Math, Music and Identity CD #1: Symmetry in Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barber Piano Sonata in E-Flat Minor, Opus 26

Barber Piano Sonata In E-flat Minor, Opus 26 Comparative Survey: 29 performances evaluated, September 2014 Samuel Barber (1910 - 1981) is most famous for his Adagio for Strings which achieved iconic status when it was played at F.D.R’s funeral procession and at subsequent solemn occasions of state. But he also wrote many wonderful songs, a symphony, a dramatic Sonata for Cello and Piano, and much more. He also contributed one of the most important 20th Century works written for the piano: The Piano Sonata, Op. 26. Written between 1947 and 1949, Barber’s Sonata vies, in terms of popularity, with Copland’s Piano Variations as one of the most frequently programmed and recorded works by an American composer. Despite snide remarks from Barber’s terminally insular academic contemporaries, the Sonata has been well received by audiences ever since its first flamboyant premier by Vladimir Horowitz. Barber’s unique brand of mid-20th Century post-romantic modernism is in full creative flower here with four well-contrasted movements that offer a full range of textures and techniques. Each of the strongly characterized movements offers a corresponding range of moods from jagged defiance, wistful nostalgia and dark despondency, to self-generating optimism, all of which is generously wrapped with Barber’s own soaring lyricism. The first movement, Allegro energico, is tough and angular, the most ‘modern’ of the movements in terms of aggressive dissonance. Yet it is not unremittingly pugilistic, for Barber provides the listener with alternating sections of dreamy introspection and moments of expansive optimism. The opening theme is stern and severe with jagged and dotted rhythms that give a sense of propelling physicality of gesture and a mood of angry defiance. -

The Critical Reception of Beethoven's Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op

The Critical Reception of Beethoven’s Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op. 124 Translated and edited by Robin Wallace © 2020 by Robin Wallace All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-7348948-4-4 Center for Beethoven Research Boston University Contents Foreword 6 Op. 123. Missa Solemnis in D Major 123.1 I. P. S. 8 “Various.” Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 1 (21 January 1824): 34. 123.2 Friedrich August Kanne. 9 “Beethoven’s Most Recent Compositions.” Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung mit besonderer Rücksicht auf den österreichischen Kaiserstaat 8 (12 May 1824): 120. 123.3 *—*. 11 “Musical Performance.” Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode 9 (15 May 1824): 506–7. 123.4 Ignaz Xaver Seyfried. 14 “State of Music and Musical Life in Vienna.” Caecilia 1 (June 1824): 200. 123.5 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of May.” 15 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 26 (1 July 1824): col. 437–42. 3 contents 123.6 “Glances at the Most Recent Appearances in Musical Literature.” 19 Caecilia 1 (October 1824): 372. 123.7 Gottfried Weber. 20 “Invitation to Subscribe.” Caecilia 2 (Intelligence Report no. 7) (April 1825): 43. 123.8 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of March.” 22 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 29 (25 April 1827): col. 284. 123.9 “ .” 23 Allgemeiner musikalischer Anzeiger 1 (May 1827): 372–74. 123.10 “Various. The Eleventh Lower Rhine Music Festival at Elberfeld.” 25 Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 156 (7 June 1827). 123.11 Rheinischer Merkur no. 46 27 (9 June 1827). 123.12 Georg Christian Grossheim and Joseph Fröhlich. 28 “Two Reviews.” Caecilia 9 (1828): 22–45. -

Beethoven (1819-1823) (1770-1827)

