WAITING for GODOT Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beckett & Aesthetics

09/25/21 Beckett & Aesthetics | Goldsmiths, University of London Beckett & Aesthetics View Online 1. Beckett, S.: Watt. John Calder, London (1963). 2. Connor, S.: ‘Shifting Ground: Beckett and Nauman’, http://www.stevenconnor.com/beckettnauman/. 3. Tubridy, D.: ‘Beckett’s Spectral Silence: Breath and the Sublime’. 1, 102–122 (2010). 4. Lyotard, J.F., Bennington, G., Bowlby, R.: ‘After the Sublime, the State of Aesthetics’. In: The inhuman: reflections on time. Polity, Cambridge (1991). 5. Lyotard, J.-F.: The Sublime and the Avant-Garde. In: The inhuman: reflections on time. pp. 89–107. Polity, Cambridge (1991). 6. Krauss, R.: LeWitt’s Ark. October. 121, 111–113 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1162/octo.2007.121.1.111. 1/4 09/25/21 Beckett & Aesthetics | Goldsmiths, University of London 7. Simon Critchley: Who Speaks in the Work of Samuel Beckett? Yale French Studies. 114–130 (1998). 8. Kathryn Chiong: Nauman’s Beckett Walk. October. 86, 63–81 (1998). 9. Deleuze, G.: ‘He Stuttered’. In: Essays critical and clinical. pp. 107–114. Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis (1997). 10. Deleuze, G., Smith, D.W.: ‘The Greatest Irish Film (Beckett’s ‘Film’)’. In: Essays critical and clinical. pp. 23–26. Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis (1997). 11. Adorno, T.: ‘Trying to Understand Endgame’. In: Samuel Beckett. pp. 39–49. Longman, New York (1999). 12. Laws, C.: ‘Morton Feldman’s Neither: A Musical Translation of Beckett’s Text'. In: Samuel Beckett and music. pp. 57–85. Clarendon Press, Oxford (1998). 13. Cage, J.: ‘The Future of Music: Credo’. In: Audio culture: readings in modern music. pp. 25–28. -

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra Anglického Jazyka a Literatury

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury AXIOLOGICAL DYNAMICS IN SAMUEL BECKETT'S PLAYS Diplomová práce Brno 2015 Autor práce: Vedoucí práce: Bc. Monika Chmelařová Mgr. Jaroslav Izavčuk Anotace Předmětem diplomové práce Axiologické proměny v dramatickém díle Samuela Becketta je analýza Beckettových her s tematicky vyměřenou interpretací za účelem stanovení prvků v axiologické rovině. Stěžejním cílem práce je vymezení klíčových hodnot v autorově dramatické tvorbě, obsáhnutí charakteru a stimulů axiologické dynamiky. Práce je založena na kritickém zhodnocení autobiografie a vývoje hodnotové orientace Samuela Becketta na poli osobním i autorském, a to při posouzení vývoje hodnot již od počátku autorova života a tvorby. Beckettovy hry jsou výsledkem již vlastní specifické poetiky; práce si dává za cíl sledovat, co přispělo k jejímu utvoření, jaké hodnoty jsou v jeho dramatu zastoupeny a jakým způsobem se jeho dramatická tvorba axiologicky vyvíjí. Výstupem práce je kritický pohled na co nejkomplexnější autorovo dramatické dílo z pohledu hodnot a stanovení příčin těchto proměn, a to v tematicko-komparativním a diachronním (tj. chronologickém) pojetí. Abstract The subject of the diploma thesis Axiological Dynamics in Samuel Beckett's Plays is a thematically determined interpretation with the intention to determine features within the axiological level. The crucial part of the thesis is the determination of significant values in author's dramatic works, characterization of nature and stimuli of axiological dynamics. The thesis is based on critical evaluation of autobiography and development of value orientation of Samuel Beckett in private and authorial fields, i. e. with consideration of the development of values from the beginning of author's life and work. -

