Contribution by the United Nations Secretariat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Heating Oil Tanks – a Hidden Threat?

Home Heating Oil Tanks – A Hidden Threat? For many homeowners, especially those that own shorefront property, your heating oil storage tank may be the greatest risk of financial liability to which you will ever be exposed. If you are uncomfortable exposing your self to possibly hundreds of thousands of dollars of clean up costs, permanent property devaluation and legacy liens on your property, please read on. Homes have been heated with #2 heating oil and kerosene for many generations. Both fuels have proven to be safe and reliable forms of home heating energy. Compared to natural gas, propane, electric, and solid fuel - oil and kerosene carry an added risk to the homeowner - the chance of a release of federally designated Haz-Mat material which, exceeding a total release of 10 gallons, requires an extensive and expensive clean up to protect both the environment and its inhabitants from lasting negative effects. For this discussion we will look at heating tanks in three separate categories – (1) standard home heating oil tanks, usually 275 gallons and located in the cellar, (2) underground oil tanks ranging in size from 275 gallons to 1000 gallons and (3) above ground oil tanks located outside or in garages or other outbuildings. Standard cellar oil tanks Many homes have a 275-gallon oil tank located in the cellar with a fill and vent pipe terminating to the outside of the home. Current code requires that the fill pipe be equipped with an industry approved fill cap that allows your heating oil supplier to couple their delivery hose to the tank, leak free. -

Matthew Huber

Journal of American Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/AMS Additional services for Journal of American Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Refined Politics: Petroleum Products, Neoliberalism, and the Ecology of Entrepreneurial Life MATTHEW HUBER Journal of American Studies / Volume 46 / Special Issue 02 / May 2012, pp 295 312 DOI: 10.1017/S0021875812000126, Published online: 30 May 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0021875812000126 How to cite this article: MATTHEW HUBER (2012). Refined Politics: Petroleum Products, Neoliberalism, and the Ecology of Entrepreneurial Life. Journal of American Studies, 46, pp 295312 doi:10.1017/S0021875812000126 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AMS, IP address: 92.28.162.159 on 07 Jan 2013 Journal of American Studies, (), , – © Cambridge University Press doi:./S Refined Politics: Petroleum Products, Neoliberalism, and the Ecology of Entrepreneurial Life MATTHEW HUBER Oil is often thought of as a sole commodity with singular powers to shape geopolitics, economic development, and environmental change. Yet the complex hydrocarbon assemblage of crude oil is only commodified through the refining process, which produces a multiplicity of products (e.g. gasoline, heating oil, petrochemicals). In this paper, I argue that petroleum products provide the supplementary materiality for a neoliberal cultural politics of “life.” In the first section, drawing from Gramsci and Foucault, I argue that the popular basis of neoliberal hegemony is rooted in a cultural politics of “entrepreneurial life” that accompanied increasing suburbaniza- tion, single-family homeownership and widespread automobility in the post-World War II United States. -

Biodiesel Blending in Home Heating Oil a Smart Choice for New York

Biodiesel Blending in Home Heating Oil A Smart Choice for New York A Policy Paper New York Public Interest Research Group Fund June, 2014 Acknowledgements This report was written by Joseph Stelling of the New York Public Interest Research Group Fund. The author thanks Executive Director Rebecca Weber, Legislative Director Blair Horner, and Special Projects Director Diana Fryda for their significant contributions to this report. The New York Public Interest Research Group Fund (NYPIRG) is a non-partisan, not-for-profit organization working to cultivate a broad, solution-centered understanding of critical matters affecting the environment, health, democratic institutions and quality of life among New York State’s residents. NYPIRG’s unique approach to public engagement relies upon a solid foundation of research, data analysis, published reports and earned media alongside a rooted, organized presence in communities across New York State earned through decades of face-to- face community outreach, activist recruitment, advocacy training, coalition work, event organizing and voter empowerment. ©2014, NYPIRG You can download the report by going to the NYPIRG website: www.nypirg.org Blending Biodiesel in Home Heating Oil: A Smart Choice for New York Executive Summary This report explores the potential benefits of blending biodiesel into heating oil for New York State. The findings of this report indicate that standardized blending of modest amounts of biodiesel into home heating oil across New York would result in substantial environmental, public health, consumer and economic benefits. Key Findings: 1) Biodiesel blending in heating oil offers reductions in harmful emissions such as particulate matter, sulfates and air toxics, significant lifecycle reductions in climate- altering carbon emissions, and increased sustainability in energy practices. -

A Historical Geography of Natural Gas and the Capitalist State in an Age of Climate Change

