2014 Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMR 11655 Hot Jive

Hot Jive Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Günter Noris EMR 11655 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd rd 4 2 Flute 1 3 Trombone + th 1 Oboe (optional) 1 4 Trombone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 E Bass st 5 1 B Clarinet 2 B Bass 4 2nd B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 3rd B Clarinet 2 Piano / Keyboard / Guitar (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 String Bass / Bass Guitar (optional) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 1 Congas 2 1st E Alto Saxophone 1 Drums nd 1 2 E Alto Saxophone st 2 1 B Tenor Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts nd 1 2 B Tenor Saxophone st 1 1 B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) nd 1 2 B Trombone nd 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 2 2 Flugelhorn rd rd st 1 3 B Trombone 2 3 Flugelhorn 2 1 B Trumpet / Cornet th nd 1 4 B Trombone 2 2 B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Baritone 2 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 2 4th B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Tuba 2 1st F & E Horn 2 2nd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Hot! Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Big Band Concert Band 1 Hot Samba (Noris) 2’51 EMR 11312 EMR 9113 EMR 14237 2 Hot Jive (Noris) 2’27 EMR 11655 EMR 9332 EMR 19813 3 Hot Mambo (Noris) 2’54 EMR 11789 EMR 9333 EMR 20504 4 Hot Merengue (Noris) 3’33 EMR 11798 -

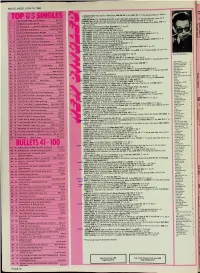

MUSIC WEEK JUNE 16, 1984 TOP IIS Singi 1* 1 TIMF AFTER TIME

MUSIC WEEK JUNE 16, 1984 A BIGGER SPLASH DONT BELIEVE A WORDISilcnce ABM AM 196 Pic Bag; AMX 196 1!" Pic Bag ii i track Don't Believe A IS * TOP IIS SiNGI ABMSWEWHEELS THE PRISONEfUCHRISTIANNE IDouble-fll Clay CLAY OTZCLAY 33 12" inc eatra track Black Icalher Girt IPI 1* 1 TIMF AFTER TIME. Cyndi Laupor Portrait . "ALMOND Marc THE BOY WHO CAME BACK/Jocy Demento Some BinareJPhonogrom BZS 2310 10" Pic Bag IH Capitol i-.v '•AND ALSO THE TREES THE SECRET SEA/There Were No Bounds/Tease The Tear/Midnight Garden/Wallpaper Dying Reflex 12 7* 4 tup bffi EX. Duran Duron only Pic Bag IliRT) 3 2 LET'S HEAR IT.... Denieca Williams Columbia/CBS ANDY. Horace CONFUSlONIIVersionl Music Hawk MHD 13 1? only US) ARRON HOT-HOT-HOT/llnst) Air/ChrYsalis ARROX 1 Pc Bag IF) 4 3 nu SHFRRIE. Steve Perry Columbia/CBS BELLE STARS 80's ROMANCBIfs Me Stiff BUY 200 Pic Bag ICI MCA • BIG COUNTRY HARVEST HQME/Balcony/Flag Of Nations ISwimmmgl MercurYlPhonogram COUNT 12 12 m 5 5 SISTER CHRISTIAN, Night Ranger BIG COUNTRY IN A BIG COUNTRY (THE PURE MIXllln A Big CountiY/All Of Us MercurYlPhonogram COUNT 312 U IN S* 6 THEHEARTOFROCK'N*ROLL.Huey Lewis Chrysalis ^Ei BIG COUNTRY CHANCE/The Tracks 01 My Tears/The Crossing MercurylPhonogram COUNT 412 12" IF) Atlantic BIG COUNTRY WONDERLAND IEXT VERSlONI/WonderlandlGiants MercurY/Phooogram COUNT 512 12" IF) 7* 9 SELF CONTROL, Laura Branigon BIG COUNTRY FIELDS OF FIRE lAHemative M.xJlFlELDS OF FIRE MOO MILESl/Angle Park MercurYlPhonogram COUNT 212 u in Planet BILK, Acker ACKER'S LUlLABYlOnc More Time PRT 7P 313 (A) 8* 10 JUMP IFOR MY LOVE). -

