Women, Crime and Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Hall's Delicensing Scheme Revamped

LTDA The newspaper of the Licensed Taxi Drivers’ Association www.ltda.co.uk @TheLTDA BANK JUNCTION: p6 #435 22 January 2019 ACCESS BACK ON THE AGENDA p5 p2 Have-a- go hero tackles robber p31 MEMBERS BACK City Hall’s LTDA POLICY Delicensing Scheme Revamped Taxi Age Limit Cut Plan Get £10k for your 13-year-old“Unacceptabl cabe” TfL wipes £150m o p3 cab values overnight 2 TAXI |||| 22 January 2019 www.ltda.co.uk |||| @TheLTDA Cabbie Strikes Back Against Robbers NEWS IN BRIEF Plying for PEOPLE he would have got away otherwise.” hire PHV A brave taxi driver has struck It emerged that crook had back against the robbers earlier been involved in a driver fined making the lives of fellow robbery and has since appeared A private hire driver has been cabbies a misery by bringing in court on several charges. fined more than £1,000 after being one to justice. The west London area, caught illegally plying for hire in Richard Barrow, of Maida particularly around Lisson Reading. Khawaja Babar, 39, of Vale, sprang into action to help Grove, has become virtually Holberton Road in Reading – a a police officer being over- a no-go area for taxi drivers licensed minicab cab driver for powered by the thief, who had after a sharp rise in the number South Oxfordshire – was parked in been in the back of the 57-year- of robberies and distraction a bus stop outside a fast food shop old’s cab. thefts. in Friar Street, Reading, in the Both Mr Barrow and the In November, several taxi early hours of March 17, 2018. -

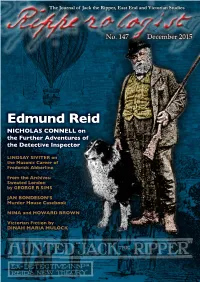

Edmund Reid NICHOLAS CONNELL on the Further Adventures of the Detective Inspector

No. 147 December 2015 Edmund Reid NICHOLAS CONNELL on the Further Adventures of the Detective Inspector LINDSAY SIVITER on the Masonic Career of Frederick Abberline From the Archives: Sweated London by GEORGE R SIMS JAN BONDESON’S Murder House Casebook NINA and HOWARD BROWN Victorian Fiction by DINAH MARIA MULOCK Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Quote for the month “Seriously I am amazed at some people who think a Pantomime of Jack the Ripper is okay. A play by all means but a pantomime? He was supposed to have cut women open from throat to thigh removed organs also laid them out for all to see. If that’s okay as a pantomime then lets have a Fred West pantomime or a Yorkshire Ripper show.” Norfolk Daily Press reader Brian Potter comments on reports of a local production. Sing-a-long songs include “Thrash Me Thrash Me”. Ripperologist 147 December 2015 EDITORIAL: THE ANNIVERSARY WALTZ EXECUTIVE EDITOR by Adam Wood Adam Wood EDITORS THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF Gareth Williams DETECTIVE INSPECTOR EDMUND REID Eduardo Zinna by Nicholas Connell REVIEWS EDITOR BROTHER ABBERLINE AND Paul Begg A FEW OTHER FELLOW NOTABLE FREEMASONS by Lindsay Siviter EDITOR-AT-LARGE Christopher T George JTR FORUMS: A DECADE OF DEDICATION COLUMNISTS by Howard Brown Nina and Howard Brown David Green FROM THE ARCHIVES: The Gentle Author SWEATED LONDON BY GEORGE R SIMS From Living London Vol 1 (1901) ARTWORK Adam Wood FROM THE CASEBOOKS OF A MURDER HOUSE DETECTIVE: MURDER HOUSES OF RAMSGATE Follow the latest news at by Jan Bondeson www.facebook.com/ripperologist A FATAL AFFINITY: CHAPTERS 5 & 6 Ripperologist magazine is free of charge. -

The Story of Jack the Ripper a Paradox

The Story of Jack the Ripper A Paradox 12/9/2012 1 The Story of Jack the Ripper - a Paradox is © copyright protected to the Author 2012. No part thereof may be copied, stored, or transmitted either electronically or mechanically without the prior written permission of the author. Mr Richard.A.Patterson. Emails can be sent to the author at, [email protected]. Further resources can be found at the author’s homepage at, http://www.richard-a-patterson.com/ Readers are welcome to view other texts by the author at, http://richardapatterson17.blogspot.com/ ISBN 0-9578625-7-1 CONTENTS Preface. A Ghost Story. Introduction. Murders in the Sanctuary. Chapter One Francis Thompson Poet of Sacrifice. Chapter Two Mary Ann Nichols - Innocent in Death. Chapter Three Annie Chapman a Remedy of Steel. Chapter Four Elizabeth Stride & Catherine Eddowes; ‘My Two Ladies.’ Chapter Five Mary Kelly and the Secret in Her Eyes. Chapter Six Francis Thompson, Confessions at Midnight. Chapter Seven The Demon Haunted World. Appendix. Bibliography. Printed in A4 size with Times New Roman, and Lucida Calligraphy fonts. Of about 125 thousand words. Please Read: Although fiction, much of this text is a reconstruction of events and often only rests on witness testimonies or newspaper reports. Much of the evidence has long since been destroyed by the forces of history. For sake of expediency, when there are conflicting witnesses the author has chosen to include material namely from city and metropolitan police. For aesthetic, this book does not fully cite its sources though the author hopes little within is made up and only veritable versions are included. -