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE December 2018 Gaseous State: A Historical Geography of Natural Gas and the Capitalist State in an Age of Climate Change Carlo Sica Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sica, Carlo, "Gaseous State: A Historical Geography of Natural Gas and the Capitalist State in an Age of Climate Change" (2018). Dissertations - ALL. 956. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/956 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract In the 1930s U.S., a set of social forces and crises pushed forward state energy regulation. As states struggle to end greenhouse-gas emissions from fossil fuels, the threat of climate change demands new explanations for how energy policy emerges. In this dissertation, I explain the period of U.S. natural gas regulation between 1938 and 1978 from critical political economy and Marxist state theoretical perspectives. My main conclusion is that the capitalist state stabilizes markets for energy to serve capital with an auxiliary means of production. Based on that conclusion, I recommend that Marxist state theory be class-centered, i.e., recognize that the agency of mass movements and state workers to reform the capitalist state is structurally constrained by the state’s role of maintaining capitalist class relations. In the introduction I explain how it is important to consider capital-gas relations because natural gas is a greenhouse gas and burning of gas by capital is causing climate change. -

Making Your Own Fuel from Vegetable Oil Can Be Easy, Cost- Effective, And

Joshua & Kaia Tickell ©1999 Joshua & Kaia Tickell Restaurant fryer filters are available at restaurant supply stores and are excellent for filtering food particles out of used cooking oil. aking your own fuel from Grow Your Fuel We produce a large quantity of used vegetable oil in the vegetable oil can be easy, cost- United States, but there is an oilseed crop you can effective, and environmentally grow no matter where you live. The possibilities include M coconut, soybean, canola (rapeseed), sunflower, beneficial. What makes this fuel even safflower, corn, palm kernel, peanut, jatropha, and more attractive is that you can make it hundreds more. To learn which vegetable oil crop is best suited for your area, contact your state’s office of from the waste vegetable oil produced agriculture, the agriculture department of a local in the United States every year, which university, or talk to local farmers. amounts to more than three billion One of the crops with the highest yield of oil per acre is gallons. With a bit of know-how and canola. From just one acre of canola, you can produce 100 gallons (379 l) of vegetable oil. The most common persistence, you can run any diesel oilseed crop in the U.S. is soybeans, which produce 50 engine on vegetable oil. gallons (189 l) of vegetable oil per acre. Growing your own oilseed crop has an added bonus. Only diesel engines can run on vegetable oil-based The meal that is separated from the oil is an excellent fuels. This means that any engine that has spark plugs source of protein. -

What Is Bioheat?

What is Bioheat? 1) Is Bioheat the same as biodiesel, or visa versa? NO. Biodiesel is the term for the pure biodiesel, B100. Bioheat is conventional heating oil containing biodiesel. 2) What is biodiesel? Biodiesel is a clean burning alternative fuel produced from vegetable oils and animal fats through a chemical reaction and meeting ASTM D 6751. Biodiesel contains no petroleum, but it can be blended at any level with heating oil. It can be used in home heating oil systems safely with no modifications to the fuel tanks, pumps or burners in concentrations up to 20% biodiesel with only minimal precautions (see conditions for use section). For higher Bioheat blends than 20% biodiesel, special precautions are needed (see materials compatibility). Pure biodiesel is also referred to as B100. In the transportation fuel market where ASTM D 975 is the standard for petroleum-based diesel, biodiesel blends are designated "BXX", where XX is the volume percent of biodiesel meeting ASTM D 6751 with conventional petrodiesel. B20, which is 20% biodiesel and 80% petrodiesel, is a common blend for fleets and buses. The heating oil market is focusing on Bioheat, which is a 2 to 20% blend of biodiesel with heating oil. 3) Is biodiesel the same thing as raw vegetable oil, cooking oil or animal fat? Can those materials be blended with heating oil to create Bioheat? NO. Biodiesel is produced from raw vegetable oils or animal fats, but the oil or fat must go through the chemical reaction (called transesterification) to make it into biodiesel and be tested to make sure it meets D 6751 before it is blended with heating oil. -

Switching from Dirty #4 Or #6 Heating Oil to Cleaner Fuel

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: SWITCHING FROM DIRTY #4 OR #6 HEATING OIL TO CLEANER FUEL ConEdison (if you live in Manhattan, Bronx or northern Queens) at 1-800-643-1289 or More than 9,000 big buildings in New York National Grid still burn the lowest (if you live in Brooklyn, Staten Island or possible grade heating southern Queens) oil. at 1-877-696-4743 Soot from a building burning No. 6 oil Burning dirty heating oil pollutes the air with Why should my building switch to What is required to convert to cleaner nickel, a heavy metal cleaner heating fuel? fuel? that increases the risk of It protects your health. Burning dirty heating oil heart disease. • Contact ConEdison (if you live in (#4 and #6 oil) emits high levels of fine sooty Manhattan, Bronx or northern Queens) at particle pollution and nickel (a heavy metal), 1-800-643-1289 or National Grid (if you live in which are both harmful to our health. Brooklyn, Staten Island or southern Queens) at Using a higher-grade oil 1-877-696-4743 to find out a) if your utility or natural gas reduces It can save you money. Converting to natural company can bring a gas line to your building; soot pollution emissions gas and increasing heating system efficiency b) if your utility company will pay to bring the can help buildings save money. Natural gas is by 95 percent. line to your building; c) if your building is located cheaper than heating oil and the more efficiently in a low or high gas pressure area; and d) about the heating system is running, the less fuel a the different gas rates (firm or interruptible). -