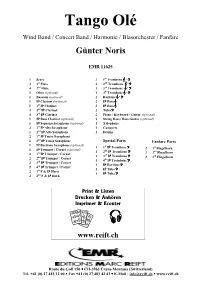

EMR 11625 Tango

Tango Olé Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Günter Noris EMR 11625 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd rd 4 2 Flute 1 3 Trombone + th 1 Oboe (optional) 1 4 Trombone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 E Bass st 5 1 B Clarinet 2 B Bass 4 2nd B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 3rd B Clarinet 2 Piano / Keyboard / Guitar (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 String Bass / Bass Guitar (optional) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 1 Xylophone 2 1st E Alto Saxophone 1 Castanets 1 2nd E Alto Saxophone 1 Drums st 2 1 B Tenor Saxophone nd 1 2 B Tenor Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) st 1 1 B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) nd 1 2 B Trombone nd 2 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 2 2 Flugelhorn 1 3rd B Trombone rd 2 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 2 3 Flugelhorn th rd 1 4 B Trombone 2 3 B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Baritone 2 4th B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 2 1st F & E Horn 1 B Tuba 2 2nd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Moonlight Magic Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Big Band Concert Band 1 Moonlight Magic (Noris) 3’26 EMR 11502 EMR 9267 EMR 19967 2 Jive And Jump (Noris) 2’40 EMR 11799 EMR 9425 EMR 20512 3 Rock Star (Noris) 3’02 EMR 11503 EMR 9426 EMR 19472 -

RCA Consolidated Series, Continued

RCA Discography Part 18 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Consolidated Series, Continued 2500 RCA Red Seal ARL 1 2501 – The Romantic Flute Volume 2 – Jean-Pierre Rampal [1977] (Doppler) Concerto In D Minor For 2 Flutes And Orchestra (With Andraìs Adorjaìn, Flute)/(Romberg) Concerto For Flute And Orchestra, Op. 17 2502 CPL 1 2503 – Chet Atkins Volume 1, A Legendary Performer – Chet Atkins [1977] Ain’tcha Tired of Makin’ Me Blue/I’ve Been Working on the Guitar/Barber Shop Rag/Chinatown, My Chinatown/Oh! By Jingo! Oh! By Gee!/Tiger Rag//Jitterbug Waltz/A Little Bit of Blues/How’s the World Treating You/Medley: In the Pines, Wildwood Flower, On Top of Old Smokey/Michelle/Chet’s Tune APL 1 2504 – A Legendary Performer – Jimmie Rodgers [1977] Sleep Baby Sleep/Blue Yodel #1 ("T" For Texas)/In The Jailhouse Now #2/Ben Dewberry's Final Run/You And My Old Guitar/Whippin' That Old T.B./T.B. Blues/Mule Skinner Blues (Blue Yodel #8)/Old Love Letters (Bring Memories Of You)/Home Call 2505-2509 (no information) APL 1 2510 – No Place to Fall – Steve Young [1978] No Place To Fall/Montgomery In The Rain/Dreamer/Always Loving You/Drift Away/Seven Bridges Road/I Closed My Heart's Door/Don't Think Twice, It's All Right/I Can't Sleep/I've Got The Same Old Blues 2511-2514 (no information) Grunt DXL 1 2515 – Earth – Jefferson Starship [1978] Love Too Good/Count On Me/Take Your Time/Crazy Feelin'/Crazy Feeling/Skateboard/Fire/Show Yourself/Runaway/All Nite Long/All Night Long APL 1 2516 – East Bound and Down – Jerry -

Using a Jive Community Notices

Cloud User Guide Using a Jive Community Notices Notices For details, see the following topics: • Notices • Third-party acknowledgments Notices Copyright © 2000±2021. Aurea Software, Inc. (ªAureaº). All Rights Reserved. These materials and all Aurea products are copyrighted and all rights are reserved by Aurea. This document is proprietary and confidential to Aurea and is available only under a valid non-disclosure agreement. No part of this document may be disclosed in any manner to a third party without the prior written consent of Aurea.The information in these materials is for informational purposes only and Aurea assumes no respon- sibility for any errors that may appear therein. Aurea reserves the right to revise this information and to make changes from time to time to the content hereof without obligation of Aurea to notify any person of such revisions or changes. You are hereby placed on notice that the software, its related technology and services may be covered by one or more United States (ªUSº) and non-US patents. A listing that associates patented and patent-pending products included in the software, software updates, their related technology and services with one or more patent numbers is available for you and the general public's access at https://markings.ip- dynamics.ai/esw/ (the ªPatent Noticeº) without charge. The association of products- to-patent numbers at the Patent Notice may not be an exclusive listing of associa- tions, and other unlisted patents or pending patents may also be associated with the products. Likewise, the patents or pending patents may also be associated with unlisted products. -

M. Shulman, the American Pipe Dream, Dissertation

The American Pipe Dream: Drug Addiction on Stage, 1890-1940 A dissertation submitted by MAX SHULMAN In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama Tufts University May 2016 Copyright © 2016, Max Shulman Adviser: Dr. Laurence Senelick ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the representation of drug addiction and drug use in U.S. theatre from the 1890s to the start of the Second World War. In this, it engages with the decades in which the nation first formulated its conceptions of addiction. It is in the 1890s that addicts first appear on stage and assume a significant place in the national imaginary. Over the next fifty years, the theatre becomes an integral part of a cultural process that shapes the characterization, treatment, and legislative paradigms regarding addiction. In many cases, these paradigms that appear during the Progressive Era, Jazz Age, and Depression persist today. This study examines this history by looking at a variety of performance formats, including melodrama, vaudeville, and Jazz club acts. Ranging from the “elite” theatres of Broadway to the “lowbrow” variety stages, this research establishes connections between representational practice and an array of sources. These include the medical, legal, and literary histories related to drug use in the period. Up till now, these are the histories that scholars have recorded, but they have yet to take into account the importance of performance as it both formed and reflected other elements of culture related to drug use. It was the stage that helped push through reforms on part of the Prohibition Era activists; it was also the stage that disseminated the rapidly changing medical etiologies of addiction to the general populace. -

Jazz on a Winter's Day… the Chicken Fat Ball!

Volume 46 • Issue 2 february 2018 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. The Chicken Fat Ball presented another outstanding band on January 7. On stage at The Woodland in Maplewood were (l-r): Conal Fowkes, Nicki Parrott, Adrian Cunningham, Paul Wells, Randy Sandke, Randy Reinhart and John Allred. Photo by Lynn Redmile. Jazz On a Winter’s Day… The Chicken Fat Ball! Once again Chicken Fat Ball organizers Al Kuehn and Don Greenfield reeled in a full house of loyal jazz fans to The Woodland in Maplewood for a swinging three-hour musical feast that warmed a cold January day. Jersey Jazz was there and brings you the story and Lynn Redmile’s pictures beginning on page 26. THE 49th ANUAL PEE WEE RUSSELL MEMORIAL STOMP March 18 at The Birchwood Manor/Mitchell Seidel’s preview is on page 24 New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: New Jersey Jazz socIety Prez Sez . 2 Bulletin Board . 2 NJJS Calendar . 3 Jazz Trivia . 4 Prez sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 Change of Address/Support NJJS/ By Cydney Halpin President, NJJS Volunteer/Join NJJs . 47 Crow’s Nest . 48 t is with great enthusiasm that I write my first Fuller. His time and attention to these special New/Renewed Members . 49 IPrez Sez column as the newly-elected president presentations really added depth and detail to storIes of the New Jersey Jazz Society. I am looking this historical event and we thank Stephen for a Chicken Fat Ball . cover forward to working with the rest of the new job well done. -

