Ethical Record the Proceedings of the Conway Hall Ethical Society Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

Cultural Representations of the Moors Murderers and Yorkshire Ripper Cases

CULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS OF THE MOORS MURDERERS AND YORKSHIRE RIPPER CASES by HENRIETTA PHILLIPA ANNE MALION PHILLIPS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History, and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines written, audio-visual and musical representations of real-life British serial killers Myra Hindley and Ian Brady (the ‘Moors Murderers’) and Peter Sutcliffe (the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’), from the time of their crimes to the present day, and their proliferation beyond the cases’ immediate historical-legal context. Through the theoretical construct ‘Northientalism’ I interrogate such representations’ replication and engagement of stereotypes and anxieties accruing to the figure of the white working- class ‘Northern’ subject in these cases, within a broader context of pre-existing historical trajectories and generic conventions of Northern and true crime representation. Interrogating changing perceptions of the cultural functions and meanings of murderers in late-capitalist socio-cultural history, I argue that the underlying structure of true crime is the counterbalance between the exceptional and the everyday, in service of which its second crucial structuring technique – the depiction of physical detail – operates. -

'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Cummins, ID and King, M http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1112387 Title 'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Authors Cummins, ID and King, M Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/38760/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction The Criminal Justice System is a part of society that is both familiar and hidden. It is familiar in that a large part of daily news and television drama is devoted to it (Carrabine, 2008; Jewkes, 2011). It is hidden in the sense that the majority of the population have little, if any, direct contact with the Criminal Justice System, meaning that the media may be a major force in shaping their views on crime and policing (Carrabine, 2008). As Reiner (2000) notes, the debate about the relationship between the media, policing, and crime has been a key feature of wider societal concerns about crime since the establishment of the modern police force. -

“Dead Cities, Crows, the Rain and Their Ripper, the Yorkshire Ripper”: the Red Riding Novels (1974, 1977, 1980, 1983) of David Peace As Lieux D’Horreur ______

International Journal of Criminology and Sociological Theory, Vol. 6, No.3, June 2013, 43-56 “Dead Cities, Crows, the rain and their Ripper, The Yorkshire Ripper”: The Red Riding Novels (1974, 1977, 1980, 1983) of David Peace as Lieux d’horreur ________________________________________________________________________ Martin S. King1 Ian D. Cummins2 Abstract This article explores the role and importance of place in the Red Riding novels of David Peace. Drawing on Nora’s (1989) concept of Lieux de mémoire and Rejinders’ (2010) development of this work in relation to the imaginary world of the TV detective and engaging with a body of literature on the city, it examines the way in which the bleak Yorkshire countryside and the city of Leeds in the North of England, in particular, is central to the narrative of Peace’s work and the locations described are reflective of the violence, corruption and immorality at work in the storylines. While Nora (1984) and Rejinders (2010) describe places as sites of memory negotiated through the remorse of horrific events, the authors agree that Peace’s work can be read as describing L’ieux d’horreur; a recalling of past events with the violence and horror left in. Introduction Pierre Nora’s (1989) concept of Lieux de mémoire examines the ways in which a “rapid slippage of the present into a historical past that is gone for good” (Nora, 1989:7) is compensated for by the focus of memory on particular physical spaces. Nora (1989) outlines an idea of a modern world obsessed with the past and in search of roots and identity that are fast disappearing, a loss of collectively remembered values replaced by a socially constructed version of history as a representation of the past. -

The Stabbing of George Harry Storrs

THE STABBING OF GEORGE HARRY STORRS JONATHAN GOODMAN $15.00 THE STABBING OF GEORGE HARRY STORRS BY JONATHAN GOODMAN OCTOBER OF 1910 WAS A VINTAGE MONTH FOR murder trials in England. On Saturday, the twenty-second, after a five-day trial at the Old Bailey in London, the expatriate American doctor Hawley Harvey Crippen was found guilty of poi soning his wife Cora, who was best known by her stage name of Belle Elmore. And on the following Monday, Mark Wilde entered the dock in Court Number One at Chester Castle to stand trial for the stabbing of George Harry Storrs. He was the second person to be tried for the murder—the first, Cornelius Howard, a cousin of the victim, having earlier been found not guilty. The "Gorse Hall mystery," as it became known from its mise-en-scene, the stately residence of the murdered man near the town of Stalybridge in Cheshire, was at that time almost twelve months old; and it had captured the imagination of the British public since the morning of November 2, 1909, when, according to one reporter, "the whole country was thrilled with the news of the outrage." Though Storrs, a wealthy mill-owner, had only a few weeks before erected a massive alarm bell on the roof of Gorse Hall after telling the police of an attempt on his life, it did not save him from being stabbed to death by a mysterious intruder. Storrs died of multiple wounds with out revealing anything about his attacker, though it was the impression of [Continued on back flap] THE STABBING OF GEORGE HARRY STORRS THE STABBING OF JONATHAN GOODMAN OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS Copyright © 1983 by the Ohio State University Press All rights reserved. -

University of Birmingham Foucault and True Crime

University of Birmingham Foucault and true crime Downing, Lisa DOI: 10.1017/9781316492864.014 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Downing, L 2018, Foucault and true crime. in L Downing (ed.), After Foucault : Culture, Theory and Criticism in the 21st Century. After Series, Cambridge University Press, pp. 185-200. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316492864.014 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 15/05/2019 This material has been published in After Foucault: Culture, Theory, and Criticism in the 21st Century edited by Lisa Downing https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316492864.014. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re- distribution or re-use. © Cambridge University Press 2018. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Why Are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version EARNSHAW, Antony Robert (2017). Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? Masters, Sheffield Hallam University. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

Our Side of the Mirror: the (Re)

inolo rim gy C : d O n p a e n y King, Social Crimonol 2013, 1:1 g A o c l c o i e c s DOI: 10.4172/2375-4435.1000104 s o Sociology and Criminology-Open Access S ISSN: 2375-4435 ReviewResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Our Side of the Mirror: The (Re)-Construction of 1970s’ Masculinity in David Peace’s Red Riding Martin King1* and Ian Cummins2 1Department of Social Work and Social Change, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK 2Department of Social Work-University of Salford, UK Abstract David Peace and the late Gordon Burn are two British novelists who have used a mixture of fact and fiction in their works to explore the nature of fame, celebrity and the media representations of individuals caught up in events, including investigations into notorious murders. Both Peace and Burn have analysed the case of Peter Sutcliffe, who was found guilty in 1981 of the brutal murders of thirteen women in the North of England. Peace’s novels filmed as the Red Riding Trilogy are an excoriating portrayal of the failings of misogynist and corrupt police officers, which allowed Sutcliffe to escape arrest. Burn’s somebody’s Husband Somebody’ Son is a detailed factual portrait of the community where Sutcliffe spent his life. Peace’s technique combines reportage, stream of consciousness and changing points of views including the police and the victims to produce an episodic non linear narrative. The result has been termed Yorkshire noir. The overall effect is to render the paranoia and fear these crimes created against a backdrop of the late 1970s and early 1980s. -

Bigmouth Strikes Again As Morrissey's Book Hits the Shelves

40 FGM FridayOctober 18 2013 | the times the times | FridayOctober 18 2013 FGM 41 arts FRONT COVER: MICK HUTSON/GETTY IMAGES BELOW: STEPHEN WRIGHT /SMITHSPHOTOS.COM arts Bigmouth strikes Morrissey wasagenius,but he’s still singingthe same song,sayslifelong fan Robert Crampton fIhad to rank the most seminal we know that he can hold agrudge, moments of my youth, the Jam and my goodness, he can. again as Morrissey’s splitting up in 1982 would be He has apop at SteveHarley and one, the Clash falling to bits in Noddy Holder.And morethan apop 1983 would be another,and the —itgets tedious —atthe judge who Smiths calling it aday in 1987 presided over the courtcase (that he would be athird. Looking back, lost) when the Smiths’bassist and bookhitsthe shelves Iof the three ruptures, the last drummer wanted abigger shareof wasbyfar the most significant. the band’sroyalties. The appeal Morrissey and Marr still had plenty courtjudges get akicking too. of creativeenergy left in the tank, As do John Peel, Rough Trade, paragraphaiming foraT.S.Eliot-style same time beingaware of his own yetastheir respectivesolo careers SpandauBallet.Pretty It’s self-absorbed, evocation of Mancunian squalor. preposterousness. “Naturally my birth suggest,they needed eachother to much everyone. “Pastplacesofdread, we walk in the almostkills my mother,for my head is alchemise that energy.Soalot of The Smiths split up overlongand center [sic] of the road,” Morrissey toobig,” he announces. He finds the great songs never got written. morethan aquarter of writes,possibly by quill, on the city firstofmanyopportunitiestobea Iwas 18 when Ifirst heardthe acenturyago.Inthe essentialreading. -

Tameside Bibliography

TAMESIDE BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by the staff of: Tameside Local Studies & Archives Centre, Central Library, Old Street, ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE, Lancashire, OL6 7SG. 1992 (amended 1996/7 & 2006) NOTES 1) Most of the items in the following bibliography are available for reference in the Local Studies & Archives Centre, Ashton-Under-Lyne. 2) It should not be assumed that, because a topic is not covered in the bibliography, nothing exists on it. If you have a query for which no material is listed, please contact the Local Studies Library. 3) The bibliography will be updated periodically. ABBREVIATIONS GMAU Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit THSLC Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire TLCAS Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society TAMS Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society CONTENTS SECTION DESCRIPTION PAGE Click on section title to jump to page BIBLIOGRAPHIES 6 GENERAL HISTORIES 8 AGRICULTURE 10 ANTI-CORN LAW LEAGUE 11 ARCHAEOLOGY see: PREHISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY 70 ARCHITECTURE 12 ART AND ARTISTS 14 AUTOBIOGRAPHIES 15 AVIATION 20 BIOGRAPHIES 21 BLACK AND ASIAN HISTORY 22 BLANKETEERS 23 CANALS 24 CHARTISM 25 CIVIL WAR 28 COTTON FAMINE 29 COTTON INDUSTRY see: INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 39 CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS 31 DARK AGES - MEDIEVAL SETTLEMENT - THE TUDORS 33 EDUCATION 35 GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY 37 HATTING 38 INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF COTTON 39 LAW AND ORDER 45 LEISURE 48 CONTENTS (continued) SECTION DESCRIPTION PAGE Click on section title to jump to page LOCAL INDUSTRIES (excluding -

Daily Express

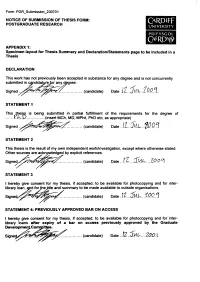

Form: PGR_Submission_200701 NOTICE OF SUBMISSION OF THESIS FORM: POSTGRADUATE RESEARCH Ca r d if f UNIVERSITY PRIFYSGOL CAERDVg) APPENDIX 1: Specimen layout for Thesis Summary and Declaration/Statements page to be included in a Thesis DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in capdidatyrefor any degree. S i g n e d ................. (candidate) Date . i.L.. 'IP .Q . STATEMENT 1 This Thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Y .l \.D ..................(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed (candidate) Date .. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Sig (candidate) Date STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, apd for thefitle and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signe4x^^~^^^^pS^^ ....................(candidate) Date . STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Graduate Developme^Committee. (candidate) Date 3ml-....7.00.1 EXPRESSIONS OF BLAME: NARRATIVES OF BATTERED WOMEN WHO KILL IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY DAILY EXPRESS i UMI Number: U584367 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

A Practice-As-Research Phd Volume 1

An Investigation into How Engagement with the Context and Processes of Collaborative Devising Affects the Praxis of the Playwright: A Practice-as-Research PhD Volume 1 Karen Morash Submitted for the Degree of PhD October 2016 Goldsmiths, University of London Department of Theatre and Performance 2 This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signed, Karen Morash 3 Abstract An Investigation into How Engagement with the Context and Processes of Collaborative Devising Affects the Praxis of the Playwright: A Practice-as-Research PhD The central research inquiry of this dissertation is how the experience of working within a collaborative context, employing the processes of devising, affects a playwright. It springs from the presentiment that the processes of devising are significantly different than traditional playwriting methodologies and have the potential to offer short and long-term benefits to both playwright and collaborators. A central focus of the dissertation is the figure of the writer-deviser as a distinctive artist with a particular skillset developed from both devising praxis and standard playwright training (which traditionally does not emphasise collaborative theatre-making). This dissertation therefore examines the historical and contemporary context of the writer-deviser in order to provide a foundation for the presentation and exegesis of my practice-as-research: a play written via the devising process and another play written as a solo playwright.