Flaming Gorge Operation Plan - May 2021 Through April 2022

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State of Outdoor Recreation in Utah 2020 a High-Level Review of the Data & Trends That Define Outdoor Recreation in the State

the State of outdoor recreation in utah 2020 A high-level review of the data & trends that define outdoor recreation in the state. Jordan W. Smith, Ph.D. & Anna B. Miller, Ph.D. Institute of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, Utah State University about the Institute The Institute of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism (IORT) was founded in 1998 by the Utah State Legisla- ture through the Recreation and Tourism Research and Extension Program Act (S.B. 35). It is mandated to focus on: tourism and outdoor recreation use; the social and economic tradeoffs of tourism and outdoor recreation for local communities; and the relationship between outdoor recreation and tourism and pub- lic land management practices and policies. The purpose of the Institute is to provide: better data for the Legislature and state agencies in their deci- sion-making processes on issues relating to tourism and outdoor recreation; a base of information and expertise to assist community officials as they attempt to balance the economic, social, and environmen- tal tradeoffs in tourism development; and an interdisciplinary approach of research and study on outdoor recreation and tourism, a complex sector of the state’s economy. The Institute is composed of an interdisciplinary team of scientists with backgrounds in the economic, psychological, social, and spatial sciences. It is led by Dr. Jordan W. Smith (Director), Dr. Anna B. Miller (Assistant Director of Research and Operations), and Chase C. Lamborn (Assistant Director of Outreach and Education). The Institute delivers on its mission through a broad network of Faculty Fellows. Jordan W. Smith, Ph.D.1, is the Director of the Institute of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism and an As- sistant Professor in the Department of Environment and Society at Utah State University. -

Operation of Flaming Gorge Dam Final Environmental Impact Statement

Record of Decision Operation of Flaming Gorge Dam Final Environmental Impact Statement I. Summary of Action and Background The Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) has completed a final environmental impact statement (EIS) on the operation of Flaming Gorge Dam. The EIS describes the potential effects of modifying the operation of Flaming Gorge Dam to assist in the recovery of four endangered fish, and their critical habitat, downstream from the dam. The four endangered fish species are Colorado pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus lucius), humpback chub (Gila cypha), razorback sucker (Xyrauchen texanus), and bonytail (Gila elegans). Reclamation would implement the proposed action by modifying the operations of Flaming Gorge Dam, to the extent possible, to achieve the flows and temperatures recommended by participants of the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program (Recovery Program). Reclamation’s goal is to implement the proposed action and, at the same time, maintain and continue all authorized purposes of the Colorado River Storage Project. The purpose of the proposed action is to operate Flaming Gorge Dam to protect and assist in recovery of the populations and designated critical habitat of the four endangered fishes, while maintaining all authorized purposes of the Flaming Gorge Unit of the Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP), including those related to the development of water resources in accordance with the Colorado River Compact. As the Federal agency responsible for the operation of Flaming Gorge Dam, Reclamation was the lead agency in preparing the EIS. Eight cooperating agencies also participated in preparing this EIS: the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, State of Utah Department of Natural Resources, U.S. -

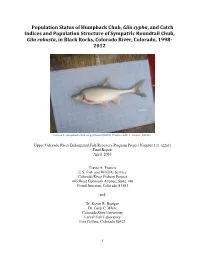

Population Status of Humpback Chub, Gila Cypha, and Catch

Population Status of Humpback Chub, Gila cypha, and Catch Indices and Population Structure of Sympatric Roundtail Chub, Gila robusta, in Black Rocks, Colorado River, Colorado, 1998- 2012 Picture 1. Humpback chub on grid board (2012). Photo credit: T. Francis, USFWS. Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program Project Number 131 (22a3) Final Report April, 2016 Travis A. Francis U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Colorado River Fishery Project 445 West Gunnison Avenue, Suite 140 Grand Junction, Colorado 81501 -and- Dr. Kevin R. Bestgen Dr. Gary C. White Colorado State University Larval Fish Laboratory Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 i Suggested Citation: Francis, T.A., K.R. Bestgen, and G.C. White. 2016. Population status of humpback chub, Gila cypha, and catch indices and population structure of sympatric roundtail chub, Gila robusta, in Black Rocks, Colorado River, Colorado, 1998-2012. Larval Fish Laboratory Contribution 199. Final Report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program, Project Number 131. Grand Junction, Colorado. ii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... -

Big-River Monitoring on the Colorado Plateau

I NVENTORY & M ONITORING N ETWORK Big-River Monitoring on the Colorado Plateau Dustin Perkins1, Mike Scott2, Greg Auble2, Mark Wondzell3, Chris Holmquist-Johnson2, Eric Wahlig2, Helen Thomas1, and Aneth Wight1; 1Northern Colorado Plateau Network, P.O. Box 848, Bldg. 11, Arches National Park, Moab, UT 84532 2U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Discipline, FORT Science Center, 2150 Centre Ave., Building C, Fort Collins, CO 80526; 3National Park Service, Water Resources Division, 1201 Oakridge Dr., Ste. 150, Fort Collins, CO 80525 Introduction and Green rivers in Canyonlands National Park. The Yampa River is the longest relatively free-flowing river Water has always been in short supply in the western reach remaining in the Colorado River basin. The U.S., making it a consistent source of conflict. In Green River is highly regulated by Flaming Gorge Dam the Colorado River drainage, an increasing human but is partially restored below its confluence with the population fuels increased demands for water from Yampa River. There have been large-scale changes the river and its tributaries. As a result, streamflow to the Green River since Flaming Gorge Dam was in virtually all of these systems has been altered by completed in 1962. reservoirs and other water-development projects. In most cases, reduced flows have significantly altered Monitoring of these rivers and their riparian peak flows and increased base flows that structure vegetation focuses on processes that affect the river floodplain vegetation, stream-channel morphology, channel, active bars, and riparian floodplains. To get and water quality (e.g., temperature, suspended a complete picture of river conditions, the NCPN sediment, nutrients). -

The Impact of the Endangered Species Act on Glen Canyon Dam Operations and Stakeholders

The Bottom Line: The Impact of the Endangered Species Act on Glen Canyon Dam Operations and Stakeholders By Leslie James he Endangered Species Act (ESA) is arguably the most powerful environmental law ever enacted. Since its passage in 1973, it has had far-reaching Timpacts on power production from federally owned multiple-purpose projects, such as the Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP). Operational changes resulting from efforts to address ESA issues impact not only power production but repayment of the federal investment in the project. While differing approaches and programs have been established in an attempt to address ESA issues at Glen Canyon Dam, operations have proved to be significant and costly. Background: Colorado River Storage Project In 1956, Congress passed the Colorado River Storage Glen Canyon Dam. Project Act to provide storage facilities for the Upper Basin states so that they could meet Colorado River Compact needs. Operated by the Bureau of Reclamation, the CRSP of total CRSP generation. Flaming Gorge Dam is on the consists of multipurpose dams that release water to meet Green River, a major tributary of the Colorado River, and Colorado River Compact, municipal and industrial (M&I), has three units producing about 132 MW of generation. and irrigation requirements. As the water is released, electric power and energy are produced to help pay for ESA Impacts on Glen Canyon Dam Operations the projects. The Western Area Power Administration The Glen Canyon Dam power plant generates power (WAPA) markets and transmits that electricity to for municipal, industrial, irrigation pumping, and other preference power entities pursuant to federal law. -

Floating the Green River

Green River Campsites How to get to the Green River All established campgrounds include a table, fire ring, tent pads and benches. River mileages are given beginning at Flaming Gorge Dam. For availability and reservations go to www.reserveUSA.com. All other From Wyoming campsites are on a first come basis. From I-80 just west of Rock The Green River from Little Hole to the Springs, WY, take US-191 to exit 99, travel south to the Utah/Colorado state line is a quiet stretch of major access points at Clay Basin or Dutch John, UT. 1. Stonefly I & II 10. Big Pine Camp I & II 18. Bridge Port Camp 27. Pipeline Camp river surrounded by beautiful scenery, wildlife (FS) North side (river left) (FS) North side (river left) (State) North side (river left) (BLM) East side (river left) Green River Camping From Salt Lake City Mile 8.2. Mile 10.5. Mile 17.3. Mile 22. Take I-80 to exit 34, follow Camping between Little Hole and Indian Crossing and outstanding opportunities for recreation the signs from Fort Bridger to 11. Pugmire Pocket Camp is restricted to designated float-in or hike-in campsites. Manila, UT, then take UT-44 2. Sand Camp 19. River Bend Camp 28. Little Swallow Camp and adventure. Whether you’re interested in (FS) North side (river left) (BLM) South side (river right) (BLM) South side (river right) (BLM) East side (river left) Campers must pack-in/pack-out all trash and build fires to the intersection with US-191. US-191 leads to Mile 8.3. -

Itinerary: the Yampa River: 5 Days/4 Nights

Itinerary: PO Box 1324 Moab, UT 84532 (800) 332-2439 The Yampa River: (435) 259-8229 Fax (435) 259-2226 Email: [email protected] 5 Days/4 Nights www.GriffithExp.com T h r o u g h Dinosaur National Monument O v e r v i e w of The Yampa River Meeting Place Best Western Antlers 423 West Main Street Vernal, UT 84078 Meeting Time : 6 : 3 0 pm (MDT) The evening before your trip Orientation: 6 : 3 0 pm (MDT) the day BEFORE d e p a r t u r e H e r e you will learn what to expect and prepare for, receive your dry bags, sign Assumption of Risk forms, and get a chance to ask last minute q u e s t i o n s . Morning Place : Best Western Antlers 423 West Main Street Vernal, UT 84078 M o r n i n g T i m e : 7 : 0 0 a m (MDT) Return Time : Approximately 5 : 0 0 - 6 : 0 0 P M Rapid Rating: C l a s s I I I - I V (water level dependent) # of Rapids : 16 River Miles: 72 P u t i n : Deer Lodge Park Ranger Station T a k e - out : Split Mountain boat ramp Trip Length: 5 D a y s / 4 N i g h t s Raft Type(s): O a r b o a t s , Paddleboats and Inflatable Kayaks Age Limit: Minimum Age is 10 y e a r s o l d What makes this trip special? The Yampa River through the Dinosaur National Monument has it all! As the last free-flowing river in the entire Colorado River drainage, the Yampa is incredibly wild in May and June. -

Razorback Suckers Are Making a Comeback in the Upper Colorado River Basin

Winter 13 Razorback suckers are making a comeback in the upper Colorado River basin iologists are thrilled that the recovery programs’ stocking Hatchery programs have been very successful. In the upper efforts are bearing fruit and razorback suckers are becom- basin, razorback suckers are being raised by the Ouray National Bing more numerous throughout the upper Colorado River Fish Hatchery, Randlett and Grand Valley units near Vernal, Utah basin. “We catch so many razorbacks these days; it takes us lon- and Grand Junction, Colorado. Following analysis of razorback ger to complete our Colorado pikeminnow sampling trips,” says sucker stocking and survival by Colorado State University’s Larval U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) researcher Travis Francis. Fish Lab, the Recovery Program increased the size of razorback Historically, the razorback sucker occurred throughout warm- sucker for stocking from an average of about 11 inches to about 14 water reaches of the Colorado River Basin from Mexico to Wyoming. PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY UDWR-MOAB inches and is stocking the fish in the fall when fish survive better. When this species was listed in 1991, its numbers were much reduced To increase growth, the Program raises the fish in a combination and biologists were worried it might become extinct. Thanks to of outdoor ponds during warmer months and indoor tanks in the the efforts of the San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation winter. Program and the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery This past summer, many wild-spawned razorback larvae drift- Program, these fish are making a real comeback today. Hatchery- ed from a middle Green River spawning bar into the Stewart Lake produced fish are being stocked to re-establish the species in the JUVENILE RAZORBACK SUCKER, MAY, 2013 wetland about 11 miles downstream. -

Navajo Reservoir and San Juan River Temperature Study 2006

NAVAJO RESERVOIR AND SAN JUAN RIVER TEMPERATURE STUDY NAVAJO RESERVOIR BUREAU OF RECLAMATION 125 SOUTH STATE STREET SALT LAKE CITY, UT 84138 Navajo Reservoir and San Juan River Temperature Study Page ii NAVAJO RESERVOIR AND SAN JUAN RIVER TEMPERATURE STUDY PREPARED FOR: SAN JUAN RIVER ENDANGERED FISH RECOVERY PROGRAM BY: Amy Cutler U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Upper Colorado Regional Office FINAL REPORT SEPTEMBER 1, 2006 ii Navajo Reservoir and San Juan River Temperature Study Page iii TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................3 2. OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................5 3. MODELING OVERVIEW .......................................................................................6 4. RESERVOIR TEMPERATURE MODELING ......................................................7 5. RIVER TEMPERATURE MODELING...............................................................14 6. UNSTEADY RIVER TEMPERATURE MODELING........................................18 7. ADDRESSING RESERVOIR SCENARIOS USING CE-QUAL-W2................23 7.1 Base Case Scenario............................................................................................23 7.2 TCD Scenarios...................................................................................................23 -

Colorado Pikeminnow: Forgotten Predator of the Lower Colorado River

Colorado Pikeminnow: Forgotten Predator of the Lower Colorado River David Ward US Geological Survey Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center Outline • Historical context • A common misperception about Colorado Pikeminnow • Political Context • A Call to Action Historical Context Celebration at completion of Laguna Dam 1909 Concrete Cap on Laguna Dam stretching from CA to AZ Catching Colorado pikeminnow above Hoover Dam c.1938 Last Colorado pikeminnow captured in Lake Mohave, November 13, 1962 1976 last pikeminnow caught in Grand Canyon at Havasu Creek A Common Misperception • Colorado Pikeminnow will cause detrimental impacts to other endangered fish Conservation efforts through predation Flathead Catfish Smallmouth Bass Bullhead Catfish Colorado Pikeminnow Body depth of Humpback Chub Body depth of Razorback Sucker Why Have they Been forgotten? •2002 Recovery Goals stated that no Conservation actions downstream of Glen Canyon Dam count toward species recovery • This decision was to be re- evaluated during 5-year status reviews - but has not occurred Adult Pikeminnow persist in the Verde River, but no research is conducted because no money is available The River is too disjunct! Segregated native fish management Marsh and Pacey 2005 Clarkson et al. 2005 Mueller 2005 If we are not going to pursue segregated fish management Which of our native fish are likely to persist with Non-native fishes? Colorado Pikeminow – one of best candidates Conclusions • Gape comparisons indicate Pikeminnow pose little threat relative to other introduced predatory fishes (and they have no teeth) • Arguments against repatriation based on fears of potential negative impacts to other endangered native fishes may be overstated • Without revision of the recovery goals the fate of Colorado Pikeminnow in the Lower Colorado River basin may be sealed. -

Yampa River Is Placed on Call for 1St Time Ever | Steamboattoday.Com 8/12/20, 9�43 AM

Yampa River is placed on call for 1st time ever | SteamboatToday.com 8/12/20, 943 AM YOUR AD HERE » Yampa River is placed on call for 1st time ever News FOLLOW NEWS | September 5, 2018 Eleanor C. Hasenbeck FOLLOW [email protected] The Yampa River flows through Dinosaur National Monument around Aug. 18. Low flows in the lower stretch of the river led water managers to curtail some use of water from the river. (courtesy photo) STEAMBOAT SPRINGS — For the first time, water users on the main stem of the Yampa River have been curtailed. Due to low water conditions in the lower stretch of the river near Dinosaur National Monument, the Colorado Division of Water Resources placed a call on the river Tuesday. The call applies to water users upstream from the river’s lowest diversion point, which essentially places the entire river on call. https://www.steamboatpilot.com/news/yampa-river-is-placed-on-call-for-1st-time-ever/ Page 1 of 4 Yampa River is placed on call for 1st time ever | SteamboatToday.com 8/12/20, 943 AM “We are now faced again with the Yampa River being extremely low at its lower end, and we are unable to both protect the Endangered Fishes Recovery Program reservoir water and allow all water users to continue to divert water,” Erin Light, the area division engineer, wrote in an email to water users in the Yampa River Basin on Wednesday morning. The Division of Water Resources places a call on a stream when water rights owners do not receive the amount of water they have a legal right to. -

Ashley National Forest Visitor's Guide

shley National Forest VISITOR GUIDE A Includes the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area Big Fish, Ancient Rocks Sheep Creek Overlook, Flaming Gorge Painter Basin, High Uinta Wilderness he natural forces that formed the Uinta Mountains are evident in the panorama of geologic history found along waterways, roads, and trails of T the Ashley National Forest. The Uinta Mountains, punctuated by the red rocks of Flaming Gorge on the east, offer access to waterways, vast tracts of backcountry, and rugged wilderness. The forest provides healthy habitat for deer, elk, What’s Inside mountain goats, bighorn sheep, and trophy-sized History .......................................... 2 trout. Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, the High Uintas Wilderness........ 3 Scenic Byways & Backways.. 4 Green River, High Uintas Wilderness, and Sheep Creek Winter Recreation.................... 5 National Geological Area are just some of the popular Flaming Gorge NRA................ 6 Forest Map .................................. 8 attractions. Campgrounds ........................ 10 Cabin/Yurt Rental ............... 11 Activities..................................... 12 Fast Forest Facts Know Before You Go .......... 15 Contact Information ............ 16 Elevation Range: 6,000’-13,528’ Unique Feature: The Uinta Mountains are one of the few major ranges in the contiguous United States with an east-west orientation Fish the lakes and rivers; explore the deep canyons, Annual Precipitation: 15-60” in the mountains; 3-8” in the Uinta Basin high peaks; and marvel at the ancient geology of the Lakes in the Uinta Mountains: Over 800 Ashley National Forest! Acres: 1,382,347 Get to Know Us History The Uinta Mountains were named for early relatives of the Ute Indians. or at least 8,000 years, native peoples have Sapphix and son, Ute, 1869 huntedF animals, gathered plants for food and fiber, photo courtesy of First People and used stone tools, and other resources to make a living.