Video Game Music, Gamers, and Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Gaming Music: Composition

KSKS45 Computer gaming music: composition James Manwaring by James Manwaring is Director of Music for Windsor Learning Partnership, and has been teaching music for 15 years. He is a member of INTRODUCTION the MMA and ISM, and he writes his One of the key emerging genres of music over the last 35 years has been computer game music. Since the own music blog. first playable version of Tetris in 1984, music in this genre has grown. We now see key orchestral and cinema composers turning their hands to computer game soundtracks. If we’re going to prepare our students for future work in the music industry, it’s crucial for them to embrace all styles and genres. Following an earlier resource on gaming music (AQA AoS2: Computer gaming music, Music Teacher, November 2018), here I’m going to consider ways of teaching computer game music using composition. This will include some compositional ideas that can easily be adapted for other genres. STARTING POINT Composition is a key component for all the GCSE exam boards, and while each exam board has different criteria, they all share similar, overarching compositional goals. The ideas in this resource can either lead to something suitable for a GCSE entry, or help with the overall teaching of composition. The aim is to use computer games as the key focus for the composing process. Students will probably spend a great deal of time playing computer games. Not only will they have an excellent grasp of music from this genre, but they will also be keen to have a go at composing it for themselves. -

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

Download the Catalog

WE SERVE BUSINESSES OF ALL SIZES WHO WE ARE We are an ambitious laser tag design and manufacturing company with a passion for changing the way people EXPERIENCE LIVE-COMBAT GAMING. We PROVIDE MANUFACTURING and support to businesses both big or small, around the world! With fresh thinking and INNOVATIVE GAMING concepts, our reputation has made us a leader in the live-action gaming space. One of the hallmarks of our approach to DESIGN & manufacturing is equipment versatility. Whether operating an indoor arena, outdoor battleground, mobile business, or a special entertainment OUR PRODUCTS HAVE THE HIGHEST REPLAY attraction our equipment can be CUSTOMIZED TO FIT your needs. Battle Company systems will expand your income opportunities and offer possibilities where the rest of the industry can only provide VALUE IN THE LASER TAG INDUSTRY limitations. Our products are DESIGNED AND TESTED at our 13-acre property headquarters. We’ve put the equipment into action in our 5,000 square-foot indoor laser tag facility as well as our newly constructed outdoor battlefield. This is to ensure the highest level of design quality across the different types of environments where laser tag is played. Using Agile development methodology and manufacturing that is ISO 9001 CERTIFIED, we are the fastest manufacturer in the industry when it comes to bringing new products and software to market. Battle Company equipment has a strong competitive advantage over other brands and our COMMITMENT TO R&D is the reason why we are leading the evolution of the laser tag industry! 3 OUT OF 4 PLAYERS WHO USE BATTLE COMPANY BUSINESSES THAT CHOOSE US TO POWER THEIR EXPERIENCE EQUIPMENT RETURN TO PLAY AGAIN! WE SERVE THE MILITARY 3 BIG ATTRACTION SMALL FOOTPRINT Have a 10ft x 12.5ft space not making your facility much money? Remove the clutter and fill that area with the Battle Cage. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Deepcrawl: Deep Reinforcement Learning for Turn-Based Strategy Games

DeepCrawl: Deep Reinforcement Learning for Turn-based Strategy Games Alessandro Sestini,1 Alexander Kuhnle,2 Andrew D. Bagdanov1 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Informazione, Universita` degli Studi di Firenze, Florence, Italy 2Department of Computer Science and Technology, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom falessandro.sestini, andrew.bagdanovg@unifi.it Abstract super-human skills able to solve a variety of environments. However the main objective of DRL of this type is training In this paper we introduce DeepCrawl, a fully-playable Rogue- like prototype for iOS and Android in which all agents are con- agents to surpass human players in competitive play in clas- trolled by policy networks trained using Deep Reinforcement sical games like Go (Silver et al. 2016) and video games Learning (DRL). Our aim is to understand whether recent ad- like DOTA 2 (OpenAI 2019). The resulting, however, agents vances in DRL can be used to develop convincing behavioral clearly run the risk of being too strong, of exhibiting artificial models for non-player characters in videogames. We begin behavior, and in the end not being a fun gameplay element. with an analysis of requirements that such an AI system should Video games have become an integral part of our entertain- satisfy in order to be practically applicable in video game de- ment experience, and our goal in this work is to demonstrate velopment, and identify the elements of the DRL model used that DRL techniques can be used as an effective game design in the DeepCrawl prototype. The successes and limitations tool for learning compelling and convincing NPC behaviors of DeepCrawl are documented through a series of playability tests performed on the final game. -

Application of Retrograde Analysis to Fighting Games

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2019 Application of Retrograde Analysis to Fighting Games Kristen Yu University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Commons, and the Game Design Commons Recommended Citation Yu, Kristen, "Application of Retrograde Analysis to Fighting Games" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1633. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1633 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Application of Retrograde Analysis to Fighting Games A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Daniel Felix Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Kristen Yu June 2019 Advisor: Nathan Sturtevant ©Copyright by Kristen Yu 2019 All Rights Reserved Author: Kristen Yu Title: Application of Retrograde Analysis to Fighting Games Advisor: Nathan Sturtevant Degree Date: June 2019 Abstract With the advent of the fighting game AI competition [34], there has been re- cent interest in two-player fighting games. Monte-Carlo Tree-Search approaches currently dominate the competition, but it is unclear if this is the best approach for all fighting games. In this thesis we study the design of two-player fighting games and the consequences of the game design on the types of AI that should be used for playing the game, as well as formally define the state space that fighting games are based on. -

