How Ecology and Land Use History Shaped the Battle of Chancellorsville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Christopher Ahs 2013.Pdf

WITHOUT A PEDESTAL: THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF JAMES LONGSTREET BY CHRISTOPHER MARTIN SEPTEMBER/2012 Copyright © 2012 Christopher Martin All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………. 1 Context and goals of the study 2. THE LITERATURE AND LEGACY…….……………………………….. 6 Early historical texts Descendents of Southern mythology Shaara turns the page Detangling the history Ambition or ego 3. MAN OF THE SOUTH ……………………………………..….…….…. 33 Longstreet’s early years Personal independence Lack of an identity Intelligent yet not scholarly Accomplished leader 4. A CAREER WORTHY OF PRAISE……………………………………… 45 Blackburn’s Ford Second Manassas Fredericksburg Command and control Chickamauga The Wilderness iii His own rite 5. A BATTLE WORTHY OF CONTROVERSY…………………………… 64 Accusations Gettysburg battle narrative Repudiations Assessment 6. NOT A SOUTHERNER………………………………………………… 94 Longstreet after the war The emergence of the Lost Cause The controversy intensifies The Southern Historical Society Papers Longstreet’s last defense 7. SUBSIDIARY IMMORTALITY………………………………………… 108 Summary Room for further study BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………… 115 iv ABSTRACT Generals Robert E. Lee, Thomas Jackson, and James Longstreet composed the leadership of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia for the majority of the Civil War. Yet Longstreet, unlike Lee and Jackson, was not given appropriate postwar recognition for his military achievements. Throughout American history, critics have argued that Longstreet had a flawed character, and a mediocre military performance which included several failures fatal to the Confederacy, but this is not correct. Analysis of his prewar life, his military career, and his legacy demonstrate that Longstreet’s shortcomings were far outweighed by his virtues as a person and his brilliance as a general. -

US HISTORY, January 4

US HISTORY, January 4 • Entry Task: Stretch your memory! Discuss: What do you remember about the battle of Gettysburg? Why was it important? • Announcements: – Today: Review (you’ll need your packets out!) + how does the Civil War end? Crash Course video will introduce some key ideas. – Half of this week & part of next week – Civil War Project (takes the place of a test – work in the library) and prepare for FINALS WARNING: Some disturbing slides on this ppt! Aggressive offensive to crush the rebellion. – War of attrition: South has less manpower… Gen Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan War goal: Preserve Union and later abolish slavery Capture Richmond Don’t allow Confederacy to rest. Napoleonic tactics at first----later “trench warfare” Defend and delay until Union gives up. Quick victories to demoralize Union Alliance with Great Britain Capture Washington, D.C. Defend Richmond Sought decisive battle that would convince the Union it wasn’t worth it Use better military leadership to your advantage and outsmart Union generals. Civil War Battles: 2 Names??? • The Union identifies battles by streams or rivers, the Confederacy names after nearby towns. Eastern Theater Western Theater Theater/Battles 1862 DATE BATTLE VICTOR RESULT July 1861 Bull Run South Union retreats to Wash. D.C. Manasses June 1862 7 Days South Lee stops McClellan from taking Richmond August 1862 Bull Run South Lee stops John Pope from taking Richmond *Sept. 1862 Antietam Draw McClellan stops Lee from taking Washington, D.C. Lincoln issues Emancipation Proclamation *Turning Point battle Gettysburg George Meade Robert E. Lee The Road to Gettysburg: 1863 Gettysburg July 1-3, 1863 Location: Pennsylvania • Lee tries to invade the North again • ¼ of each army lost • Who wins this battle? North – Lee retreats to Virginia • Grant is named Supreme Commander • Map on p. -

