Myanmar the Institution of Torture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B U R M a B U L L E T

B U R M A B U L L E T I N ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞A month-in-review of events in Burma∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ A L T E R N A T I V E A S E A N N E T W O R K O N B U R M A campaigns, advocacy & capacity-building for human rights & democracy Issue 20 August 2008 • Fearing a wave of demonstrations commemorating th IN THIS ISSUE the 20 anniversary of the nationwide uprising, the SPDC embarks on a massive crackdown on political KEY STORY activists. The regime arrests 71 activists, including 1 August crackdown eight NLD members, two elected MPs, and three 2 Activists arrested Buddhist monks. 2 Prison sentences • Despite the regime’s crackdown, students, workers, 3 Monks targeted and ordinary citizens across Burma carry out INSIDE BURMA peaceful demonstrations, activities, and acts of 3 8-8-8 Demonstrations defiance against the SPDC to commemorate 8-8-88. 4 Daw Aung San Suu Kyi 4 Cyclone Nargis aid • Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is allowed to meet with her 5 Cyclone camps close lawyer for the first time in five years. She also 5 SPDC aid windfall receives a visit from her doctor. Daw Suu is rumored 5 Floods to have started a hunger strike. 5 More trucks from China • UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Burma HUMAN RIGHTS 5 Ojea Quintana goes to Burma Tomás Ojea Quintana makes his first visit to the 6 Rape of ethnic women country. The SPDC controls his meeting agenda and restricts his freedom of movement. -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25

2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Articles 60 and 301 thereof, Having regard to Common Position 2007/750/CFSP of 19 November 2007 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (1), Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Whereas: (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council, concerned at the absence of progress towards democratisation and at the continuing violation of human rights in Burma/Myanmar, imposed certain restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar by Common Position 1996/635/CFSP (2). -

A Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon

A Strategic A Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC) UrbanDevelopment Plan of Greater The Republic of the Union of Myanmar A Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon The Project for the Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Yangon FINAL REPORT I Part-I: The Current Conditions FINAL REPORT I FINAL Part - I:The Current Conditions April 2013 Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. NJS Consultants Co., Ltd. YACHIYO Engineering Co., Ltd. International Development Center of Japan Inc. Asia Air Survey Co., Ltd. 2013 April ALMEC Corporation JICA EI JR 13-132 N 0 300km 0 20km INDIA CHINA Yangon Region BANGLADESH MYANMAR LAOS Taikkyi T.S. Yangon Region Greater Yangon THAILAND Hmawbi T.S. Hlegu T.S. Htantabin T.S. Yangon City Kayan T.S. 20km 30km Twantay T.S. Thanlyin T.S. Thongwa T.S. Thilawa Port & SEZ Planning調査対象地域 Area Kyauktan T.S. Kawhmu T.S. Kungyangon T.S. 調査対象地域Greater Yangon (Yangon City and Periphery 6 Townships) ヤンゴン地域Yangon Region Planning調査対象位置図 Area ヤンゴン市Yangon City The Project for the Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Final Report I The Project for The Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Final Report I < Part-I: The Current Conditions > The Final Report I consists of three parts as shown below, and this is Part-I. 1. Part-I: The Current Conditions 2. Part-II: The Master Plan 3. Part-III: Appendix TABLE OF CONTENTS Page < Part-I: The Current Conditions > CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives .................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 Study Period ............................................................................................................. -

30 May 2021 1 30 May 21 Gnlm

MONASTIC EDUCATION SCHOOLS, RELIABLE FOR CHILDREN BOTH FROM URBAN AND RURAL AREAS PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Union Minister U Aung Naing Oo inspects Night market to be built in investment activities in Magway Region Magway PAGE-3 PAGE-3 Vol. VIII, No. 41, 5th Waning of Kason 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Sunday, 30 May 2021 Announcement of Union Election Commission 29 May 2021 1. Regarding the Multiparty General Election held on 8 November 2020, the Union Election Commission has inspected the voter lists and the casting of votes of Khamti, Homalin, Leshi, Lahe, Nanyun, Mawlaik and Phaungpyin townships of Sagaing Region. 2. According to the inspection, the previous election commission released 401,918 eligible voters in these seven townships of Sagaing Region. The list of the Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population in November 2020 showed 321,347 eligible voters who had turned 18. The voter lists mentioned that there were 51,461 citizens, associate citizens, naturalized citizens, and non-identity voters, 8,840 persons repeated on the voter lists more than three times and 48,932 persons repeated on the voter lists two times. SEE PAGE-6 Magway Region to develop new eco-tourism INSIDE TODAY NATIONAL Union Minister site near Shwesettaw area U Chitt Naing A new eco-tourism destina- meets Information tion will be developed within Ministry the Shwesettaw area in Minbu employees Township, according to the Mag- PAGE-4 way Region Directorate of Ho- tels and Tourism Department. Under the management of NATIONAL the Magway Region Administra- Yangon workers’ tion Council and with the sug- hospital reaccepts gestion of the Ministry of Hotels inpatients except for and Tourism, the project will major surgery cases be implemented on the 60-acre PAGE-4 large area on the right side of Hlay Tin bridge situated on the Minbu-Shwesettaw road. -