Here Is Endlessness Somewhere Else

Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau White Office 26, rue George Sand, 37000 Tours Vernissage : vendredi 21 mai 2010 Exposition du 22 mai au 13 juin 2010 Titre : Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else (Bas Jan Ader (“here is always somewhere else”) + Samuel Beckett (“lessness” – “sans”)) James Joyce, “Ulysse” : “le froid des espaces interstellaires, des milliers de degrés en-dessous du point de congélation ou du zéro absolu de Fahrenheit, centigrade ou Réaumur : les indices premiers de l’aube proche.” Alphaville – Jean-Luc Godard Alfaville Mel Bochner & TTrioreau (4 affiches perforées sur mur gris – édition multiples : 5 + 2 EA) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (néon blanc sur mur gris – édition multiples : 5 + 2 EA) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – façade grise + fenêtre écran, format panavision 2/35) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – intérieur gris + projecteur 35mm, film 35mm vierge gris, format panavision 2/35 + néon blanc sur mur gris) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – intérieur gris + projecteur 35mm, film 35mm vierge gris, format panavision 2/35 + néon blanc sur mur gris) Annexes : Lessness A Story by SAMUEL BECKETT (1970) Ruins true refuge long last towards which so many false time out of mind. All sides endlessness earth sky as one no sound no stir. Grey face two pale blue little body heart beating only up right. Blacked out fallen open four walls over backwards true refuge issueless. Scattered ruins same grey as the sand ash grey true refuge. Four square all light sheer white blank planes all gone from mind. Never was but grey air timeless no sound figment the passing light. -

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

Ian Watt, the Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding (Chatto & Windus 1957; Rep

Ian Watt, The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding (Chatto & Windus 1957; rep. Univ. of California Press 1957). Note: this copy has been made from a PDF version of the 1957 California UP edition. The footnotes in that editon have been transposed to endnotes here and the page-numbers have been omitted. Chapter I: Realism and the Novel Form THERE are still no wholly satisfactory answers to many of the general questions which anyone interested in the early eighteenth-century novelists and their works is likely to ask: Is the novel a new literary form? And if we assume, as is commonly done, that it is, and that it was begun by Defoe, Richardson and Fielding, how does it differ from the prose fiction of the past, from that of Greece, for example, or that of the Middle Ages, or of seventeenth-century France? And is there any reason why these differences appeared when and where they did? Such large questions are never easy to approach, much less to answer, and they are particularly difficult in this case because Defoe, Richardson and Fielding do not in the usual sense constitute a literary school. Indeed their works show so little sign of mutual influence and are so different in nature that at first sight it appears that our curiosity about the rise of the novel is unlikely to find any satisfaction other than the meagre one afforded by the terms ‘genius’ and ‘accident’, the twin faces on the Janus of the dead ends of literary history. We cannot, of course, do without them: on the other hand there is not much we can do with them. -

In Search of Enlightenment by Reading Samuel Beckett’S Waiting for Godot

LITERARIA An International Journal of New Literature Across the World ISSN: 2229-4600 VOL. 5, No. 1-2, JAN-DEC 2015 In Search of Enlightenment by Reading Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot SYED ISMYL MAHMOOD RIZVI Patna University, Patna ABSTRACT Beckett’s philosophical indebtedness has long been recognised – especially in conjunction with Dante, Descartes and Geulincx. In this article, I examine Beckettian universal values of Enlightenment, which will be exposed as self-serving mystifications that rationalize and instrumentalize the meaning of life. In this context, the awareness of the Enlightenment nature of Beckett’s writing in Waiting for Godot will be analysed along with the freedom appeal of his reader as he strives to attain the enlightenment. ‘For enlightenment, all that is needed is freedom.’ (Kant 1991 [1784]) Suppose an individual in the world which is a hard shell that he attempts to toss it away, but for what; to think beyond it, and to relocate him beyond it in order to attain enlightenment. Whenever he looks above into the sky, the high sky, the clouds, the flying birds, the stars, the moon, the sun and the cosmos, those make him to forget the hard shell for a while until his eyes fell upon it and he is recaptured. Still into the pupil of his eyes he is reflecting the cosmos. This energy within him, within anyone has vitality and potentiality to reflect the cosmos, and to look beyond the hard shell. Let’s say that he has had an enlightenment experience. Enlightenment is a fact. It is the Truth itself. -

