Boyhood Days in the Owens Valley 1890-1908

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instructionally Related Activities Report

Instructionally Related Activities Report Linda O’Hirok, ESRM ESRM 463 Water Resources Management Owens Valley Field Trip, March 4-6, 2016 th And 5 Annual Water Symposium, April 25, 2016 DESCRIPTION OF THE ACTIVITY; The students in ESRM 463 Water Resources Management participated in a three-day field trip (March 4-6, 2016) to the Owens Valley to explore the environmental and social impacts of the City of Los Angeles (LA DWP) extraction and transportation of water via the LA Aqueduct to that city. The trip included visiting Owens Lake, the Owens Valley Visitor Center, Lower Owens Restoration Project (LORP), LA DWP Owens River Diversion, Alabama Gates, Southern California Edison Rush Creek Power Plant, Mono Lake and Visitor Center, June Mountain, Rush Creek Restoration, and the Bishop Paiute Reservation Restoration Ponds and Visitor Center. In preparation for the field trip, students received lectures, read their textbook, and watched the film Cadillac Desert about the history of the City of Los Angeles, its explosive population growth in the late 1800’s, and need to secure reliable sources of water. The class also received a summary of the history of water exploitation in the Owens Valley and Field Guide. For example, in 1900, William Mulholland, Chief Engineer for the City of Los Angeles, identified the Owens River, which drains the Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains, as a reliable source of water to support Los Angeles’ growing population. To secure the water rights, Los Angeles secretly purchased much of the land in the Owens Valley. In 1913, the City of Los Angeles completed the construction of the 223 mile, gravity-flow, Los Angeles Aqueduct that delivered Owens River water to Los Angeles. -

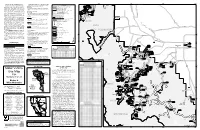

Cottonwood Lakes / New Army Pass Trail

Inyo National Forest Cottonwood Lakes / New Army Pass Trail Named for the cottonwood trees which were located at the original trailhead in the Owens Valley, the Cottonwood Lakes are home to California's state fish, the Golden Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita). The lakes are located in an alpine basin at the southern end of the John Muir Wilder- ness. They are surrounded by high peaks of the Sierra Nevada, including Cirque Peak and Mt. Lang- ley. The New Army Pass Trail provides access to Sequoia National Park and the Pacific Crest Trail. Trailhead Facilities: Water: Yes Bear Resistant Food Storage Lockers: Yes Campgrounds: Cottonwood Lakes Trailhead Campground is located at the trailhead. Visitors with stock may use Horseshoe Meadow Equestrian Camp, located nearby. On The Trail: Food Storage: Food, trash and scented items must be stored in bear-resistant containers. Camping: Use existing campsites. Camping is prohibited within 25 feet of the trail, and within 100 feet of water. Human Waste: Bury human waste 6”-8” deep in soil, at least 100 feet from campsites, trails, and water. Access: Campfires: Campfires are prohibited above 10,400 ft. The trailhead is located approximately 24 miles southwest of Lone Pine, CA. From Highway Pets: Pets must be under control at all times. 395 in Lone Pine, turn west onto Whitney Portal Additional Regulations: Information about Kings Road. Drive 3.5 miles and turn south (left) onto Canyon National Park regulations is available at Horseshoe Meadow Road. Travel approximately www.nps.gov/seki, www.fs.usda.gov/goto/inyo/ 20 miles, turn right and follow signs to the cottonwoodlakestrail or at Inyo National Forest Cottonwood LAKES Trailhead. -

