Treatment Patterns for Otitis Externa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

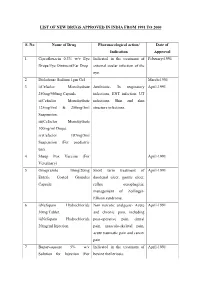

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

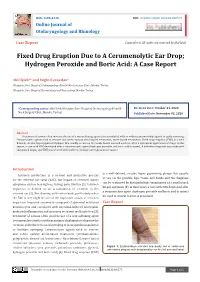

Fixed Drug Eruption Due to a Cerumenolytic Ear Drop; Hydrogen Peroxide and Boric Acid: a Case Report

ISSN: 2688-8238 DOI: 10.33552/OJOR.2020.04.000577 Online Journal of Otolaryngology and Rhinology Case Report Copyright © All rights are reserved by Akif İşlek Fixed Drug Eruption Due to A Cerumenolytic Ear Drop; Hydrogen Peroxide and Boric Acid: A Case Report Akif İşlek1* and Engin Karaaslan2 1Nusaybin State Hospital, Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery Clinic, Mardin, Turkey 2Nusaybin State Hospital, Dermatology and Venereology, Mardin, Turkey *Corresponding author: Received Date: October 24, 2020 Published Date: November 03, 2020 Akif İşlek, Nusaybin State Hospital, Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery Clinic, Mardin, Turkey. Abstract Treatment of earwax often involves the use of a wax softening agent (cerumenolytic) with or without antimicrobial agents to easily removing. Cerumenolytic agents used to remove and soften earwax areoil-based treatments, water-based treatments. Fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well- defined, circular, hyperpigmented plaque that usually occurs on the trunk, hands mucosal surfaces, after a systemical application of drugs. In this report, a case with FDE developed after a cerumenolytic agent (hydrogen peroxide and boric acid in water). A definitive diagnosis was made with skin punch biopsy and FDE was treated with oral levocetirizine and topical mometasone. Introduction is a well-defined, circular, hyper pigmenting plaque that usually Cerumen production is a normal and protective process occurs on the genitals, lips, trunk, and hands and the diagnosis for the external ear canal (EAC), but impact of cerumen causes can be confirmed by histopathologic examination of a small punch symptoms such as hearing loss, itching, pain, tinnitus [1]. Cerumen biopsy specimen [5]. In this report, a case with FDE developed after impaction is defined as an accumulation of cerumen in the a cerumenolytic agent (hydrogen peroxide and boric acid in water) external ear [2]. -

Antiseptics and Disinfectants for the Treatment Of

Verstraelen et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2012, 12:148 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/12/148 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Antiseptics and disinfectants for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review Hans Verstraelen1*, Rita Verhelst2, Kristien Roelens1 and Marleen Temmerman1,2 Abstract Background: The study objective was to assess the available data on efficacy and tolerability of antiseptics and disinfectants in treating bacterial vaginosis (BV). Methods: A systematic search was conducted by consulting PubMed (1966-2010), CINAHL (1982-2010), IPA (1970- 2010), and the Cochrane CENTRAL databases. Clinical trials were searched for by the generic names of all antiseptics and disinfectants listed in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System under the code D08A. Clinical trials were considered eligible if the efficacy of antiseptics and disinfectants in the treatment of BV was assessed in comparison to placebo or standard antibiotic treatment with metronidazole or clindamycin and if diagnosis of BV relied on standard criteria such as Amsel’s and Nugent’s criteria. Results: A total of 262 articles were found, of which 15 reports on clinical trials were assessed. Of these, four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were withheld from analysis. Reasons for exclusion were primarily the lack of standard criteria to diagnose BV or to assess cure, and control treatment not involving placebo or standard antibiotic treatment. Risk of bias for the included studies was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. Three studies showed non-inferiority of chlorhexidine and polyhexamethylene biguanide compared to metronidazole or clindamycin. One RCT found that a single vaginal douche with hydrogen peroxide was slightly, though significantly less effective than a single oral dose of metronidazole. -

Folic Acid Antagonists: Antimicrobial and Immunomodulating Mechanisms and Applications

