Using Superheroes to Teach Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legion HANDBOOK D10944

THE OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF THE LEGION OF MARY PUBLISHED BY CONCILIUM LEGIONIS MARIAE DE MONTFORT HOUSE MORNING STAR AVENUE BRUNSWICK STREET DUBLIN 7, IRELAND Revised Edition, 2005 Nihil Obstat: Bede McGregor, O.P., M.A., D.D. Censor Theologicus Deputatus. Imprimi potest: ✠ Diarmuid Martin Archiep. Dublinen. Hiberniae Primas. Dublin, die 8 September 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 1973, International Committee on English in the Liturgy, Inc. All rights reserved. Translation of The Magnificat by kind permission of A. P. Watt Ltd. on behalf of The Grail. Extracts from English translations of documents of the Magisterium by kind permission of the Catholic Truth Society (London) and Veritas (Dublin). Quotation on page 305 by kind permission of Sheed and Ward. The official magazine of the Legion of Mary, Maria Legionis, is published quarterly Presentata House, 263 North Circular Road, Dublin 7, Ireland. © Copyright 2005 Printed in the Republic of Ireland by Mahons, Yarnhall Street, Dublin 1 Contents Page ABBREVIATIONS OF BOOKS OF THE BIBLE ....... 3 ABBREVIATIONS OF DOCUMENTS OF THE MAGISTERIUM .... 4 POPE JOHN PAUL II TO THE LEGION OF MARY ...... 5 PRELIMINARY NOTE.............. 7 PROFILE OF FRANK DUFF .......... 8 PHOTOGRAPHS:FRANK DUFF .......facing page 8 LEGION ALTAR ......facing page 108 VEXILLA ........facing page 140 CHAPTER 1. Name and Origin ............ 9 2. Object . ...............11 3. Spirit of the Legion . ...........12 4. Legionary service ............13 5. The Devotional Outlook of the Legion .....17 6. The Duty of Legionaries towards Mary .....25 7. The Legionary and the Holy Trinity ......41 8. The Legionary and the Eucharist .......45 9. -

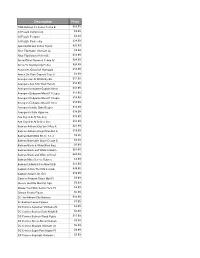

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

Captain America

The Star-spangled Avenger Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Captain America first appeared in Captain America Comics #1 (Cover dated March 1941), from Marvel Comics' 1940s predecessor, Timely Comics, and was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. For nearly all of the character's publication history, Captain America was the alter ego of Steve Rogers , a frail young man who was enhanced to the peak of human perfection by an experimental serum in order to aid the United States war effort. Captain America wears a costume that bears an American flag motif, and is armed with an indestructible shield that can be thrown as a weapon. An intentionally patriotic creation who was often depicted fighting the Axis powers. Captain America was Timely Comics' most popular character during the wartime period. After the war ended, the character's popularity waned and he disappeared by the 1950s aside from an ill-fated revival in 1953. Captain America was reintroduced during the Silver Age of comics when he was revived from suspended animation by the superhero team the Avengers in The Avengers #4 (March 1964). Since then, Captain America has often led the team, as well as starring in his own series. Captain America was the first Marvel Comics character adapted into another medium with the release of the 1944 movie serial Captain America . Since then, the character has been featured in several other films and television series, including Chris Evans in 2011’s Captain America and The Avengers in 2012. The creation of Captain America In 1940, writer Joe Simon conceived the idea for Captain America and made a sketch of the character in costume. -

Historic District Design Standards Were Produced with Participation and Input from the Following Individuals and Committees

Center Street Historic District Design Standards ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Logan Center Street Historic District Design Standards were produced with participation and input from the following individuals and committees: Steering Committee: Municipal Council: o George Daines o Holly Daines o Kristan Fjeldsted o Tom Jensen* o Jeff Gilbert o S. Eugene Needham o Heather Hall o Herm Olsen o Jonathan Jenkins o Jeannie Simmonds* o Gene Needham IV *Indicates participation on the Steering Committee o Chris Sands o Gary Saxton Logan City: o Evan Stoker o Mayor Craig Petersen o Katie Stoker o Michael DeSimone, Community Development o Russ Holley, Community Development Historic Preservation Commission (HPC): o Amber Pollan, Community Development o Viola Goodwin o Aaron Smith, Community Development o Tom Graham* o Debbie Zilles, Community Development o Amy Hochberg o Kirk Jensen, Economic Development o David Lewis* o Keith Mott IO Design Collaborative o Gary Olsen o Kristen Clifford o Christian Wilson o Shalae Larsen o Mark Morris Planning Commission: o Laura Bandara o David Butterfield o Susan Crook o Amanda Davis Adopted __________ o Dave Newman* o Tony Nielson o Eduardo Ortiz o Russ Price* o Sara Sinclair TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Chapter 1 Introduction 6 Chapter 2 Historic Overview of Logan 6 Chapter 3 The Value of Historic Preservation 8 3.1 Historic Significance 9 3.2 Benefits of Historic Preservation 9 3.3 Sustainability 10 Chapter 4 Four Treatments of Historic Properties 11 Chapter 5 Preservation Incentives 12 Chapter 6 The Design Standards 14 6.1 Purpose 14 6.2 How to Use 14 Chapter 7 The Historic Preservation Committee & Project Review 15 7.1 The Committee 15 7.2 Project Review 15 Design Standards Chapter 8 Residential 19 8.1 Residential Historic Overview 19 8.2 Building Materials & Finishes 20 8.3 Windows 23 8.4 Doors 25 8.5 Porches & Architectural Details 26 8.6 Roofs 27 8.7 Additions 28 8.8 Accessory Structures 30 8.9 General 31 8.10 Design for New Construction & Infill 36 TABLE OF CONTENTS cont. -

