Local Planning in Inner City Residential Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(OHCA) Statistics Manchester, Gorton

Manchester, Gorton - Westminster constituency Local heart and circulatory disease statistics from the British Heart Foundation Health statistics give our staff, volunteers, supporters and healthcare professionals a sense of the scale of the challenges we face as we fight for every heartbeat. The statistics here are based on official surveys and data sources - please see below for references. This is a presentation of key statistics for this area. You can also make any of them into a jpeg by zooming in and using Snipping Tool or Paint. Around Around Around There are around 920 1,300 7,600 2,700 people have been diagnosed people are living with heart people are living with stroke survivors with heart failure by their GP and circulatory diseases coronary heart disease in Manchester Gorton in Manchester Gorton in Manchester Gorton in Manchester Gorton Around Around Around Around 12,000 7,000 1,100 people in Manchester Gorton adults have been 970 people have a faulty gene that have been diagnosed with people have been can cause an inherited high blood pressure diagnosed with diabetes diagnosed with heart-related condition in Manchester Gorton atrial fibrillation in Manchester Gorton in Manchester Gorton Reviewed and updated Jan 2021. Next review due late 2021. Around Other key statistical publications: 25% https://www.bhf.org.uk/statistics of adults 19% in Manchester Gorton of adults smoke How you can help: have obesity in Manchester Gorton https://www.bhf.org.uk/how-you-can-help Contact us for any queries: https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/contact-us -

Official Directory. [Slater's

2110 OFFICIAL DIRECTORY. [SLATER'S COU~CILLORS. WARD. COLLEGIATE CHURCH WARD. Hinchcliffe Thomas Henry. ••.•.••.• St. Luke's Alderman. BinchlifIe lsaac.•.•.•• ,.•.•...•.... St. John's I:John Royle, 36 Dantzio street Bodkin Henry ••••••••••••••••••.• Longsigllt Holden Wllliam.................. .• Hll.rpurhey Councillors. Howarth l}eorge ••••.•••••.•••...• N ew Cr(J~s !John Richard Smith, 27 ~hfield road, Urmston Howell Hiram .J:;;dward •••••..•.•.. ClteethRJn "Ernest Darker, 26 SW!ln street Hoyle Thomas ••.••..•...•..••.•.• St. Michael's tJohn J,owry, Whol8l;ale Fish market, HiJi(h street JackJlon William Turnt>r...... •••. .• Harpurhey CRUMPSALL WARD. J ennison Angelo. ••• .. ••••••.•••.•.• Longsight Alderm.an. JohDBon James ••••••• '...... .•••.• St. Luke's J ohnston J a.me8.. .• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• .• Blackley and Moston IIEdward Holt, Derby Brewery, Cheetham J Olles John ••••••.••••••.••••••• I• Longsight Councillors. Jone8 John T •.•.. "' .....••.•..•.• New Cross tHarold Wood, The Wichnors, t3ingleton road, KerBal Kay William •....... _........... .• St. Georgc's -Frederick Todd, Waterloo st. Lower Crumpsall Kemp Jamea Miles Platting tFrederick John Robertshaw, Ivy House, Kea.rsley rd. Ol"llmpaall Kendall John James................ Oheetham DIDSBURY WARD. Lane-Scott William Fitzmaurtce.... Rusholrne Langley J ames Birchby •• ..•..••• •• St. Clement's AlcUrman. LecomtJer William Godfrey ••••••.• Medlock Street 11 WaIter Edward Harwood, 78 CrOSl! street Litton John George •• •••• .• •. •• .• •• St. Ann's Oouncillorl. Lofts John Albert................. -

Whalley Range and Around Key

Edition Winter 2013/14 Winter Edition 2 nd Things about Historical facts, trivia and other things of interest Alexandra Park Manley Hall Primitive Methodist College The blitz 1 9 Wealthy textile merchant 12 Renamed Hartley Victoria College after its 16 The bombs started dropping on The beginning: Designed Samuel Mendel built a 50 benefactor Sir William P Hartley, was opened in Manchester during Christmas 1940 with by Alexander Hennell and the Range room mansion in the 1879 to train men to be religious ministers. homes in the Manley Park area taking opened in 1870, the fully + MORE + | CLUBS SPORTS | PARKS | SCHOOLS | HISTORY | LISTINGS | TRIVIA 1860s, with extensive Now known as Hartley Hall, it is an several direct hits. Terraced houses in public park (named after gardens running beyond independent school. Cromwell Avenue were destroyed and are Princess Alexandra) was an Bury Avenue and as far as noticeable by the different architecture. During oasis away from the smog PC Nicholas Cock, a murder Clarendon Road (pictured air raids people would make their way to a of the city and “served to 13 In the 1870s a policeman was fatally wounded left). Mendel’s business shelter, one of which was (and still is!) 2.5m deter the working men whilst investigating a disturbance at a house collapsed when the Suez under Manley Park and held up to 500 people. of Manchester from the near to what was once the Seymour Hotel. The Origins: Whalley Range was one of Manchester’s, and in fact Canal opened and he was The entrance was at the corner of York Avenue alehouses on their day off”. -

Buses Serving North Manchester General Hospital

Buses serving North Manchester General Hospital 52 Salford Shopping City, Broughton, Cheetham Hill, NMGH, Harpurhey, Moston, Newton Heath, Failsworth Tesco Bus Stops Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester A,C, Pendleton Higher Broughton Cheetham Hill NMG Moston Newton Heath Brookdale Failsworth D,E,F Salford Shopping City McDonalds Crescent Road Hospital Ben Brierley Dean Lane Park Tesco Store 27 16 7 12 21 26 32 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 53 Cheetham Hill, NMGH, Harpurhey, Miles Platting, SportCity, Gorton, Belle Vue, Longsight, Rusholme, Central Manchester Bus Stops Hospitals, Hulme, Old Trafford A,C, Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester D,E,F Cheetham Hill NMG Harpurhey Sport Gorton Belle Rusholme University Old Trafford Salford Crescent Road Hospital Rochdale Rd City Vue of Manchester Trafford Bar Shopping City 7 7 16 31 35 50 58 68 80 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 88=> Circulars, Manchester City Centre, Monsall, Moston, White Moss, Blackley, NMGH, Cheetham Hill, Manchester City Centre 89<= Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester (Evenings, Sundays and Bank Holidays—JPT) Use these buses and change at Crumpsall Metrolink Station or Cheetham Hill, Cheetham Hill Rd (Bus 135) for Bury. Bus Stops Manchester Central Moston White Blackley Bank Crumpsall NMG Cheetham Manchester -

MANCHESTER, St Augustine [Formerly Granby Row, Later York

MM MAGHULL, St George; Archdiocese of Liverpool C 1887-1941 M 1880-1941 Copy reg Microfilm MF 9/126 MANCHESTER, All Saints see St Augustine MANCHESTER, St Augustine [formerly Granby Row, later York Street, now Grosvenor Square, All Saints]; Diocese of Salford C 1820-1826, 1856-1879 M 1837-1922 Orig reg RCMA 1889-1920 C 1820-1826, 1856-1900 M 1837-1900 Copy reg Microfilm MF 9/248-251 C 1870-1900 Copy reg Microfilm MF 1/203 C 1838-1900 Copy Microfilm MF 9/251 index C 1947-1962 M 1947-1954, 1961-1962 Reg rets RCSF 2 MANCHESTER, St Casimir (Oldham Road) see MANCHESTER, Collyhurst MANCHESTER, St Joseph (Goulden Street); Diocese of Salford [closed] C 1852-1903 M 1856-1904 Orig reg RCMJ C 1852-1903 M 1856-1904 Copy reg Microfilm MF 9/253-254 C 1873-1887 M 1885-1904 Copy reg Microfilm MF 1/243 C 1856-1903 Copy Microfilm MF 9/254 index For references in bold e.g. RCLN, please consult catalogues for individual register details and the full reference. For records in the Searchroom held on microfiche, microfilm or in printed or CRS format, please help yourself or consult a member of the Searchroom Team. 1 MM MANCHESTER, St Mary (Mulberry Street) [The Hidden Gem]; Diocese of Salford C 1794-1932 M 1837-1965 Orig reg RCMM C 1794-1922 M 1831-1903 B 1816-1825,1832-1837 Copy reg Microfilm MF 9/21-25 C 1947-1962 M 1947-1954, 1961-1962 Reg rets RCSF 2 C 1794-1819 B 1816-1825 Copy reg Microfilm DDX 241/24 C 1820-1831 Transcript CD Behind “Issue desk” in Searchroom C 1870-1941 M 1871-1941 Copy reg Microfilm MF 1/240-241 C 1850-1949 M 1837-1938 Copy Microfilm MF 9/25 index C 1870-1941 Index Microfilm MF 1/241 MANCHESTER, Livesey Street, see MANCHESTER, Collyhurst MANCHESTER, Ancoats, St Alban; Diocese of Salford [closed] C 1863-1960 M 1865-1959 D 1948-1960 Orig reg RCMN C 1863-1960 M 1865-1959 D 1948-1960 Copy reg MF 9/218-219 C 1947-1953, 1955-1960 M 1947-1954 Reg rets RCSF 2 C 1870-1941 M 1865-1941 Copy reg Microfilm MF 1/228-229 For references in bold e.g. -