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Folic Acid Antagonists: Antimicrobial and Immunomodulating Mechanisms and Applications Daniel Fernández-Villa 1, Maria Rosa Aguilar 1,2 and Luis Rojo 1,2,* 1 Instituto de Ciencia y Tecnología de Polímeros, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC, 28006 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (D.F.-V.); [email protected] (M.R.A.) 2 Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Bioingeniería, Biomateriales y Nanomedicina, 28029 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-915-622-900 Received: 18 September 2019; Accepted: 7 October 2019; Published: 9 October 2019 Abstract: Bacterial, protozoan and other microbial infections share an accelerated metabolic rate. In order to ensure a proper functioning of cell replication and proteins and nucleic acids synthesis processes, folate metabolism rate is also increased in these cases. For this reason, folic acid antagonists have been used since their discovery to treat different kinds of microbial infections, taking advantage of this metabolic difference when compared with human cells. However, resistances to these compounds have emerged since then and only combined therapies are currently used in clinic. In addition, some of these compounds have been found to have an immunomodulatory behavior that allows clinicians using them as anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive drugs. Therefore, the aim of this review is to provide an updated state-of-the-art on the use of antifolates as antibacterial and immunomodulating agents in the clinical setting, as well as to present their action mechanisms and currently investigated biomedical applications. Keywords: folic acid antagonists; antifolates; antibiotics; antibacterials; immunomodulation; sulfonamides; antimalarial 1. -

Identification of Candidate Agents Active Against N. Ceranae Infection in Honey Bees: Establishment of a Medium Throughput Screening Assay Based on N

RESEARCH ARTICLE Identification of Candidate Agents Active against N. ceranae Infection in Honey Bees: Establishment of a Medium Throughput Screening Assay Based on N. ceranae Infected Cultured Cells Sebastian Gisder, Elke Genersch* Institute for Bee Research, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Bee Diseases, Hohen Neuendorf, Germany * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Many flowering plants in both natural ecosytems and agriculture are dependent on insect Citation: Gisder S, Genersch E (2015) Identification of Candidate Agents Active against N. ceranae pollination for fruit set and seed production. Managed honey bees (Apis mellifera) and wild Infection in Honey Bees: Establishment of a Medium bees are key pollinators providing this indispensable eco- and agrosystem service. Like all Throughput Screening Assay Based on N. ceranae other organisms, bees are attacked by numerous pathogens and parasites. Nosema apis is Infected Cultured Cells. PLoS ONE 10(2): e0117200. a honey bee pathogenic microsporidium which is widely distributed in honey bee popula- doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117200 tions without causing much harm. Its congener Nosema ceranae was originally described Academic Editor: Wolfgang Blenau, Goethe as pathogen of the Eastern honey bee (Apis cerana) but jumped host from A. cerana to A. University Frankfurt, GERMANY mellifera about 20 years ago and spilled over from A. mellifera to Bombus spp. quite recent- Received: October 8, 2014 ly. N. ceranae is now considered a deadly emerging parasite of both Western honey bees Accepted: December 20, 2014 and bumblebees. Hence, novel and sustainable treatment strategies against N. ceranae are Published: February 6, 2015 urgently needed to protect honey and wild bees. -

4. Antibacterial/Steroid Combination Therapy in Infected Eczema

Acta Derm Venereol 2008; Suppl 216: 28–34 4. Antibacterial/steroid combination therapy in infected eczema Anthony C. CHU Infection with Staphylococcus aureus is common in all present, the use of anti-staphylococcal agents with top- forms of eczema. Production of superantigens by S. aureus ical corticosteroids has been shown to produce greater increases skin inflammation in eczema; antibacterial clinical improvement than topical corticosteroids alone treatment is thus pivotal. Poor patient compliance is a (6, 7). These findings are in keeping with the demon- major cause of treatment failure; combination prepara- stration that S. aureus can be isolated from more than tions that contain an antibacterial and a topical steroid 90% of atopic eczema skin lesions (8); in one study, it and that work quickly can improve compliance and thus was isolated from 100% of lesional skin and 79% of treatment outcome. Fusidic acid has advantages over normal skin in patients with atopic eczema (9). other available topical antibacterial agents – neomycin, We observed similar rates of infection in a prospective gentamicin, clioquinol, chlortetracycline, and the anti- audit at the Hammersmith Hospital, in which all new fungal agent miconazole. The clinical efficacy, antibac- patients referred with atopic eczema were evaluated. In terial activity and cosmetic acceptability of fusidic acid/ a 2-month period, 30 patients were referred (22 children corticosteroid combinations are similar to or better than and 8 adults). The reason given by the primary health those of comparator combinations. Fusidic acid/steroid physician for referral in 29 was failure to respond to combinations work quickly with observable improvement prescribed treatment, and one patient was referred be- within the first week. -