The Avengers (Action) (2012)

1 The Avengers (Action) (2012) Major Characters Captain America/Steve Rogers...............................................................................................Chris Evans Steve Rogers, a shield-wielding soldier from World War II who gained his powers from a military experiment. He has been frozen in Arctic ice since the 1940s, after he stopped a Nazi off-shoot organization named HYDRA from destroying the Allies with a mystical artifact called the Cosmic Cube. Iron Man/Tony Stark.....................................................................................................Robert Downey Jr. Tony Stark, an extravagant billionaire genius who now uses his arms dealing for justice. He created a techno suit while kidnapped by terrorist, which he has further developed and evolved. Thor....................................................................................................................................Chris Hemsworth He is the Nordic god of thunder. His home, Asgard, is found in a parallel universe where only those deemed worthy may pass. He uses his magical hammer, Mjolnir, as his main weapon. The Hulk/Dr. Bruce Banner..................................................................................................Mark Ruffalo A renowned scientist, Dr. Banner became The Hulk when he became exposed to gamma radiation. This causes him to turn into an emerald strongman when he loses his temper. Hawkeye/Clint Barton.........................................................................................................Jeremy -

Marvel Universe 3.75" Action Figure Checklist

Marvel Universe 3.75" Action Figure Checklist Series 1 - Fury Files Wave 1 • 001 - Iron Man (Modern Armor) • 002 - Spider-Man (red/blue costume) (Light Paint Variant) • 002 - Spider-Man (red/blue costume) (Dark Paint Variant) • 003 - Silver Surfer • 004 - Punisher • 005 - Black Panther • 006 - Wolverine (X-Force costume) • 007 - Human Torch (Flamed On) • 008 - Daredevil (Light Red Variant) • 008 - Daredevil (Dark Red Variant) • 009 - Iron Man (Stealth Ops) • 010 - Bullseye (Light Paint Variant) • 010 - Bullseye (Dark Paint Variant) • 011 - Human Torch (Light Blue Costume) • 011 - Human Torch (Dark Blue Costume) Wave 2 • 012 - Captain America (Ultimates) • 013 - Hulk (Green) • 014 - Hulk (Grey) • 015 - Green Goblin • 016 - Ronin • 017 - Iron Fist (Yellow Dragon) • 017 - Iron Fist (Black Dragon Variant) Wave 3 • 018 - Black Costume Spider-Man • 019 - The Thing (Light Pants) • 019 - The Thing (Dark Pants) • 020 - Punisher (Modern Costume & New Head Sculpt) • 021 - Iron Man (Classic Armor) • 022 - Ms. Marvel (Modern Costume) • 023 - Ms. Marvel (Classic Red, Carol Danvers) • 023 - Ms. Marvel (Classic Red, Karla Sofen) • 024 - Hand Ninja (Red) Wave 4 • 026 - Union Jack • 027 - Moon Knight • 028 - Red Hulk • 029 - Blade • 030 - Hobgoblin Wave 5 • 025 - Electro • 031 - Guardian • 032 - Spider-man (Red and Blue, right side up) • 032 - Spider-man (Black and Red, upside down Variant) • 033 - Iron man (Red/Silver Centurion) • 034 - Sub-Mariner (Modern) Series 2 - HAMMER Files Wave 6 • 001 - Spider-Man (House of M) • 002 - Wolverine (Xavier School) -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

M AA Teamups.Wps

Marvel : Avengers Alliance team-ups by Team-Up name _ Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. (50 points) = Black Widow / Hawkeye / Mockingbird Ambulancechasers (50 points) = Dare Devil / She Hulk Arachnophobia (50 points) = Spiderman / Black Widow / Spiderwoman Asgard (50 points) = Thor / Sif Assemble (50 points) = Thor / Hulk / Hawkeye / Black Widow / Ironman / Captain America Aviary (50 points) = all Heroes with a Flying ability Best Coast (50 points) = Hawkeye / Mockingbird / War Machine Birds of a Feather (50 points)= Hawkeye / Mockingbird Bloodlust (50 points) = Wolverine / Black Cat / Sif Cat Fight (50 points) = Kitty Pryde / Black Cat Cosplayers (50 points) = Spiderman / Black Cat Defenders (50 points) = Dr.Strange / Hulk Egghead (50 points) = Hulk / Spiderman / Ironman / Mr.Fantastic Fantastic 4 (50 points) = all Fantastic 4 members Frenemies, Assemble (50 points) = Hawkeye / Black Widow Green Giants (50 points) = She-Hulk / Hulk Heroesforhire (50 points) = Luke Cage / Iron Fist Hard and Soft (50 points) = Kitty Pryde / Colossus Hotstuff (50 points) = Phoenix / Human Torch Illuminati (50 points) = Dr.Strange / Mr.Fantastic / Ironman King&Queen (50 points) = Black Panther / Storm Marvelous (50 points) = Phoenix / Ms. Marvel Sibling Rivalry (50 points) = Invisible Woman / Human Torch Tinmen (50 points) = War Machine / Iron Man Tossers (50 points) = Thing / Hulk / She-Hulk / Phoenix X-Force (50 points) = all X-Men members X-lovers (50 points) = Cyclops / Phoenix by Hero name _ Black Cat + Wolverine / Black Cat / Sif = Bloodlust (50 points) Black Cat + Kitty Pryde = Cat Fight (50 points) Black Cat + Spiderman = Cosplayers (50 points) Black Panther + Storm = King&Queen (50 points) Black Widow + Hawkeye / Mockingbird = Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership.