; Lt Col J‘oel Santa Teresa, whose mentorship over the years helped make this possible, and last, but not least, Lt Col Joshua Kastenberg, who tirelessly served as a sounding board for the woes of the thesis writing process and whose guidance and friendship has been invaluable. ii Disclaimer Major Erin Lai serves in the U.S. Air Force Judge Advocate General‘s Corps. This paper was submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws in Labor and Employment Law at The George Washington University Law School. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense or U.S. -

VIETNAM VETERAN THEATRICAL NARRATIVES by Amanda Boyle Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program In

MEN, MEMORY, AND MEMORIAL: VIETNAM VETERAN THEATRICAL NARRATIVES By Amanda Boyle Submitted to the graduate degree program in Theatre and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Henry Bial ________________________________ Jane Barnette ________________________________ Rebecca Rovit ________________________________ Nicole Hodges Persley ________________________________ Adrian Lewis Date Defended: May 9, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Amanda Boyle certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: MEN, MEMORY, AND MEMORIAL: VIETNAM VETERAN THEATRICAL NARRATIVES ________________________________ Chairperson Henry Bial Date approved: May 12, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation is a study of Vietnam War veteran narratives and how they are presented on stage. I argue that these plays are a form of commemoration of the Vietnam War and those who fought in it. I eXamine three plays: Medal of Honor Rag (1976) by Tom Cole, Still Life (1982) by Emily Mann, and Tracers (1983) by John DiFusco, et al. There are hundreds of plays and musicals written directly about the war. Through a dramaturgical methodology I combine teXtual analysis, production research, interviews with two of the three playwrights, academic scholarship on the plays, my own staged reading of Still Life in February 2015, and select oral/written histories from Vietnam veterans to illustrate how the plays function as commemorative-storytelling of the veteran experience. Each chapter is a dramaturgical case study that could be used for production. The plays each have a wide range of topics, motifs, and themes, many of which I address, including the overlapping themes of wounding (moments of injury and psychological repercussions), coming home (surviving the war and returning home), and commemorating (via medals and memorials). -

WPS Handbook 2013-14

POSTGRADUATE MODULE HANDBOOK Department of Politics, Birkbeck, University of London WAR, POLITICS AND SOCIETY Dr Antoine Bousquet [email protected] Introduction Module Aims and Objectives War, Politics and Society aims to provide students with an advanced understanding of the role of war in the modern world. Drawing on a wide range of social sciences and historiographical sources, its focus will be on the complex interplay between national, international and global political and social relations and the theories and practices of warfare since the inception of the modern era and the ‘military revolution’ of the sixteenth century. The module will notably examine the role of war in the emergence and development of the nation-state, the industrialisation and modernisation of societies and their uses of science and technology, changing cultural attitudes to the use of armed force and martial values, and the shaping of historical consciousness and collective memory. Among the contemporary issues addressed are the ‘war on terror’, weapons of mass destruction, genocide, humanitarian intervention, and war in the global South. Students completing the module will: • be able to evaluate and critically apply the central literatures, concepts, theories and methods used in the study of the relations between war, politics and society; • demonstrate balanced, substantive knowledge of the central debates within war studies; • be capable of historically informed, critical analysis of current political and strategic debates concerning the use of armed force; • be able to obtain and analyse relevant information on armed forces and armed conflict from a wide array of governmental, non-governmental, military and media sources; • have developed transferable skills, including critical evaluation, analytical investigation, written and oral presentation and communication. -

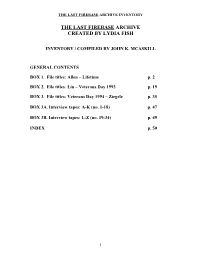

The Last Firebase Archive Created by Lydia Fish

THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE INVENTORY THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE CREATED BY LYDIA FISH INVENTORY / COMPILED BY JOHN K. MCASKILL GENERAL CONTENTS BOX 1. File titles: Allen – Lifetime p. 2 BOX 2. File titles: Lin – Veterans Day 1993 p. 19 BOX 3. File titles: Veterans Day 1994 – Ziegele p. 35 BOX 3A. Interview tapes: A-K (no. 1-18) p. 47 BOX 3B. Interview tapes: L-Z (no. 19-34) p. 49 INDEX p. 50 1 THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE INVENTORY BOX 1. Folder titles in bold. Abercrombie, Sharon. “Vietnam ritual” Creation spirituality 8/4 (July/Aug. 1992), p. 18-21. (3 copies – 1 complete issue, 2 photocopies). “An account of a memorable occasion of remembering and healing with Robert Bly, Matthew Fox and Michael Mead”—Contents page. Abrams, Arnold. “Feeling the pain : hands reach out to the vets’ names and offer remembrances” Newsday (Nov. 9, 1984), part II, p. 2-3. (photocopy) Acai, Steve. (Raleigh, NC and North Carolina Vietnam Veterans Memorial Committee) (see also Interview tapes Box 3A Tape 1) Correspondence with LF (ALS and TLS), photos, copies of articles concerning the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the visit of the Moving Wall to North Carolina and the development of the NC VVM. Also includes some family news (Lydia Fish’s mother was resident in NC). (ca. 50 items, 1986-1991) Allen, Christine Hope. “Public celebrations and private grieving : the public healing process after death” [paper read at the American Studies Assn. meeting Nov. 4, 1983] (17 leaves, photocopy) Allen, Henry (see folder titled: Vietnam Veterans Memorial articles) Allen, Jane Addams (see folder titled: The statue) Allen, Leslie. -

The National Vietnam Veterans Memorial's Influence on Two Northern Florida Veterans Memorials Jessamyn Daniel Boyd

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Lasting Resonance: The National Vietnam Veterans Memorial's Influence on Two Northern Florida Veterans Memorials Jessamyn Daniel Boyd Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES LASTING RESONANCE: THE NATIONAL VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL’S INFLUENCE ON TWO NORTHERN FLORIDA VETERANS MEMORIALS By Jessamyn Daniel Boyd A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Jessamyn Daniel Boyd’s defended on March 26, 2007. ______________________ Jen Koslow Professor Direction Thesis ______________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member ______________________ James P. Jones Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Over the course of writing this thesis, I have become indebted to a few people, who provided their help, guidance, and support to make this possible. I have been fortunate to have a wonderful committee that willfully guided me through this writing process. Professor Koslow offered her time to help me sound off ideas, and her assistance to help me when I thought I would not be able to find certain records. Dr. Creswell also aided me in researching this project. His knowledge on the time period and generous editorial assistance was much appreciated. These two professors provided valuable insight and much appreciated support. Dr. -

Special Programming on the Vietnam War and the 40 Anniversary of the Fall of Saigon to Air on CPTV This April

For Immediate Release Contact: Carol Sisco [email protected] (860) 275-7212 cpbn.org, cptv.org, wnpr.org Special Programming on the Vietnam War and the 40th Anniversary of the Fall of Saigon to Air on CPTV This April • My Lai: American Experience airs on Tuesday, April 21 at 9 p.m. • The Draft premieres Monday, April 27 at 9 p.m., followed by Dick Cavett’s Vietnam at 10 p.m. • The Day the 60s Died premieres Tuesday, April 28 at 8 p.m., followed by Last Days in Vietnam: American Experience at 9 p.m. and Lost Child: Sayon’s Journey at 11 p.m. HARTFORD, Conn. (April 3, 2015) – CPTV/Connecticut Public Television will present special programming in April focusing on the fall of Saigon and the Vietnam War. The programming begins with an encore airing of My Lai: American Experience on Tuesday, April 21 at 9 p.m. This film focuses on the 1968 My Lai massacre – known as one of the worst atrocities in American military history – and its subsequent cover-up, as well as the heroic efforts of the soldiers who broke ranks to try to halt the massacre and bring it to light. Other programs airing in April include The Draft, premiering Monday, April 27 at 9 p.m., exploring the history of the selective service system in America; and Dick Cavett’s Vietnam, premiering April 27 at 10 p.m., featuring a look back at conversations the talk show host had about the war with a number of public figures. Additional programming includes The Day the 60s Died, airing Tuesday, April 28 at 8 p.m., preceding the premiere of Last Days in Vietnam: American Experience at 9 p.m. -

Journey to the Academy Awards: an Investigation of Oscar-Shortlisted and Nominated Documentaries (2014-2016)

Journey to the Academy Awards: An Investigation of Oscar-Shortlisted and Nominated Documentaries (2014-2016) PRELIMINARY KEY FINDINGS By Caty Borum Chattoo, Co-Director, Center for Media & Social Impact American University School of Communication | Washington, D.C. February 2016 OVERVIEW For a documentary filmmaker, being recognized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences for an Oscar nomination in the Best Documentary Feature category is often the pinnacle moment in a career. Beyond the celebratory achievement, the acknowledgment can open up doors for funding and opportunities for next films and career opportunities. The formal recognition happens in three phases: It begins in December with the Academy’s announcement of a shortlist—15 films that advance to a formal nomination for the Academy’s Best Documentary Feature Award. Then, in mid-January, the final list of five official nominations is announced. Finally, at the end of February each year, the one winner is announced at the Academy Awards ceremony. Beyond a film’s narrative and technical prowess, the marketing campaigns that help a documentary make it to the shortlist and then the final nomination list are increasingly expensive and insular, from advertisements in entertainment trade outlets to lavish events to build buzz among Academy members and industry influencers. What does it take for a documentary film and its director and producer to make it to the top—the Oscars shortlist, the nomination and the win? Which film directors are recognized—in terms of race and gender? -

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE “The Great War” Premieres Monday-Wednesday, April 10-12, 2017

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE “The Great War” Premieres Monday-Wednesday, April 10-12, 2017 Three-Part Series Explores How World War I Forever Changed America and the World (BOSTON, MA) — Scheduled in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of America’s entry into the war on April 6, 1917, AMERICAN EXPERIENCE “The Great War,” a three-part, six-hour documentary, will premiere Monday, April 10, through Wednesday, April 12, 9:00-11:00 p.m. ET (check local listings) on PBS. Featuring the voices of Campbell Scott, Blythe Danner, Courtney Vance and others, “The Great War” is executive produced by Mark Samels and directed by award-winning filmmakers Stephen Ives, Amanda Pollak and Rob Rapley. Drawing on the latest scholarship, including unpublished diaries, memoirs and letters, “The Great War” tells the rich and complex story of World War I through the voices of nurses, journalists, aviators and the American troops who came to be known as “doughboys.” The series explores the experiences of African- American and Latino soldiers, suffragists, Native-American “code talkers” and others whose participation in the war to “make the world safe for democracy” has been largely forgotten. “The Great War” also explores how a brilliant PR man bolstered support for the war in a country hesitant to put lives on the line for a foreign conflict; how President Woodrow Wilson steered the nation through almost three years of neutrality, only to reluctantly lead America into the bloodiest conflict the world had ever seen, thereby transforming the United States into a dominant player on the international stage; and how the ardent patriotism and determination to support America’s crusade for liberty abroad led to one of the most oppressive crackdowns on civil liberties at home in American history.