EMR 3070 Swing and Jive BB

Swing And Jive Brass Band Arr.: Bertrand Moren Günter Noris EMR 3070 st 1 Full Score 2 1 B Trombone + nd 1 E Cornet 2 2 B Trombone + st 3 1 Solo B Cornet 1 Bass Trombone + 3 2nd Solo B Cornet 2 Euphonium 1 Repiano Cornet 3 E Bass 3 2nd B Cornet 3 B Bass 3 3rd B Cornet 1 Piano / Keyboard / Guitar (optional) 1 B Flugelhorn 1 Bass Guitar (optional) 2 Solo E Horn 1 Bongos 2 1st E Horn 1 Drum Set 2 2nd E Horn 2 1st B Baritone 2 2nd B Baritone Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Feel Like Dancing Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Big Band Concert Band 1 Feel Like Dancing (Noris) 2’45 EMR 10521 EMR 3062 EMR 13079 2 Charleston Darling (Noris) 2’33 EMR 10514 EMR 3067 EMR 13084 3 Cha Cha Mirage (Noris) 3’08 EMR 11298 EMR 3904 EMR 14224 4 Melancholy Waltz (Noris) 3’21 EMR 11262 EMR 3905 EMR 13883 5 Puppy Foxtrot (Noris) 3’01 EMR 11302 EMR 3906 EMR 14228 6 Let’s Do The Jive (Noris) 2’30 EMR 1842 EMR 2552 EMR 13810 7 Time To Tango (Noris) 2’55 EMR 11267 EMR 3907 EMR 14167 8 Get Up And Swing (Noris) 3’14 EMR 10099 EMR 2883 EMR 13832 9 Swing And Jive (Noris) 2’50 EMR 10510 EMR 3070 EMR 13087 10 Venus Waltz (Noris) 3’00 EMR 11294 EMR 3908 EMR 14181 11 Twisting Saxophones (Noris) 2’11 EMR 10523 EMR 3074 EMR 13091 12 Cheerful Cha Cha (Noris) 3’03 EMR 11258 EMR 3909 EMR 13887 13 Dancing Clown (Noris) 2’29 EMR 10518 EMR 3065 EMR 13082 14 Jumpin’ Jive (Noris) 2’24 EMR 11261 EMR 3910 EMR 13886 Zu bestellen bei • A commander chez • To be ordered from: Editions Marc Reift • Route du Golf 150 • CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) • Tel. -

Konzert, Mittwoch, 6. N Ovember 2019

a r t s & co n c e r t s HA U S 1 9 www.7hours.com| [email protected] 7hours office Christiane Grüß; Kaiser-Friedrich-Str. 27, D-10585 Berlin | T +49 (0) 30 3435 9664 | Cell 0177 3051 761 KONZERT, MITTWOCH, 6. NOVEMBER 2019: BIOGRAFISCHE ANGABEN MICHAEL PARSONS (experimentalmusic.co.uk/wp/emc-composers/michael-parsons/) (b. 1938, Bolton) studied at St John’s College, Oxford and then the Royal College of Music with Peter Racine Fricker. As a music critic he wrote insightful reviews for the New Left Journal and the Financial Times. He met Cornelius Cardew in the mid-1960s and, with Cardew and Howard Skempton, founded the Scratch Orchestra (1969–73). Parsons taught at the Portsmouth College of Art, where he became part of the musical faction of the British Systems Art movement (other composers including John White and Christopher Hobbs), and Slade School of Art. He performed in percussion and other duos with Howard Skempton, and for years has run concert series and workshops for the London Musicians’ Collective, Kettle’s Yard, and elsewhere. Parsons’ compositional style reflects his interest in experimental music and systems, plus his early influences of Webern, Feldman, Cage, and Cardew. He has written a full experimental opera and a related choir piece, Expedition to the North Pole, and a series of piano pieces. Parsons has also written pieces with folk and popular influences, including ragtime and Macedonian pieces. ProfileOne of the founding members of the Scratch Orchestra, Michael Parsons (b. 1938) has been not only an important composer, but also a writer, critic, and director of workshops and concerts of experimental and minimalist/systemic music in Britain since the 1960s. -

