Accidents Summer Fall 2020 Appalachia Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hike Leader Handbook

Excursions Committee New Hampshire Chapter Of the Appalachian Mountain Club Hike Leader Handbook February, 2016 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 2 of 75. 2AMC–NH Chapter Excursions Committee Hike Leader Handbook Table of Contents Letter to New Graduates The Trail to Leadership – Part D Part 1 - Leader Requirements Part 2 – Hike Leader Bill of Rights Part 2a-Leader-Participant Communication Part 3 - Guidelines for Hike Leaders Part 4 - Hike Submission Procedures Part 5 – On-line Hike Entry Instructions (AMC Database) Part 5a – Meetup Posting Instructions Part 6 – Accident & Summary of Use Report Overview Part 7 - AMC Incident Report Form Part 8 - WMNF Use Report Form Part 9 - Excursions Committee Meetings Part 10 - Mentor Program Overview Part 11 – Leader Candidate Requirements Part 12 - Mentor Requirements Part 13 - Mentor Evaluation Form Part 14 - Class 1 & 2 Peaks List Part 15 - Class 3 Peaks List Part 16 - Liability Release Form Instructions Part 17 - Release Form FAQs Part 18 - Release Form Part 19 - Activity Finance Policy Part 20 - Yahoo Group Part 21 – Leadership Recognition Part 22 – Crosswalk between Classes and Committees NH AMC Excursion Committee Bylaws Page 1 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 3 of 75. Page 2 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 4 of 75. Hello, Leadership Class Graduate! We hope that you enjoyed yourself at the workshop, and found the weekend worthwhile. We also hope that you will consider becoming a NH Chapter AMC Hike leader—you’ll be a welcome addition to our roster of leaders, and will have a fun and rewarding experience to boot! About the Excursions Committee: We are the hikers in the New Hampshire Chapter, and we also lead some cycling hikes. -

A Line of Scouts: Personal History from Mead Base Camp in Center Sandwich, New Hampshire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Dartmouth Digital Commons (Dartmouth College) Appalachia Volume 71 Number 1 Winter/Spring 2020: Farewell, Mary Article 40 Oliver: Tributes and Stories 2020 A Line of Scouts: Personal History from Mead Base Camp in Center Sandwich, New Hampshire William Geller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Geller, William (2020) "A Line of Scouts: Personal History from Mead Base Camp in Center Sandwich, New Hampshire," Appalachia: Vol. 71 : No. 1 , Article 40. Available at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia/vol71/iss1/40 This In This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Appalachia by an authorized editor of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Line of Scouts Personal history from Mead Base Camp in Center Sandwich, New Hampshire William Geller 84 Appalachia Appalachia_WS2020_FINAL 10.28.19_REV.indd 84 10/28/19 1:39 PM oin me on A weeklong group backpacking trip in August 1966. J I was a 19-year-old leader of a group of 53, mostly Boy Scouts and a few leaders. We would walk through New Hampshire’s Sandwich Notch, cross over Sandwich Dome, pass through Waterville Valley and Greeley Ponds, into the depths of the Pemigewasset Wilderness. Next we would climb the Hancocks on a side trip then traverse the Bonds to Zeacliff Trail and Zealand Falls, down into Crawford Notch, and up Crawford Path to Mount Washington. -

Charles Rivermud

TRIP LISTINGS: 3 - 11 RUMBLINGS: 2, ARTICLE: 1 CharlesTHE River Mud APPALACHIAN MOUNTAIN CLUB / BOSTON CHAPTER :: www.amcboston.org August 2010 / Vol. 35, No. 8 ARTICLE By Fruzsina Veress Accidents Happen: A Hiker Offers Thanks to Her Rescuers Watch out for the Leg! Lift the Leg! Pull the Leg to the right! the hut and ask for help. Indeed, we were happy when they The Leg was MY leg, hanging uselessly in its thick bandage called later to say that they had met the two valiant caretak- made from a foam mattress. Suspended by a rope, the Leg ers from Madison Hut on their way to reach us. After about was being handled by one of my heroic rescuers while its two hours of anxious waiting spent mostly hunting down rightful owner crept along behind on her remaining three mosquitoes, the two kind AMC-ers arrived. They splinted limbs (and butt) like a crab led on a leash. The scenery was my ankle, and to protect it from bumping into the boulders, beautiful, the rocky drops of King Ravine. they packaged it into the foam mattress. Earlier on this day, June 28, Nandi and Marton were pre- climbing happily over the pared to piggyback me down boulder field, hoping to reach the ravine, but most of the the ridge leading to Mount ‘trail’ simply consists of blaz- Adams in the White Moun- es painted on the rock, and it tains of New Hampshire, I is next to impossible for two took a wrong step. There was or more people to coordinate a pop, and suddenly my foot their steps. -