Eocene Origin of Owens Valley, California

geosciences Article Eocene Origin of Owens Valley, California Francis J. Sousa College of Earth, Oceans, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA; [email protected] Received: 22 March 2019; Accepted: 26 April 2019; Published: 28 April 2019 Abstract: Bedrock (U-Th)/He data reveal an Eocene exhumation difference greater than four kilometers athwart Owens Valley, California near the Alabama Hills. This difference is localized at the eastern fault-bound edge of the valley between the Owens Valley Fault and the Inyo-White Mountains Fault. Time-temperature modeling of published data reveal a major phase of tectonic activity from 55 to 50 Ma that was of a magnitude equivalent to the total modern bedrock relief of Owens Valley. Exhumation was likely accommodated by one or both of the Owens Valley and Inyo-White Mountains faults, requiring an Eocene structural origin of Owens Valley 30 to 40 million years earlier than previously estimated. This analysis highlights the importance of constraining the initial and boundary conditions of geologic models and exemplifies that this task becomes increasingly difficult deeper in geologic time. Keywords: low-temperature thermochronology; western US tectonics; quantitative thermochronologic modeling 1. Introduction The accuracy of initial and boundary conditions is critical to the development of realistic models of geologic systems. These conditions are often controlled by pre-existing features such as geologic structures and elements of topographic relief. Features can develop under one tectono-climatic regime and persist on geologic time scales, often controlling later geologic evolution by imposing initial and boundary conditions through mechanisms such as the structural reactivation of faults and geomorphic inheritance of landscapes (e.g., [1,2]). -

Reditabs Viagra

Bishop Paiute Tribal Council Update The Bishop Indian Tribal Council wishes all of the community a Happy New Year 2018. In reflection of last years efforts to improve the livelihood of our Tribal Members through the growth of Tribal services, we anticipate a successful 2018 ahead. Contin- ue to stay updated with the good things happening in our community by continuing to read our monthly newsletter articles and attend tribal meetings. A new way to com- municate concerns and give feedback on programs directly to the Tribal Council will be to attend our new Monthly CIM (Community Input Meetings), starting with the first one on January 16, 2018 @ 6pm in the Tribal Chambers. Our monthly CIM’s will be an open discussion with the BITC talking about current efforts and concerns the commu- nity may have. As always, If you have any suggestions or comments to assist us in these efforts, please contact Brian Poncho @ 760-873-3584 Ext.1220. Law Enforcement - The Tribal Police Department has began efforts to identify Non-Indians in our community who are participating in drug activity on the Reservation. Once identified the Council will begin efforts of removal off of Tribal Lands. These efforts have been a result of continuous concerns from our tribal community. If you have any concerns about persons Tribal/Non-Tribal on the reservation who may be involved in drug activi- ty please contact our Tribal Police Department. Tribal Police Chief Hernandez can be contacted @ (760) 920-2759 New Gas Station- Plans for a new gas station on the corner of See Vee Ln and Line St have been developed throughout the year 2016-2017 and will begin by Spring 2018. -

Yosemite, Lake Tahoe & the Eastern Sierra

Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe PCC EXTENSION YOSEMITE, LAKE TAHOE & THE EASTERN SIERRA FEATURING THE ALABAMA HILLS - MAMMOTH LAKES - MONO LAKE - TIOGA PASS - TUOLUMNE MEADOWS - YOSEMITE VALLEY AUGUST 8-12, 2021 ~ 5 DAY TOUR TOUR HIGHLIGHTS w Travel the length of geologic-rich Highway 395 in the shadow of the Sierra Nevada with sightseeing to include the Alabama Hills, the June Lake Loop, and the Museum of Lone Pine Film History w Visit the Mono Lake Visitors Center and Alabama Hills Mono Lake enjoy an included picnic and time to admire the tufa towers on the shores of Mono Lake w Stay two nights in South Lake Tahoe in an upscale, all- suites hotel within walking distance of the casino hotels, with sightseeing to include a driving tour around the north side of Lake Tahoe and a narrated lunch cruise on Lake Tahoe to the spectacular Emerald Bay w Travel over Tioga Pass and into Yosemite Yosemite Valley Tuolumne Meadows National Park with sightseeing to include Tuolumne Meadows, Tenaya Lake, Olmstead ITINERARY Point and sights in the Yosemite Valley including El Capitan, Half Dome and Embark on a unique adventure to discover the majesty of the Sierra Nevada. Born of fire and ice, the Yosemite Village granite peaks, valleys and lakes of the High Sierra have been sculpted by glaciers, wind and weather into some of nature’s most glorious works. From the eroded rocks of the Alabama Hills, to the glacier-formed w Enjoy an overnight stay at a Yosemite-area June Lake Loop, to the incredible beauty of Lake Tahoe and Yosemite National Park, this tour features lodge with a private balcony overlooking the Mother Nature at her best. -

