Efficiency and the Bear: Short Sales and Markets Around the World*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Short Sellers and Financial Misconduct 6 7 ∗ 8 JONATHAN M

jofi˙1597 jofi2009v2.cls (1994/07/13 v1.2u Standard LaTeX document class) June 25, 2010 19:56 JOFI jofi˙1597 Dispatch: June 25, 2010 CE: AFL Journal MSP No. No. of pages: 35 PE: Beetna 1 THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE • VOL. LXV, NO. 5 • OCTOBER 2010 2 3 4 5 Short Sellers and Financial Misconduct 6 7 ∗ 8 JONATHAN M. KARPOFF and XIAOXIA LOU 9 10 ABSTRACT 11 12 We examine whether short sellers detect firms that misrepresent their financial state- ments, and whether their trading conveys external costs or benefits to other investors. 13 Abnormal short interest increases steadily in the 19 months before the misrepresen- 14 tation is publicly revealed, particularly when the misconduct is severe. Short selling 15 is associated with a faster time-to-discovery, and it dampens the share price inflation 16 that occurs when firms misstate their earnings. These results indicate that short sell- 17 ers anticipate the eventual discovery and severity of financial misconduct. They also convey external benefits, helping to uncover misconduct and keeping prices closer to 18 fundamental values. 19 20 21 22 SHORT SELLING IS A CONTROVERSIAL ACTIVITY. Detractors claim that short sell- 23 ers undermine investors’ confidence in financial markets and decrease market 24 liquidity. For example, a short seller can spread false rumors about a firm 25 in which he has a short position and profit from the resulting decline in the 1 26 stock price. Advocates, in contrast, argue that short selling facilitates market 27 efficiency and the price discovery process. Investors who identify overpriced 28 firms can sell short, thereby incorporating their unfavorable information into 29 market prices. -

Asset Securitization

L-Sec Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Asset Securitization Comptroller’s Handbook November 1997 L Liquidity and Funds Management Asset Securitization Table of Contents Introduction 1 Background 1 Definition 2 A Brief History 2 Market Evolution 3 Benefits of Securitization 4 Securitization Process 6 Basic Structures of Asset-Backed Securities 6 Parties to the Transaction 7 Structuring the Transaction 12 Segregating the Assets 13 Creating Securitization Vehicles 15 Providing Credit Enhancement 19 Issuing Interests in the Asset Pool 23 The Mechanics of Cash Flow 25 Cash Flow Allocations 25 Risk Management 30 Impact of Securitization on Bank Issuers 30 Process Management 30 Risks and Controls 33 Reputation Risk 34 Strategic Risk 35 Credit Risk 37 Transaction Risk 43 Liquidity Risk 47 Compliance Risk 49 Other Issues 49 Risk-Based Capital 56 Comptroller’s Handbook i Asset Securitization Examination Objectives 61 Examination Procedures 62 Overview 62 Management Oversight 64 Risk Management 68 Management Information Systems 71 Accounting and Risk-Based Capital 73 Functions 77 Originations 77 Servicing 80 Other Roles 83 Overall Conclusions 86 References 89 ii Asset Securitization Introduction Background Asset securitization is helping to shape the future of traditional commercial banking. By using the securities markets to fund portions of the loan portfolio, banks can allocate capital more efficiently, access diverse and cost- effective funding sources, and better manage business risks. But securitization markets offer challenges as well as opportunity. Indeed, the successes of nonbank securitizers are forcing banks to adopt some of their practices. Competition from commercial paper underwriters and captive finance companies has taken a toll on banks’ market share and profitability in the prime credit and consumer loan businesses. -

Hedge Funds Oversight, Report of the Technical Committee Of

Hedge Funds Oversight Consultation Report TECHNICAL COMMITTEE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF SECURITIES COMMISSIONS MARCH 2009 This paper is for public consultation purposes only. It has not been approved for any other purpose by the IOSCO Technical Committee or any of its members. Foreword The IOSCO Technical Committee has published for public comment this consultation report on Hedge Funds Oversight. The Report makes preliminary recommendations of regulatory approaches that may be used to mitigate the regulatory risks posed by hedge funds. The Report will be finalised after consideration of comments received from the public. How to Submit Comments Comments may be submitted by one of the three following methods on or before 30 April 2009. To help us process and review your comments more efficiently, please use only one method. 1. E-mail • Send comments to Greg Tanzer, Secretary General, IOSCO at the following email address: [email protected] • The subject line of your message should indicate “Public Comment on the Hedge Funds Oversight: Consultation Report”. • Please do not submit any attachments as HTML, GIF, TIFF, PIF or EXE files. OR 2. Facsimile Transmission Send a fax for the attention of Greg Tanzer using the following fax number: + 34 (91) 555 93 68. OR 3. Post Send your comment letter to: Greg Tanzer Secretary General IOSCO 2 C / Oquendo 12 28006 Madrid Spain Your comment letter should indicate prominently that it is a “Public Comment on the Hedge Funds Oversight: Consultation Report” Important: All comments will be made available publicly, unless anonymity is specifically requested. Comments will be converted to PDF format and posted on the IOSCO website. -

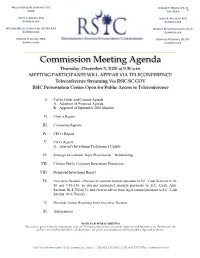

2020.12.03 RSIC Meeting Materials

WILLIAM (BILL) H. HANCOCK, CPA RONALD P. WILDER, PH. D CHAIR VICE-CHAIR 1 PEGGY G. BOYKIN, CPA ALLEN R. GILLESPIE, CFA COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER WILLIAM (BILL) J. CONDON, JR. JD, MA, CPA REBECCA M. GUNNLAUGSSON, PH. D COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER EDWARD N. GIOBBE, MBA REYNOLDS WILLIAMS, JD, CFP COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER _____________________________________________________________________________________ Commission Meeting Agenda Thursday, December 3, 2020 at 9:30 a.m. MEETING PARTICIPANTS WILL APPEAR VIA TELECONFERENCE Teleconference Streaming Via RSIC.SC.GOV RSIC Presentation Center Open for Public Access to Teleconference I. Call to Order and Consent Agenda A. Adoption of Proposed Agenda B. Approval of September 2020 Minutes II. Chair’s Report III. Committee Reports IV. CEO’s Report V. CIO’s Report A. Quarterly Investment Performance Update VI. Strategic Investment Topic Presentation – Rebalancing VII. Chinese Public Company Investment Discussion VIII. Delegated Investment Report IX. Executive Session – Discuss investment matters pursuant to S.C. Code Sections 9-16- 80 and 9-16-320; to discuss personnel matters pursuant to S.C. Code Ann. Section 30-4-70(a)(1); and receive advice from legal counsel pursuant to S.C. Code Section 30-4-70(a)(2). X. Potential Action Resulting from Executive Session XI. Adjournment NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING This notice is given to meet the requirements of the S.C. Freedom of Information Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Furthermore, this facility is accessible to individuals with disabilities, and special accommodations will be provided if requested in advance. 1201 MAIN STREET, SUITE 1510, COLUMBIA, SC 29201 // (P) 803.737.6885 // (F) 803.737.7070 // WWW.RSIC.SC.GOV 2 AMENDED DRAFT South Carolina Retirement System Investment Commission Meeting Minutes September 10, 2020 9:30 a.m. -

Corporate Venturing Managing the Innovation Family in a Dynamic World

corporate venturing Managing the innovation family in a dynamic world Corina Kuiper Fred van Ommen Copyright page VOC Uitgevers Postal Box 366 6500 AJ Nijmegen www.voc-uitgevers.nl Design & lay-out mw:ontwerp, Nijmegen Production Rocim, Oosterbeek ISBN 978-90-79812-17-2 NUR 800 First printing, March 2015 All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the Publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. This publication has been made possible by a generous dotation from Corporate Venturing Network Netherlands (CVNN). Table of Contents Preface 5 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Corporate Venturing: Go Dutch 7 1.2 Corporate Venturing Network Netherlands (CVNN) 9 1.3 About this book 14 2 Corporate Venturing – Principles 15 2.1 Corporate Venturing: a contradiction in terms 15 2.2 Corporate Venturing has become a necessity: live or die 17 2.3 Waves of Corporate Venturing 21 2.4 Different flavours of Corporate Venturing 27 2.5 Granularity of Innovation: the Innovation family 47 2.6 Managing the generation gap: the differences in behaviour 53 2.7 The five levels of Corporate Venturing 67 2.8 Entrepreneurship: causation versus effectuation 81 3 Corporate Venturing – In practice 91 3.1 AGC Asahi glass 92 3.2 ASML – Fulfilling the potential of semiconductor lithography 98 3.3 Bekaert – Better Together 104 3.4 Brightlands Chemelot Campus – Chemistry connects people 110 3.5 DPI (Dutch Polymer Institute) & DPI Value Centre 119 3.6 DSM - Bright -