JACK the RIPPER (The Whitechapel Murders) VICTIMS

JACK THE RIPPER (The Whitechapel Murders) VICTIMS 03 Apr 1888 - 13 Feb 1891 Compiled by Campbell M gold (2012) (This material has been compiled from various unconfirmed sources) CMG Archives http://campbellmgold.com --()-- Introduction The following material is a basic compilation of "facts" related to the Whitechapel murders. The sources include reported medical evidence, police comment, and inquest reports - as far as possible Ripper myths have not been considered. Additionally, where there was no other source available, newspaper reports have been used sparingly. No attempt has been made to identify the perpetrator of the murders and no conclusions have been made. Consequently, the reader is left to arrive at their own conclusions. Eleven Murders The Whitechapel Murders were a series of eleven murders which occurred between Apr 1888 and Feb 1891. Ten of the victims were prostitutes and one was an unidentified female (only the torso was found). It was during this period that the Jack the Ripper murders took place. Even today, 2012, it still remains unclear as to how many victims Jack the Ripper actually killed. However, it is generally accepted that he killed at least four of the "Canonical" five. Some researchers postulate that he murdered only four women, while others say that he killed as many as seven or more. Some earlier deaths have also been speculated upon as possible Ripper victims. 1 The murders were considered too much for the local Whitechapel (H) Division C.I.D, headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid, to handle alone. Assistance was sent from the Central Office at Scotland Yard, after the Nichols murder, in the persons of Detective Inspectors, Frederick George Abberline, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews, together with a team of subordinate officers. -

Splitter Kino

Splitter Kino Comic | F. Debois/J-C. Poupard: Jack the Ripper; X. Dorison/R. Meyer: Asgard Mit dem Label Splitter Double hat der umtriebige Comicverlag aus Bielefeld eine neue Reihe eröffnet, die zweibändige Comicerzählungen in jeweils einem großen Doppelband zusammenfasst, wodurch der Leser erstens etwas preisgünstiger wegkommt und zweitens ein kompakteres Lesevergnügen hat. Mit einem Splitter Double hält man in etwa das Äquivalent eines Kinoabends in den Händen – was sich auch in den ausgewählten Genres widerspiegelt. BORIS KUNZ hat zwei Tickets gelöst. Jack the Ripper Es gibt wohl kaum ein historisches Rätsel, um dessen Lösung die Popkultur so viele Spekulationen angestellt hat, wie die wahre Identität von Jack the Ripper, dem nie gefassten Vater aller Serienkiller. Inspektor Frederick Abberline, der damalige Leiter der Ermittlungen, ist selbst längst zu einer fiktionalen Figur geworden: In dem Kinofilm ›Wolfman‹ macht er Jagd auf Werwölfe, in der hervorragenden britischen Krimiserie ›Ripper Street‹ ist er noch immer besessen davon, Jack the Ripper endlich zu fassen. Auch die französischen Künstler Francois Debois und Jean-Charles Poupard machen Abberline zur zentralen Figur ihres neuen Ripper-Mythos und leiten ihre Story bereits auf den ersten Seiten im Erzähltext mit einer kühnen These ein: »Ich, Frederick Abberline, ich bin Jack the Ripper.« Zunächst einmal hält sich der Comic nah an die historischen Fakten, die Gottvater Alan Moore in seinem monumentalen ›From Hell‹ zum Allgemeinwissen eingefleischter Comicleser gemacht hat: Mehrere Prostituierte im Stadtviertel Whitechapel werden schrecklich verstümmelt aufgefunden, in London macht sich Angst breit. Der königliche Leibarzt Willliam Gull und sein Kutscher Netley treten recht bald in den Kreis der Verdächtigen – und auch in dieser Geschichte haben sie ihre Finger bei den Morden mit im Spiel. -