'Going Back to the Old Ways'

‘GOING BACK TO THE OLD WAYS’ A NEW GENERATION OF PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE IN MYANMAR On 8 November 2015 Myanmar will hold widely anticipated general elections – the first since President Thein Sein and his quasi-civilian government came to power in 2011 after almost five decades of military rule. The elections take place against a backdrop of Under pressure from the international commu- much-touted political, economic, and social re- nity, in 2012 and 2013 President Thein Sein forms, which the government hopes will signal ordered mass prisoner releases which saw to the international community that progress is hundreds of prisoners of conscience freed after being made. years – and in some cases more than a decade – behind bars. These releases prompted cautious “As the election is getting near, most of the optimism that Myanmar was moving towards people who speak out are getting arrested. greater respect for freedom of expression. In I am very concerned. Many activists… are response, the international community began to facing lots of charges. This is a situation relax the pressure, believing that the authorities the government has created – they can pick could and would finally bring about meaningful up anyone they want, when they want.” and long-lasting human rights reforms. Human rights activist from Mandalay, “They [the authorities] have enough July 2015. laws, they can charge anyone with anything. At the same time, they want Yet for many in Myanmar’s vibrant civil society, to pretend that people have rights. But the picture isn’t as rosy as it is often portrayed. as soon as you make problems for them Since the start of 2014, the authorities have or their business they will arrest you.” increasingly stifled peaceful activism and dis- sent – tactics usually associated with the former Min Ko Naing, former prisoner of conscience and military government. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006

Burma Page 1 of 24 2005 Human Rights Report Released | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Burma Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Since 1962, Burma, with an estimated population of more than 52 million, has been ruled by a succession of highly authoritarian military regimes dominated by the majority Burman ethnic group. The current controlling military regime, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, is the country's de facto government, with subordinate Peace and Development Councils ruling by decree at the division, state, city, township, ward, and village levels. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a generally free and fair parliamentary election, but the junta refused to recognize the results. Twice during the year, the SPDC convened the National Convention (NC) as part of its purported "Seven-Step Road Map to Democracy." The NC, designed to produce a new constitution, excluded the largest opposition parties and did not allow free debate. The military government totally controlled the country's armed forces, excluding a few active insurgent groups. The government's human rights record worsened during the year, and the government continued to commit numerous serious abuses. The following human rights abuses were reported: abridgement of the right to change the government extrajudicial killings, including custodial deaths disappearances rape, torture, and beatings of -

DASHED HOPES the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DASHED HOPES The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Background ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Section 66(d) -

Market Access Landscape Country Report

Vector Control in the Indo-Pacific: Market Access Landscape Country Report Myanmar INNOVATIVE VECTOR CONTROL CONSORTIUM November 2019 Contents 1. Executive Summary 04 2. Introduction 05 2.1 Country Overview 05 2.1.1 Geography 05 2.1.2 Demographics 05 2.1.2.1 Health Indicators 06 2.1.2.2 Employment 07 2.1.2.3 Living Conditions (Lifestyle) 07 2.1.2.4 Others (Internet Usage, Education, etc.) 08 2.1.3 Economic Situation 09 2.1.4 Health Status 10 2.1.4.1 Healthcare Structure 10 2.1.4.2 Healthcare Spending 11 3. Vector Control Market Overview 11 3.1 Vector Control Overview 11 3.1.1 Vector Borne Diseases (VBD) Trends 12 3.1.2 Burden of Disease 13 3.1.3 Economic Burden of VBD 15 3.1.4 Measures/Initiatives for Vector Control 15 3.1.5 Challenges 21 4. Market Analysis 22 4.1 Procurement Channels 22 4.1.1 Overview of Procurement Channels 23 4.1.2 Stakeholders 25 4.1.3 Procurement Channels – Gap Analysis 26 4.2 Sponsors & Payers 27 4.3 Vector Control related Spending 28 4.3.1 Funding 28 4.3.1.1 National Funding 29 4.3.1.2 International Funding 30 4.3.2 Funding Gap 33 4.4 Market Description and Analysis 33 4.4.1 Level and Need of Awareness of Vector Control Products 36 5. Regulatory Pathways 38 6. Market Dynamics 40 6.1 Market Trends 40 6.2 Market Drivers 41 6.3 Success Stories 42 7. Market Access Analysis 43 8. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Life Story of Shwe Oo Min Sayadaw Bhaddanta Kawthala Maha Thera