Bioheat Questions & Answers

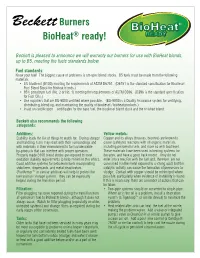

Burners ® Beckett BioHeat BioHeat® ready! READY Beckett is pleased to announce we will warranty our burners for use with BioHeat blends, up to B5, meeting the fuels standards below. Fuel standards: Know your fuel! The biggest cause of problems is off-spec blend stocks. B5 fuels must be made from the following materials: • 5% biodiesel (B100) meeting the requirements of ASTM D6751. (D6751 is the standard specification for Biodiesel Fuel Blend Stock for Bioheat blends.) • 95% petroleum fuel (No. 2 or No. 1) meeting the requirements of ASTM D396. (D396 is the standard specification for Fuel Oils.) • Use suppliers that are BQ-9000 certified where possible. (BQ-9000 is a Quality Assurance system for certifying, distributing, blending, and maintaining the quality of biodiesel / bioheat products.) • Insist on certification – certificates for the base fuel, the biodiesel blend stock and the finished blend. Beckett also recommends the following safeguards: Additives: Yellow metals: Stability leads the list of things to watch for. During storage Copper and its alloys (brasses, bronzes) are known to and handling, fuels may react with their surroundings and cause (catalyze) reactions with all organic materials, with materials in their environment to form undesirable including petroleum fuels, and more so with biodiesel. by-products that can interfere with proper operation. These materials have been used in heating systems for Properly made B100 blend stocks are required to meet decades, and have a good track record. They do not oxidation stability requirements to help minimize this effect. enter into a reaction with the fuel and, therefore, are not Good additive systems for petroleum fuels incorporating consumed (unlike metal exposed to a strong acid) but this stabilizers, dispersants, and metal deactivators catalytic activity can cause the formation of precursors to (FuelArmor™ or similar additive) will help to protect the sludge. -

Energy Facts and Figures

ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT TRANSPORTATION & FUELS UNIVERSITY of WASHINGTON Average vehicle fuel consumption: 24 mpg Non-engine components of vehicle ineciency Primary importance for: 3 CHEM E / ENVIR / M E 341, Autumn 2012 Braking: (1/2)(1 – εb)mv /d Stop-and-go 3 Aerodynamic drag: (1/2)ρcdAfv High speed Rolling resistance: crrmgv Low speed εb = hybrid fraction recovery of braking; m = vehicle mass; v = velocity; d = stopping distance; ρ = density of air; cd = coecient of drag (typ. 0.3); 15 Comm. Fuel cost (Dec. 2012) , higher heating value, Primary Energy Consumption by Source and Sector, 2011 (10 Btu) Resident. A = frontal area; c = coecient of rolling resistance (typ. 0.01) 19% f rr and specic gravity Source Total = 97.3 Sector 22% Average fuel consumption of bus: 3.9 mpg Fuel Unit Cost ($) HHV (Btu) Sp. gr. Percent of Source Percent of Sector Passenger capcities of bus (seated and standing): 120 (60 ft. bus), 60 (40 ft. bus) Crude Oil gal 2.38 138,350 0.88 Transport. Industrial Transport. Average fuel consumption in passenger airplanes: 0.014 gal/psg/nmi Gasoline gal 3.39 124,340 0.74 28% 31% Petroleum 71 93 27.0 Kerosene gal 3.30 135,000 0.80 35.3 23 3 (28%) Relationship of Emissions to Combustion of Oxyhydrocarbon Fuel (CnHmOp) 1 4 Diesel gal 4.03 137,380 0.83 5 (36%) CnHmOp + α(O2 + 3.76 N2) ––> (n - β - γ) CO2 + (m/2)(1 - γ/n) H2O + β CO Heating Oil gal 3.96 139,000 0.92 40 Industrial Consumption by End-Use Sector, 2011 6 41 + γ CH(m/n) + δ O2 + [3.76 - ε/(2x)] N2 + (ε/x) NOx Natural gas MCF 13 1.09 x 10 0.65* Natural Gas 8 20.3 (21%) Coal s. -

