The Vampyre by John William Polidori: an Introduction to Lord Ruthven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

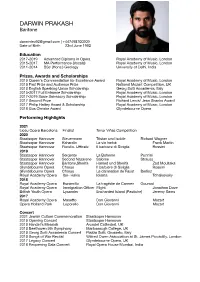

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

Revolutions in the Arts

4 Revolutions in the Arts MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES CULTURAL INTERACTION Romanticism and realism are •romanticism •impressionism Artistic and intellectual still found in novels, dramas, • realism movements both reflected and and films produced today. fueled changes in Europe during the 1800s. SETTING THE STAGE During the first half of the 1800s, artists focused on ideas of freedom, the rights of individuals, and an idealistic view of history. After the great revolutions of 1848, political focus shifted to leaders who practiced realpolitik. Similarly, intellectuals and artists expressed a “realistic” view of the world. In this view, the rich pursued their selfish interests while ordinary people struggled and suffered. Newly invented photography became both a way to detail this struggle and a tool for scientific investigation. TAKING NOTES The Romantic Movement Outlining Organize ideas and details about At the end of the 18th century, the Enlightenment idea of reason gradually gave movements in the arts. way to another major movement in art and ideas: romanticism. This movement reflected deep interest both in nature and in the thoughts and feelings of the indi- 1. The Romantic vidual. In many ways, romantic thinkers and writers reacted against the ideals of Movement the Enlightenment. They turned from reason to emotion, from society to nature. A. B. Romantics rejected the rigidly ordered world of the middle class. Nationalism II. The Shift to also fired the romantic imagination. For example, George Gordon, Lord Byron, ▼ Romantic Realism in the Arts one of the leading romantic poets of the time, fought for Greece’s freedom. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

Romantic Textualities, 22

R OMANTICT EXTUALITIES LITERATURE AND PRINT CULTURE, 1780–1840 • ISSN 1748-0116 ◆ ISSUE 22 ◆ SPRING 2017 ◆ SPECIAL ISSUE : FOUR NATIONS FICTION BY WOMEN, 1789–1830 ◆ www.romtext.org.uk ◆ CARDIFF UNIVERSITY PRESS ◆ Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840, 22 (Spring 2017) Available online at <www.romtext.org.uk/>; archive of record at <https://publications.cardiffuniversitypress.org/index.php/RomText>. Journal DOI: 10.18573/issn.1748-0116 ◆ Issue DOI: 10.18573/n.2017.10148 Romantic Textualities is an open access journal, which means that all content is available without charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author. Unless otherwise noted, the material contained in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 (cc by-nc-nd) Interna- tional License. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ for more information. Origi- nal copyright remains with the contributing author and a citation should be made when the article is quoted, used or referred to in another work. C b n d Romantic Textualities is an imprint of Cardiff University Press, an innovative open-access publisher of academic research, where ‘open-access’ means free for both readers and writers. Find out more about the press at cardiffuniversitypress.org. Editors: Anthony Mandal, Cardiff University Maximiliaan -

BYRON COURTS ANNABELLA MILBANKE, AUGUST 1813-DECEMBER 1814 Edited by Peter Cochran

BYRON COURTS ANNABELLA MILBANKE, AUGUST 1813-DECEMBER 1814 Edited by Peter Cochran If anyone doubts that some people, at least, have a programmed-in tendency to self-destruction, this correspondence should convince them. ———————— Few things are more disturbing (or funnier) than hearing someone being ironical, while pretending to themselves that they aren’t being ironical. The best or worst example is Macbeth, speaking of the witches: Infected be the air whereon they ride, And damned all those that trust them! … seeming unconscious of the fact that he trusts them, and is about to embark, encouraged by their words, on a further career of murder that will end in his death. “When I find ambiguities in your expression,” writes Annabella to Byron on August 6th 1814, “I am certain that they are created by myself, since you evidently desire at all times to be simple and perspicuous”. Annabella (born 1792) is vain, naïve, inexperienced, and “romantic”, but she’s also highly intelligent, and it’s impossible not to suspect that she knows his “ambiguities” are not “created by” herself, and that she recognizes in him someone who is the least “perspicuous” and most given to “ambiguities” who ever lived. The frequency with which both she and she quote Macbeth casually to one another (as well as, in Byron’s letters to Lady Melbourne, Richard III ) seems a subconscious way of signalling that they both know that nothing they’re about will come to good. “ … never yet was such extraordinary behaviour as her’s” is Lady Melbourne’s way of describing Annabella on April 30th 1814: I imagine she’d say the same about Byron. -