Motor Vehicle Use

350000 360000 370000 380000 118°45'0"W 30E301A 118°37'30"W Continued on Casa Diablo Map 118°30'0"W 118°22'30"W T OPERATOR RESPONSIBILITIES EXPLANATION OF LEGEND ITEMS 04S15B o PINE GROVE 04S15 M Legend PICNIC AREA 3 04S15E a 0 Operating a motor vehicle on National Forest System Roads Open to Highway Legal Vehicles Only: m " LOWER E m Roads Open to Highway Legal Vehicles 5" 3 roads, National Forest System trails, and in areas on 04S15C 9 & 0 o 1 UPPER t PINE h National Forest System lands carries a greater These roads are open only to motor vehicles licensed under Roads Open to All Vehicles 04S18 " 2 9 0 GROVE 3 responsibility than operating that vehicle in a city or other State law for general operation on all public roads within the 04S18B E Trails Open to All Vehicles CAMPGROUND 0 developed setting. Not only must you know and follow all State. 3 applicable traffic laws, you need to show concern for the Trails Open to Vehicles 50" or Less in Width 04S12O 04S18A environment as well as other forest users. The misuse of Roads Open to All Vehicles: ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Trails Open to Motorcycles Only 06S08 0 6 motor vehicles can lead to the temporary or permanent S 06S08A G Rock 0 04S12P o Seasonal Designation 6 r closure of any designated road, trail, or area. As a motor These roads are open to all motor vehicles, including smaller 9" Creek g (See Seasonal Designation Table) e 04S12Q vehicle operator, you are also subject to State traffic law, off-highway vehicles that may not be licensed for highway Lake R d including State requirements for licensing, registration, and use (but not to oversize or overweight vehicles under State Highways, US, State 9" 06S06A MOSQUITO FLAT operation of the vehicle in question. -

The History of Valentine Camp by Mary Farrell

History of Valentine Camp Mary M. Farrell Trans-Sierran Archaeological Research P.O. Box 840 Lone Pine, CA 93545 November 7, 2015 Prepared for Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserve University of California, Santa Barbara, Natural Reserve System Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory 1016 Mt. Morrison Road Mammoth Lakes, CA 93546 Abstract Located in Mammoth Lakes, California, Valentine Camp and the nearby Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory form the Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserve, a field research station in the University of California's Natural Reserve System. The University’s tenure at Valentine Camp began over 40 years ago, but the area’s history goes back thousands of years. Before the arrival of Euroamericans in the nineteenth century, the region was home to Paiutes and other Native American tribes. Land just east of Valentine Camp was surveyed under contract with the United States government in 1856, and mineral deposits in the mountains just west of Valentine Camp brought hundreds of miners to the vicinity in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Even as mining in the region waned, grazing increased. The land that became Valentine Camp was patented in 1897 by Thomas Williams, a rancher and capitalist who lived in Owens Valley. It was Williams’s son, also Thomas, who sold the 160 acres to Valentine Camp’s founders. Those founders were very wealthy, very influential men in southern California who could have, and did, vacation wherever they wanted. Anyone familiar with the natural beauty of Mammoth Lakes would not be surprised that they chose to spend time at Valentine Camp. Valentine Camp was donated to the University of California Natural Land and Water Reserve System (now the Natural Reserve System) in 1972 to ensure the land’s continued protection. -

Yosemite National Park Foundation Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Yosemite National Park California Contact Information For more information about Yosemite National Park, Call (209) 372-0200 (then dial 3 then 5) or write to: Public Information Office, P.O. Box 577, Yosemite, CA 95389 Park Description Through a rich history of conservation, the spectacular The geology of the Yosemite area is characterized by granitic natural and cultural features of Yosemite National Park rocks and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years have been protected over time. The conservation ethics and ago, the Sierra Nevada was uplifted and then tilted to form its policies rooted at Yosemite National Park were central to the relatively gentle western slopes and the more dramatic eastern development of the national park idea. First, Galen Clark and slopes. The uplift increased the steepness of stream and river others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, beds, resulting in formation of deep, narrow canyons. About ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln’s signing 1 million years ago, snow and ice accumulated, forming glaciers the Yosemite Grant in 1864. The Yosemite Grant granted the at the high elevations that moved down the river valleys. Ice Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the State thickness in Yosemite Valley may have reached 4,000 feet during of California stipulating that these lands “be held for public the early glacial episode. The downslope movement of the ice use, resort, and recreation… inalienable for all time.” Later, masses cut and sculpted the U-shaped valley that attracts so John Muir led a successful movement to establish a larger many visitors to its scenic vistas today. -