Friday, May 10, 2019, at 8:00 PM Saturday, May 11, 2019, at 3:00 PM MISSA SOLEMNIS IN D, OP. 123 Ludwig van Beethoven (1819-1823) (1770-1827) Tami Petty, soprano Helen KarLoski, mezzo-soprano Dann CoakwelL, tenor Joseph Beutel, bass-baritone Kyrie GLoria Credo Sanctus and Benedictus* Agnus Dei * Jorge ÀviLa, violin solo Approximately 80 minutes, performed without intermission. PROGRAM NOTES The biographer Maynard SoLomon him to conceptuaLize the Missa as a work described the Life of Ludwig van of greater permanence and universaLity, a Beethoven (1770-1827) as “a series of keystone of his own musicaL and creative events unique in the history of personaL Legacy. mankind.” Foremost among these creative events is the Missa Solemnis The Kyrie and GLoria settings were (Op. 123), a work so intense, heartfeLt and largely complete by March of 1820, with originaL that it nearly defies the Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus and categorization. Agnus Dei foLLowing in Late 1820 and 1821. Beethoven continued to poLish the work Beethoven began the Missa in 1819 in through 1823, in the meantime response to a commission from embarking on a convoLuted campaign to Archduke RudoLf of Austria, youngest pubLish the work through a number of son of the Hapsburg emperor and a pupiL competing European houses. (At one and patron of the composer. The young point, he represented the existence of no aristocrat desired a new Mass setting for less than three Masses to various his enthronement as Archbishop of pubLishers when aLL were one and the Olmütz (modern day Olomouc, in the same.) A torrent of masterworks joined Czech RepubLic), scheduLed for Late the the Missa during this finaL decade of following year. -

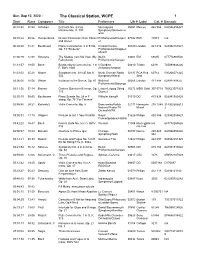

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Sep 13, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 07:52 Schubert Entr'acte No. 3 from Minneapolis 05051 Mercury 462 954 028946295427 Rosamunde, D. 797 Symphony/Skrowacze wski 00:10:2208:46 Humperdinck Dream Pantomime from Hansel Philharmonia/Klemper 07382 EMI 13073 n/a and Gretel er 00:20:0838:41 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Curzon/Vienna 04349 London 421 616 028942161627 Op. 73 "Emperor" Philharmonic/Knappert sbusch 01:00:19 12:38 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My Berlin 03600 EMI 69005 077776900520 Fatherland) Philharmonic/Karajan 01:13:5718:05 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in Il Giardino 04810 Teldec 6019 745099844226 F, BWV 1046 Armonico/Antonini 01:33:02 25:28 Mozart Symphony No. 39 in E flat, K. North German Radio 02135 RCA Red 60714 090266071425 543 Symphony/Wand Seal 02:00:0010:56 Weber Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65 National 00266 London 411 898 02894189820 Philharmonic/Bonynge 02:11:56 37:14 Brahms Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. Leister/Leipzig String 10273 MDG Gold 307 0719 760623071923 115 Quartet 02:50:1008:00 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 24 in F Wilhelm Kempff 01310 DG 415 834 028941583420 sharp, Op. 78 "For Therese" 02:59:40 29:21 Karlowicz Violin Concerto, Op. 8 Danczowka/Polish 02170 Harmonia 278 1088 314902505612 National Radio-TV Mundi 2 Orchestra/Wit 03:30:0111:19 Wagner Prelude to Act 1 from Parsifal Royal 01626 Philips 420 886 028942088627 Concertgebouw/Haitink 03:42:2016:47 Bach French Suite No. -

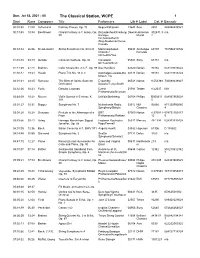

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Jul 18, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 11:00 Schumann Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 Segev/Pohjonen 13643 Avie 2389 822252238921 00:13:4518:34 Beethoven Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. Bezuidenhout/Freiburg DownloadHarmonia 902431.3 n/a 80 Baroque Mundi 2 Orchestra/Zurich Zing-Akademie/Heras- Casado 00:33:34 26:06 Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 08 in D Metamorphosen 05480 Archetype 60107 701556010726 Chamber Records Orchestra/Yoo 01:01:1009:19 Dvorak Carnival Overture, Op. 92 Cleveland 05021 Sony 63151 n/a Orchestra/Szell 01:11:2927:48 Brahms Cello Sonata No. 2 in F, Op. 99 Diaz/Sanders 02520 Dorian 90165 053479016522 01:40:47 19:24 Haydn Piano Trio No. 43 in C Kalichstein-Laredo-Ro 02473 Dorian 90164 053479016423 binson Trio 02:01:4129:45 Rameau The Birth of Osiris (Suite for Ensemble 06541 Naxos 8.553388 730099438827 Orchestra) Savaria/Terey-Smith 02:32:26 10:43 Fucik Danube Legends Czech 01781 Teldec 8.42337 N/A Philharmonic/Neuman 02:44:0915:48 Mozart Violin Sonata in E minor, K. Uchida/Steinberg 04768 Philips B000411 028947565628 304 5 03:01:27 35:31 Dopper Symphony No. 7 Netherlands Radio 03512 NM 92060 871330992060 Symphony/Bakels Classics 4 03:38:2810:28 Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a BRT 07909 Naxos 8.570011- 074731300117 Faun Philharmonic/Rahbari 12 0 03:49:56 09:43 Grieg Homage March from Sigurd Eastman Rochester 05011 Mercury 434 394 028943439428 Jorsalfar, Op. 56 Pops/Fennell 04:01:0912:36 Bach Italian Concerto in F, BWV 971 Angela Hewitt 03592 Hyperion 67306 D 138602 04:14:4530:55 Diamond Symphony No. -

