Plants, Place Names and Habitats E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pages Farm House Oxfordshire Pages Farm House Oxfordshire

PAGES FARM HOUSE OXFORDSHIRE PAGES FARM HOUSE OXFORDSHIRE A charming secluded Oxfordshire farmhouse set within a cobbled courtyard in an idyllic and private valley with no through traffic and within 1.5 miles of livery yard. Reception hall • Drawing room • Sitting room • Family room • Dining room Kitchen (with Aga)/breakfast room • Walk-in larder • Utility room • Cellar Ground floor guest bedroom and shower room • Wooden and tiled floors. Master bedroom with en suite bathroom • 1 Bedroom with dressing room and bathroom 3 Further bedrooms with family bathroom Staff/guest flat with: Living room • Kitchen • 2 Bedrooms both with en-suite bathrooms Separate studio Barn Guest cottage/Home office with: Large reception room • Shower room • 2 Attic rooms Gardens and grounds with fine views from the southfacing terrace over adjoining farmland • Vegetable garden • Duck pond orchard In all about 1.1 acres (with room for tennis court and swimming pool) Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP 20 Thameside 55 Baker Street Henley-on-Thames London Oxfordshire RG9 2LJ W1U 8AN +44 1491 844 900 +44 20 7629 8171 [email protected] [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation (All distances and times are approximate) • Henley-on-Thames – 5 miles • Oxford – 24 miles • Central London – 40 miles • Heathrow – 30 miles • M40 (J5) – 11 miles • M4 (J8/9) – 14 miles • Henley-on-Thames Station – 5 miles (London Paddington from 45 mins) • High Wycombe Station – 18 miles (London Marylebone 30 mins) • Rupert House School – Henley • Shiplake College • Queen Anne’s – Caversham • The Dragon School • Radley College • Wycombe Abbey • The Royal Grammar School – High Wycombe • Sir William Borlaise School – Marlow • Henley Golf Club • Badgemore Park • Huntercombe Golf Club Cellar Barn Ground Floor Barn First Floor First Floor Approximate Gross Internal Floor Area House - 591.9 sq.mts. -

Roakham Bottom Roke OX10 Contemporary Home in Sought After Village with Wonderful Country Views

Roakham Bottom Roke OX10 Contemporary home in sought after village with wonderful country views. A superb detached house remodelled and extended to create a very generous fi ve bedroom home. The accommodation mo notably features a acious entrance hall, modern kitchen, large si ing room with a wood burning ove and Warborough 1.8 miles, Wallingford doors out to the garden. The unning ma er bedroom has a 5 miles, Abingdon 11 miles, Didcot pi ure window to enjoy views of the garden and surrounding Parkway 11 miles (trains to London countryside. There is a utility room which benefi ts from doors to the front and rear. Paddington in 40 minutes)Thame 13 miles, Henley-On-Thames 13 miles, The house sits on a plot of approximately one third of an acre, Oxford 13 miles, Haddenham and which has been well planted to create a beautiful and very Thame Parkway 14 miles (Trains to private garden. There are many paved areas to use depending London Marylebone in 35 minutes) on the time of day. London 48 miles . (all times and Set well back from the lane the house is approached by a distances are approximate). gravel driveway o ering parking for several cars. There is also Local Authority: South Oxfordshire a car port for two cars which could be made into a garage with Di ri Council - 01235 422422 the addition of doors. There is a large workshop and in the rear garden a large summerhouse/ udio, currently used as a games room but could be converted into a home o ce. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

Where to See Red Kites in the Chilterns AREA of OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY

For further information on the 8 best locations 1 RED l Watlington Hill (Oxfordshire) KITES The Red Kite - Tel: 01494 528 051 (National Trust) i Web: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/regions/thameschilterns in the l2 Cowleaze Wood (Oxfordshire) Where to Chilterns i Tel: 01296 625 825 (Forest Enterprise) Red kites are magnificent birds of prey with a distinctive l3 Stokenchurch (Buckinghamshire) forked tail, russet plumage and a five to six foot wing span. i Tel: 01494 485 129 (Parish Council Office limited hours) see Red Kites l4 Aston Rowant National Nature Reserve (Oxfordshire) i Tel: 01844 351 833 (English Nature Reserve Office) in the Chilterns l5 Chinnor (Oxfordshire) 60 - 65cm Russet body, grey / white head, red wings i Tel: 01844 351 443 (Mike Turton Chinnor Hill Nature Reserve) with white patches on underside, tail Tel: 01844 353 267 (Parish Council Clerk mornings only) reddish above and grey / white below, 6 West Wycombe Hill (Buckinghamshire) tipped with black and deeply forked. l i Tel: 01494 528 051 (National Trust) Seen flying over open country, above Web: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/regions/thameschilterns woods and over towns and villages. 7 The Bradenham Estate (Buckinghamshire) m l c Tel: 01494 528 051 (National Trust) 5 9 Nests in tall trees within woods, i 1 Web: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/regions/thameschilterns - sometimes on top of squirrel’s dreys or 5 8 The Warburg Reserve (Oxfordshire) 7 using old crow's nests. l 1 i Tel: 01491 642001 (BBOWT Reserve Office) Scavenges mainly on dead animals Email:[email protected] (carrion), but also takes insects, Web: www.wildlifetrust.org.uk/berksbucksoxon earthworms, young birds, such as crows, weight 0.7 - 1 kg and small mammals. -

Situation of Polling Stations Police and Crime Commissioner Election

Police and Crime Commissioner Election Situation of polling stations Police area name: Thames Valley Voting area name: South Oxfordshire No. of polling Situation of polling station Description of persons entitled station to vote S1 Benson Youth Hall, Oxford Road, Benson LAA-1, LAA-1647/1 S2 Benson Youth Hall, Oxford Road, Benson LAA-7, LAA-3320 S3 Crowmarsh Gifford Village Hall, 6 Benson Lane, LAB1-1, LAB1-1020 Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford S4 North Stoke Village Hall, The Street, North LAB2-1, LAB2-314 Stoke S5 Ewelme Watercress Centre, The Street, LAC-1, LAC-710 Ewelme, Wallingford S6 St Laurence Hall, Thame Road, Warborough, LAD-1, LAD-772 Wallingford S7 Berinsfield Church Hall, Wimblestraw Road, LBA-1, LBA-1958 Berinsfield S8 Dorchester Village Hall, 7 Queen Street, LBB-1, LBB-844 Dorchester, Oxon S9 Drayton St Leonard Village Hall, Ford Lane, LBC-1, LBC-219 Drayton St Leonard S10 Berrick and Roke Village Hall, Cow Pool, LCA-1, LCA-272 Berrick Salome S10A Berrick and Roke Village Hall, Cow Pool, LCD-1, LCD-86 Berrick Salome S11 Brightwell Baldwin Village Hall, Brightwell LCB-1, LCB-159 Baldwin, Watlington, Oxon S12 Chalgrove Village Hall, Baronshurst Drive, LCC-1, LCC-1081 Chalgrove, Oxford S13 Chalgrove Village Hall, Baronshurst Drive, LCC-1082, LCC-2208 Chalgrove, Oxford S14 Kingston Blount Village Hall, Bakers Piece, LDA-1 to LDA-671 Kingston Blount S14 Kingston Blount Village Hall, Bakers Piece, LDC-1 to LDC-98 Kingston Blount S15 Chinnor Village Hall, Chinnor, Church Road, LDB-1971 to LDB-3826 Chinnor S16 Chinnor Village Hall, -

Roakham Bottom Roke | Oxfordshire | OX10 6LD

Roakham Bottom Roke | Oxfordshire | OX10 6LD Roakham Bottom Cover.indd 3 05/11/2019 09:17 ROAKHAM BOTTOM A well presented - substantial detached home. An ideal purchase for a relocating family seeking a beautiful location, with quality schooling and a whole host of leisure and recreational facilities close-by. Roakham Bottom Cover.indd 4 05/11/2019 09:17 Roakham Bottom was built around 1963 and over the years has benefitted from extensions and alterations, the most significant being in 2015, where a garage and a workshop were added with two rooms at first floor level. Double glazing to the front of the property was installed around 2014. The overall living accommodation extends to over 2,600 sq. ft. The property encompasses the very best in country-living blending all the benefits of a rural location with a host of amenities, facilities and market towns close by, with rail and road links offering connections to Oxford and London. The property provides a feeling of space and light and there are views to both the front and rear aspects. The property is equally suited for both a summer and winter life-styles, with large patio areas (ideal for outside dining ) for the summer and a sitting room with a feature wood burner for the winter. Internally the property is both stylish and contemporary with a pleasing flow from one room to another. Roakham Bottom Pages.indd 1 05/11/2019 09:19 The spacious and bright entrance hall with high vaulted ceiling, has two full height windows and a side window. -