James Longstreet and His Staff of the First Corps

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar The Best Staff Officers in the Army- James Longstreet and His Staff of the First Corps Karlton Smith Lt. Gen. James Longstreet had the best staff in the Army of Northern Virginia and, arguably, the best staff on either side during the Civil War. This circumstance would help to make Longstreet the best corps commander on either side. A bold statement indeed, but simple to justify. James Longstreet had a discriminating eye for talent, was quick to recognize the abilities of a soldier and fellow officer in whom he could trust to complete their assigned duties, no matter the risk. It was his skill, and that of the officers he gathered around him, which made his command of the First Corps- HIS corps- significantly successful. The Confederate States Congress approved the organization of army corps in October 1862, the law approving that corps commanders were to hold the rank of lieutenant general. President Jefferson Davis General James Longstreet in 1862. requested that Gen. Robert E. Lee provide (Museum of the Confederacy) recommendations for the Confederate army’s lieutenant generals. Lee confined his remarks to his Army of Northern Virginia: “I can confidently recommend Generals Longstreet and Jackson in this army,” Lee responded, with no elaboration on Longstreet’s abilities. He did, however, add a few lines justifying his recommendation of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson as a corps commander.1 When the promotion list was published, Longstreet ranked as the senior lieutenant general in the Confederate army with a date of rank of October 9, 1862. -

3 the North Wins

TERMS & NAMES 3 TheThe NorthNorth WinsWins Battle of Gettysburg Pickett’s Charge Ulysses S. Grant Robert E. Lee Siege of Vicksburg William Tecumseh MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW Sherman Thanks to victories, beginning with If the Union had lost the war, the Appomattox Court House Gettysburg and ending with United States might look very Richmond, the Union survived. different now. ONE AMERICAN’S STORY Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain was a 32-year-old college professor when the war began. Determined to fight for the Union, he left his job and took command of troops from his home state of Maine. Like most soldiers, Chamberlain had to get accustomed to the carnage of the Civil War. His description of the aftermath of one battle shows how soldiers got used to the war’s violence. A VOICE FROM THE PAST It seemed best to [put] myself between two dead men among the many left there by earlier assaults, and to draw another crosswise for a pillow out of the trampled, blood-soaked sod, pulling the flap of his coat over my face to fend off the chilling winds, and still more chilling, the deep, many voiced moan [of the wounded] that overspread the field. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, quoted in The Civil War During the war, Chamberlain fought in 24 battles. He was wounded six times and had six horses shot out from under him. He is best remembered for his actions at the Battle of Gettysburg, where he In 1862, Joshua Chamberlain was offered a year's travel with pay to courageously held off a fierce rebel attack. -

General Grant's Strategy in the Overland Campaign

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Honors Program Theses and Projects Undergraduate Honors Program 12-11-2020 Challenging the "Butcher" Reputation: General Grant's Strategy in the Overland Campaign Sean Ftizgerald Bridgewater State University Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ftizgerald, Sean. (2020). Challenging the "Butcher" Reputation: General Grant's Strategy in the Overland Campaign. In BSU Honors Program Theses and Projects. Item 442. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/ honors_proj/442 Copyright © 2020 Sean Ftizgerald This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Challenging the "Butcher" Reputation: General Grant's Strategy in the Overland Campaign Sean Fitzgerald Submitted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for Commonwealth Honors in History Bridgewater State University December 11, 2020 Dr. Thomas G. Nester, Thesis Advisor Dr. Brian J. Payne, Committee Member Dr. Meghan Healy-Clancy, Committee Member 1 Figure 1. The Eastern Theater. Ethan Rafuse, Robert E. Lee and the Fall of the Confederacy, 1863-1865 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2009), 10. 2 On March 10, 1864, as the United States prepared to enter its fourth year of civil war, President Abraham Lincoln elevated General Ulysses S. Grant to the position of Commanding General of all Union armies, one day after having bestowed on him the rank of Lieutenant General (a title previously held only by George Washington). Grant had won fame for his string of victories in the Western Theater. In 1862 he had captured Forts Henry and Donelson, enabling the Union to use the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers as routes for invading the South, and had wrestled victory out of a Confederate attack on his army at Shiloh. -

