FROM PAUL to PENNY: the EMERGENCE and DEVELOPMENT of TSONGA DISCO 1985-1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Too Late for Mama” Lyrics by Brenda Fassie (South Africa)

“Too Late For Mama” Lyrics By Brenda Fassie (South Africa) Verse 1 Ten kilometers barefooted in the bush Started raining on the way to fetch some water Poor woman had a baby on her back Was struck by lightning on her way To fetch some water... She tried hiding under a tree to save her child Poor woman had no place to go Lightning caught her with her baby on her back Friends, relatives ran for her Ten kilometres barefooted in But it was too late the bush It was too late... too late for mama Husband came running to the scene yeah, Started raining Poor man held his dead wife in his arms, on the way to fetch some Eyes full of tears not believing the nightmare, Knelt down and prayed for this was a painful loss water Chorus Too late... too late for mama Oh mama mama, poor mama, It was too late... too late Verse 2 She tried hiding under a tree to save her child Poor woman had no place to hide Lightning caught her with her baby on her back Friends, relatives ran for her Chorus But it was too late (mama) Too late for mama (mama) Too late (mama) Too late for mama (mama) Oh mama mama (mama) Oh poor mama (mama) It was too late (mama) Too late for mama (mama) Oh mama (mama) Mama with her little baby (mama) She’s gone (mama) It was too late (mama) She’s gone (mama) Oh poor mama (mama) Too late for mama Too late! Too late! Too late! (mama) (mama) Too late for mama Oh mama (mama) Too late for mama Too late! Too late! Oh mama mama My poor mama It was too late It was too late Mama with her little baby (mama) She’s gone (mama) She’s gone (mama) My mama mama My poor mama .. -

EMR 11655 Hot Jive

Hot Jive Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Günter Noris EMR 11655 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd rd 4 2 Flute 1 3 Trombone + th 1 Oboe (optional) 1 4 Trombone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 E Bass st 5 1 B Clarinet 2 B Bass 4 2nd B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 3rd B Clarinet 2 Piano / Keyboard / Guitar (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 String Bass / Bass Guitar (optional) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 1 Congas 2 1st E Alto Saxophone 1 Drums nd 1 2 E Alto Saxophone st 2 1 B Tenor Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts nd 1 2 B Tenor Saxophone st 1 1 B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) nd 1 2 B Trombone nd 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 2 2 Flugelhorn rd rd st 1 3 B Trombone 2 3 Flugelhorn 2 1 B Trumpet / Cornet th nd 1 4 B Trombone 2 2 B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Baritone 2 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 2 4th B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Tuba 2 1st F & E Horn 2 2nd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Hot! Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Big Band Concert Band 1 Hot Samba (Noris) 2’51 EMR 11312 EMR 9113 EMR 14237 2 Hot Jive (Noris) 2’27 EMR 11655 EMR 9332 EMR 19813 3 Hot Mambo (Noris) 2’54 EMR 11789 EMR 9333 EMR 20504 4 Hot Merengue (Noris) 3’33 EMR 11798 -

Music of Politics and Religion Supporting Constitutional Values in South Africa

Article Music of Politics and Religion Supporting Constitutional Values in South Africa Morakeng E.K. Lebaka University of South Africa [email protected] Abstract The Constitution of South Africa has been taken as a model globally as it supports non-discrimination and human rights. The purpose of this study was to analyse the South African National Anthem and a secular political song to investigate how music supported the values enshrined in the Constitution, including religious freedom, during the transition from a history of apartheid towards 25 years of democracy. Politicians such as Nelson Mandela and religious leaders such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu, black African spiritual practitioners, Muslim ecclesiastics, rabbis and others played a prominent role in a peaceful transition to democracy. Although there have been a few violent episodes like service delivery protests, farm murders, xenophobia and the tragedy of Marikana since 1994, in general South Africa has been peaceful, despite its history. This study concluded that the music of politics and liberation can be related to value systems and lack of conflict between ethnic and religious factions in South Africa since 1994. Keywords: South African Constitution; South African Anthem; struggle songs; reconciliation Introduction and Literature Review In 1994 South Africa transformed itself into a peaceful democracy without a civil war. Our neighbours—Mozambique, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Angola—all went to war to achieve peace. South African Special Forces played a pivotal role in the South African Border War and were active alongside the Rhodesian Security forces during the Rhodesian Bush War (Scholtz 2013). Combat operations were also undertaken against FRELIMO militants in Mozambique (Harry 1996, 13-281). -