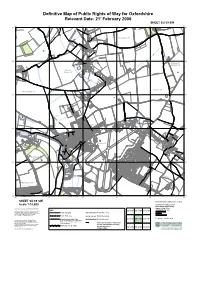

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 69 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 69 SW 307/9a 60 392/15b 61 62 63 64 65 307/9b 4200 7800 0006 0004 0003 2400 6900 6100 307/9a 95 Chy 95 0 Lonesome Farm Whitehouse Farm A 329 A 307/15 39 Kennels 2/15b 307/1 Whitehouse Lodge 2191 307/9b Drain 307/8 Ponds 204/32 8785 307/15 0082 1380 140/3 140/3 Pond Drain 307/10 204/33 204/13 Pond 5375 Drain 0075 9673 Drain Pond 9272 A 329 1972 127/9 Newington CP Pond Manor Farm Spring Spring 307/9a Pond 127/9Issues 0057 Pond RUMBOLDS LANE (Track) Myrtle Cottage Collects 6954 6454 127/8 Drain 6751 Drain 5652 Pond 307/9b Northfield Drain Mokes Corner En-dah-win Stonewold 127/7 204/33 Pond Priory The Chase Cottage Dunelm 0944 Drain Meadowcroft 0042 127/4 The Innocents Deane's Hurst 0041 Barosan Drain 204/33 Rosslyn Pond The Orchard 3535 Pond 127/7 Pond Drain 9235 127/4 Warburton Church Cottage Pond Tanner PO Cottage 3430 PH The Chequers Ivyhouse Farm Drain Drain 3728 Inn Drain Pond Pond Upper Berrick St Helen's Church 127/5 Drain 127/4 1522 0022 The Malt House 127/6 392/15b Pond Drain 1614 127/6 Pond The Old Post Office Drain Trecorn House Ponds Drain Issues Shambles 127/4 Drain 392/15a Two Jays 0001 Hollantide Cottage 0005 1500 0001 3600 3600 5600 1500 3500 204/13 0005 Berrick House 0042 0001 94 Caer Urfa 94 Parsonage Farm Lower Berrick Farm 127/5 Parsonage Cottage BERRICK Drain Stonehaven Drain Brightwell Stable 0090 Cottage SALOME Drain Cases Co Grace's Farm urt Allnuts Pond Nurseries Baldwin CP Brookfield Drain Triad Lothlorien Pond -

Traffic Sensitive Streets – Briefing Sheet

Traffic Sensitive Streets – Briefing Sheet Introduction Oxfordshire County Council has a legal duty to coordinate road works across the county, including those undertaken by utility companies. As part of this duty we can designate certain streets as ‘traffic-sensitive’, which means on these roads we can better regulate the flow of traffic by managing when works happen. For example, no road works in the centre of Henley-on-Thames during the Regatta. Sensitive streets designation is not aimed at prohibiting or limiting options for necessary road works to be undertaken. Instead it is designed to open-up necessary discussions with relevant parties to decide when would be the best time to carry out works. Criteria For a street to be considered as traffic sensitive it must meet at least one of the following criteria as set out in the table below: Traffic sensitive street criteria A The street is one on which at any time, the county council estimates traffic flow to be greater than 500 vehicles per hour per lane of carriageway, excluding bus or cycle lanes B The street is a single carriageway two-way road, the carriageway of which is less than 6.5 metres wide, having a total traffic flow of not less than 600 vehicles per hour C The street falls within a congestion charges area D Traffic flow contains more than 25% heavy commercial vehicles E The street carries in both directions more than eight buses per hour F The street is designated for pre-salting by the county council as part of its programme of winter maintenance G The street is within 100 metres of a critical signalised junction, gyratory or roundabout system H The street, or that part of a street, has a pedestrian flow rate at any time of at least 1300 persons per hour per metre width of footway I The street is on a tourist route or within an area where international, national, or significant major local events take place. -