Christina Rossetti

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ChristinaRossetti MackenzieBell,HellenaTeresaMurray,JohnParkerAnderson,AgnesMilne the g1ft of Fred Newton Scott l'hl'lll'l'l'llllftlill MMM1IIIH1I Il'l'l lulling TVr-K^vr^ lit 34-3 y s ( CHRISTINA ROSSETTI J" by thtie s-ajmis atjthoe. SPRING'S IMMORTALITY: AND OTHER POEMS. Th1rd Ed1t1on, completing 1,500 copies. Cloth gilt, 3J. W. The Athen-cum.— ' Has an unquestionable charm of its own.' The Da1ly News.— 'Throughout a model of finished workmanship.' The Bookman.—' His verse leaves on us the impression that we have been in company with a poet.' CHARLES WHITEHEAD : A FORGOTTEN GENIUS. A MONOGRAPH, WITH EXTRACTS FROM WHITEHEAD'S WORKS. New Ed1t1on. With an Appreciation of Whitehead by Mr, Hall Ca1ne. Cloth, 3*. f»d. The T1mes. — * It is grange how men with a true touch of genius in them can sink out of recognition ; and this occurs very rapidly sometimes, as in the case of Charles Whitehead. Several works by this wr1ter ought not to be allowed to drop out of English literature. Mr. Mackenzie Bell's sketch may consequently be welcomed for reviving the interest in Whitehead.' The Globe.—' His monograph is carefully, neatly, and sympathetically built up.' The Pall Mall Magaz1ne.—' Mr. Mackenzie Bell's fascinating monograph.' — Mr. /. ZangwiU. PICTURES OF TRAVEL: AND OTHER POEMS. Second Thousand. Cloth, gilt top, 3*. 6d. The Queen has been graciously pleased to accept a copy of this work, and has, through her Secretary, Sir Arthur Bigge, conveyed her thanks to the Author. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Turkish Tales” – the Siege of Corinth and Parisina – Were Still to Come

1 THE CORSAIR and LARA These two poems may make a pair: Byron’s note to that effect, at the start of Lara, leaves the question to the reader. I have put them together to test the thesis. Quite apart from the discrepancy between the heroine’s hair-colour (first pointed out by E.H.Coleridge) it seems to me that the protagonists are different men, and that to see the later poem as a sequel to and political development of the earlier, is not of much use in understanding either. Lara is a man of uncontrollable violence, unlike Conrad, whose propensity towards gentlemanly self-government is one of two qualities (the other being his military incompetence) which militates against the convincing depiction of his buccaneer’s calling. Conrad, offered rescue by Gulnare, almost turns it down – and is horrified when Gulnare murders Seyd with a view to easing his escape. On the other hand, Lara, astride the fallen Otho (Lara, 723-31) would happily finish him off. Henry James has a dialogue in which it is imagined what George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda would do, once he got to the Holy Land.1 The conclusion is that he’d drink lots of tea. I’m working at an alternative ending to Götterdämmerung, in which Brunnhilde accompanies Siegfried on his Rheinfahrt, sees through Gunther and Gutrune at once, poisons Hagen, and gets bored with Siegfried, who goes off to be a forest warden while she settles down in bed with Loge, because he’s clever and amusing.2 By the same token, I think that Gulnare would become irritated with Conrad, whose passivity and lack of masculinity she’d find trying. -

Angeli, Helen Rossetti, Collector Angeli-Dennis Collection Ca.1803-1964 4 M of Textual Records

