The State of Outdoor Recreation in Utah 2020 a High-Level Review of the Data & Trends That Define Outdoor Recreation in the State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flaming Gorge Operation Plan - May 2021 Through April 2022

Flaming Gorge Operation Plan - May 2021 through April 2022 Concurrence by Kathleen Callister, Resources Management Division Manager Kent Kofford, Provo Area Office Manager Nicholas Williams, Upper Colorado Basin Power Manager Approved by Wayne Pullan, Upper Colorado Basin Regional Director U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation • Interior Region 7 Upper Colorado Basin • Power Office Salt Lake City, Utah May 2021 Purpose This Flaming Gorge Operation Plan (FG-Ops) fulfills the 2006 Flaming Gorge Record of Decision (ROD) requirement for May 2021 through April 2022. The FG-Ops also completes the 4-step process outlined in the Flaming Gorge Standard Operation Procedures. The Upper Colorado Basin Power Office (UCPO) operators will fulfil the operation plan and may alter from FG-Ops due to day to day conditions, although we will attempt to stay within the boundaries of the operations defined below. Listed below are proposed operation plans for four different scenarios: moderately dry, average (above median), average (below median), and moderately wet. As of the publishing of this document, the most likely scenario is the moderately dry, however actual operations will vary with hydrologic conditions. The Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program (Recovery Program), the Flaming Gorge Technical Working Group (FGTWG), Flaming Gorge Working Group (FG WG), United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) provided input that was considered in the development of this report. The FG-Ops describes the current hydrologic classification of the Green River Basin and the hydrologic conditions in the Yampa River Basin. The FG-Ops identifies the most likely Reach 2 peak flow magnitude and duration that is to be targeted for the upcoming spring flows. -

Ashley National Forest Visitor's Guide

shley National Forest VISITOR GUIDE A Includes the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area Big Fish, Ancient Rocks Sheep Creek Overlook, Flaming Gorge Painter Basin, High Uinta Wilderness he natural forces that formed the Uinta Mountains are evident in the panorama of geologic history found along waterways, roads, and trails of T the Ashley National Forest. The Uinta Mountains, punctuated by the red rocks of Flaming Gorge on the east, offer access to waterways, vast tracts of backcountry, and rugged wilderness. The forest provides healthy habitat for deer, elk, What’s Inside mountain goats, bighorn sheep, and trophy-sized History .......................................... 2 trout. Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, the High Uintas Wilderness........ 3 Scenic Byways & Backways.. 4 Green River, High Uintas Wilderness, and Sheep Creek Winter Recreation.................... 5 National Geological Area are just some of the popular Flaming Gorge NRA................ 6 Forest Map .................................. 8 attractions. Campgrounds ........................ 10 Cabin/Yurt Rental ............... 11 Activities..................................... 12 Fast Forest Facts Know Before You Go .......... 15 Contact Information ............ 16 Elevation Range: 6,000’-13,528’ Unique Feature: The Uinta Mountains are one of the few major ranges in the contiguous United States with an east-west orientation Fish the lakes and rivers; explore the deep canyons, Annual Precipitation: 15-60” in the mountains; 3-8” in the Uinta Basin high peaks; and marvel at the ancient geology of the Lakes in the Uinta Mountains: Over 800 Ashley National Forest! Acres: 1,382,347 Get to Know Us History The Uinta Mountains were named for early relatives of the Ute Indians. or at least 8,000 years, native peoples have Sapphix and son, Ute, 1869 huntedF animals, gathered plants for food and fiber, photo courtesy of First People and used stone tools, and other resources to make a living. -