Clioquinol: Summary Report

Clioquinol: Summary Report Item Type Report Authors Gianturco, Stephanie L.; Pavlech, Laura L.; Storm, Kathena D.; Yoon, SeJeong; Yuen, Melissa V.; Mattingly, Ashlee N. Publication Date 2020-01 Keywords Clioquinol; Compounding; Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, Section 503B; Food and Drug Administration; Outsourcing facility; Drug compounding; Legislation, Drug; United States Food and Drug Administration Rights Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 24/09/2021 22:12:31 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10713/12091 Summary Report Clioquinol Prepared for: Food and Drug Administration Clinical use of bulk drug substances nominated for inclusion on the 503B Bulks List Grant number: 2U01FD005946 Prepared by: University of Maryland Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (M-CERSI) University of Maryland School of Pharmacy January 2020 This report was supported by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award (U01FD005946) totaling $2,342,364, with 100 percent funded by the FDA/HHS. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, the FDA/HHS or the U.S. Government. 1 Table of Contents REVIEW OF NOMINATIONS ................................................................................................... 4 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................... -

Effect of 8-Hydroxyquinoline and Derivatives on Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells Under High Glucose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Effect of 8-hydroxyquinoline and derivatives on human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells under high glucose Wilasinee Suwanjang1, Supaluk Prachayasittikul2 and Virapong Prachayasittikul3 1 Center for Research and Innovation, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand 2 Center of Data Mining and Biomedical Informatics, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand 3 Department of Clinical Microbiology and Applied Technology, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand ABSTRACT 8-Hydroxyquinoline and derivatives exhibit multifunctional properties, including antioxidant, antineurodegenerative, anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic activities. In biological systems, elevation of intracellular calcium can cause calpain activation, leading to cell death. Here, the effect of 8-hydroxyquinoline and derivatives (5-chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline or clioquinol and 8-hydroxy-5-nitroquinoline or nitroxoline) on calpain-dependent (calpain-calpastatin) pathways in human neu- roblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells was investigated. 8-Hydroxyquinoline and derivatives ameliorated high glucose toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. The investigated compounds, particularly clioquinol, attenuated the increased expression of calpain, even under high- glucose conditions. 8-Hydroxyquinoline and derivatives thus adversely affected the promotion of neuronal cell death by high glucose via the calpain-calpastatin -

Common Ear, Nose & Throat Problems

Common Ear, Nose & Throat Problems The information provided in this presentation is not intended to guide treatment or aid in making a diagnosis. Always consult a physician or nurse practitioner. Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Normal Larynx Normal larynx in a 44 yr old non-smoker Go to http://www.entusa.com/normal_larynx.htm to View Video Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Acute Laryngitis This video shows the function of the larynx in a 24 yr old patient with acute laryngitis. Talking was painful and she only talked in a faint whisper. Go to http://www.entusa.com/laryngitis.htm to View Video Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Vocal Cord Paralysis This video shows the function of a larynx with a paralyzed left true vocal cord. The patient has lung cancer. She has a poorly compensated breathy voice which is difficult to understand. This patient had a 55 pack year history of smoking. Go to http://www.entusa.com/vocal_cord_paralysis_2.htm to View Video Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Vocal Cord Polyp This video shows the function of a larynx with a vocal cord polyp on the right true vocal cord. This patient smoked one pack a day for 30 years. Go to http://www.entusa.com/larynx_polyp-9.htm to View Video Copyright 2002, 2014, Kevin T. Kavanagh All Rights Reserved www.entusa.com Laryngeal Cancer This video shows the function of a larynx with a large T1b Cancer on both true vocal cords and anterior commissure in 72 yr old male with a 150 pack year history of smoking. -

Transdermal Drug Delivery Device Including An

(19) TZZ_ZZ¥¥_T (11) EP 1 807 033 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61F 13/02 (2006.01) A61L 15/16 (2006.01) 20.07.2016 Bulletin 2016/29 (86) International application number: (21) Application number: 05815555.7 PCT/US2005/035806 (22) Date of filing: 07.10.2005 (87) International publication number: WO 2006/044206 (27.04.2006 Gazette 2006/17) (54) TRANSDERMAL DRUG DELIVERY DEVICE INCLUDING AN OCCLUSIVE BACKING VORRICHTUNG ZUR TRANSDERMALEN VERABREICHUNG VON ARZNEIMITTELN EINSCHLIESSLICH EINER VERSTOPFUNGSSICHERUNG DISPOSITIF D’ADMINISTRATION TRANSDERMIQUE DE MEDICAMENTS AVEC COUCHE SUPPORT OCCLUSIVE (84) Designated Contracting States: • MANTELLE, Juan AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR Miami, FL 33186 (US) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI • NGUYEN, Viet SK TR Miami, FL 33176 (US) (30) Priority: 08.10.2004 US 616861 P (74) Representative: Awapatent AB P.O. Box 5117 (43) Date of publication of application: 200 71 Malmö (SE) 18.07.2007 Bulletin 2007/29 (56) References cited: (73) Proprietor: NOVEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. WO-A-02/36103 WO-A-97/23205 Miami, FL 33186 (US) WO-A-2005/046600 WO-A-2006/028863 US-A- 4 994 278 US-A- 4 994 278 (72) Inventors: US-A- 5 246 705 US-A- 5 474 783 • KANIOS, David US-A- 5 474 783 US-A1- 2001 051 180 Miami, FL 33196 (US) US-A1- 2002 128 345 US-A1- 2006 034 905 Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