Samuel Beckett's Peristaltic Modernism, 1932-1958 Adam

‘FIRST DIRTY, THEN MAKE CLEAN’: SAMUEL BECKETT’S PERISTALTIC MODERNISM, 1932-1958 ADAM MICHAEL WINSTANLEY PhD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE MARCH 2013 1 ABSTRACT Drawing together a number of different recent approaches to Samuel Beckett’s studies, this thesis examines the convulsive narrative trajectories of Beckett’s prose works from Dream of Fair to Middling Women (1931-2) to The Unnamable (1958) in relation to the disorganised muscular contractions of peristalsis. Peristalsis is understood here, however, not merely as a digestive process, as the ‘propulsive movement of the gastrointestinal tract and other tubular organs’, but as the ‘coordinated waves of contraction and relaxation of the circular muscle’ (OED). Accordingly, this thesis reconciles a number of recent approaches to Beckett studies by combining textual, phenomenological and cultural concerns with a detailed account of Beckett’s own familiarity with early twentieth-century medical and psychoanalytical discourses. It examines the extent to which these discourses find a parallel in his work’s corporeal conception of the linguistic and narrative process, where the convolutions, disavowals and disjunctions that function at the level of narrative and syntax are persistently equated with medical ailments, autonomous reflexes and bodily emissions. Tracing this interest to his early work, the first chapter focuses upon the masturbatory trope of ‘dehiscence’ in Dream of Fair to Middling Women, while the second examines cardiovascular complaints in Murphy (1935-6). The third chapter considers the role that linguistic constipation plays in Watt (1941-5), while the fourth chapter focuses upon peristalsis and rumination in Molloy (1947). The penultimate chapter examines the significance of epilepsy, dilation and parturition in the ‘throes’ that dominate Malone Dies (1954-5), whereas the final chapter evaluates the significance of contamination and respiration in The Unnamable (1957-8). -

The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works Theresa A. Incampo Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Incampo, Theresa A., "The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/209 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical and Sonic Landscapes within the Short Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Submitted by Theresa A. Incampo May 4, 2012 Trinity College Department of Theater and Dance Hartford, CT 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 I: History Time, Space and Sound in Beckett’s short dramatic works 7 A historical analysis of the playwright’s theatrical spaces including the concept of temporality, which is central to the subsequent elements within the physical, metaphysical and sonic landscapes. These landscapes are constructed from physical space, object, light, and sound, so as to create a finite representation of an expansive, infinite world as it is perceived by Beckett’s characters.. II: Theory Phenomenology and the conscious experience of existence 59 The choice to focus on the philosophy of phenomenology centers on the notion that these short dramatic works present the theatrical landscape as the conscious character perceives it to be. The perceptual experience is explained by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as the relationship between the body and the world and the way as to which the self-limited interior space of the mind interacts with the limitless exterior space that surrounds it. -

Naadac Wellness and Recovery in the Addiction

NAADAC WELLNESS AND RECOVERY IN THE ADDICTION PROFESSION 2:00 PM - 3:30 PM CENTRAL MAY 5, 2021 CAPTIONING PROVIDED BY: CAPTIONACCESS [email protected] www.captionaccess.com >> HeLLo, everyone and weLcome to part 5 of 6 of the speciaLty onLine training series on weLLness and recovery. Today's topic is MindfuLness with CLients - Sitting with Discomfort presented by Cary Hopkins Eyles. I'm reaLLy excited to have you guys as part of this presentation. My name is Jessie O'Brien. I'm the training and content manager here at NAADAC the association for addiction professionaLs. And I wiLL be the organizer for today's Learning experience. This onLine training is produced by NAADAC, the association for addiction professionaLs. CLosed captioning is provided by CaptionAccess today. So pLease check your most recent confirmation emaiL for a key Link to use closed captioning. As many of you know, every NAADAC onLine speciaLty series has its own webpage that houses everything you need to know about that particuLar series. If you missed a part of the series and decide to pursue the certificate of achievement you can register for the training that you missed, ticket on demand at your own pace, make the payment and take the quiz. You must be registered for any NAADAC training in order to access the quiz and get the credit. If you want any more information on the weLLness and recovery series, you can find it right there at that page. So this training today is approved for 1.5 continuing education hours, and our website contains a fuLL List of the boards and organizations that approve us as continuing education providers. -