Senior Camp Behavior Contract

2020 Senior Camp Family Handbook Dear Senior Camp Parents, We are thrilled that your child is joining us again this summer and are confident that this will be another outstanding summer for our community. Senior Camp provides unique opportunities for our campers to stretch themselves far beyond their comfort zone. From our years of experience, we know that those who push and challenge themselves in Senior Camp have the most rewarding summers of their camp experience. This is not easy for young people who are still figuring out who they are. We hope you will take the opportunity to encourage your child to participate in a bike trip, a 3-5 day hiking and camping trip (“traverse” in CWW lingo), try out for the play, participate in intercamp competitions, engage in volunteer work when possible, and fully throw themselves into the camp schedule. Like so many things in life, your teen will get out of the Senior Camp experience what they put into it and your support in this leading up to camp and throughout the summer is paramount. We recognize that learning to navigate these early teen years can be challenging in a variety of ways and is unique to every family. As in all of your prior years at CWW, we know your teen will be most successful when we work together to understand both the young person that arrives to us in June and the young person that learns, grows and changes over the course of the summer to return to your home. These years are not always easy and we will strive to empower your child through unique program opportunities and social situations to better understand who they are and help them reach their full potential. -

Fall 2009 Vol. 28 No. 3

V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Fall 2009 Vol. 28, No. 3 V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 3 Fall 2009 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Western Kingbird by Leonard Medlock, 11/17/09, at the Rochester wastewater treatment plant, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. New Hampshire Bird Records © NHA April, 2010 www.nhbirdrecords.org Published by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department Printed on Recycled Paper V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page 1 IN MEMORY OF Tudor Richards We continue to honor Tudor Richards with this third of the four 2009 New Hampshire Bird Records issues in his memory. -

SEARS of NORTH CONWAYSEARS DEALER ROP JA#803C004 Sears Price Match Plus Policy

VOLUME 32, NUMBER 46 MARCH 27, 2008 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Case In Point: Conway Library’s Head Librarian is quiet and oh so capable … A 2 Mountain Wheels: The Snowcoach is the latest in a long line of vehicles to travel the Auto Road … A 6 Conway Chamber Concert: The Meliora String Quartet to perform at Salyard’s Center … B1 Jazzing It Up: If you like jazz, don’t miss the Fryeburg Academy Jazz Jackson, NH 03846 • Lodging: 383-9443 • Recreation: 383-0845 Ensemble concerts … www.nestlenookfarm.com • 1-877-445-2022 B2 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH SSTTOORRYY LLAANNDD Case In Point CC OO RR NN EE RR If you build it they will come Margaret Marschner: a pillar in growth of Conway Library NEW THIS By PG Case But that proved to be not enough. The building’s square footage dou- THE CONWAY LIBRARY IS A “As the population grew, so did the need bled again to 16,000 with the new addi- SUMMER: gem. It is a clean, well lighted place, and we had to start looking at ways to tion, but Marschner says she can’t imag- uncrowded and tastefully appointed. increase the space again,” Marschner ine having to add on again during her The entrance to the turn of the last cen- says. “We started working with archi- tenure. The staff, too, has grown, but Join the Circus for tury structure sort of sweeps up to the tects about 10 years before the new addi- without having to add too many new doors and the inside is handsome, well tion would finally get built. -

Pre-European Colonization 1771 1809 1819 1826 1840 July 23, 1851

MOVED BY MOUNTAINS In this woodblock by In the first big wave of trail building, The Abenaki Presence Endures Marshall Field, Ethan Hiker-Built Trails Deepen Pride of Place Allen Crawford is depicted hotel owners financed the construction carrying a bear, one of the of bridle paths to fill hotel beds and cater For millennia, Abenaki people traveled on foot and by canoe many legends that gave the By the late 19th century, trails throughout the region for hunting, trading, diplomacy and White Mountains an allure to a growing leisure class infatuated by were being built by walkers for that attracted luminaries, “the sublime” in paintings and writings. war. The main routes followed river corridors, as shown such as Daniel Webster, walkers in the most spectacular in this 1958 map by historian and archaeologist Chester Henry David Thoreau and This inset is from a larger 1859 map and Nathaniel Hawthorne. settings. Hiking clubs developed Price. By the late 1700s, colonialism, disease, warfare and drawing by Franklin Leavitt. distinct identities, local loyalties European settlement had decimated native communities. GLADYS BROOKS MEMORIAL LIBRARY, MOUNT WASHINGTON OBSERVATORY and enduring legacies. Their main foot trails were taken over and later supplanted by stagecoach roads, railroads and eventually state highways. DARTMOUTH DIGITAL LIBRARY COLLECTIONS “As I was standing on an Grand Hotels Build Trails for Profit old log chopping, with my WONALANCET OUT DOOR CLUB Native footpaths axe raised, the log broke, The actual experience of riding horseback on a For example, the Wonalancet Out Door Club developed its identity were often faint and I came down with bridle path was quite a bit rougher than suggested around its trademark blue sign posts, its land conservation advocacy to modern eyes by this 1868 painting by Winslow Homer. -