EAR, NOSE and OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020

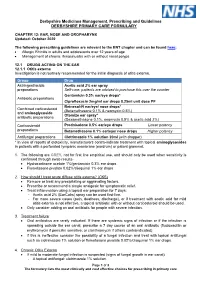

Derbyshire Medicines Management, Prescribing and Guidelines DERBYSHIRE PRIMARY CARE FORMULARY CHAPTER 12: EAR, NOSE AND OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020 The following prescribing guidelines are relevant to the ENT chapter and can be found here: • Allergic Rhinitis in adults and adolescents over 12 years of age • Management of chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps 12.1 DRUGS ACTING ON THE EAR 12.1.1 Otitis externa Investigation is not routinely recommended for the initial diagnosis of otitis externa. Group Drug Astringent/acidic Acetic acid 2% ear spray preparations Self-care: patients are advised to purchase this over the counter Gentamicin 0.3% ear/eye drops* Antibiotic preparations Ciprofloxacin 2mg/ml ear drops 0.25ml unit dose PF Betnesol-N ear/eye/ nose drops* Combined corticosteroid (Betamethasone 0.1% & neomycin 0.5%) and aminoglycoside Otomize ear spray* antibiotic preparations (Dexamethasone 0.1%, neomycin 0.5% & acetic acid 2%) Corticosteroid Prednisolone 0.5% ear/eye drops Lower potency preparations Betamethasone 0.1% ear/eye/ nose drops Higher potency Antifungal preparations Clotrimazole 1% solution 20ml (with dropper) * In view of reports of ototoxicity, manufacturers contra-indicate treatment with topical aminoglycosides in patients with a perforated tympanic membrane (eardrum) or patent grommet. 1. The following are GREY, not for first line empirical use, and should only be used when sensitivity is confirmed through swab results- • Hydrocortisone acetate 1%/gentamicin 0.3% ear drops • Flumetasone pivalate 0.02%/clioquinol 1% ear drops 2. How should I treat acute diffuse otitis externa? (CKS) • Remove or treat any precipitating or aggravating factors. • Prescribe or recommend a simple analgesic for symptomatic relief. -

10/15-Hour Medication Test Answers

Appendix 10/15-Hour Medication Test Answers Name _________________________________ Facility _________________________________ Part 1: Match the term or phrase on the right with the abbreviation or term on the left by placing the correct letter on the appropriate line. _____ 1. PRN (p) a. milligram _____ 2. ac (e) b. at bedtime _____ 3. stat (j) c. Medication Administration Record _____ 4. SL (k) d. over the counter _____ 5. MAR (c) e. before meals _____ 6. mg (a) f. tablespoonful _____ 7. pc (m) g. placed and affixed to the skin _____ 8. OTC (d) h. teaspoonful _____ 9. Subcutaneous (r) i. milliliter _____ 10. po (n) j. immediately _____ 11. qhs (b) k. sublingual _____ 12. tbsp (f) l. placed under the tongue _____ 13. transdermal (g) m. after meals _____ 14. ml (i) n. by mouth _____ 15. gm (o) o. gram _____ 16. QOD (q) p. as needed _____ 17. tsp (h) q. every other day _____ 18. sublingual (l) r. inject into the fat with a syringe Medication Administration – March 2021 10/15-Hour Training Course for Adult Care Homes 4 Appendix 10/15-Hour Medication Test Answers – Continued Part 2: Fill in the blank with the appropriate word or term. You may choose to use the word bank below. 19. A heart tablet taken by mouth and swallowed is an example of a medication taken by the oral route. 20. A medication that is inserted into the rectum is given using the rectal route. 21. A topical medication is applied directly to the skin surface.