The Fallowfield Loop Is Thought to Be the Longest Urban Cycle Way in Britain

THE MANCHESTER CYCLEWAY / FALLOWFIELD LOOP USEFUL WEBSITES At almost eight miles long, the Fallowfield Loop is thought to be the longest urban cycle way in Britain. It connects the districts of Friends of the Fallowfield Loop: Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Fallowfield, Levenshulme, Gorton and Fairfield www.cycle-routes.org/fallowfieldloopline/ via an off-road cycle path, which both pedestrians and horse riders can also share. It also creates a linear park and wildlife corridor, CTC: The UK’s national cyclists’ organisation: www.ctc.org.uk linking parks and other open spaces. Previously a railway line, the route forms part of Routes 6 and 60 of the National Cycle Network GMCC: The Greater Manchester Cycle Campaign: developed, built and maintained by Sustrans. www.gmcc.org.uk Sustrans is the UK’s leading sustainable transport charity, working Sustrans: A charity that works on practical projects to encourage on practical projects so people choose to travel in ways that benefit people to walk, cycle and use public transport: their health and the environment. The charity is behind many www.sustrans.org.uk groundbreaking projects including the National Cycle Network, over 12,000 thousand miles of traffic-free, quiet lanes and on-road CycleGM: The official cycling website of the 10 Authorities of walking and cycling routes around the UK. Greater Manchester: www.cyclegm.org The Fallowfield Loop The Friends of the Fallowfield Loop website offers a wealth of information about the history of the Loop, arranged cycles, events, Greater Manchester Road Safety: www.gmroadsafety.co.uk and activities going on in and around the area. -

My Wild City Charlestown by Wilder Place to Be

WILDLI YOUR FE A R CITY, YOUR G RDEN, YOU MyWildCity www.lancswt.org.uk Cover Image by Tom Marshall. HOW LINKING UP OUR GARDENS 49% CAN MAKE of Manchester’s land cover is made up of dlife within green and blue & wil their A CHANGE… ople garde (water) spaces ting pe ns mywildReconnec City We want to help make Green space on Higher Blackley Manchester a greener, your doorstep My Wild City Charlestown by wilder place to be. is a new campaign run Living in an industrial city Crumpsall The Wildlife Trust for The My Wild City scheme is a can sometimes make you Moston Harpurhey Lancashire, Manchester and national initiative from The Wildlife feel as if you are somehow Trusts, which is already running very North Merseyside, that aims Cheetham disconnected from nature. Miles Platting & to reconnect people with their successfully in several cities including Newton Heath Bristol, Cardiff, London and Leeds. However, research we helped to gardens and the wildlife living Ancoats & Clayton within them. We want to add Manchester conduct in 2016-18 led by Manchester Metropolitan University called CITY to the list of Wild Cities, CENTRE Bradford To do this we must link ‘My Back Yard’, found that 49% up our green spaces but we need your help. of Manchester’s land cover Hulme Ardwick Gorton North and gardens to save is made up of green and blue local wildlife. (water) spaces. Rusholme Longsight Whalley Moss Gorton South Collectively, gardens make up Range Side Fallowfield 20% of this green space across Levenshulme Old Manchester – so the power is in Chorlton Moat Chorlton Withington all of our hands to get stuck in Park and make a difference. -

