Lancaster and Morecambe Regional Planning Scheme (1927)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Blood Service-Lancaster

From From Kendal Penrith 006) Slyne M6 A5105 Halton A6 Morecambe B5273 A683 Bare Bare Lane St Royal Lancaster Infirmary Morecambe St J34 Ashton Rd, Lancaster LA1 4RP Torrisholme Tel: 0152 489 6250 Morecambe West End A589 Fax: 0152 489 1196 Bay A589 Skerton A683 A1 Sandylands B5273 A1(M) Lancaster A65 A59 York Castle St M6 A56 Lancaster Blackpool Blackburn Leeds M62 Preston PRODUCED BY BUSINESS MAPS LTD FROM DIGITAL DATA - BARTHOLOMEW(2 M65 Heysham M62 A683 See Inset A1 M61 M180 Heaton M6 Manchester M1 Aldcliffe Liverpool Heysham M60 Port Sheffield A588 e From the M6 Southbound n N Exit the motorway at junction 34 (signed Lancaster, u L Kirkby Lonsdale, Morecambe, Heysham and the A683). r Stodday A6 From the slip road follow all signs to Lancaster. l e Inset t K A6 a t v S in n i Keep in the left hand lane of the one way system. S a g n C R e S m r At third set of traffic lights follow road round to the e t a te u h n s Q r a left. u c h n T La After the car park on the right, the one way system t S bends to the left. A6 t n e Continue over the Lancaster Canal, then turn right at g e Ellel R the roundabout into the Royal Lancaster Infirmary (see d R fe inset). if S cl o d u l t M6 A h B5290 R From the M6 Northbound d Royal d Conder R Exit the motorway at junction 33 (signed Lancaster). -

Construction Traffic Management Plan

Haweswater Aqueduct Resilience Programme Construction Traffic Management Plan Proposed Marl Hill and Bowland Sections Access to Bonstone, Braddup and Newton-in-Bowland compounds Option 1 - Use of the Existing Ribble Crossings Project No: 80061155 Projectwise Ref: 80061155-01-UU-TR4-XX-RP-C-00012 Planning Ref: RVBC-MH-APP-007_01 Version Purpose / summary of Date Written By Checked By Approved By changes 0.1 02.02.21 TR - - P01 07.04.21 TR WB ON 0.2 For planning submission 14.06.21 AS WB ON Copyright © United Utilities Water Limited 2020 1 Haweswater Aqueduct Resilience Programme Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1.1 The Haweswater Aqueduct ......................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 The Bowland Section .................................................................................................. 4 1.1.3 The Marl Hill Section................................................................................................... 4 1.1.4 Shared access ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Purpose of the Document .................................................................................................. 4 2. Sequencing of proposed works and anticipated -

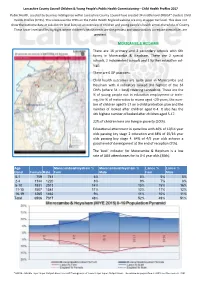

MORECAMBE & HEYSHAM There Are 16 Primary and 2 Secondary

Lancashire County Council Children & Young People’s Public Health Commissioning—Child Health Profiles 2017 Public Health, assisted by Business Intelligence within Lancashire County Council have created 34 middle level (MSOA* cluster) Child Health Profiles (CHPs). This is because the CHPs on the Public Health England website are only at upper tier level. This does not show the outcome data at sub-district level but just an overview of children and young people’s health across the whole of County. These lower level profiles highlight where children’s health needs are the greatest and opportunities to reduce inequalities are greatest. MORECAMBE & HEYSHAM There are 16 primary and 2 secondary schools with 6th forms in Morecambe & Heysham. There are 2 special schools, 2 independent schools and 1 further education col- lege. There are 6 GP practices. Child health outcomes are quite poor in Morecambe and Heysham with 4 indicators ranked 3rd highest of the 34 CHPs (where 34 = best) covering Lancashire. These are the % of young people not in education employment or train- ing, the % of maternities to mums aged <20 years, the num- ber of children aged 5-17 on a child protection plan and the number of looked after children aged 0-4. It also has the 4th highest number of looked after children aged 5-17. 22% of children here are living in poverty (10th). Educational attainment in quite low with 46% of 10/11 year olds passing key stage 2 education and 48% of 15/16 year olds passing key stage 4. 64% of 4/5 year olds achieve a good level of development at the end of reception (7th). -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

Appendix 5 Fylde

FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 LANCASTER - GARSTANG - POULTON - BLACKPOOL 42 via Galgate - Great Eccleston MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ LANCASTER Bus Station 1900 2015 2130 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 1909 2024 2139 LANCASTER University Gates 1912 2027 2142 GALGATE Crossroads 1915 2030 2145 CABUS Hamilton Arms 1921 2036 2151 GARSTANG Bridge Street 1926 2041 2156 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 1935 2050 2205 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 1939 2054 2209 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 1943 2058 2213 POULTON St Chads Church 1953 2108 2223 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 1958 2113 2228 BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2010 2125 2240 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council BLACKPOOL - POULTON - GARSTANG - LANCASTER 42 via Great Eccleston - Galgate MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2015 2130 2245 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 2020 2135 2250 POULTON Teanlowe Centre 2032 2147 2302 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 2042 2157 2312 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 2047 2202 2317 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 2051 2206 2321 GARSTANG Park Hill Road 2059 2214 2329 CABUS Hamilton Arms 2106 2221 2336 GALGATE Crossroads 2112 2227 2342 LANCASTER University Gates 2115 2230 2345 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 2118 2233 2348 LANCASTER Bus Station 2127 2242 2357 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council LIST OF ALTERNATIVE TRANSPORT SERVICES AVAILABLE – Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 2 between Lancaster and University Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 40 between Lancaster and Garstang (limited) Blackpool Transport Service 2 between Poulton and Blackpool FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 PRESTON - LYTHAM - ST. -

Newsletter June 2017

Newsletter Issue 7, June 2017 Head Office: North Road, Carnforth, Lancaster LA5 9LX T: 01524 734433 F: 01524 720050 Residential unit opens its doors Here at Hillcroft we are proud to announce the news but surrounded by the beautiful Lancashire that we are now expanding into residential care. countryside. With over 25 years of experience in nursing care and “With an aging population, there needs to be more 6 homes all located in the local area, the directors felt options available to people when they can no longer it was time to branch out into another type of service. stay at home. Offering residential care is an exciting We are trying to defy the national trend which has new step for us at Hillcroft and one we feel confident unfortunately seen many care homes close their doors we can deliver to the highest standard.” over the past year. The expansion follows Age UK estimating that more The expansion, which is at our Galgate home began than a million older people in England have been last year. living with unmet social care needs, such as not receiving assistance with bathing and dressing. The new unit, which opened earlier this month, is housed in a grade II listed building which has been The new unit at Galgate is separate from the nursing tastefully converted to offer the ideal environment for home and the care that will be provided will include those who need a bit of extra help with day-to-day assistance with meals, personal care and taking tasks. medication. Gill Reynolds, one of the Directors at Hillcroft said: It is important to us that no body feels deprived of “Hillcroft House in Galgate is the perfect location for their independence and that Hillcroft House feels those who need long-term care and would prefer to like their home. -

Peat Database Results Lancashire

Bare, Lancashire Record ID 236 Authors Year Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., 1998 Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. Location description Deposit location SD 443 649 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Peat layer (often <1 m thick, hard, consolidated, dry, laminated deposit). Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Boreholes SD46 SW/52-54 Depth of deposit 14C ages available -10 m OD No Notes Bibliographic reference Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. 1998 'Geology of the country around Lancaster', Memoir for 1:50,000 geological sheet 59 (England and Wales), . Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 31 Bare, Lancashire Record ID 237 Authors Year Crofton, A. 1876 Location description Deposit location SD 445 651 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Peat horizon resting on blue organic clay. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available No Notes Crofton (1876) referred to in Brandon et al (1998). Possibly same layer as mentioned by Reade (1904). Bibliographic reference Crofton, A. 1876 'Drift, peat etc. of Heysman [Heysham], Morecambe Bay', Transactions of the Manchester Geological Society, 14, 152-154. Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 2 of 31 Carnforth coastal area, Lancashire Record ID 245 Authors Year Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., 1998 Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. Location description Deposit location SD 4879 6987 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Coastal peat up to 4.9 m thick. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Borehole SD 46 NE/1 Depth of deposit 14C ages available Varying from near-surface to at-surface. -

Carnforth High School 13 May 2020..Pdf

Admissions Policy 2021/2022 Applications for admission to the school should be made online between 1st September 2020 and 31st October 2020 via the Local Authority website www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools. It is not normally possible to change the order of your preferences for schools after the closing date. Parents must complete the Local Authority electronic form, stating three preferences. The school is not able to offer places beyond its admission number (132). Offers of places under the equal preference system will be sent to parents on 1st March 2021 by the Local Authority. Parents of children not admitted will be offered an alternative place by the Local Authority. In the event the school is oversubscribed, a supplementary form is available from the school and the school’s website. The supplementary form should be returned to the school by 31st October 2020. If the school is oversubscribed, a failure to complete the supplementary form may result in your application for a place in this school being considered against a lower priority criteria. The number of places available for admission to Year 7 in September 2021 will be a maximum of 132. The Governing Body will not place any restrictions on admissions to Year 7 unless the number of children for whom admission is sought exceeds this number. The Governing Body operates a system of equal preferences under which they consider all preferences equally and the Local Authority notifies parents of the result. In the event that there are more applicants than places, after admitting all children with a Statement of Educational Need or Health and Care Plan naming this school, the Governing Body will allocate places using the criteria below, which are listed in order of priority: 1. -

Carnforth Conservation Area Appraisal

Carnforth Conservation Area Appraisal Adopted June 2014 Carnforth Conservation Area Appraisal Contents 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 The Conservation Area Appraisal 7 3.0 Conclusions and Recommendations 35 Appendices Appendix 1: Glossary of Terms 37 Appendix 2: Sources 41 Appendix 3: Checklist for heritage assets that make a positive contribution to the conservation area 43 Appendix 4: Contacts for Further Information 47 1 Carnforth Conservation Area Appraisal List of Figures Figure 1.1: Conservation Designations 5 Figure 2.1: Character Areas 18 Figure 2.2: Figure Ground Analysis 20 Figure 2.3: Townscape Analysis 25 Figure 2.4: Listed and Positive Buildings 34 Produced for Lancaster City Council by the Architectural History Practice and IBI Taylor Young (2012) 2 Carnforth Conservation Area Appraisal 1. Introduction 1.2 Planning Policy Context The National Planning Policy Framework This report provides a Conservation Area (NPPF, 2012) requires local planning Appraisal of the Carnforth Conservation authorities to identify and assess the Area. Following English Heritage significance of heritage assets (including guidance (Understanding Place, 2011), it Conservation Areas). It requires that describes the special character of the information about the significance of the area, assesses its current condition and historic environment should be made makes recommendations for future publicly accessible. This Appraisal directly conservation management, including for responds to these requirements. the public realm. The appraisal will also be used to inform future planning The Lancaster Core Strategy was decisions, to help protect the heritage adopted by Lancaster City Council in significance of the area. 2008. Within this document, the vision for Carnforth is "a successful market town The first draft of this appraisal formed the and service centre for North Lancashire subject of a six-week public consultation and South Cumbria". -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

How Should We Plan for Our District's Future?

Local Plan Consulatation 2015 Plan Consulatation Local People, Homes & Jobs How should we plan for our district’s future? Developing a Local Plan for Lancaster District 2011–2031 Public consultation: Monday 19 October to 30 November 2015 People, Homes and Jobs – How can we meet our future development needs? To support the needs of a growing and changing community The overall strategy to meet these needs and provide opportunities for economic growth, Lancaster City Council must prepare a local plan. A lot of development is to continue with an urban-focussed activity is already happening locally. However, there is a approach to development that is great potential to create more jobs and successful businesses through continued growth at Lancaster University, investment supplemented with additional new large in the energy sector and opportunities created by completion strategic development sites that can be of the Heysham to M6 link road. developed for housing and employment. The latest evidence on the potential for new jobs and the housing needed to provide for a growing community suggests In 2014, the council consulted on five options for new a need to plan for around 9,500 jobs and 13,000-14,000 new strategic development sites. Following the consideration of homes for the years up to 2031. these options the council is proposing a hybrid approach with The evidence also suggests that the economic sustainability a number of additional strategic sites as the district’s needs of this area could become vulnerable due to falling numbers cannot be met by one single option. This approach has been in the working age population as older workers retire and they developed based on your views from the consultation last are not being replaced by enough new workers. -

Arnside and Silverdale Milnthorpe Hollins 3 Deer Well Park Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Dallam Tower Sandside Quarry Kent Channel 2 Sandside

Arnside and Silverdale Milnthorpe Hollins 3 Deer Well Park Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Dallam Tower Sandside Quarry Kent Channel 2 Sandside Beetham Storth Fiery House Underlaid Teddy Wood Heights Beetham Fairy Steps Hall 7 Farm Hazelslack Tower Carr Bank Slackhead Beetham Fell Beetham Park Wood Edge 1 Arnside Moss 110m Ashmeadow Coastguard Lookout Arnside Major Marble Leighton Beck Woods Quarry Hale Fell Beachwood New Dobshall Barns Grubbins Wood Red Bay Wood Hills Leighton Wood Coldwell Furnace Parrock Bridge Hale Moss Blackstone Copridding Silverdale Moss Point Wood Arnside Knott 11 Nature Reserve 159m Brackenthwaite White Creek Gait Barrows National Nature Reserve Heathwaite Arnside Arnside Tower Point Little Hawes White Moss Water Thrang End Hawes Water Middlebarrow Yealand Plain Eaves Hawes Water Storrs Far Arnside Wood Moss Jubilee Mon 6 10 Pepperpot Trowbarrow 12 8 Local Nature Reserve Round Yealand Silverdale To p Redmayne The Cove Bank House Hogg Bank Well Leighton Moss Farm Wood RSPB Cringlebarrow Wood Bottoms Burton Well 5 Wood Deepdale Pond The Lots The Green Leighton Moss RSPB Know Hill Fleagarth Woodwell Know End Wood Point Summerhouse Hill 4 Heald Brow Gibraltar 9 Tower Yealand Jack Scout Crag Foot Conyers Chimney Hyning Scout Jenny Brown’s Wood Jenny Brown’s Cottages Point Barrow Scout Three RSPB Brothers Shore Hides RSPB Strickland Wood Potts Wood N Bride’s Chair Warton Crag 125m Warton Crag Disclaimer: The representation on this map of Local Nature Reserve any other road, track or path is no evidence of Morecambe Bay a right of way. Map accuracy reflects current by Absolute. 2k by the Arnside and Silverdale April 2007.