Hedge Fund Performance During the Internet Bubble Bachelor Thesis Finance

Hedge fund performance during the Internet bubble Bachelor thesis finance Colby Harmon 6325661 /10070168 Thesis supervisor: V. Malinova 1 Table of content 1. Introduction p. 3 2. Literature reviews of studies on mutual funds and hedge funds p. 5 2.1 Evolution of performance measures p. 5 2.2 Studies on performance of mutual and hedge funds p. 6 3. Deficiencies in peer group averages p. 9 3.1 Data bias when measuring the performance of hedge funds p. 9 3.2 Short history of hedge fund data p. 10 3.3 Choice of weight index p. 10 4. Hedge fund strategies p. 12 4.1 Equity hedge strategies p. 12 4.1.1 Market neutral strategy p. 12 4.2 Relative value strategies p. 12 4.2.1 Fixed income arbitrage p. 12 4.2.2 Convertible arbitrage p. 13 4.3 Event driven strategies p. 13 4.3.1 Distressed securities p. 13 4.3.2 Merger arbitrage p. 14 4.4 Opportunistic strategies p. 14 4.4.1 Global macro p. 14 4.5 Managed futures p. 14 4.5.1 Trend followers p. 15 4.6 Recent performance of different strategies p. 15 5. Data description p. 16 6. Methodology p. 18 6.1 Seven factor model description p. 18 6.2 Hypothesis p. 20 7. Results p. 21 7.1 Results period 1997-2000 p. 21 7.2 Results period 2000-2003 p. 22 8. Discussion of results p. 23 9. Conclusion p. 24 2 1. Introduction A day without Internet today would be cruel and unthinkable. -

Arbitrage Pricing Theory∗

ARBITRAGE PRICING THEORY∗ Gur Huberman Zhenyu Wang† August 15, 2005 Abstract Focusing on asset returns governed by a factor structure, the APT is a one-period model, in which preclusion of arbitrage over static portfolios of these assets leads to a linear relation between the expected return and its covariance with the factors. The APT, however, does not preclude arbitrage over dynamic portfolios. Consequently, applying the model to evaluate managed portfolios contradicts the no-arbitrage spirit of the model. An empirical test of the APT entails a procedure to identify features of the underlying factor structure rather than merely a collection of mean-variance efficient factor portfolios that satisfies the linear relation. Keywords: arbitrage; asset pricing model; factor model. ∗S. N. Durlauf and L. E. Blume, The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, forthcoming, Palgrave Macmillan, reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan. This article is taken from the authors’ original manuscript and has not been reviewed or edited. The definitive published version of this extract may be found in the complete The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics in print and online, forthcoming. †Huberman is at Columbia University. Wang is at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the McCombs School of Business in the University of Texas at Austin. The views stated here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Introduction The Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT) was developed primarily by Ross (1976a, 1976b). It is a one-period model in which every investor believes that the stochastic properties of returns of capital assets are consistent with a factor structure. -

Securitization & Hedge Funds

SECURITIZATION & HEDGE FUNDS: COLLATERALIZED FUND OBLIGATIONS SECURITIZATION & HEDGE FUNDS: CREATING A MORE EFFICIENT MARKET BY CLARK CHENG, CFA Intangis Funds AUGUST 6, 2002 INTANGIS PAGE 1 SECURITIZATION & HEDGE FUNDS: COLLATERALIZED FUND OBLIGATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 3 PROBLEM.................................................................................................................................................... 4 SOLUTION................................................................................................................................................... 5 SECURITIZATION..................................................................................................................................... 5 CASH-FLOW TRANSACTIONS............................................................................................................... 6 MARKET VALUE TRANSACTIONS.......................................................................................................8 ARBITRAGE................................................................................................................................................ 8 FINANCIAL ENGINEERING.................................................................................................................... 8 TRANSPARENCY...................................................................................................................................... -

The Impact of Capital Market on the Economic Growth in Oman

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Alam, Md. Shabbir; Hussein, Muawya Ahmed Article The impact of capital market on the economic growth in Oman Financial Studies Provided in Cooperation with: "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), Romanian Academy Suggested Citation: Alam, Md. Shabbir; Hussein, Muawya Ahmed (2019) : The impact of capital market on the economic growth in Oman, Financial Studies, ISSN 2066-6071, Romanian Academy, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, Bucharest, Vol. 23, Iss. 2 (84), pp. 117-129 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231680 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