Utah Water Science Center

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Utah Water Science Center Upper Colorado River Streamflow and Reservoir Contents Provisional Data for: WATER YEAR 2019 All data contained in this report is provisional and subject to revision. Available online at usgs.gov/centers/ut-water PROVISIONAL DATA U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SUBJECT TO REVISION UTAH WATER SCIENCE CENTER STREAMFLOW AND RESERVOIR CONTENTS IN UPPER COLORADO RIVER BASIN DAYS IN contact 435-259-4430 or [email protected] MONTH October 2018 31 MONTHLY DISCHARGE (a) MAXIMUM DAILY MINIMUM DAILY (A)MEDIAN PERCENT TOTAL 3 3 3 3 3 STREAM ft /s MEAN ft /s 30 YEAR ft /s ACRE ft /s DATE ft /s DATE (1981-2010) THIS MONTH MEDIAN DAYS FEET COLORADO RIVER NR CISCO, UTAH 4,355 3,202 74% 99,433 196,878 5,090 8-Oct 1,990 1-Oct ADJUSTED (B) 2,638 61% 81,764 162,178 GREEN RIVER AT GREEN RIVER , UT 2,945 2,743 93% 85,031 168,362 3,430 6-Oct 2,030 1-Oct ADJUSTED (C) 1,889 64% 58,564 116,162 SAN JUAN RIVER NEAR BLUFF, UT 1,232 649 53% 20,164 39,924 1,010 7-Oct 429 6-Oct ADJUSTED (D) 391 32% 12,112 24,024 DOLORES RIVER NR CISCO, UTAH 237 123 52% 3,565 7,058 493 8-Oct 22 1-Oct ADJUSTED (E) 141 60% 4,373 8,673 (A) MEDIAN OF MEAN DISCHARGES FOR THE MONTH FOR 30-YR PERIOD 1981-2010 (B) ADJUSTED FOR CHANGE IN STORAGE IN BLUE MESA RESERVOIR. -

FINAL Retrospective Analysis of Water Temperature Data and Larval And

FINAL Retrospective analysis of water temperature data and larval and young of year fish collections in the San Juan River downstream from Navajo Dam to Lake Powell Utah Prepared for: Ecosystems Research Institute Logan, Utah And U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Salt Lake City, Utah Prepared by: William J. Miller And Kristin M. Swaim Miller Ecological Consultants, Inc PO Box 1383 Bozeman, Montana 59771 February 14, 2017 Final San Juan River Water Temperature Retrospective Report February 14, 2017 Executive Summary Miller Ecological Consultants conducted a retrospective analysis of existing San Juan River water temperature datasets and larval fish data. Water temperature data for all years available were evaluated in conjunction with the timing and number of larvae captured in the annual larval fish monitoring surveys that are required by the San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program (SJRBRIP) Long Range Plan. Under the guidance of the SJRBRIP, Navajo Dam experimental releases were conducted and evaluated from 1992-1998. After this research period, the SJRBRIP completed the flow recommendations. The SJRBRIP established flow recommendations for the San Juan River designed to maintain or improve habitat for endangered Colorado Pikeminnow Ptychocheilus lucius and Razorback Sucker Xyrauchen texanus by modifying reservoir release patterns from Navajo Dam (Holden 1999). The flow recommendations were designed to mimic the natural hydrograph or flow regime in terms of magnitude, duration and frequency of flows. Water is released from the deep hypolimnetic zone of the reservoir, which results in water temperatures that are cooler than natural, pre-dam conditions. Water temperatures in the San Juan River have been monitored and recorded at several locations as part of the SJRBRIP since 1992. -

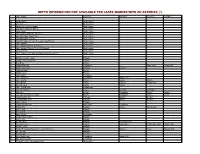

Depth Information Not Available for Lakes Marked with an Asterisk (*)

DEPTH INFORMATION NOT AVAILABLE FOR LAKES MARKED WITH AN ASTERISK (*) LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY GL Great Lakes Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes AL Baldwin County Coast Baldwin AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin AL Dog River * Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Chambers Lee Harris (GA) Troup (GA) AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson AL Highland Lake * Blount AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Lake Gantt * Covington AL Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Jordan Elmore Coosa Chilton AL Lake Martin Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa AL Lake Wedowee Clay Cleburne Randolph AL Lay Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lay Lake and Mitchell Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lewis Smith Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Lewis Smith Lake * Cullman Walker Winston AL Little Lagoon Baldwin AL Logan Martin Lake Saint Clair Talladega AL Mobile Bay Baldwin Mobile Washington AL Mud Creek * Franklin AL Ono Island Baldwin AL Open Pond * Covington AL Orange Beach East Baldwin AL Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL Pickwick Lake Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Shelby Lakes Baldwin AL Walter F. -

REMARKS by JAMES T. Mcbroom at the ANNUAL MEETING OF

UNITED STL4TES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR *******************newsrelease For Release to PM's, APRIL '7, 1962 RBMARKSBY JAMEST. McBROOM,CHIEF, DIVISION OF TECHNICALSERVICES, BUREAU OF SPORTFISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, UNITEDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, AT THE ANNUALMEETING OF THE UTAHWILDLIFE FEDERATION,SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH, APRIL 7, 1962 This is a good time for conservation. There is a bigger head of steam in the Federal Government for outdoor recreation and fish and wildlife development than I have ever seen before. There is enthusiasm. There is vigor. There is determina- tion to launch and carry out now-- not later--a program for conservation. Succeed- ing generations of Americans are promised a place to enjoy the great out-of-doors withwhich our Nation was endowed. This is splendid news for you and me, The past quarter of a century has seen usas a people concentrate tremendous energy and effort on the build-up of our .economic potential. This has been at some cost to the beauties of the countryside and the places where a man can hunt and fish. Prime scenic, recreation, and wildlife areas have fallen before the bulldozer, the cement mixer, and the dragline. Today we see messages and recommendations from the President himself on the 'importance of outdoor recreation and fish and wildlife. We see the forthcoming establishment by the President, as noted in his recent message, of a Cabinet-level advisory council on outdoor recreation. We see coming up in a few weeks a White House conference on conservation, the first in 54 years. We see a new land- acquisition policy for Federal reservoirs designed to assure adequate areas for public use. -

INTERIOR REPORTS PLANS READY for AERIAL FISH PLANTING in LAKE POWELL--May 19, 1963

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR FISH ANDWILDLIFE SERVICE Interior 5634 For Release MAY 19, 1963 INTERIORREPORTS PLANS READY FOR AERIAL FISH PLANTINGIN LAKE POWELL Tomorrow an airplane will take off from the airstrip at Page, Arizona, on a mission of interest to every fisherman in the Nation--a major step in the Depart- ment of the Interior's development of a huge recreational area in several Rocky Mountain States. The plane will be equipped with a special tank containing 500 pounds of two- inch rainbow trout and enough water to assure survival on their journey. A few minutes from Page as the plane flies, but days of hard travel on the ground, the plane will dip low over the lake being formed by the Colorado River behind newly completed Glen Canyon Dam, and the pilot will pull a lever dropping fish and water into the depths of Lake Powell. When he completes his six trips for that day, he will have placed one million fingerling trout in the new reservoir-- trout from the new Willow Beach National Fish Hatchery Arizona, downstream from Boulder City, Nevada, operated by the Fish and Wildlife Service's Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. On Wednesday, the same plane will again make six trips into the spectacularly beautiful capon of the upper Colorado to plant another million rainbows, these from the Williams Creek and Alchesay National Fish Hatcheries in eastern Arizona. Two days later, another million little trout from the Willow Beach National Fish Hatchery will take the short air trip up into the canyon to find their homes in the rapidly forming lake. -

Inventory Study Plan for Vascular Plants and Vertebrates

INVENTORY STUDY PLAN FOR VASCULAR PLANTS AND VERTEBRATES: NORTHERN COLORADO PLATEAU NETWORK NATIONAL PARK SERVICE September 30, 2000 Table of Contents Page I. Introduction and Objectives of Biological Inventory 1 II. Biophysical Overview of Northern Colorado Plateau Network 4 III. Description of Park Biological Resources and Management 7 IV. Existing Information on Vascular Plants and Vertebrates 8 V. Priorities for Additional Work 10 VI. Sampling Design Considerations and Methods 16 VII. Data Management and Voucher Specimens 29 VIII. Budget and Schedule 32 IX. Products and Deliverables 33 X. Coordination and Logistical Support 34 XI. Acknowledgements 34 XII. References Cited 35 APPENDICES A. Park descriptions (59 p.) B. Park maps (16 p.) C. Park inventory summaries (68 p.) D. Park GIS Layers (3 p.) E. Project Statements proposed for I&M funding (53 p.) F. Project summaries for unfunded inventory work or funded through other sources (30 p.) G. Park threatened, endangered and rare plant and animal lists (7 p.) H. Vegetation types for network parks (3 p.) (*print on 8 ½ x14 paper) I. Facilities and logistical support available by park (2 p.) NORTHERN COLORADO PLATEAU NETWORK STUDY PLAN I. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES OF BIOLOGICAL INVENTORY The overall mission of the National Park Service is to conserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment of this and future generations (National Park Service 1988). Actual management of national parks throughout the Service’s history has emphasized public use and enjoyment, often to the detriment of natural ecosystems within the parks (National Research Council 1992; Sellars 1997). -

April 24-Month Study Date: April 15, 2021 From

April 24-Month Study Date: April 15, 2021 From: Water Resources Group, Salt Lake City To: All Colorado River Annual Operating Plan (AOP) Recipients Current Reservoir Status March Percent April 14, April 14, Reservoir Inflow of Average Midnight Midnight (unregulated) (%) Elevation Reservoir (acre-feet) (feet) Storage (acre-feet) Fontenelle 40,460 77 6,473.21 126,000 Flaming Gorge 67,600 66 6,025.37 3,173,900 Blue Mesa 28,600 79 7,464.12 392,900 Navajo 24,500 27 6,034.00 1,049,400 Powell 296,700 45 3,564.74 8,688,600 _______________________________________________________________________ Expected Operations The operation of Lake Powell and Lake Mead in this April 2021 24-Month Study is pursuant to the December 2007 Record of Decision on Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead (Interim Guidelines), and reflects the 2021 Annual Operating Plan (AOP). Pursuant to the Interim Guidelines, the August 2020 24-Month Study projections of the January 1, 2021, system storage and reservoir water surface elevations set the operational tier for the coordinated operation of Lake Powell and Lake Mead during 2021. The August 2020 24-Month Study projected the January 1, 2021, Lake Powell elevation to be below the 2021 Equalization Elevation of 3,659 feet and above elevation 3,575 feet. Consistent with Section 6.B of the Interim Guidelines, Lake Powell is operating under the Upper Elevation Balancing Tier for water year 2021. With an 8.23 million acre-foot (maf) release from Lake Powell in water year 2021, the April 2021 24-Month Study projects the end of water year elevation at Lake Powell to be below 3,575 feet. -

2020 Green River Basin Angler Newsletter

Green River Region Angler Newsletter 2020 Fish Management The FMGR Volume 15 Crew Welcome to the 2020 issue of the Green River Robb Region Angler Newsletter. This years edition features Keith news regarding Flaming Gorge Reservoir, an update Fisheries Green River side- 2 Supervisor channel restoration from the AIS program, trout population estimates on the Green River, update on a roundtail chub project, New marina owners 3 information on the Green River side-channel project, and other insightful reads. John Lake trout - A 4-5 Walrath glance through time The Green River Fisheries Region spans from Fisheries Fontenelle drainage in the north to Flaming Gorge Biologist AIS - Conserve way 6-7 Reservoir in the south, from the Bear River in the of life west to the Little Snake in the east, and includes all the lakes, reservoirs, rivers, and streams in between. Troy Flaming Gorge 8-9 Ours is the largest fisheries region in the state and Laughlin Reservoir research one of the most diverse! From trophy lake trout to Fisheries native Colorado River cutthroat trout, smallmouth Biologist Muddy Creek native 10 bass, kokanee salmon, tiger trout and more, Green fish repatriation River has a little something for everyone. Green River trout 11-12 We manage aquatic resources for you, the people Wes population estimates of Wyoming, so your input is very important and we Gordon appreciate your comments. Please feel free to contact AIS Native fish research 13 us at 307-875-3223, or using the information Specialist provided on the last page of this newsletter. Happy Divide and Conquer 14 fishing! Regional stocking 15 Jessica Warner Evanston Historical photo 16 WGFD Mission AIS archive Specialist “Conserving Wildlife - Serving People” Fish Division Mission “As stewards of Wyoming’s aquatic resources, we are committed to conservation and enhancement of all aquatic wildlife and their habitats for future generations through scientific resource management and informed public participation. -

Cogjm.Ucrc Memor 1986-01-10.Pdf (110.1Kb)

/ UPPER COLORADO RIVER COMMISSION 355 Soi.th Fourth East Strut S(dt Lal{e City, Utah 84111 January 10, 1986 MEMORANDUM TO: Upper Colorado River Commissioners and Advisers FROM: Clint Stevens, Chief Engineer~~ SUBJECT: Content of Colorado River Storage Project Reservoirs, Streamflow, and Power Generation. On December 31, 1985 conditions at the operating Storage Units were as follows: Reservoir Change Live Storage Percent of Storage w. s. Elev. Live Content in Content Capacity Live Storage Reservoirs (feet) (1000 a.f.) (1000 a.f.) 0000 a. f.) Ca:eacity Fontenelle 6, 444.10 35.4 0.7 345 10.3% Flaming Gorge 6,023.90 3,116.8 87.1 3,749 83.1% Navajo 6,063.80 1,392.9 - 124.8 1,696 82.1% Blue Mesa 7,488.23 567.4 72.5 830 68.4% Lake Powell 3,687.19 22,993.0 110.0 25,000 92.0% TOT.!U. .28,105.5 - 175.1 31,620 88.9% Storage in Lake Mead decreased 489,000 acre-feet during the month. On December 31, 1985 the reservoir contained 23,720,000 acre-feet at water surface elevation 1,205.49 feet (82.49 feet above rated head elevation 1,123 feet.) Live storage at Lake Mead was 90.7% of the live capacity of 26,159,000 acre-feet. Storage in Fontenelle, Flaming Gorge, Navajo, Blue Mesa, and Lake Powell reservoirs decreased during the month a total of 175,100 acre-feet. January 1, 1986 Runoff Forecast Colorado River Runoff Forecast A ril-Jul Projected Inflow Percent Reservoir (acre-feet) 1961-1980 Average Fontenelle 1,100,000 127% Flaming Gorge 1,560,000 125% Blue Mesa 950,000 139% Navajo 950,000 130% Lake Powell 10,600,000 142% Streamflow Streamflow at key stations -

2019 Utah Fishing Guidebook

Utah Fishing • Utah Fishing CONTACT US CONTENTS HOW TO USE THIS GUIDEBOOK 2019 1. Review the general rules, starting on page 8. These rules explain the licenses you Turn in a poacher 3 How to use this guidebook need, the fishing methods you may use, and when you can transport and possess fish. Phone: 1-800-662-3337 4 Know the laws 2. Check general season dates, daily limits and possession limits, starting on page 19. Email: [email protected] 5 Keep your license on your Online: wildlife.utah.gov/utip phone or tablet 3. Look up a specific water in the section that starts on page 25. (If the water you’re look- ing for is not listed there, it is subject to the general rules.) Division offices 7 License and permit fees 2019 8 General rules: Licenses and Offices are open 8 a.m.–5 p.m., permits Monday • Utah Fishing through Friday. 8 Free Fishing Day WHAT’S NEW? 8 License exemptions for youth Salt Lake City Free Fishing Day: Free Fishing Day will be quagga mussels on and in boats that have 1594 W North Temple groups and organizations held on June 8, 2019. This annual event is a only been in Lake Powell for a day or two. For Box 146301 9 Discounted licenses for great opportunity to share fishing fun with a details on what’s changed at Lake Powell and Salt Lake City, UT 84114-6301 disabled veterans friend or family member. For more informa- how you can help protect your boat, please see 801-538-4700 10 Help conserve native tion, see page 8.