The Life Story of Shwe Oo Min Sayadaw Bhaddanta Kawthala Maha Thera Published and Distributed by Shwe Oo Min Dhamma Sukkha Yeiktha (New PadamyaMyo – Mingaladon Township) Shwe Oo Min Tawya Dhamma Yeiktha (North Okkalapa Township) The Life Story Of Shwe Oo Min Sayadaw Bhaddanta Kawthala Maha Thera Shwe Oo Min Sayadaw Bhaddanta Kawthala Maha Thera 1913 – 2002 Page 2 of 15 Dhamma Dana Maung Paw, California PREFACE This book is a translation of the original book Titled “ The Life Story of Shwe Oo Min Sayadaw Bhaddanta Kawtala Maha Thera” published in Burmese and distributed by Shwe Oo Min Tawya Dhamma Sukkha Yeiktha, and Shwe Oo Min Tawya Dhamma Yeiktha. The book is published and distributed through the Internet as Dhamma Dana in grateful respect and honor to the great Dhamma Teacher Shwe Oo Min Sayadaw who has finally attained the deathless, the path to the deathless, what he taught us – “ To be mindful all the time. and lead a Noble and Righteous Life ” This book is distributed to honor the, the great Dhamma Teacher who leads us the way to the deathless – Nibbana Verse 21. Mindfulness is the way to the Deathless (Nibbana); unmindfulness is the way to Death. Those who are mindful do not die; those who are not mindful are as if already dead. Verse 22. Fully comprehending this, the wise, who are mindful, rejoice in being mindful and find delight in the domain of the Noble Ones (Ariyas). Verse 23. The wise, constantly cultivating Tranquility and Insight Development Practice, being ever mindful and steadfastly striving, realize Nibbana: Nibbana, which is free from the bonds of yoga*; Nibbana, the Incomparable! Dhammapada Verses No. -

Urgent Action

Further information on UA: 14/16 Index: ASA 16/4371/2016 Myanmar Date: 1 July 2016 URGENT ACTION PRISONER OF CONSCIENCE U GAMBIRA RELEASED Prisoner of conscience U Gambira was released on 1 July after all charges against him were dropped by courts in Myanmar. On 1 July U Gambira, also known as Nyi Nyi Lwin, was released from Insein prison in Yangon after completing his sentence under immigration charges and after courts dropped all other charges pending against him. U Gambira was arrested on 19 January, several days after entering Myanmar from Thailand, where he had been living. As a Myanmar citizen, he had travelled to Myanmar to apply for a passport but was sentenced in April to six months in prison with hard labour for entering the country illegally. On 28 June he received additional charges in Yangon for activities dating back to 2012 when U Gambira was released after having been imprisoned since 2007 for his leading role in mass anti-government protests, known as the Saffron Revolution. Upon his release he tried to re-open monasteries which the authorities had closed down because of the activities of their monks during the Saffron Revolution. Amnesty International believed these charges to be politically motivated. U Gambira should have never been imprisoned in the first place. Amnesty International will continue to campaign for the release of all prisoners of conscience in Myanmar. Thank you to all those who sent appeals. No further action is requested from the UA network. This is the fourth update of UA 14/16. Further information: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ASA16/4339/2016/en/ Name: U Gambira Gender m/f: m Further information on UA: 14/16 Index: ASA 16/4371/2016 Issue Date: 1 July 2016 . -

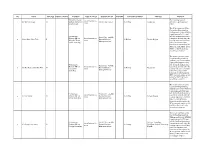

Warrant Lists English

No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Minister of Social For encouraging civil Issued warrant to 1 Dr. Win Myat Aye M Welfare, Relief and Penal Code S:505-a In Hiding Naypyitaw servants to participate in arrest Resettlement CDM The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 2 (Daw) Phyu Phyu Thin F Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region Mingalar Taung arrest coup in response to military Management law Nyunt Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 3 (U) Yee Mon (aka) U Tin Thit M Natural Disaster In Hiding Naypyitaw Potevathiri arrest coup in response to military Management law Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and self-declared parliamentary Pyihtaungsu Penal Code - 505(B), Issued warrant to committee formed after the 4 (U) Tun Myint M Hluttaw MP for Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region arrest coup in response to military Bahan Township Management law rule.