Graph Drawing in Education

24 Graph Drawing in Education 24.1 Introduction::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 737 24.2 Applications::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 738 Algorithm Animation • Algorithm Simulation • Exercise Systems • Exploration Systems • Program Visualization • Software Visualization 24.3 Graph Drawing for Algorithm Animation :::::::::::::: 744 A Unified Approach to Drawing Data Structures • Special-Purpose Layouts 24.4 Graph Drawing for Program Visualization ::::::::::::: 747 Complex Node Structures • Taking Structure into Account • Drawing Execution Environments • Drawing Sequence Diagrams 24.5 Graph Drawing for Software Visualization ::::::::::::: 750 Drawing UML Class Diagrams 24.6 Sequences of Drawings::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 752 Trees • Force-Directed Layout • Sugiyama-Style Hierarchical Stina Bridgeman Layout • Offline Dynamic Graph Drawing • Smooth Hobart and William Smith Animation Colleges References :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 757 24.1 Introduction Illustrations are a powerful explanatory tool, so one might expect a long history of the use of graph drawing in education. This history can be traced back to at least the Middle Ages, where squares of opposition (Figure 24.1) were used as pedagogical tools in logic and other fields [KMBW02]. Murdoch [Mur84] provides examples of both basic squares and more complex structures. In mathematics, drawings of abstract graphs began to appear as illustrations in the late 18th century, 150 years after Euler's famous paper on the K¨onigsberg bridges launched the field of graph theory [KMBW02]. Now commonplace, hand-drawn pictures of small graphs are often used as illustrations in math and computer science textbooks to describe a graph-related concept or to explain a graph algorithm|any graph theory, discrete math, or data structures text will contain many such pictures. Drawings of graphs are also used to illustrate graph-structured information, such as the topology of a computer network or a flow chart showing a program's execution. -

Community Administration Notices

Cloud Administrator Guide Community Administration Notices Notices For details, see the following topics: • Notices • Third-party acknowledgments Notices Copyright © 2000±2021. Aurea Software, Inc. (ªAureaº). All Rights Reserved. These materials and all Aurea products are copyrighted and all rights are reserved by Aurea. This document is proprietary and confidential to Aurea and is available only under a valid non-disclosure agreement. No part of this document may be disclosed in any manner to a third party without the prior written consent of Aurea.The information in these materials is for informational purposes only and Aurea assumes no respon- sibility for any errors that may appear therein. Aurea reserves the right to revise this information and to make changes from time to time to the content hereof without obligation of Aurea to notify any person of such revisions or changes. You are hereby placed on notice that the software, its related technology and services may be covered by one or more United States (ªUSº) and non-US patents. A listing that associates patented and patent-pending products included in the software, software updates, their related technology and services with one or more patent numbers is available for you and the general public's access at https://markings.ip- dynamics.ai/esw/ (the ªPatent Noticeº) without charge. The association of products- to-patent numbers at the Patent Notice may not be an exclusive listing of associa- tions, and other unlisted patents or pending patents may also be associated with the products. Likewise, the patents or pending patents may also be associated with unlisted products. -

5204 Songs, 13.5 Days, 35.10 GB

Page 1 of 158 Music 5204 songs, 13.5 days, 35.10 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I'm All the Way Up 3:12 I'm All the Way Up - Single Dj LaserJet 2 NozeBleedz (feat. Ripp Flamez) 2:39 NozeBleedz (feat. Ripp Flamez)… Ray Jr. 3 All of Me 3:04 The Piano Guys 2 The Piano Guys 4 All of Me 3:03 The Piano Guys 2 (Deluxe Edition) The Piano Guys 5 Three Times a Lady 3:41 Encore - Live at Wembley Arena Lionel Richie 6 The Way You Look Tonight 3:22 Nothing But the Best (Remaster… Frank Sinatra 7 Every Time I Close My Eyes 4:57 A Collection of His Greatest Hits Babyface, Mariah Carey, Kenny… 8 2U (feat. Justin Bieber) 3:15 2U (feat. Justin Bieber) - Single David Guetta 9 A Mother's Day 3:55 Simple Things Jim Brickman 10 Mean To Me 3:49 Bring You Back Brett Eldredge 11 Anywhere 4:04 Room 112 112 12 Don't Drop That Thun Thun 3:22 Don't Drop That Thun Thun - Sin… Finatticz 13 With You 4:12 Exclusive (The Forever Edition) Chris Brown 14 Like Jesus Does 3:19 Chief Eric Church 15 Nice & Slow 3:48 My Way Usher 16 Broccoli (feat. Lil Yachty) 3:45 Broccoli (feat. Lil Yachty) - Single DRAM 17 Grow Old With Me 3:09 Milk and Honey John Lennon 18 When I'm Holding You Tight (Re… 4:10 MSB (Remastered) Michael Stanley Band 19 Hot for Teacher 4:43 1984 Van Halen 20 Death of a Bachelor 3:24 Death Of A Bachelor Panic! At the Disco 21 Family Tradition 4:00 Hank Williams, Jr.'s Greatest Hit… Hank Williams, Jr.