Biomass Derivatives Competitive with Heating Oil Costs

Biomass Derivatives Competitive with Heating Oil Costs Transportation fuel Heat or electricity • Data are from literature, except heating oil is adjusted from 2011 winter average • Fuel costs vary widely based on feedstock, location, and technology option • Retail pellet costs are based on current prices in NE (~$243/ton) • Densifying biomass for heating (e.g. pyrolysis oil or pellets) can be a cost- competitive feedstock for residential heating system • These are not “drop-in” fuels for current liquid handling/infrastructure/applications • Logistics and supply chain considerations begin to predominate for residential biothermal 1 Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy eere.energy.gov Biothermal Offers Competitive Economics Particularly in Northeast Bio-oils as a heating oil substitute may present a significant opportunity to solve a relevant problem, save consumers money… particularly in the Northeast Heating Oil Prices and Pyrolysis Oil Price Projections in 2011 40 Heating oil prices are 2011 Biothermal leverages 35 monthly averages per EIA. Pyrolysis oil prices are ongoing work in the OBP 30 bio-oil production and projection. upgrading and other 25 work in thermochemical 20 including: 36.35 •Corrosion/material 15 $/GJ in 2011in $/GJ 25.63 25.75 compatibility 10 20.49 20.73 21.51 •Feedstock logistics and pre-processing 5 •Densification 0 •Fast pyrolysis U.S. New England U.S. New England Raw Pyrolysis Fully Wholesale Wholesale Residential Residential Oils Upgraded Heating Oil Heating Oil Heating Oil Heating Oil Pyrolysis Oils Oil Type and -

Biofuel Requirements in Diesel and Heating

Office of the Chief Economist Office of Energy Policy and New Uses Biofuel in diesel and heating oil Tony Radich Agricultural Economist [email protected] EIA State Heating Oil and Propane Program Workshop Washington, DC July 13, 2016 Office of the Chief Economist Office of Energy Policy and New Uses Agenda •What is distillate fuel and which biofuels are compatible? •Federal, state, and local policies on biofuels in distillate fuel •Economics of biodiesel production, including the effects of biofuels policies OfficeDistillate of the and Chief heating Economist oil overlap but not perfectlyOffice of Energy Policy and New Uses • Distillate fuel consists of No. 2 diesel fuel and No. 2 heating oil – Kerosene (No. 1 fuel oil) is a separate product in EIA data – Blends easily with No. 2 distillate, often used to improve cold flow • “Heating oil” can also refer to grades heavier than No. 2 – No. 6 heating oil is classified as residual fuel by EIA – No. 4 heating oil is a blend of No. 2 and residual fuel • Two trends in heating oil – Reduction in sulfur levels – Addition of biofuels • Diesel and heating oil can contain biodiesel and renewable diesel – Both produced from vegetable oil or animal fat but different production processes – ASTM standards for diesel fuel and heating oil allow 5% biodiesel in fungible products – Blends of up to 20% biodiesel are supported by many engine and burner manufacturers – Renewable diesel can be used in any proportion in diesel or heating oil • Cellulosic diesel and cellulosic heating oil are under development – Both are produced by pyrolysis of wood fiber; more upgrading of pyrolysis oil is required for diesel use OfficeU.S. -

NYC'sgreen Fuel Supplier

NYC’s GREEN Fuel Supplier... January 2010 About Tri-State Biodiesel Founded in 2004 -- funded and developed by environmental advocates and entrepreneurs. Headquartered in New York City with operations throughout New York, and limited operations in New Jersey and Connecticut. NYCs leading biodiesel brand and the first to offer biodiesel fuel to private fleets in the city and oil-to-biodiesel recycling service. About Tri-State Biodiesel TSB is national pioneer in area urban, recycled oils based biodiesel Member of the National Biodiesel Board with large national network of biodiesel production and marketing partners. Management team with over 15 years biodiesel experience that helped to build the biodiesel movement and industry. TSB Services Overview Used cooking oil recycling service Biodiesel fuel and bioheating oil sales Active in biodiesel promotion, education, and outreach legislative support. Tri-State Biodiesel Waste Oil Collection Service Collecting over 1mm gal/ year from 2700 restaurants Employs 26 workers - many from low-income communities Our service saves the city on enforcement and cleanup Convenient for restaurant partners 6 trucks all running on biodiesl fuel Tri-State Biodiesel Fleet Fueling Service Currently fueling over 300 heavy duty fleet trucks in the city Biodiesel fuel provided directly to fleet Biodiesel fuel blended with petroleum diesel either B5 or B20 Fleets include Fresh Direct, Movers Not Shakers, ABC Home & Carpet, and others Some TSB Customers Tri-State Biodiesel Home Bio-heating Oil Service Provides B20 biodiesel/ heating oil blend Can be used in any #2 & 4 heating oil boiler Heating oil consumer is eligible for 20 cent/gallon tax credit Priced at or below petroleum heating oil with credit.