Helen (Rossetti) Angeli - Imogene Dennis Collection An inventory of the papers of the Rossetti family including Christina G. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Michael Rossetti, as well as other persons who had a literary or personal connection with the Rossetti family In The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division Prepared by : George Brandak, September 1975 Jenn Roberts, June 2001 GENEOLOGICAL cw_T__O- THE ROssFTTl FAMILY Gaetano Polidori Dr . John Charlotte Frances Eliza Gabriele Rossetti Polidori Mary Lavinia Gabriele Charles Dante Rossetti Christina G. William M . Rossetti Maria Francesca (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) Rossetti Rossetti (did not marry) (did not marry) tr Elizabeth Bissal Lucy Madox Brown - Father. - Ford Madox Brown) i Brother - Oliver Madox Brown) Olive (Agresti) Helen (Angeli) Mary Arthur O l., v o-. Imogene Dennis Edward Dennis Table of Contents Collection Description . 1 Series Descriptions . .2 William Michael Rossetti . 2 Diaries . ...5 Manuscripts . .6 Financial Records . .7 Subject Files . ..7 Letters . 9 Miscellany . .15 Printed Material . 1 6 Christina Rossetti . .2 Manuscripts . .16 Letters . 16 Financial Records . .17 Interviews . ..17 Memorabilia . .17 Printed Material . 1 7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti . 2 Manuscripts . .17 Letters . 17 Notes . 24 Subject Files . .24 Documents . 25 Printed Material . 25 Miscellany . 25 Maria Francesca Rossetti . .. 2 Manuscripts . ...25 Letters . ... 26 Documents . 26 Miscellany . .... .26 Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti . 2 Diaries . .26 Manuscripts . .26 Letters . 26 Financial Records . ..27 Memorabilia . .. 27 Miscellany . .27 Rossetti, Lucy Madox (Brown) . .2 Letters . 27 Notes . 28 Documents . 28 Rossetti, Antonio . .. 2 Letters . .. 28 Rossetti, Isabella Pietrocola (Cole) . ... 3 Letters . ... 28 Rossetti, Mary . .. 3 Letters . .. 29 Agresti, Olivia (Rossetti) . -

The Power of the Imagination~ Fall 2012 Division of Humanities—English University of Maine at Farmington

English 345 ~ English Romanticism: The Power of the Imagination~ Fall 2012 Division of Humanities—English University of Maine at Farmington Instructor: Dr. Misty Krueger Office: 216A Roberts Learning Center Office Hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10 a.m.-11 a.m. and 2:30 p.m.-3:30 p.m. Office Phone: 207-778-7473 E-mail: [email protected] (preferred method of contact) COURSE DESCRIPTION Welcome to this course, which will cover the English Romantic period (1785-1832). Notable writers from this period include Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, the Shelleys, and John Keats, among many others. In this course we will explore how their works react to important contemporary political events, reconstruct a gothic past, draw on the supernatural, and incorporate spontaneity and imagination. Our specific goal in this course is to study how the ‘powers of the imagination’ lead some of the most well-known Romantic authors to craft brilliant and inventive essays, fiction, poetry, and dramatic literature. As such, we will spend our time examining these authors’ inspirations for writing, means of composition, and conceptions of the purpose of literature, as well as its effects on the individual and society-at-large. We are about to study some of the most beautiful literature ever written in the English language. Get ready to be inspired! Get ready to become an enthusiastic, active participant in this course by contributing discussion questions about our readings, completing reading responses, giving a formal class presentation on scholarly criticism, and conversing informally with your classmates about our course materials. -

1 Byron: Six Poems of Separation

1 Byron: Six Poems of Separation edited by Peter Cochran If one’s marriage were to collapse in humiliating, semi-public circumstances, and if one were in part to blame for its collapse, one’s reaction would probably be to maintain a discreet and (one would hope) a dignified silence, and to hope that the thing might blow over in a year or so. Byron’s reaction was write, and publish, poetry about it while it was still collapsing. The first two of these poems were written in London – the first is to his wife, and the next about and to her friend and confidante Mrs Clermont – before he left England, on Thursday April 25th 1816. The next three were written in Switzerland after his departure, and are addressed to his half-sister Augusta. The last one is again to his wife. They show violent contrasts in style and tone (the Epistle to Augusta is Byron’s first poem in ottava rima), and strange, contrasting aspects of Byron’s nature. That he should wish them published at all is perhaps worrying. The urge to confess without necessarily repenting was, however, deep within him. Fare Thee Well! with its elaborate air of injured innocence, and its implication that Annabella’s reasons for leaving him remain incomprehensible, sorts ill with what we know of his behaviour during the disintegration of their marriage in the latter months of 1815. John Gibson Lockhart was moved, five years later, to protest: … why, then, did you, who are both a gentleman and a nobleman, act upon this the most delicate occasion, in all probability, your life was ever to present, as if you had been neither a nobleman nor a gentleman, but some mere overweeningly conceited poet? 1 Of A Sketch from Private Life , William Gifford, Byron’s “Literary Father”, wrote to Murray: It is a dreadful picture – Caravagio outdone in his own way. -

Illuminating the Darkness: the Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2013 Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art Cameron Dodworth University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Dodworth, Cameron, "Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel and Visual Art" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 79. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART by Cameron Dodworth A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Nineteenth-Century Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Laura M. White Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART Cameron Dodworth, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Laura White The British Gothic novel reached a level of very high popularity in the literary market of the late 1700s and the first two decades of the 1800s, but after that point in time the popularity of these types of publications dipped significantly.