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra War and Peace

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra War and Peace Jane Glover, Music Director Jane Glover, conductor William Jon Gray, chorus director Soprano Violin 1 Flute Laura Amend Robert Waters, Mary Stolper Sunday, May 17, 2015, 7:30 PM Alyssa Bennett concertmaster Pick-Staiger Concert Hall, Evanston Bethany Clearfield Kevin Case Oboe Sarah Gartshore* Teresa Fream Robert Morgan, principal Monday, May 18, 2015, 7:30 PM Katelyn Lee Kathleen Brauer Peggy Michel Harris Theater, Chicago (Millennium Park) Hannah Dixon Michael Shelton McConnell Ann Palen Clarinet Sarah Gartshore, soprano Susan Nelson Steve Cohen, principal Kathryn Leemhuis, mezzo-soprano Anne Slovin Violin 2 Daniel Won Ryan Belongie, countertenor Alison Wahl Sharon Polifrone, Zach Finkelstein, tenor Emily Yiannias principal Bassoon Roderick Williams, baritone Fox Fehling William Buchman, Alto Ronald Satkiewicz principal Te Deum for the Victory of Dettingen, HWV 283 George Frideric Handel Ryan Belongie* Rika Seko Lewis Kirk (1685–1759) Julie DeBoer Paul Vanderwerf 1. Chorus: We praise Thee, o God Julia Elise Hardin Horn 2. Soli (alto, tenor) and Chorus: All the earth doth worship Thee Amanda Koopman Viola Jon Boen, principal 3. Chorus: To Thee all angels cry aloud Kathryn Leemhuis* Elizabeth Hagen, Neil Kimel 4. Chorus: To Thee Cherubim and Seraphim Maggie Mascal principal 5. Chorus: The glorious company of the apostles Emily Price Terri Van Valkinburgh Trumpet 6. Aria (baritone) and Chorus: Thou art the King of Glory Claudia Lasareff-Mironoff Barbara Butler, 7. Aria (baritone): When Thou tookest upon Thee Tenor Benton Wedge co-principal 8. Chorus: When Thou hadst overcome Madison Bolt Charles Geyer, 9. Trio (alto, tenor, baritone): Thou sittest at the right hand of God Zach Finkelstein* Cello co-principal 10. -

Defining Musical Americanism: a Reductive Style Study of the Piano Sonatas of Samuel Barber, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, and Charles Ives

Defining Musical Americanism: A Reductive Style Study of the Piano Sonatas of Samuel Barber, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, and Charles Ives A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Brendan Jacklin BM, Brandon University, 2011 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2013 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD Abstract This document includes a reductive style study of four American piano sonatas premiered between 1939 and 1949: Piano Sonata No. 2 “Concord” by Charles Ives, Piano Sonata by Aaron Copland, Piano Sonata by Elliott Carter, and Piano Sonata, Op. 26 by Samuel Barber. Each of these sonatas represents a different musical style and synthesizes traditional compositional techniques with native elements. A reductive analysis ascertains those musical features with identifiable European origins, such as sonata-allegro principle and fugue, and in doing so will reveal which musical features and influences contribute to make each sonata stylistically American. While such American style elements, such as jazz-inspired rhythms and harmonies, are not unique to the works of American composers, I demonstrate how the combination of these elements, along with the extent each composer’s aesthetic intent in creating an American work, contributed to the creation of an American piano style. i Copyright © 2017 by Brendan Jacklin. All rights reserved. ii Acknowledgments I would first like to offer my wholehearted thanks to my advisor, Dr. bruce mcclung, whose keen suggestions and criticisms have been essential at every stage of this document. -

SAMUEL BARBER Evening During Term in the College Chapel and Presents an Annual Concert Series

559053bk Barber 15/6/06 9:51 pm Page 5 Choir of Ormond College, University of Melbourne Deborah Kayser Deborah Kayser performs in areas as diverse as ancient Byzantine chant, French and German Baroque song and In June and July of 2005 the Choir of Ormond College gave its eleventh international concert tour, visiting classical contemporary music, both scored and improvised. Her work has led her to tour regularly both within AMERICAN CLASSICS Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Poland and Italy. Other tours have included New Zealand, Singapore, Japan, Australia, and internationally to Europe and Asia. She has recorded, as soloist, on numerous CDs, and her work is Holland, England, Scotland, Switzerland and Belgium. These tours have received outspoken praise from the public frequently broadcast on ABC FM. As a member of Jouissance, and the contemporary music ensembles Elision and and critics alike. The choir was formed by its Director; Douglas Lawrence, Master of the Chapel Music, in 1982. Libra, she has performed radical interpretations of Byzantine and Medieval chant, and given premières of works There are 24 Choral Scholars: ten sopranos, four altos, four tenors, and six basses. The choir sings each Sunday written specifically for her voice by local and overseas composers. Her performance highlights include works by SAMUEL BARBER evening during term in the College chapel and presents an annual concert series. Each year a number of outside composers Liza Lim, Richard Barrett and Chris Dench, her collaboration with bassist Nick Tsiavos, and oratorio and engagements are undertaken. These have included concerts for the Australian Broadcasting Commission, Musica choral works with Douglas Lawrence. -

Graduate-Dissertations-21

Ph.D. Dissertations in Musicology University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Music 1939 – 2021 Table of Contents Dissertations before 1950 1939 1949 Dissertations from 1950 - 1959 1950 1952 1953 1955 1956 1958 1959 Dissertations from 1960 - 1969 1960 1961 1962 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 Dissertations from 1970 - 1979 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 Dissertations from 1980 - 1989 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 Dissertations from 1990 - 1999 1990 1991 1992 1994 1995 1996 1998 1999 Dissertations from 2000 - 2009 2000 2001 2002 2003 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Dissertations since 2010 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2018 2019 Dissertations since 2020 2020 2021 1939 Peter Sijer Hansen The Life and Works of Dominico Phinot (ca. 1510-ca. 1555) (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1949 Willis Cowan Gates The Literature for Unaccompanied Solo Violin (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Gwynn Spencer McPeek The Windsor Manuscript, British Museum, Egerton 3307 (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Wilton Elman Mason The Lute Music of Sylvius Leopold Weiss (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1950 Delbert Meacham Beswick The Problem of Tonality in Seventeenth-Century Music (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1952 Allen McCain Garrett The Works of William Billings (under the direction of Glen Haydon) Herbert Stanton Livingston The Italian Overture from A. Scarlatti to Mozart (under the direction of Glen Haydon) 1953 Almonte Charles Howell, Jr. The French Organ Mass in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (under the direction of Jan Philip Schinhan) 1955 George E. -

The Increasing Expressivities in Slow Movements of Beethoven's Piano

The Increasing Expressivities in Slow Movements of Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: Op. 2 No. 2, Op. 13, Op. 53, Op. 57, Op. 101 and Op. 110 Li-Cheng Hung A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Robin McCabe, Chair Craig Sheppard Carole Terry Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2019 Li-Cheng Hung University of Washington Abstract The Increasing Expressivities in Slow Movements of Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: Op. 2 No. 2, Op. 13, Op. 53, Op. 57, Op. 101 and Op. 110 Li-Cheng Hung Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Robin McCabe School of Music Ludwig van Beethoven’s influential status is not only seen in the keyboard literature but also in the entire music world. The thirty-two piano sonatas are especially representative of his unique and creative compositional style. Instead of analyzing the structure and the format of each piece, this thesis aims to show the evolution of the increasing expressivity of Beethoven’s music vocabulary in the selected slow movements, including character markings, the arrangements of movements, and the characters of each piece. It will focus mainly on these selected slow movements and relate this evolution to changes in his life to provide an insight into Beethoven himself. The six selected slow movements, Op. 2 No. 2, Op.13 Pathétique, Op. 53 Waldstein, Op. 57 Appassionata, Op. 101 and Op. 110 display Beethoven’s compositional style, ranging from the early period, middle period and late period. -

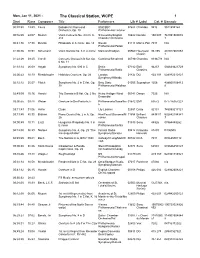

Mon, Jan 11, 2021 - the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Mon, Jan 11, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 13:59 Fauré Ballade for Piano and Stott/BBC 07688 Chandos 9416 9511594162 Orchestra, Op. 19 Philharmonic/Tortelier 00:16:2924:07 Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, K. Sitkovetsky/English 10822 Novalis 150 007 761991500072 218 Chamber Orchestra 7 00:41:36 17:30 Dvorak Rhapsody in A minor, Op. 14 Slovak 01118 Marco Polo 7013 N/A Philharmonic/Pešek 01:00:3620:53 Schumann Violin Sonata No. 3 in A minor Malikian/Kradjian 05560 Haenssler 98.355 401027601053 Classic 1 01:22:29 09:45 Corelli Concerto Grosso in B flat, Op. Cantilena/Shepherd 00794C Chandos 8336/7/8 N/A 6 No. 11 01:33:1426:09 Haydn Symphony No. 090 in C Berlin 07182 EMI 94237 094639423729 Philharmonic/Rattle Classics 02:00:53 10:19 Mendelssohn Hebrides Overture, Op. 26 London 01435 DG 423 104 028942310421 Symphony/Abbado 02:12:1235:57 Fibich Symphony No. 2 in E flat, Op. Brno State 01355 Supraphon 1256 498800106413 38 Philharmonic/Waldhan 8 s 02:49:0910:16 Handel Trio Sonata in B flat, Op. 2 No. Heinz Holliger Wind 00341 Denon 7026 N/A 3 Ensemble 03:00:5509:48 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Philharmonia/Sawallisc 01642 EMI 69572 077776957227 h 03:11:4301:06 Heller Etude Lily Laskine 02591 Erato 92131 745099213121 03:13:49 45:30 Brahms Piano Quartet No. 2 in A, Op. Han/Faust/Giuranna/M 11858 Brilliant 94381/1 502842194381 26 eunier Classics 7 04:00:4910:11 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. -

Sacred Music

SACRED MUSIC MEMORIAL CHAPEL – NOV 9TH - 7:30 PM CHAPEL SINGERS - UNIVERSITY CHOIR - BEL CANTO NOVEMBER 9TH, 2018 - 8PM MEMORIAL CHAPEL Sainte-Chapelle Eric Whitacre (b. 1970) An innocent girl Entered the chaepl: And the angels in the glass Softly sang, “Hosanna in the highest!” CHORAL CONCERT Friday, November 9, 2018 - 8 p.m. The innocent girl MEMORIAL CHAPEL Whispered, “Holy! Holy! Holy!” Chapel Singers Dr. Nicholle Andrews, director Light filled the chamber, Many-coloured light; Saul Egil Hovland (1924-2013) She heard her voice Dr. Hyunju Hwang, organ Echo, Marco Schindelmann, narrator Narrator: “Holy! Holy! Holy!” And on that day a great persecution arose against the church is Jerusalem: and they were all scattered throughout the region of Judea and Softly the angels sang, Samaria, except the apostles, Devout men buried Stephen and made great lamentations over him. “Lord God of Hosts, Heaven and earth are full But Saul laid waste the church, and entering house after house, he Of your glory! dragged off men and women and committed them to prison. Now those Hosannah in the highest! who were scattered went about preaching the word. Unclean spirits came Hosannah in the highest!” out of many who were possessed, crying with a loud voice; and many who were paralyzed, or lame were healed. Her voice becomes light, And the light sings, Choir: Saul still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord. Holy! Holy! Holy!” Narrator & Choir: The light sings soft, He went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues at Damascus.