Manchester Migration a Profile of Manchester’S Migration Patterns

Manchester Migration A Profile of Manchester’s migration patterns Elisa Bullen Public Intelligence Performance and Intelligence Chief Executive’s Department Date: March 2015 Version 2015/v1.3 www.manchester.gov.uk Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................3 Manchester’s Migration History ..................................................................................................................... 3 International migration trends ................................................................................................................ 3 Internal migration trends ........................................................................................................................4 Household movement ...................................................................................................................................5 Households moving within a ward ......................................................................................................... 8 Households moving from one Manchester ward to another ................................................................... 9 Long-term International Migration ............................................................................................................... 11 Wards popular with recent movers from abroad .................................................................................. 13 Country of birth ................................................................................................................................... -

School Bus Services in Manchester

Effective 1 September 2020 Burnage Academy for Boys 0900 – 1515 The following bus services run close by - details can be found at www.tfgm.com: Stagecoach service 25 – Stockport, Heaton Norris, Heaton Moor, Chorlton, Stretford, Lostock, Davyhulme Stagecoach service 50 – East Didsbury, Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester, Pendleton, Salford Quays Stagecoach service 171 – Newton Heath, Clayton, Openshaw, Gorton, Ryder Brow, Levenshulme, East Didsbury, Didsbury Stagecoach service 172 – Newton Heath, Clayton, Openshaw, Gorton, Ryder Brow, Levenshulme, West Didsbury Stagecoach service 197 – Stockport, Heaton Moor, Levenshulme, Longsight, Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester Additionally specific schoolday only services also serve the school as follows: Stagecoach Service 748 – Gorton, Ryder Brow, Levenshulme Stagecoach Service 749 – Whalley Range, Moss Side, Longsight, Levenshulme Stagecoach Service 751 (PM Only) – Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester Stagecoach Service 797 (PM Only) – Levenshulme, Longsight, Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester Gorton / Ryder Brow / Levenshulme Service 748 TfGM Contract: 0443 TfGM Contract: 5089 Minimum Capacity: 90 Minimum Capacity: 52 Operator Code: STG Operator Code: BEV Gorton, Tesco 0820 Burnage Academy 1545 Ryder Brow, Station 0824 Levenshulme, Station 1552 Mount Road/Matthews Lane 0828 Mount Road/Matthews Lane 1558 Levenshulme, Station 0835 Ryder Brow, Station 1601 Burnage Academy 0845 Gorton, Tesco 1609 Service 748 route: From Gorton, Tesco via Garratt Way, Whitwell Way, Knutsford Road, Brookhurst Road, Levenshulme -

The Heart of Whalley Range

April/May issue 2017 https://www.facebook.com/CelebrateFestivalWhalleyRange/ The Heart of Whalley Range The countdown to the 20th Celebrate Festival is well under way, and it's looking like it could be the best yet. The theme this year is "Love Whalley Range", so we're celebrating what's great about where Congratulations to Chris Ricard from Whalley Range we live. Local performers on the main stage include Community Forum for winning the 2017 favourites Boz Hayward and the Chorlton Rock Out Our Manchester Women Intergenerational Award. School, who will be joined by Celebrate newcomers Also to Finalist Justin Garner from the Whiz Project for his Rangeela and Vieka Plays, whilst the acoustic area stunning Outdoor Photographer of the Year entry! will host solo artists and interactive workshops. Did you know that Whalley Range is home to TWO circuses? And this year they are both joining us to provide free workshops for all ages - Higher State Aerial Entertainment return with their popular aerial hoop lessons, whilst Travelling Light Circus will teach you how to spin poi and hula hoop. There's lots more workshops inside the makers tent too, and if you've got little ones you'll be excited to know that the bouncy castle will be FREE between midday and 1pm. The Age-friendly and Health & Wellbeing marquee will feature intergenerational activities, local information and health advice too: there's something for people of all ages at Celebrate! Volunteers are welcome: contact us on 881 3744 or by email: [email protected] See you there! We are pleased to say that the Whiz youth centre is now a credited Duke of Edinburgh’s Award provider. -