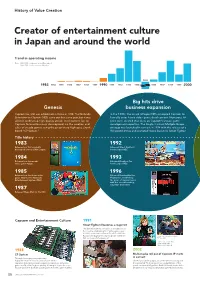

History of Value Creation

History of Value Creation Creator of entertainment culture in Japan and around the world Trend in operating income Note: 1983–1988: Fiscal years ended December 31 1989–2020: Fiscal years ended March 31 1995 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Big hits drive Genesis business expansion Capcom Co., Ltd. was established in Osaka in 1983. The Nintendo In the 1990s, the arrival of Super NES prompted Capcom to Entertainment System (NES) came out that same year, but it was formally enter home video game development. Numerous hit difficult to develop high-quality arcade-level content for, so titles were created that drew on Capcom’s arcade game Capcom focused business development on the creation and development expertise. The Single Content Multiple Usage sales of arcade games using the proprietary high-spec circuit strategy was launched in earnest in 1994 with the release of a board “CP System.” Hollywood movie and animated movie based on Street Fighter. Title history 1983 1992 Released our first originally Released Street Fighter II developed coin-op Little League. for the Super NES. 1984 1993 Released our first arcade Released Breath of Fire video game Vulgus. for the Super NES. 1985 1996 Released our first home video Released Resident Evil for game 1942 for the Nintendo PlayStation, establishing Entertainment System (NES). the genre of survival horror with this record-breaking, long-time best-seller. 1987 Released Mega Man for the NES. Capcom and Entertainment Culture 1991 Street Fighter II becomes a major hit The game became a sensation in arcades across the country, establishing the fighting game genre. -

Design Guidelines for Audio Games

Design Guidelines for Audio Games Franco Eusébio Garcia and Vânia Paula de Almeida Neris Federal University of Sao Carlos (UFSCar), Sao Carlos, Brazil {franco.garcia,vania}@dc.ufscar.br Abstract. This paper presents guidelines to aid on the design of audio games. Audio games are games on which the user interface and game events use pri- marily sounds instead of graphics to convey information to the player. Those games can provide an accessible gaming experience to visually impaired play- ers, usually handicapped by conventional games. The presented guidelines resulted of existing literature research on audio games design and implementa- tion, of a case study and of a user observation performed by the authors. The case study analyzed how audio is used to create an accessible game on nine au- dio games recommended for new players. The user observation consisted of a playtest on which visually impaired users played an audio game, on which some interaction problems were identified. The results of those three studies were analyzed and compiled in 50 design guidelines. Keywords: audio games, accessibility, visual impairment, design, guidelines. 1 Introduction The evolution of digital interfaces continually provides simpler, easier and more intui- tive ways of interaction. Especially in games, the way a player interacts with the system may affect his/her overall playing experience, immersion and satisfaction. Currently, game interfaces mostly rely on graphics to convey information to the play- er. Albeit being an effective way to convey information to the average user, graphical interfaces might be partially or even totally inaccessible to the visually impaired. Those users are either unable or have a hard time playing a conventional game, as the graphical content of the user interface is usually essential to the gameplay. -

Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music

Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music Elizabeth Medina-Gray KEYWORDS: video game music, modular music, smoothness, probability, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, Portal 2 ABSTRACT: This article provides a detailed method for analyzing smoothness in the seams between musical modules in video games. Video game music is comprised of distinct modules that are triggered during gameplay to yield the real-time soundtracks that accompany players’ diverse experiences with a given game. Smoothness —a quality in which two convergent musical modules fit well together—as well as the opposite quality, disjunction, are integral products of modularity, and each quality can significantly contribute to a game. This article first highlights some modular music structures that are common in video games, and outlines the importance of smoothness and disjunction in video game music. Drawing from sources in the music theory, music perception, and video game music literature (including both scholarship and practical composition guides), this article then introduces a method for analyzing smoothness at modular seams through a particular focus on the musical aspects of meter, timbre, pitch, volume, and abruptness. The method allows for a comprehensive examination of smoothness in both sequential and simultaneous situations, and it includes a probabilistic approach so that an analyst can treat all of the many possible seams that might arise from a single modular system. Select analytical examples from The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker and Portal -

Playing with Sound and Gesture in Digital Audio Games

“proceedings” — 2015/7/27 — 18:40 — page 423 — #435 A. Weisbecker, M. Burmester & A. Schmidt (Hrsg.): Mensch und Computer 2015 Workshopband, Stuttgart: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2015, S. 423-429. Playing with sound and gesture in digital audio games Dr. Sonia Fizek 1, Dr. Julie Woletz 2, Jarosław Beksa 3 Gamification Lab, Centre for Digital Cultures, Leuphana University Lüneburg 1 Media Uselab, Centre for Digital Cultures, Leuphana University Lüneburg 2 School of Computer and Mathematical Sciences, Auckland University of Technology 3 Abstract This article introduces the genre of a digital audio game and discusses selected play interaction solu- tions implemented in the Audio Game Hub , a prototype designed and evaluated in the years 2014 and 2015 at the Gamification Lab at Leuphana University Lüneburg. 1 The Audio Game Hub constitutes a set of familiar playful activities (aiming at a target, reflex-based reacting to sound signals, labyrinth exploration) and casual games (e.g. Tetris , Memory ) adapted to the digital medium and converted into the audio sphere, where the player is guided predominantly or solely by sound. The authors will discuss the design questions raised at early stages of the project, and confront them with the results of user experience testing performed on two groups of sighted and one group of visually impaired gamers. 1 Introducing digital audio games Have you been mesmerized in your childhood by playing the “ blind man's buff“? Or maybe you always wondered why the fables read out by your parents were far more magical than their counterparts watched on the TV screen? After all, sounds have limitless potential to create beautifully immersive sceneries without the help of a single paintbrush or animated pixel.