Beckett and Nothing with the Negative Spaces of Beckett’S Theatre

8 Beckett, Feldman, Salcedo . Neither Derval Tubridy Writing to Thomas MacGreevy in 1936, Beckett describes his novel Murphy in terms of negation and estrangement: I suddenly see that Murphy is break down [sic] between his ubi nihil vales ibi nihil velis (positive) & Malraux’s Il est diffi cile à celui qui vit hors du monde de ne pas rechercher les siens (negation).1 Positioning his writing between the seventeenth-century occasion- alist philosophy of Arnold Geulincx, and the twentieth-century existential writing of André Malraux, Beckett gives us two visions of nothing from which to proceed. The fi rst, from Geulincx’s Ethica (1675), argues that ‘where you are worth nothing, may you also wish for nothing’,2 proposing an approach to life that balances value and desire in an ethics of negation based on what Anthony Uhlmann aptly describes as the cogito nescio.3 The second, from Malraux’s novel La Condition humaine (1933), contends that ‘it is diffi cult for one who lives isolated from the everyday world not to seek others like himself’.4 This chapter situates its enquiry between these poles of nega- tion, exploring the interstices between both by way of neither. Drawing together prose, music and sculpture, I investigate the role of nothing through three works called neither and Neither: Beckett’s short text (1976), Morton Feldman’s opera (1977), and Doris Salcedo’s sculptural installation (2004).5 The Columbian artist Doris Salcedo’s work explores the politics of absence, par- ticularly in works such as Unland: Irreversible Witness (1995–98), which acts as a sculptural witness to the disappeared victims of war. -

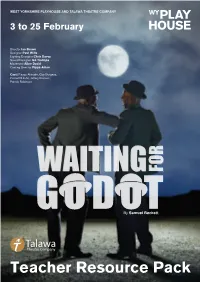

Waiting for Godot’

WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE AND TALAWA THEATRE COMPANY 3 to 25 February Director Ian Brown Designer Paul Wills Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Ian Trollope Movement Aline David Casting Director Pippa Ailion Cast: Fisayo Akinade, Guy Burgess, Cornell S John, Jeffery Kissoon, Patrick Robinson By Samuel Beckett Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Hello and welcome to the West Yorkshire Playhouse and Talawa Theatre Company’s Educational Resource Pack for their joint Production of ‘Waiting for Godot’. ‘Waiting for Godot’ is a funny and poetic masterpiece, described as one of the most significant English language plays of the 20th century. The play gently and intelligently speaks about hardship, friendship and what it is to be human and in this unique Production we see for the first time in the UK, a Production that features an all Black cast. We do hope you enjoy the contents of this Educational Resource Pack and that you discover lots of interesting and new information you can pass on to your students and indeed other Colleagues. Contents: Information about WYP and Talawa Theatre Company Cast and Crew List Samuel Beckett—Life and Works Theatre of the Absurd Characters in Waiting for Godot Waiting for Godot—What happens? Main Themes Extra Activities Why Godot? why now? Why us? Pat Cumper explains why a co-production of an all-Black ‘Waiting for Godot’ is right for Talawa and WYP at this time. Interview with Ian Brown, Director of Waiting for Godot In the Rehearsal Room with Assistant Director, Emily Kempson Rehearsal Blogs with Pat Cumper and Fisayo Akinade More ideas for the classroom to explore ‘Waiting For Godot’ West Yorkshire Playhouse / Waiting for Godot / Resource Pack Page 1 Company Information West Yorkshire Playhouse Since opening in March 1990, West Yorkshire Playhouse has established a reputation both nationally and internationally as one of Britain’s most exciting producing theatres, winning awards for everything from its productions to its customer service. -

Rhythms in Rockaby: Ways of Approaching the Unknowable

83 Rhythms in Rockaby: Ways of Approaching the Unknowable. Leonard H. Knight Describing Samuel Beckett's later, and progressively shorter, pieces in a word is peculiarly difficult. The length of the average critical commentary on them testifies to this, and is due largely to an unravelling of compression in the interests of meaning: straightening out a tightly C9iled spring in order to see how it is made. The analogy, while no more exact than any analogy, is useful at least in suggesting two things: the difficulty of the endeavour; and the feeling, while engaged in it, that it may be largely counterproductive. A straightened out spring, after all, is no longer a spring. Aware of the pitfalls I should nevertheless like, in this paper, to look at part of the mechanism while trying to keep its overall shape relatively intact. The ideas in a Beckett play emerge, in general, from an initial image. A woman half-buried in a grass mound. A faintly spotlit, endlessly talking mouth. Feet tracing a fixed, unvarying path. Concrete and intensely theatrical, the image is immediately graspable. Its force and effectiveness come, above all, from its simpl icity. Described in this way Beckett's images sound arresting to the point of sen sationalism. What effectively lowers the temperature while keeping the excitement generated by their o.riginality is the simple fact that they cannot easily be made out. They are seen, certainly - but only just. In the dimmest possible light; the absolute minimum commensurate with sight. What is initially seen is only then augmented or reinforced by what is said.