A Primer on Modern Monetary Theory

2021 A Primer on Modern Monetary Theory Steven Globerman fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive Summary / i 1. Introducing Modern Monetary Theory / 1 2. Implementing MMT / 4 3. Has Canada Adopted MMT? / 10 4. Proposed Economic and Social Justifications for MMT / 17 5. MMT and Inflation / 23 Concluding Comments / 27 References / 29 About the author / 33 Acknowledgments / 33 Publishing information / 34 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 35 Purpose, funding, and independence / 35 About the Fraser Institute / 36 Editorial Advisory Board / 37 fraserinstitute.org fraserinstitute.org Executive Summary Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a policy model for funding govern- ment spending. While MMT is not new, it has recently received wide- spread attention, particularly as government spending has increased dramatically in response to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and concerns grow about how to pay for this increased spending. The essential message of MMT is that there is no financial constraint on government spending as long as a country is a sovereign issuer of cur- rency and does not tie the value of its currency to another currency. Both Canada and the US are examples of countries that are sovereign issuers of currency. In principle, being a sovereign issuer of currency endows the government with the ability to borrow money from the country’s cen- tral bank. The central bank can effectively credit the government’s bank account at the central bank for an unlimited amount of money without either charging the government interest or, indeed, demanding repayment of the government bonds the central bank has acquired. In 2020, the cen- tral banks in both Canada and the US bought a disproportionately large share of government bonds compared to previous years, which has led some observers to argue that the governments of Canada and the United States are practicing MMT. -

Neo-Liberalism As Financialisation1 Engaging Neo-Liberalism When It

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online Neo-liberalism as Financialisation 1 Engaging Neo-liberalism When it first emerged, neo-liberalism seemed to be able to be defined relatively easily and uncontroversially. In the economic arena, the contrast could be made with Keynesianism and emphasis placed on perfectly working markets. A correspondingly distinctive stance could be made over the role of the state as corrupt, rent-seeking and inefficient as opposed to benevolent and progressive. Ideologically, the individual pursuit of self-interest as the means to freedom was offered in contrast to collectivism. And, politically, Reaganism and Thatcherism came to the fore. It is also significant that neo-liberalism should emerge soon after the post-war boom came to an end, together with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. This is all thirty or more years ago and, whilst neo-liberalism has entered the scholarly if not popular lexicon, it is now debatable whether it is now or, indeed, ever was clearly defined. How does it fair alongside globalisation, the new world order, and the new imperialism, for example, as descriptors of contemporary capitalism. Does each of these refer to a similar understanding but with different terms and emphasis? And how do we situate neo-liberalism in relation to Third Wayism, the social market, and so on, whose politicians, theorists and ideologues would pride themselves as departing from neo- liberalism but who, in their politics and policies, seem at least in part to have been captured by it (and even vice-versa in some instances)? These conundrums in the understanding and nature of neo-liberalism have been highlighted by James Ferguson (2007) who reveals how what would traditionally be termed progressive policies (a basic income grant for example) have been rationalised through neo-liberal discourse. -

Scope and Function of the Capital Market in the American Economy

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Flow of Capital Funds in the Postwar Economy Volume Author/Editor: Raymond W. Goldsmith Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-870-14112-0 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gold65-1 Publication Date: 1965 Chapter Title: Scope and Function of the Capital Market in the American Economy Chapter Author: Raymond W. Goldsmith Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c1680 Chapter pages in book: (p. 22 - 42) CHAPTER 1 Scope and Function of the Capital Market in the American Economy Origin of the Capital Market in the Separation of Saving and Investment A MARKET for new capital, apart from transactions in existing finan- cial and real assets, exists because in a modern economy saving (the excess of current income over current expenditures on consumption) is to a large extent separated from investment, i.e., expenditures on durable assets usually defined as new construction, equipment, and additionstoinventories and excluding education,research, and health.1 In any given period every economic unit either saves or dissaves— if we ignore the relatively few units whose current expenditures ex- actly balance their current income; and most units make capital expenditures, which usually involve payments to other units for fin- ished durable goods, materials, or labor, but which may also be internal and imputed (e.g., Crusoe building his boat). Both saving and investment may be calculated gross or net of capital consumption allowances or retirements. Since these diminish saving and investment equally, the difference between saving and investment is the same whether calculated on a gross or net basis.