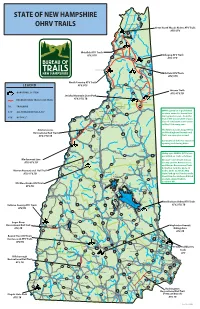

State of New Hampshire Ohrv Trails

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Third Connecticut Lake 3 OHRV TRAILS Second Connecticut Lake First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods Riders ATV Trails ATV, UTV 3 Pittsburg Lake Francis 145 Metallak ATV Trails Colebrook ATV, UTV Dixville Notch Umbagog ATV Trails 3 ATV, UTV 26 16 ErrolLake Umbagog N. Stratford 26 Millsfield ATV Trails 16 ATV, UTV North Country ATV Trails LEGEND ATV, UTV Stark 110 Groveton Milan Success Trails OHRV TRAIL SYSTEM 110 ATV, UTV, TB Jericho Mountain State Park ATV, UTV, TB RECREATIONAL TRAIL / LINK TRAIL Lancaster Berlin TB: TRAILBIKE 3 Jefferson 16 302 Gorham 116 OHRV operation is prohibited ATV: ALL TERRAIN VEHICLE, 50” 135 Whitefield on state-owned or leased land 2 115 during mud season - from the UTV: UP TO 62” Littleton end of the snowmobile season 135 Carroll Bethleham (loss of consistent snow cover) Mt. Washington Bretton Woods to May 23rd every year. 93 Twin Mountain Franconia 3 Ammonoosuc The Ammonoosuc, Sugar River, Recreational Rail Trail 302 16 and Rockingham Recreational 10 302 116 Jackson Trails are open year-round. ATV, UTV, TB Woodsville Franconia Crawford Notch Notch Contact local clubs for seasonal opening and closing dates. Bartlett 112 North Haverhill Lincoln North Woodstock Conway Utility style OHRV’s (UTV’s) are 10 112 302 permitted on trails as follows: 118 Conway Waterville Valley Blackmount Line On state-owned trails in Coos 16 ATV, UTV, TB Warren County and the Ammonoosuc 49 Eaton Orford Madison and Warren Recreational Trails in Grafton Counties up to 62 Wentworth Tamworth Warren Recreational Rail Trail 153 inches wide. In Jericho Mtn Campton ATV, UTV, TB State Park up to 65 inches wide. -

Download It FREE Today! the SKI LIFE

SKI WEEKEND CLASSIC CANNON November 2017 From Sugarbush to peaks across New England, skiers and riders are ready to rock WELCOME TO SNOWTOPIA A experience has arrived in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. grand new LINCOLN, NH | RIVERWALKRESORTATLOON.COM Arriving is your escape. Access snow, terrain and hospitality – as reliable as you’ve heard and as convenient as you deserve. SLOPESIDE THIS IS YOUR DESTINATION. SKI & STAY Kids Eat Free $ * from 119 pp/pn with Full Breakfast for Two EXIT LoonMtn.com/Stay HERE Featuring indoor pool, health club & spa, Loon Mountain Resort slopeside hot tub, two restaurants and more! * Quad occupancy with a minimum two-night Exit 32 off I-93 | Lincoln, NH stay. Plus tax & resort fee. One child (12 & under) eats free with each paying adult. May not be combined with any other offer or discount. Early- Save on Lift Tickets only at and late-season specials available. LoonMtn.com/Tickets A grand new experience has arrived in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Arriving is your escape. Access snow, terrain and hospitality – as reliable as you’ve heard and as convenient as you deserve. SLOPESIDE THIS IS YOUR DESTINATION. SKI & STAY Kids Eat Free $ * from 119 pp/pn with Full Breakfast for Two EXIT LoonMtn.com/Stay HERE Featuring indoor pool, health club & spa, Loon Mountain Resort slopeside hot tub, two restaurants and more! We believe that every vacation should be truly extraordinary. Our goal Exit 32 off I-93 | Lincoln, NH * Quad occupancy with a minimum two-night stay. Plus tax & resort fee. One child (12 & under) is to provide an unparalleled level of service in a spectacular mountain setting. -

Appendix B: Habitats

Appendix B: Habitats Alpine Photo by Ben Kimball Acres in NH: 4158 Percent of NH Area: <1 Acres Protected: 4158 Percent Protected: 100 Habitat Distribution Map Habitat Description In New Hampshire, alpine habitat occurs above treeline (trees taller than 6 ft.) at approximately 4,900 ft., primarily within the Franconia and Presidential Ranges of the White Mountains. This region endures high winds, precipitation, cloud cover, and fog, resulting in low annual temperatures and a short growing season (Bliss 1963, Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). The interaction between severe climate and geologic features—such as bedrock, exposure, and aspect—determine the distribution and structure of alpine systems (Antevs 1932, Bliss 1963, Harries 1966, Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). Alpine habitat is comprised of low, treeless tundra communities embedded in a matrix of bedrock, stone, talus, or gravel, with or without thin organic soil layers, and interspersed with krummholz. Soils are well drained, highly acidic, nutrient poor, and weakly developed (Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). Alpine vegetation is grouped into four natural community systems by NHNHB (Sperduto 2011): the alpine tundra, alpine ravine/snowbank, subalpine heath ‐ krummholz/rocky bald, and alpine/subalpine bog systems. The alpine tundra is the primary system in the alpine zone, and occupies most of the summits, ridges, and slopes above treeline. The system is named for its resemblance to the tundra of the arctic zone, and is dominated by mat‐forming shrubs like diapensia (Diapensia lapponica), alpine blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), bearberry willow (Salix uvaursi), and alpine‐azalea (Kalmia procumbens), and graminoids such as Bigelow's sedge (Carex bigelowii) and highland rush (Juncus trifidus). -

White Mountain National F Orest

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Eastern Region May, 2005 Environmental Assessment for the Warren to Woodstock Snowmobile Trail Project For addition information, contact Susan Mathison Ammonoosuc-Pemigewasset Ranger District White Mountain National Forest 1171 Route 175 Holderness, NH 03265 Phone: 603-536-1315 (voice); 603-528-8722 (TTY) Fax: 603-536-5147 E-mail: [email protected]. White Mountain National Forest White Mountain National Forest Environmental Assessment Table of Contents Chapter 1: Purpose and Need................................................. 4 What is the Forest Service Proposing? .............................................................................................. 4 Where is the Warren to Woodstock Snowmobile Trail Project? ............................................. 4 Background .......................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose & Need ............................................................................................................................ 10 Why is the Forest Service proposing activities in the Warren to Woodstock Snowmobile Trail Project Area? ..................................................................................................................... 10 What is the site-specific need identified for the Warren to Woodstock Snowmobile Trail Project Area? ................................................................................................................................ -

North Conway, NH, a Profes- out N About Money Matters

VOLUME 37, NUMBER 7 JULY 19, 2012 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Now offering guided photo tours Biking Kayaking Hiking Outfitters Shop Glen View Café The Healing On the Garden Links Rt. 16, Pinkham Notch www.greatglentrails.com The Ear welcomes Kathy Lambert July Champs! PAGE 30 www.mtwashingtonautoroad.com to our family of writers. PAGE 14 (603) 466-2333 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH Summer Family Outing By Darron Laughland By Darron Laughland Kids love to feed the residents of the Polar Caves Animal Park and Duck Pond. The Lemon Squeeze is the grand finale, tightening down to only fourteen inches. Polar Caves a Subterranean Adventure for the Family By Darron Laughland The trails are marked with nat- The walkways make their way As the last of the most recent ural history, human history, and partway up the cliff to a great glaciers receded fifty thousand geological items of interest. view of the Baker River Valley, years ago, after ice sheets many Throughout the park, signage framed by rolling hills and the hundreds of feet thick had identifies plant species such as Sandwich Range to the scoured the northeast, masses of ferns, trees, and even the lichens Southeast. boulders and talus piles lay at that cover the rocks. The walkways and ladders the base of some cliffs. These Humans have been using the were fine for the boys to negoti- piles of huge boulders were caves for a long time. Artifacts ate and they were able to move stacked on top of each other, from native people, early through the caves safely.