Milestones & Waymarkers Volume

MILESTONES & WAYMARKERS THE JOURNAL OF THE MILESTONE SOCIETY VOLUME ONE 2004 ISSN 1479-5167 Editorial Panel Carol Haines Terry Keegan Tim Stevens David Viner Printed for the Society 2004 MILESTONES & WAYMARKERS The Journal of The Milestone Society This Journal is the permanent record of the work of the Society, its members and other supporters and specialists, working within its key Aim as set out below. © All material published in this volume is the copyright of the authors and of the Milestone Society. All rights reserved - no material may be reproduced without written permission. Submissions of material are welcomed and should be sent in the first instance to the Hon Secretary, Terry Keegan: The Oxleys, Clows Top, Kidderminster, Worcs DY14 9HE telephone: 01299 832358 - e-mail: [email protected] THE MILESTONE SOCIETY AIM • To identify, record, research, conserve, and interpret for public benefit the milestones and other waymarkers of the British Isles. OBJECTIVES • To publicise and promote public awareness of milestones and other waymarkers and the need for identification, recording, research and conservation, for the general benefit and education of the community at large • To enhance public awareness and enjoyment of milestones and other waymarkers and to inform and inspire the community at large of their distinctive contribution to both the local scene and to the historic landscape in general • To represent the historical significance and national importance of milestones and waymarkers in appropriate forums and through relevant -

Warburg Nature Reserve, Nettlebed

point your feet on a new path Warburg Nature Reserve, Nettlebed Distance: 8½ km=5½ miles easy-to-moderate walking Region: Chilterns Date written: 27-jul-2019 Author: Phegophilos Last update: 10-jul-2020 Refreshments: Nettlebed, Middle Assendon (after the walk) Map: 171 (Chiltern Hills South) but the maps in this guide should be sufficient Problems, changes? We depend on your feedback: [email protected] Public rights are restricted to printing, copying or distributing this document exactly as seen here, complete and without any cutting or editing. See Principles on main webpage. Nature reserve, woodland, historic village, hills, views In Brief This walk leads you from the dense microclimate of a nature reserve, into extensive woods, to the historic village of Nettlebed, then through forest and meadows on a pleasant trek ending back at the nature reserve. Refreshments are to be had in the village of Nettebed, either in the pub / hotel * or in the Field Kitchen which has produced some favourable comments. (* To enquire at the White Hart , ring 01491-641245.) This walk is also part of the Bix-Ewelme chain walk and can be combined with one or two other nearby walks to make a larger walk of up to 25 km=15½ miles. Look for the “chain link” icons in the margins or the “chain link” symbols in the map. There are a few small patches of nettles near the start of the walk, so shorts might be a problem. Underfoot the ground is fairly firm, so any strong com- fortable footwear should be fine. This walk should be ideal for your dog. -

THE PARISH of BERRICK SALOME Minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting Held on 7Th May 2009 at the Berrick Salome Village Hall at 8.00 P.M

THE PARISH OF BERRICK SALOME Minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting held on 7th May 2009 at the Berrick Salome Village Hall at 8.00 p.m. 1. Apologies for absence Nicol Glyn, David Pelling, Pam Marsh and Ruth Coffey. 2. Minutes of the last meeting The minutes of the last Annual Parish Meeting held on 1st May 2007 and the Extraordinary Parish Meeting held on 29th May 2007 were read by John Radice. Dennis Hall proposed approval, seconded by Brian Bull; and the minutes were signed by Derek Shaw. 3. Matters arising from the Minutes Jean Gladstone raised the matter of sewage tankers using the Rokemarsh lane while the pumping station was out of action – up to 18 a day, causing damage to the lane. Derek Shaw said he would be reporting on his contacts with Thames Water, and asked others to keep him informed of their contacts with TW and any responses received. 4. The Annual Report of Parish Council This was presented by the chairman, Derek Shaw: Unlike the last year 2008/2009 has been quite a busy year during which The Parish Council had 6 meetings in the Village Hall. Planning Activities As usual, most of our activities centred around planning applications of which there were 9 this year, most of which were non-controversial. Of these, 6 were approved by SODC, 1 refused and 2 are ongoing. The application which generated much discussion was that for a pair of semi-detached “affordable” houses on the site at the side of Parsonage Farm. The Parish Council, having previously opposed many applications for “large” developments, felt that whereas this site was far from idea it was difficult to oppose a request for 2 “affordable” houses. -

SODC LP2033 2ND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT FINAL.Indd

South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT Appendix 5 Safeguarding Maps 209 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 210 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 211 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 212 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 213 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 214 216 Local Plan2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONSDOCUMENT South Oxfordshire DistrictCouncil South Oxfordshire South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 216 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 217 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 218 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 219 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 220 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS