Crocodile Lake NWR CCP.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venomous and Poisonous Critters

Quick Dangerous Florida Arachnid Guide Widow Spiders - 4 species in Florida - Latrodectus spp Brown, red, N black and S black widows Bite: No mark. Pain like a needle stick. Muscle twitching/spasms, cramps, vomiting, sweating, headache, severe trunk pain. Cleanse with soap & water.Cool compresses. Emergency department for observation and treatment. " " A young red widow An adult black widow Recluse Spiders - 3 Species seen, but not established - Loxosceles Brown, Chilean, and Mediterranean recluses found in Florida, but very uncommon. Also called Violin or Fiddleback Spider. A brown spider no larger than a quarter, with a dark brown violin shape on its back. Has six eyes. Bite: Red rings around black blister, appears infected. Swollen & painful. Takes a long " " time to heal completely. Fever, chills, nausea Closeup of the fiddle and vomiting, itching, brown urine. marking and six eyes Cleanse with soap & water. Emergency department or physician for tetanus booster or wound treatment if needed. Scorpions - 3 species found in Florida Florida bark, Guiana striped, Hentz striped Lobster-shaped brown or black body with a stinger on tail. Florida scorpions are NOT deadly venomous. But stings can cause pain and possible adverse allergic reactions. " Cleanse with soap & water. Apply ice. Quick Florida Tick Guide Lone Star Tick - Amblyomma americanum Larvae: June-November Nymphs: February-October Adults: April-August (peak in July) Diseases: Ehrlichiosis/Anaplasmosis, STARI, Tularemia " American Dog Tick - Dermacentor variabilis Larvae: July-February Nymphs: January-March Adults: March-September " Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Tularemia Black-Legged/Deer Tick - Ixodes scapularis April-August: Larvae and Nymphs September-May: Adults Diseases: Lyme Disease, Babesiosis, Human anaplasmosis " Gulf Coast Tick - Amblyomma maculatum Nymphs: February-August Adults: March-November Diseases: Rickettsia parkeri " Brown Dog Tick - Rickettsia parkeri Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever " Always check for ticks ASAP before they have time to attach. -

Appendix A: Consultation and Coordination

APPENDIX A: CONSULTATION AND COORDINATION Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease This page intentionally left blank Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-1 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-2 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-3 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-4 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-5 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-6 APPENDIX B: PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease This page intentionally left blank Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease B-1 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease B-2 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease B-3 APPENDIX C: VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE ASSESSMENTS Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE ASSESSMENTS FOR THE CANEEL BAY RESORT LEASE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT AT VIRGIN ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK ST. JOHN, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS Prepared for: National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta, Georgia March 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF ATTACHMENTS ...................................................................................................... -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Sistema De Clasificación Artificial De Las Magnoliatas Sinántropas De Cuba

Sistema de clasificación artificial de las magnoliatas sinántropas de Cuba. Pedro Pablo Herrera Oliver Tesis doctoral de la Univerisdad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2007 Sistema de clasificación artificial de las magnoliatas sinántropas de Cuba. Pedro Pablo Herrera Oliver PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO COOPERADO DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE: MANEJOS FORESTAL Y TURÍSTICO UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE, ESPAÑA UNIVERSIDAD DE PINAR DEL RÍO, CUBA TESIS EN OPCIÓN AL GRADO CIENTÍFICO DE DOCTOR EN CIENCIAS SISTEMA DE CLASIFICACIÓN ARTIFICIAL DE LAS MAGNOLIATAS SINÁNTROPAS DE CUBA Pedro- Pabfc He.r retira Qltver CUBA 2006 Tesis doctoral de la Univerisdad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2007 Sistema de clasificación artificial de las magnoliatas sinántropas de Cuba. Pedro Pablo Herrera Oliver PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO COOPERADO DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE: MANEJOS FORESTAL Y TURÍSTICO UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE, ESPAÑA Y UNIVERSIDAD DE PINAR DEL RÍO, CUBA TESIS EN OPCIÓN AL GRADO CIENTÍFICO DE DOCTOR EN CIENCIAS SISTEMA DE CLASIFICACIÓN ARTIFICIAL DE LAS MAGNOLIATAS SINÁNTROPAS DE CUBA ASPIRANTE: Lie. Pedro Pablo Herrera Oliver Investigador Auxiliar Centro Nacional de Biodiversidad Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática Ministerio de Ciencias, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente DIRECTORES: CUBA Dra. Nancy Esther Ricardo Ñapóles Investigador Titular Centro Nacional de Biodiversidad Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática Ministerio de Ciencias, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente ESPAÑA Dr. Andreu Bonet Jornet Piiofesjar Titular Departamento de EGdfegfe Universidad! dte Mearte CUBA 2006 Tesis doctoral de la Univerisdad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2007 Sistema de clasificación artificial de las magnoliatas sinántropas de Cuba. Pedro Pablo Herrera Oliver I. INTRODUCCIÓN 1 II. ANTECEDENTES 6 2.1 Historia de los esquemas de clasificación de las especies sinántropas (1903-2005) 6 2.2 Historia del conocimiento de las plantas sinantrópicas en Cuba 14 III. -

Solomon J.Pdf

EVALUATION OF CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL CONTROL STRATEGIES ACROSS LIFE HISTORY STAGES OF THE INVASIVE Kalanchoe xhoughtonii By JESSICA L. SOLOMON A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 Jessica L. Solomon To my mom and brother ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express the utmost gratitude to my advisor Dr. Stephen Enloe, for his compassion, support, knowledge, and passion in this research. Dr. Enloe has been a mentor in the field of research, education, and outreach. His energy helped inspire me in times I lacked the motivation and his kindness and support helped me through times of difficulty. I am also thankful for my committee members, Dr. Jay Ferrell and Dr. Carrie Reinhardt Adams for their support, time, and guidance. I would also like to extend immense gratitude towards my lab mates Jonathan Glueckert and Kaitlyn Quincy for all of their encouragement, friendship, and tutoring through our coursework and research. I am especially thankful for my lab mate Mackenzie Bell, who has been an incredibly supportive friend, science partner, and plant enthusiast with me for the past three years. I would also like to thank Lara Colley, Dr. James Leary, Dr. Benjamin Sperry, and the rest of the faculty at The Center of Aquatic and Invasive Center (CAIP) for their insight and passion for research and education. A special thank you is needed for Sara Humphrey, Conrad Oberweger, Ethan Church, and Matt Shinego who supports CAIP on a day- to-day basis. -

SFRC T-593 Phenology of Flowering and Fruiting

Report T-593 Phenology of Flowering an Fruiting In Pia t Com unities of Everglades NP and Biscayne N , orida RESOURCE MANAGEMENT EVERGLi\DES NATIONAL PARK BOX 279 NOMESTEAD, FLORIDA 33030 Everglades National Park, South Florida Research Center, P.O. Box 279, Homestead, Florida 33030 PHENOLOGY OF FLOWERING AND FRUITING IN PLANT COMMUNITIES OF EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK AND BISCAYNE NATIONAL MONUMENT, FLORIDA Report T - 593 Lloyd L. Loope U.S. National P ark Service South Florida Research Center Everglades National Park Homestead, Florida 33030 June 1980 Loope, Lloyd L. 1980. Phenology of Flowering and Fruiting in Plant Communities of Everglades National Park and Biscayne National Monument, Florida. South Florida Research Center Report T - 593. 50 pp. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES • ii LIST OF FIGU RES iv INTRODUCTION • 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. • 1 METHODS. • • • • • • • 1 CLIMATE AND WATER LEVELS FOR 1978 •• . 3 RESULTS ••• 3 DISCUSSION. 3 The need and mechanisms for synchronization of reproductive activity . 3 Tropical hardwood forest. • • 5 Freshwater wetlands 5 Mangrove vegetation 6 Successional vegetation on abandoned farmland. • 6 Miami Rock Ridge pineland. 7 SUMMARY ••••• 7 LITERATURE CITED 8 i LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Climatic data for Homestead Experiment Station, 1978 . • . • . • . • . • . • . 10 Table 2. Climatic data for Tamiami Trail at 40-Mile Bend, 1978 11 Table 3. Climatic data for Flamingo, 1978. • • • • • • • • • 12 Table 4. Flowering and fruiting phenology, tropical hardwood hammock, area of Elliott Key Marina, Biscayne National Monument, 1978 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 14 Table 5. Flowering and fruiting phenology, tropical hardwood hammock, Bear Lake Trail, Everglades National Park (ENP), 1978 • . • . • . 17 Table 6. Flowering and fruiting phenology, tropical hardwood hammock, Mahogany Hammock, ENP, 1978. -

Evolução Cromossômica Em Plantas De Inselbergues Com Ênfase Na Família Apocynaceae Juss. Angeline Maria Da Silva Santos

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA PARAÍBA CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS AGRÁRIAS PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM AGRONOMIA CAMPUS II – AREIA-PB Evolução cromossômica em plantas de inselbergues com ênfase na família Apocynaceae Juss. Angeline Maria Da Silva Santos AREIA - PB AGOSTO 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA PARAÍBA CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS AGRÁRIAS PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM AGRONOMIA CAMPUS II – AREIA-PB Evolução cromossômica em plantas de inselbergues com ênfase na família Apocynaceae Juss. Angeline Maria Da Silva Santos Orientador: Prof. Dr. Leonardo Pessoa Felix Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Agronomia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Centro de Ciências Agrárias, Campus II Areia-PB, como parte integrante dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Doutor em Agronomia. AREIA - PB AGOSTO 2017 Catalogação na publicação Seção de Catalogação e Classificação S237e Santos, Angeline Maria da Silva. Evolução cromossômica em plantas de inselbergues com ênfase na família Apocynaceae Juss. / Angeline Maria da Silva Santos. - Areia, 2017. 137 f. : il. Orientação: Leonardo Pessoa Felix. Tese (Doutorado) - UFPB/CCA. 1. Afloramentos. 2. Angiospermas. 3. Citogenética. 4. CMA/DAPI. 5. Ploidia. I. Felix, Leonardo Pessoa. II. Título. UFPB/CCA-AREIA A Deus, pela presença em todos os momentos da minha vida, guiando-me a cada passo dado. À minha família Dedico esta conquista aos meus pais Maria Geovânia da Silva Santos e Antonio Belarmino dos Santos (In Memoriam), irmãos Aline Santos e Risomar Nascimento, tios Josimar e Evania Oliveira, primos Mayara Oliveira e Francisco Favaro, namorado José Lourivaldo pelo amor a mim concedido e por me proporcionarem paz na alma e felicidade na vida. Em especial à minha mãe e irmãos por terem me ensinado a descobrir o valor da disciplina, da persistência e da responsabilidade, indispensáveis para a construção e conquista do meu projeto de vida. -

Global Seagrass Distribution and Diversity: a Bioregional Model ⁎ F

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 350 (2007) 3–20 www.elsevier.com/locate/jembe Global seagrass distribution and diversity: A bioregional model ⁎ F. Short a, , T. Carruthers b, W. Dennison b, M. Waycott c a Department of Natural Resources, University of New Hampshire, Jackson Estuarine Laboratory, Durham, NH 03824, USA b Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Cambridge, MD 21613, USA c School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, Townsville, 4811 Queensland, Australia Received 1 February 2007; received in revised form 31 May 2007; accepted 4 June 2007 Abstract Seagrasses, marine flowering plants, are widely distributed along temperate and tropical coastlines of the world. Seagrasses have key ecological roles in coastal ecosystems and can form extensive meadows supporting high biodiversity. The global species diversity of seagrasses is low (b60 species), but species can have ranges that extend for thousands of kilometers of coastline. Seagrass bioregions are defined here, based on species assemblages, species distributional ranges, and tropical and temperate influences. Six global bioregions are presented: four temperate and two tropical. The temperate bioregions include the Temperate North Atlantic, the Temperate North Pacific, the Mediterranean, and the Temperate Southern Oceans. The Temperate North Atlantic has low seagrass diversity, the major species being Zostera marina, typically occurring in estuaries and lagoons. The Temperate North Pacific has high seagrass diversity with Zostera spp. in estuaries and lagoons as well as Phyllospadix spp. in the surf zone. The Mediterranean region has clear water with vast meadows of moderate diversity of both temperate and tropical seagrasses, dominated by deep-growing Posidonia oceanica. -

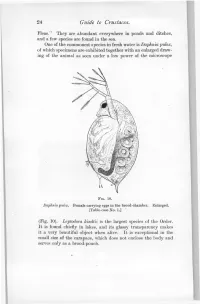

24 Guide to Crustacea

24 Guide to Crustacea. Fleas." They are abundant everywhere in ponds and ditches, and a few species are found in the sea. One of the commonest species in fresh water is Daphnia pulex, of which specimens are exhibited together with an enlarged draw- ing of the animal as seen under a low power of the microscope FIG. 10. Daphnia pulex. Female carrying eggs in the brood-chamber. Enlarged. [Table-case No. 1.] (Fig. 10). Leptodora kindtii is the largest species of the Order. It is found chiefly in lakes, and its glassy transparency makes it a very beautiful object when alive. It is exceptional in the small size of the carapace, which does not enclose the body and serves only as a brood-pouch. Ostracoda. 25 Sub-class II.—OSTRACODA. (Table-ease No. 1.) The number of somites, as indicated by the appendages, is smaller than in any other Crustacea, there being, at most, only two pairs of trunk-limbs behind those belonging to the head- region. The carapace forms a bivalved shell completely en- closing the body and limbs. There is a large, and often leg-like, palp on the mandible. The antennules and antennae are used for creeping or swimming. The Ostracoda (Fig. 10) are for the most part extremely minute animals, and only one or two of the larger species can be exhibited. They occur abundantly in fresh water and in FIG. 11. Shells of Ostracoda, seen from the side. A. Philomedes brenda (Myodocopa) ; B. Cypris fuscata (Podocopa); ('. Cythereis ornata (Podocopa): all much enlarged, n., Notch characteristic of the Myodocopa; e., the median eye ; a., mark of attachment of the muscle connecting the two valves of the shell. -

Karyotype Variations in Seagrass (Halodule Wrightii Ascherson¬タヤ

Aquatic Botany 136 (2017) 52–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Aquatic Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aquabot Short communication Karyotype variations in seagrass (Halodule wrightii Ascherson—Cymodoceaceae) a b,∗ a Silmar Luiz da Silva , Karine Matos Magalhães , Reginaldo de Carvalho a Graduate Program in Botany—PPGB and Cytogenetic Plant Laboratory of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, Rua Dom Manoel de Medeiros, s/n, Dois Irmãos, CEP: 52171-900, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil b Aquatic Ecosystems Laboratory of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, Rua Dom Manoel de Medeiros, s/n, Dois Irmãos, CEP: 52171-900, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Karyotype variations in plants are common, but the results of cytological studies of some seagrasses Received 26 June 2015 remain unclear. The nature of the variation is not clearly understood, and the basic chromosomal num- Received in revised form 5 August 2016 ber has still not been established for the majority of the species. Here, we describe karyotype variations in Accepted 15 September 2016 the seagrass Halodule wrightii, and we suggest potentially causative mechanisms involving cytomixis and Available online 16 September 2016 B chromosomes. We prepared slides using the squashing technique followed by conventional Giemsa and C-banding, and silver nitrate and a CMA/DAPI staining. Based on intraspecific analysis, the diploid chromo- Keywords: some number of H. wrightii exhibited a variation from 2n = 24 to 2n = 39; 2n = 38 was the most frequent. In Cytomixis Seagrass general, we characterized the karyotype as an asymmetrical, semi-reticulated interphase nucleus with a chromosomally uniform condensation pattern. -

Native Trees of Mexico: Diversity, Distribution, Uses and Conservation

Native trees of Mexico: diversity, distribution, uses and conservation Oswaldo Tellez1,*, Efisio Mattana2,*, Mauricio Diazgranados2, Nicola Kühn2, Elena Castillo-Lorenzo2, Rafael Lira1, Leobardo Montes-Leyva1, Isela Rodriguez1, Cesar Mateo Flores Ortiz1, Michael Way2, Patricia Dávila1 and Tiziana Ulian2 1 Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Av. De los Barrios 1, Los Reyes Iztacala Tlalnepantla, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Estado de México, Mexico 2 Wellcome Trust Millennium Building, RH17 6TN, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Ardingly, West Sussex, United Kingdom * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Background. Mexico is one of the most floristically rich countries in the world. Despite significant contributions made on the understanding of its unique flora, the knowledge on its diversity, geographic distribution and human uses, is still largely fragmented. Unfortunately, deforestation is heavily impacting this country and native tree species are under threat. The loss of trees has a direct impact on vital ecosystem services, affecting the natural capital of Mexico and people's livelihoods. Given the importance of trees in Mexico for many aspects of human well-being, it is critical to have a more complete understanding of their diversity, distribution, traditional uses and conservation status. We aimed to produce the most comprehensive database and catalogue on native trees of Mexico by filling those gaps, to support their in situ and ex situ conservation, promote their sustainable use, and inform reforestation and livelihoods programmes. Methods. A database with all the tree species reported for Mexico was prepared by compiling information from herbaria and reviewing the available floras. Species names were reconciled and various specialised sources were used to extract additional species information, i.e. -

Cleto Sánchez Falcón” Y “M

34 NOVITATES CARIBAEA 4: 34-44, 2011 MATERIAL TIPO DEPOSITADO EN LAS COLECCIONES MALACOLÓGICAS HISTÓRICAS “CLETO SÁNCHEZ FALCÓN” Y “M. L. JAUME” EN SANTIAGO DE CUBA, CUBA Beatriz Lauranzón Meléndez1, David Maceira Filgueira1 y Margarita Moran Zambrano2. 1Centro Oriental de Ecosistemas y Biodiversidad. BIOECO. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba [email protected] 2Museo “Jorge Ramón Cuevas”, Reserva de Biosfera Baconao. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba RESUMEN Fueron revisadas las colecciones malacológicas históricas “Cleto Sánchez Falcón” y “M. L. Jaume”, depositadas en el Museo de Historia Natural “Tomás Romay” y el Museo “Jorge Ramón Cuevas”. De ambas colecciones se copiaron los datos de etiqueta del material tipo. La validez de la información de etiqueta para cada lote fue revisada con las descripciones originales correspondientes a cada especie, revisiones taxonómicas de familias y catálogos actualizados. Se registraron 434 ejemplares, incluidos en 56 subespecies, 34 especies y seis (6) familias; estos se corresponden con 85 localidades y 16 colectores. La colección “Cleto Sánchez Falcón” posee 368 ejemplares de las familias Annulariidae, Cerionidae, Megalomastomidae, Helicinidae, Orthalicidae y Urocoptidae, siendo esta última la más representada. La colección “M. L. Jaume” tiene 66 ejemplares de 36 subespecies de Liguus fasciatus (Müller), Orthalicidae. Palabras clave: moluscos terrestres, material tipo, colección histórica, Cuba. ABSTRACT The historic malacological collections “Cleto Sánchez Falcón” and “M. L. Jaume” housed in the Museo de Historia Natural “Tomás Romay” and Museo “Jorge Ramón Cuevas” were revised, and the label data of type material was copied. The validity of the information on labels for each lot was revised with the original descriptions for all species, taxonomic revisions of families and updated catalogues.