2014 Edition

Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy The Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy does not accept responsibility for the views expressed by individual authors. No part of the publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the expressed written consent of the editors of the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy. © 2014 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. Except as otherwise specified, no article or portion herein is to be reproduced or adapted to other works without the expressed written consent of the editors of the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy. ii Support the Journal The Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy (ISSN# 1081-0463) is a student- run journal published annually at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. An annual subscription is $10 for students, $10 for individuals, and $40 for libraries and institutions. Additional copies of Volumes I–XVI may be available for $10 each from the Subscriptions Department, Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy, 79 JFK Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. Donations provided in support of the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy are tax deductible as a nonprofit gift under the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University’s IRS 501(c) (3) status. Please specify intent. Send address changes to: Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Or by e-mail to: [email protected] iii Acknowledgements The editorial board of the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy would like to thank the following individuals for their generous support and contributions to the publication of this issue: Richard Parker, Faculty Advisor Martha Foley, Publisher Pamela Ardila, Copy Editor Yiqing Shao, Graphic Designer David Ellwood, Dean of the John F. -

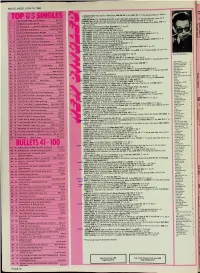

MUSIC WEEK JUNE 16, 1984 TOP IIS Singi 1* 1 TIMF AFTER TIME

MUSIC WEEK JUNE 16, 1984 A BIGGER SPLASH DONT BELIEVE A WORDISilcnce ABM AM 196 Pic Bag; AMX 196 1!" Pic Bag ii i track Don't Believe A IS * TOP IIS SiNGI ABMSWEWHEELS THE PRISONEfUCHRISTIANNE IDouble-fll Clay CLAY OTZCLAY 33 12" inc eatra track Black Icalher Girt IPI 1* 1 TIMF AFTER TIME. Cyndi Laupor Portrait . "ALMOND Marc THE BOY WHO CAME BACK/Jocy Demento Some BinareJPhonogrom BZS 2310 10" Pic Bag IH Capitol i-.v '•AND ALSO THE TREES THE SECRET SEA/There Were No Bounds/Tease The Tear/Midnight Garden/Wallpaper Dying Reflex 12 7* 4 tup bffi EX. Duran Duron only Pic Bag IliRT) 3 2 LET'S HEAR IT.... Denieca Williams Columbia/CBS ANDY. Horace CONFUSlONIIVersionl Music Hawk MHD 13 1? only US) ARRON HOT-HOT-HOT/llnst) Air/ChrYsalis ARROX 1 Pc Bag IF) 4 3 nu SHFRRIE. Steve Perry Columbia/CBS BELLE STARS 80's ROMANCBIfs Me Stiff BUY 200 Pic Bag ICI MCA • BIG COUNTRY HARVEST HQME/Balcony/Flag Of Nations ISwimmmgl MercurYlPhonogram COUNT 12 12 m 5 5 SISTER CHRISTIAN, Night Ranger BIG COUNTRY IN A BIG COUNTRY (THE PURE MIXllln A Big CountiY/All Of Us MercurYlPhonogram COUNT 312 U IN S* 6 THEHEARTOFROCK'N*ROLL.Huey Lewis Chrysalis ^Ei BIG COUNTRY CHANCE/The Tracks 01 My Tears/The Crossing MercurylPhonogram COUNT 412 12" IF) Atlantic BIG COUNTRY WONDERLAND IEXT VERSlONI/WonderlandlGiants MercurY/Phooogram COUNT 512 12" IF) 7* 9 SELF CONTROL, Laura Branigon BIG COUNTRY FIELDS OF FIRE lAHemative M.xJlFlELDS OF FIRE MOO MILESl/Angle Park MercurYlPhonogram COUNT 212 u in Planet BILK, Acker ACKER'S LUlLABYlOnc More Time PRT 7P 313 (A) 8* 10 JUMP IFOR MY LOVE). -