“Battle Hymn of the Republic” Battles and Campaigns

“BATTLE HYMN OF THE REPUBLIC” 36 “Battle Hymn of the Republic” broader goal (such as the capture of an en- The Civil War song “Battle Hymn of the tire peninsula in a certain amount of time). Republic” was extremely popular with Such operations, taken collectively, were Union soldiers, who often sang it while called a campaign (e.g., the Peninsula rallying for battle. The tune, however, pre- Campaign). dates the Civil War as an 1856 Methodist Historians disagree somewhat on which camp-meeting hymn titled “Oh Brothers, battles should be included in a list of the Will You Meet Us on Canaan’s Happy most important Civil War conflicts. How- Shore?” by William Steffe of South Car- ever, the most commonly cited major bat- olina. (It is not known whether he com- tles and campaigns are as follows: posed the lyrics as well as the tune.) The Attack on Fort Sumter. On April Shortly after the war began, a group of 12, 1861, the Confederates fired the first Union soldiers in Boston, Massachusetts, shots of the war when they attacked a fed- composed new lyrics that referred to abo- eral garrison at Fort Sumter, located on litionist John Brown, who had been a man-made island in the middle of hanged in Virginia in 1859 for trying to Charleston Harbor in South Carolina; on lead a slave rebellion. To many people in April 14, after a seige of more than fifty the North, John Brown was a hero, and the hours, the fort fell into Confederate hands. Union soldiers’ lyrics called him “a soldier The First Battle of Bull Run (also in the army of the Lord.” This song, called known as the First Battle of Manassas). -

Chapter VIII GRANT VS LEE

Chapter VIII GRANT VS LEE A. Grant Comes East - Lincoln sends for Grant and gives him total command of all US forces (General-in-chief) and the rank of Lieutenant General (the first person to hold that rank since George Washington). - Grant names Gen. William T. Sherman commander of the western armies and retains Gen. George Meade as the commander of the Army of the Potomac. - Grant changes the military strategy; take on the Confederate Armies until they cease to exist. “Lee’s army will be your objective point, wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.” B. The Battle of the Wilderness May 5 & 6, 1864 USA Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant 101,895 men The Army of the Potomac CSA Gen. Robert E. Lee 61,025 men The Army of Northern Virginia Day 1 – Grant attempts to cross into the wilderness just as Hooker did the previous year. Grant finds the wilderness very difficult to move an army through and Lee takes advantage of Grant’s position to attack him. Lee attacks with 2 Corps but the wilderness makes it too difficult to carry out a coordinated attack. Day 2 – - Both armies attack the opponent’s other flank but as the day wears on Hancock’s Corps breaks the Confederate line. - Just as Hancock is about to take advantage of the break, Longstreet’s Corps arrives. - Lee grabs a flag and begins to personally lead the counter-attack. - The troops refuse to attack until Lee moves out of harm’s way. - Longstreet convinces him, followed immediately by Longstreet’s attack which plugs the break. -

FREDERICKSBURG, and Spotsyllvania NATIONAL MILITARY PARK to Wanenton to Washington

Here, midway between Washington and Rich- was a good one-so logical, in fact, that Lee an- mond, Union and Confederate armies fought ticipated it. He, too, left a holding force behind four major battles: Fredericksburg, Chancellors- and moved most of his army upriver to concen- ville, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court trate around Chancellorsville, a crossroads 10 House. The Confederates won the first two. miles from Fredericksburg. Surprised, Hooker After the last two engagements, Federal troops went into a defensive position, leaving his right continued a drive that eventually culminated in flank unprotected. On May 2, Lee again divided the destruction of the Confederate Army of his army and sent Stonewall Jackson around the Northern Virginia. Union front to attack the right. Jackson rolled up the Union flank, but the day ended tragically Thewar'sfirst"On to Richmond" campaign failed for the Confederates. That night Jackson was in July 1861, as shattered Union troops streamed accidentally shot by his own men. He died 8 days back into the Washington defenses from the later at Guiney's Station on the R.F. & P. Railroad. Battle of First Manassas. The second thrust, up the Peninsula between the James and the York On May 3, Lee lashed out against Hooker's newly Rivers during the spring and summer of 1862, formed lines and drove them toward the river. ended with the Seven Days' Battles before Rich- But in Fredericksburg Union troops pushed back mond and the return of the Union army to Wash- the Confederates and moved westward. Once ington. A third push in the late summer of 1862 more Lee divided his small army and hurried resulted in the Confederate victory of Second toward the town. -

Stonewall Jackson Shrine Battle of the Wilderness Battle of Chancellorsville Battle of Fredericksburg Battle of Spotsylvania

RIVER AN ID P A R Germanna R Ford A P P A H A N N O C K RAPID AN North 0 1 2 Kilometers ad ilro 0 1 2 Miles c Ra oad oma ilr nd Pot To Ra sburg a POTOMAC SX rick CREEK Washington, DC C ede 17 Fr 1 1 1 1 Tour stop d, on m h ic R S Route connecting Park property p c o i t Exit 133 r s o park areas d w t a s o i o o R d H 3 n d F Picnic area Scenic easement G r u u r e o n r R F a m c BUS s 610 S e a s U n R 17 n e o n a 618 ORANGE COUNTY a d Interpretive Land authorized r H e ig d trail for future park h l Battle of E w i ly C a s 616 NO K acquisition y W AN Fo AH RI Chancellorsville rd P V Grant’s P E R o 620 A R Headquarters April 27–May 6, 1863 a R Do not use this map to 20 d FALMOUTH Possession or use of ad Wilderness Battlefield R Ro 1 Wilderness ive s r metal detectors on park determineain park bound- Tavern site Chancellorsville R Pl Exhibit Shelter o lle a 212 property is illegal. Be aries. Check at park d Scott’s Ford/Ferry Battlefield 2 Ellwood (inaccessible) headquarters or visitor 613 Visitor Center d Bullock House Site (Lacy House) R BUS centers for accurate 3 Saunders Field k oc 2 enue 1 (open seasonally) d 8 ll l Av u Hil boundary information. -

THE ROSE GARDEN at ARLINGTON HOUSE ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY by George W

THE ROSE GARDEN AT ARLINGTON HOUSE ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY By George W. Dodge The Garden's First Burial Captain Albert H. Packard, Company I, 31st Maine Infantry; Company G, 19th Maine Infantry The first soldier buried alongside the Rose Garden at Arlington House, home of Robert E. Lee and his family for thirty years before the Civil War, was Captain Albert Packard of the 31st Maine Infantry. According to cemetery burial records, Captain Packard is the first officer and the first soldier from a Maine regiment buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Packard, the twenty-fourth burial at Arlington, was buried on Tuesday May 17, 1864, the fifth day of burials there. 1 On August 25, 1862, Albert Packard, age thirty, departed from his wife, two children and mechanic's job to enroll in the 19th Maine. 2 After four weeks of training in Maine, Packard and his regiment arrived in Washington, D.C. on August 29, 1862. On October 16, 1862, while on a reconnaissance at Charlestown, Virginia [now West Virginia] the regiment came under gun · fire for the first time. 3 By October 31, 1862, Packard was a corporal in Company G. His duties included that of color bearer. 4 Following a winter of camp, drill and illness, Packard was among the 440 members of the 19th Maine who marched north and were engaged at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 1-3, 1863. Packard's regiment sustained over 45 percent casualties at Gettysburg, 68 killed or mortally wounded, 127 wounded and 4 missing.5 In February 1864, Packard returned to Maine to recruit soldiers for a new regiment, the 31st Maine. -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

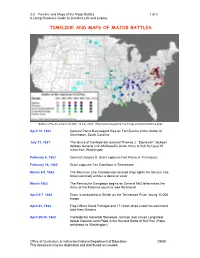

Timeline and Maps of Major Battles

3-3 Timeline and Maps of the Major Battles 1 of 3 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy TIMELINE AND MAPS OF MAJOR BATTLES Battles of the American Civil War. 18 July 2008. <http://www.wisegorilla.com/images/civilwar/0-battles.png> April 12, 1861 General Pierre Beauregard fires on Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina July 21, 1861 The forces of Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson defeats General Irvin McDowell’s Union Army at Bull Run just 25 miles from Washington February 6, 1862 General Ulysses S. Grant captures Fort Henry in Tennessee February 16, 1862 Grant captures Fort Donelson in Tennessee March 8/9, 1862 The Merrimac (the Confederate ironclad ship) fights the Monitor (the Union ironclad) without a decisive victor March 1862 The Peninsular Campaign begins as General McClellan takes the Army of the Potomac south to take Richmond April 6-7, 1862 Grant is ambushed at Shiloh on the Tennessee River, losing 13,000 troops April 24, 1862 Flag Officer David Farragut and 17 Union ships under his command take New Orleans April 29-30, 1862 Confederate Generals Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet defeat General John Pope in the Second Battle of Bull Run (Pope withdraws to Washington) Office of Curriculum & Instruction/Indiana Department of Education 09/08 This document may be duplicated and distributed as needed. 3-3 Timeline and Maps of the Major Battles 2 of 3 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy May 31, 1862 Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston nearly defeats McClellan’s