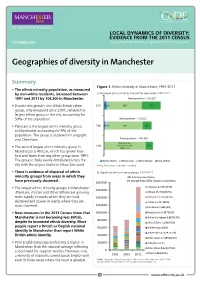

Geographies of Diversity in Manchester

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Manchester Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Manchester, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased between a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 1991 and 2011 by 104,300 in Manchester. Total population – 503,127 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 5% 2% 59% 33% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city, accounting for 59% of the population. Total population – 422,922 • Pakistani is the largest ethnic minority group 2001 2% 4% 74% 19% in Manchester accounting for 9% of the population. The group is clustered in Longsight and Cheetham. Total population – 432,685 85% (includes 1991 White Other and 15% • The second largest ethnic minority group in White Irish Manchester is African, which has grown four- fold and faster than any other group since 1991. The group is fairly evenly distributed across the White Other White Irish White British Non-White city with the largest cluster in Moss Side ward. Notes: Figures may not add due to rounding. • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 minority groups from areas in which they 2011 Census estimates (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. 180,000 • The largest ethnic minority groups in Manchester Pakistani 42,904 (73%) 160,000 (Pakistani, African and Other White) are growing African 25,718 (254%) more rapidly in wards where they are least 140,000 Chinese 13,539 (142%) clustered and slower in wards where they are Indian 11,417 (80%) 120,000 most clustered. -

Healthy Me Healthy Communities Services for Central

0 G A T A N O C COMPILED BY R O G AT N S I MANCHESTER S T BESWICK 5 3 6 A63 MILES 5 ASHTON OLD R A PLATTING OAD Old Abbey Taphouse COMMUNITY GROCER* Hulme Community Hub offering hot meals A57(M) WEST Anson Cabin Project and Anson & necessity deliveries, newsletter, radio GORTON A Ardwick 50 COMMUNITY Childrens ARDWICK Community House (also hosts HMHC Grab & Go) Hulme 6 GORTON GROCER* station & live streaming, befriending service. 7 C Centre H Abbey Hey Lane i COVERDALE h g Park Zion Community h & NEWBANK Providing support and activities for children, o e r A G Resource Centre C COMMUNITY orto r n Contact: Rachele 07905271883 Martenscroft a La l Childrens m 3 GROCER* ne to O b young people and adults of all ages. Centre r 4 Z Arts i d x or Craig 07835166295 n g e fo Road S t r Ardwick Contact: 0161 248 569 or Trinity Sports d Sports Hall [email protected] L Leisure A 4 l o HULME P R A 57A57 y e d Aquarius n o HY [email protected] 6 HULME c S H Centre r a t Moss Side o DY COMMUNITY r d Gorton South Gorton ED e f Leisure Centre 3 t BELLE E Guildhall Close, Manchester Science Park e Active RD GROCER* Childrens Sacred Heart www.ansoncabin.co.uk t R W Lifestyles OA N Centre Childrens a y o Centre Centre Y r t Kath Locke VUE h 1 M15 6SY Centre A Meldon Road, Manchester M13 0TT oss L M a n e Ea A s M t W Whitworth o N u MOSS n K Park t S Gorton Day Centre R R o Moss L ane East O Pakistani a Levenshulme Inspire d SIDE Rusholme Community A N Childrens Moss Side Age UK Centre Food parcels, shopping and prescription P Centre Powerhouse U R Meal deliveries, wellbeing support and p O p LONGSIGHT S e deliveries, and wellbeing support.