Jack L'eventreur Démasqué

SOPHIE HERFORT JACK L’ÉVENTREUR DÉMASQUÉ L’enquête définitive TEXTO Texto est une collection des éditions Tallandier Illustrations des cahiers iconographiques : © DR © Éditions Tallandier, 2007 et 2020 pour la présente édition 48, rue du Faubourg-Montmartre – 75009 Paris www.tallandier.com ISBN : 979-10-210-4442-5 SOMMAIRE Introduction ...................................................................... 9 Première partie LE CRIMINEL LE PLUS CÉLÈBRE DE TOUS LES TEMPS Chapitre premier – L’East End de l’Éventreur ........... 25 Chapitre II – Premier acte .............................................. 29 Chapitre III – À moitié décapitée… ............................. 39 Chapitre IV – Le tueur fut dérangé… ........................... 51 Chapitre V – La nuit du double meurtre ...................... 61 Chapitre VI – La plus horriblement mutilée ................ 73 Deuxième partie UN GENTLEMAN AU-DESSUS DE TOUT SOUPÇON Chapitre VII – L’exclusion qui a tout déclenché ......... 91 Chapitre VIII – Warren rejette Macnaghten ................ 97 Chapitre IX – La démission de Charles Warren.......... 111 Chapitre X – Le retour de Monro et de Macnaghten ... 123 Troisième partie L’ÉVENTREUR DÉMASQUÉ Chapitre XI – « Jack l’Empailleur » ................................ 141 Chapitre XII – La piste indienne .................................... 155 Chapitre XIII – « Attrapez-moi si vous pouvez ! » ...... 159 Chapitre XIV – Jack et le théâtre ................................... 163 Chapitre XV – Les « maladies » de Jack ........................ 171 Chapitre -

Mary Jane of Whitechapel

Mary Jane of Whitechapel A Play in One Act By Julian Felice Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Contact the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The author’s name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY hiStage.com © 2012 Julian Felice Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing https://histage.com/mary-jane-of-white-chapel Mary Jane of Whitechapel - 2 - DEDICATION To William and Natalie STORY OF THE PLAY Mary Jane of Whitechapel is set during the Autumn of Terror of 1888 when London was haunted by the spectre of a killer which, even now, we know only by the name of Jack the Ripper. Alternating between the investigation into the killings and the life of Mary Jane Kelly, the Ripper’s final victim, the play re-creates the dark atmosphere of a city horrified by blood and violence. The play is based on real people and incidents: the frantic officers on the case, the scores of suspects, the vigilantes who attack foreigners, and ordinary people, scared of going out at night. The chorus serves at different times as news vendors, passers-by, reporters, and even a line-up of six Rippers whose staccato lines are striking. The action flows seamlessly from pubs, to police station, to streets, and finally to a home where one man, peering in a window, discovers Mary Jane of Whitechapel took her last, terrorized breath. -

October, the Month When Nothing Happened

October/November 2017 No. 158 KARL COPPACK looks at October, the month when nothing happened JOE CHETCUTI MADELEINE KEANE NINA and HOW BROWN Exclusive on Francis The riotous career of The American Actor who Tumblety’s final days Chicago May sought to catch the Ripper while dressed in women’s JONATHAN MENGES JAN BONDESON clothes The death of the More from the first Mrs. Crippen Casebook of a Murder THE LATEST BOOK REVIEWS House Detective Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 158 October/November 2017 EDITORIAL: CASE CLOSED? Adam Wood A NUN’S LETTER Joe Chetcuti OCTOBER 1888: THE MONTH WHERE NOTHING HAPPENED Karl Coppack CONNECTIVE TISSUE: BELLE ELMORE, H.H. CRIPPEN AND THE DEATH OF CHARLOTTE BELL Jonathan Menges CHICAGO MAY DUIGNAN, THE QUEEN OF CROOKS Madeleine Keane A RICHMOND HORROR STORY and HUSBAND MURDER AT BATTERSEA Jan Bondeson DRAGNET! PT 2 Nina and Howard Brown VICTORIAN FICTION: LET LOOSE By Mary Cholmondeley Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.mangobooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. -

Mary Jane of Whitechapel

Mary Jane of Whitechapel A Play in One Act By Julian Felice Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Contact the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The author’s name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY hiStage.com © 2012 Julian Felice Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing http://www.histage.com/playdetails.asp?PID=2488 Mary Jane of Whitechapel - 2 - DEDICATION To William and Natalie STORY OF THE PLAY Mary Jane of Whitechapel is set during the Autumn of Terror of 1888 when London was haunted by the spectre of a killer which, even now, we know only by the name of Jack the Ripper. Alternating between the investigation into the killings and the life of Mary Jane Kelly, the Ripper’s final victim, the play re-creates the dark atmosphere of a city horrified by blood and violence. The play is based on real people and incidents: the frantic officers on the case, the scores of suspects, the vigilantes who attack foreigners, and ordinary people, scared of going out at night. The chorus serves at different times as news vendors, passers-by, reporters, and even a line-up of six Rippers whose staccato lines are striking. The action flows seamlessly from pubs, to police station, to streets, and finally to a home where one man, peering in a window, discovers Mary Jane of Whitechapel took her last, terrorized breath.