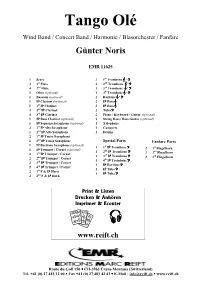

EMR 11625 Tango

Tango Olé Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Günter Noris EMR 11625 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd rd 4 2 Flute 1 3 Trombone + th 1 Oboe (optional) 1 4 Trombone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 E Bass st 5 1 B Clarinet 2 B Bass 4 2nd B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 3rd B Clarinet 2 Piano / Keyboard / Guitar (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 String Bass / Bass Guitar (optional) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 1 Xylophone 2 1st E Alto Saxophone 1 Castanets 1 2nd E Alto Saxophone 1 Drums st 2 1 B Tenor Saxophone nd 1 2 B Tenor Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) st 1 1 B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) nd 1 2 B Trombone nd 2 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 2 2 Flugelhorn 1 3rd B Trombone rd 2 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 2 3 Flugelhorn th rd 1 4 B Trombone 2 3 B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Baritone 2 4th B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 2 1st F & E Horn 1 B Tuba 2 2nd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Moonlight Magic Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Big Band Concert Band 1 Moonlight Magic (Noris) 3’26 EMR 11502 EMR 9267 EMR 19967 2 Jive And Jump (Noris) 2’40 EMR 11799 EMR 9425 EMR 20512 3 Rock Star (Noris) 3’02 EMR 11503 EMR 9426 EMR 19472 -

Amandla: a Revolution in Four Part Harmony 2002 Complete Music

Amandla: A Revolution in Four Part Harmony 2002 Complete Music Numbered entries are from the sound tract CD. Additional, unnumbered items are from the end credits for the movie. Toyi Toyi Chant 1 AMANDLA! Protest meeting, Johannesburg 2 When You Come Back Vusi Mahlasela Ntsi Kana’s Bell Abdullah Ibrahim, also Hugh Masakela 3 Lizobuya Mbongeni Ngema 4 Meadowlands Nancy Jacobs and sisters 5 Sad Times, Bad Times The Original Cast of King Kong 6 Senzeni Na? Vusi Mahlasela & Harmonious Serenade Choir 7 Beware Verwoerd (Naants’ Indod’ Emnyama) Miriam Makeba Into Yam Miriam Makeba 8 Y’zinga Robben-Island Prison Singers Come Outro Zwai Bala and TK Zee (performers) 9 Stimela Hugh Masekela Maraba Blue Abdullah Ibrahim 10 Injamblo/Hambani Kunye Ne – Vangeli Pretoria Central Prison Makeba Miriam Makeba 11 Manneberg Abdullah Ibrahim 12 Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika Soweto Community Hall 13 Thina Lomhlaba Siwugezi Vusi Mahlasela Palafala (Midnight Lover Mix) Zwai Bala and TK Zee (performers) 14 Mayibuye Vusi Mahlasela Madame Please Sophie Mgcina (performer) 15 Thina Sizwe SABC Choir Golomenda Zenzenia 16 Folk Vibe # 1 Tananas Lihambile Hamba Kahle Lindiwe Zulu (performer) 17 Dabula Ngesi'bam Soweto Community Hall 18 Sobahiya Abazali Ekhaya Amandla Group (performers) Thina Sengenange Jambo Militants (performers) 19 Bring Him Back Home (Nelson Mandela) Hugh Masekela Sign On Radio Freedom (performers) 20 Did You Hear That Sound? (Dreamtime Improv) Abdullah Ibrahim AK 47 Radio Freedom 21 S'bali Joe Nina Red Song Vusi Mahlasela 22 Makuliwe Soweto Community Hall -

Market Theatre Foundation

27 October - 10 October 2019 1 Page 5 Editor’s Note Page 6 Hard Work Pays Off, A Doctorate Conferred On Ismail Mahomed Page 8 ABRIDGED VERSION OF KEYNOTE ADDRESS DELIVERED BY ISMAIL MAHOMED Page 12 Excellence Rewarded At The Inaugural Afro-Tech Art Award Page 14 30 years of Market Photo Workshop Page 16 Moussa John Kalapo Other Worlds Book Launch Page 18 Scenes From Reframing Africa Page 20 Eugène Ionesco’s Rhinoceros Travels To Cape Town Windybrow Arts Centre Page 22 Celebrates Zambian Independence Day Page 24 Ub’dope Shishini Residency Soaring To Great Heights Page 26 A Six Week Festival To Celebrate 30 Years Page 28 The Storyteller of Riverlea is back for its second homecoming at the Market Theatre 2 MARKET BUZZ Volume 3 No 09 27 October - 10 October 2019 1 Page 30 Mandla Mlangeni Live at the THE MARKET BUZZ Market Theatre TEAM Page 32 Where Are They Now? WRITERS: Clara Vaughan (Market Laboratory Head) Ismail Mahomed (Market Theatre Foundation CEO) WHAT’S ON AT THE Page 34 Keitu Gwangwa MARKET THEATRE (Windybrow Arts Centre Head) FOUNDATION Khona Dlamini (Programmes and Project Manager) Candice Jansen (Research & Exhibitions Programming Manager) Page 39 Scene at the Market Theatre Cebisile Mbonambi (MPW Social Media Intern Lusanda Zokufa-Kathilu (Senior Publicist) Zama Sweetness Buthelezi (Brand and Communications Manager) Zodwa Shongwe (Producer) Thozama Busakwe (Market Laboratory Marketing The Market Theatre Foundation is an agency of the Assistant) Department of Arts & Culture STORY RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT: Lusanda Zokufa-Kathilu -

RCA Consolidated Series, Continued

RCA Discography Part 18 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Consolidated Series, Continued 2500 RCA Red Seal ARL 1 2501 – The Romantic Flute Volume 2 – Jean-Pierre Rampal [1977] (Doppler) Concerto In D Minor For 2 Flutes And Orchestra (With Andraìs Adorjaìn, Flute)/(Romberg) Concerto For Flute And Orchestra, Op. 17 2502 CPL 1 2503 – Chet Atkins Volume 1, A Legendary Performer – Chet Atkins [1977] Ain’tcha Tired of Makin’ Me Blue/I’ve Been Working on the Guitar/Barber Shop Rag/Chinatown, My Chinatown/Oh! By Jingo! Oh! By Gee!/Tiger Rag//Jitterbug Waltz/A Little Bit of Blues/How’s the World Treating You/Medley: In the Pines, Wildwood Flower, On Top of Old Smokey/Michelle/Chet’s Tune APL 1 2504 – A Legendary Performer – Jimmie Rodgers [1977] Sleep Baby Sleep/Blue Yodel #1 ("T" For Texas)/In The Jailhouse Now #2/Ben Dewberry's Final Run/You And My Old Guitar/Whippin' That Old T.B./T.B. Blues/Mule Skinner Blues (Blue Yodel #8)/Old Love Letters (Bring Memories Of You)/Home Call 2505-2509 (no information) APL 1 2510 – No Place to Fall – Steve Young [1978] No Place To Fall/Montgomery In The Rain/Dreamer/Always Loving You/Drift Away/Seven Bridges Road/I Closed My Heart's Door/Don't Think Twice, It's All Right/I Can't Sleep/I've Got The Same Old Blues 2511-2514 (no information) Grunt DXL 1 2515 – Earth – Jefferson Starship [1978] Love Too Good/Count On Me/Take Your Time/Crazy Feelin'/Crazy Feeling/Skateboard/Fire/Show Yourself/Runaway/All Nite Long/All Night Long APL 1 2516 – East Bound and Down – Jerry -

South African Music in Global Context

South African Music in Global Perspective Gavin Steingo Assistant Professor of Music University of Pittsburgh South African Music * South African music is a music of interaction, encounter, and circulation * South African music is constituted or formed through its relations to other parts of the world * South African music is a global music (although not evenly global – it has connected to different parts of the world at different times and in different ways) Pre-Colonial South African Music * Mainly vocal * Very little drumming * Antiphonal (call-and-response) with parts overlapping * Few obvious cadential points * Partially improvisatory * “Highly organized unaccompanied dance song” (Coplan) * Instruments: single-string bowed or struck instruments, reed pipes * Usually tied to social function, such as wedding or conflict resolution Example 1: Zulu Vocal Music Listen for: * Call-and-Response texture * Staggered entrance of voices * Ending of phrases (they never seem very “complete”) * Subtle improvisatory variations Example 2: Musical Bow (ugubhu) South African History * 1652 – Dutch settle in Cape Town * 1806 – British annex Cape Colony * 1830s – Great Trek * 1867 – Discovery of diamonds * 1886 –Discovery of gold * 1910 – Union of South Africa * 1913 – Natives’ Land Act (“natives” could only own certain parts of the country) * 1948 – Apartheid formed * Grand apartheid (political) * Petty apartheid (social) * 1990 – Mandela released * 1994 – Democratic elections Early Colonial History: The Cape of Good Hope Cape Town * Dutch East India Company -

Using a Jive Community Notices

Cloud User Guide Using a Jive Community Notices Notices For details, see the following topics: • Notices • Third-party acknowledgments Notices Copyright © 2000±2021. Aurea Software, Inc. (ªAureaº). All Rights Reserved. These materials and all Aurea products are copyrighted and all rights are reserved by Aurea. This document is proprietary and confidential to Aurea and is available only under a valid non-disclosure agreement. No part of this document may be disclosed in any manner to a third party without the prior written consent of Aurea.The information in these materials is for informational purposes only and Aurea assumes no respon- sibility for any errors that may appear therein. Aurea reserves the right to revise this information and to make changes from time to time to the content hereof without obligation of Aurea to notify any person of such revisions or changes. You are hereby placed on notice that the software, its related technology and services may be covered by one or more United States (ªUSº) and non-US patents. A listing that associates patented and patent-pending products included in the software, software updates, their related technology and services with one or more patent numbers is available for you and the general public's access at https://markings.ip- dynamics.ai/esw/ (the ªPatent Noticeº) without charge. The association of products- to-patent numbers at the Patent Notice may not be an exclusive listing of associa- tions, and other unlisted patents or pending patents may also be associated with the products. Likewise, the patents or pending patents may also be associated with unlisted products. -

1 (1 .. . Es * ,. 1* 5, .1

(1 (1 .. es * ,. 1* 5, .1 - SI . 1. *, 444 -- 5*~ j II 1 'U New Books from Ravan Press GOLD AND WORKERS -A People's History of South Africa Volume 1 %s Vby Luli Callinicos 'Veryinterestingtous,the workers. It gives abackgroundto labourrelationsiv when industrial mining began.' Moses Mayekiso, Transvaal Branch Secretary of Metal and Allied Workers Union. 'It is extremely well researched . It aims to set up the black workers who have underpinned our industrial economy as unsung heroes who have borne the heat of the day (or rather the depths) so that the economy, from which whites have been the chief beneficiaries, could prosper, 'It is rich enough in ideas and stimulating enough in content to serve as a source book for classes throughout the land.' - Prof. T R H Davenport , History Department, Rhodes University. WORKING FOR BOROKO THE ORIGINS OF A COERCIVE LABOUR SYSTEM IN SOUTH AFRICA by Marian Lacey 'Working for nothing, for a place to sleep.' A searching new history which analyses the relationship between segregationist land policies and labour systems under successive South African governments. LOOKING THROUGH THE KEYHOLE by Noel Manganyi Further essays on black culture and experience by the author of BeingBlack-In-The-World and Mashangu's Reverie. The collection includes the text of a long interview between the author and Professor Es'kia Mphahlele. THE SCHOOL MASTER by Rose Moss A powerful and challenging new novel set in contemporary South Africa, which tells the story of the struggle of a humane young South African to resist the complicity of his unwilling collaboration in the daily practice of apartheid.