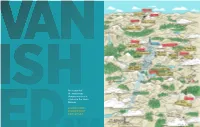

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

Mountain Whitefish Chances for Survival: Better 4 Prosopium Williamsoni

Mountain Whitefish chances for survival: better 4 Prosopium williamsoni ountain whitefish are silvery in color and coarse-scaled with a large and the mackenzie and hudson bay drainages in the arctic. to sustain whatever harvest exists today. mountain whitefish in California and Nevada, they are present in the truckee, should be managed as a native salmonid that is still persisting 1 2 3 4 5 WHITEFISH adipose fin, a small mouth on the underside of the head, a short Carson, and Walker river drainages on the east side of in some numbers. they also are a good indicator of the dorsal fin, and a slender, cylindrical body. they are found the sierra Nevada, but are absent from susan river and “health” of the Carson, Walker, and truckee rivers, as well as eagle lake. lake tahoe and other lakes where they still exist. Whitefish m Mountain Whitefish Distribution throughout western North america. While mountain whitefish are regarded aBundanCe: mountain whitefish are still common in populations in sierra Nevada rivers and tributaries have California, but they are now divided into isolated popula- been fragmented by dams and reservoirs, and are generally as a single species throughout their wide range, a thorough genetic analysis tions. they were once harvested in large numbers by Native scarce in reservoirs. a severe decline in the abundance of americans and commercially harvested in lake tahoe. mountain whitefish in sagehen and prosser Creeks followed would probably reveal distinct population segments. the lahontan population there are still mountain whitefish in lake tahoe, but they the construction of dams on each creek. -

Owens Valley Groundwater Basin Bulletin 118

South Lahontan Hydrologic Region California’s Groundwater Owens Valley Groundwater Basin Bulletin 118 Owens Valley Groundwater Basin • Groundwater Basin Number: 6-12 • County: Inyo & Mono • Surface Area: 661,000 acres (1,030 square miles) Basin Boundaries and Hydrology This groundwater basin underlies Benton, Hammil, and Chalfant Valleys in Mono County and Round and Owens Valleys in Inyo County. This basin is bounded by nonwater-bearing rocks of the Benton Range on the north, of the Coso Range on the south, of the Sierra Nevada on the west, and of the White and Inyo Mountians on the east (Jennings 1958; DWR 1964; Matthews and Burnett 1965; Strand 1967; Danskin 1998) This system of valleys is drained by several creeks to the Owens River, which flows southward into the Owens (dry) Lake, a closed drainage depression in the southern part of the Owens Valley. Average annual precipitation is 30 inches in the Sierra Nevada, 7 to 10 inches in the White and Inyo Mountains, and 4 to 6 inches on the Owens Valley floor (Groeneveld and others 1986a; 1986b; Duell 1990; Hollett and others 1991). Hydrogeologic Information Water Bearing Formations The water-bearing materials of this basin are sediments that fill the valley and reach at least 1,200 feet thick (DWR 1964). The primary productive unit is Quaternary in age and is separated into upper, lower and middle members (Danskin 1998). Upper Member. The upper member is composed of unconsolidated coarse alluvial fan material deposited along the margin of the basin, grading into layers of sand and silty clay of fluvial and lacustrine origin toward the axis of the basin. -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTI8 SMITH, DIEECTOE WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 296 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF CALIFORNIA PART II. SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASIN PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OP JOHN C. HOYT BY B. D. WOOD In cooperation with the State Water Commission and the Conservation Commission of the State of California WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 NOTE. A complete list of the gaging stations maintained in the San Joaquin River basin from 1888 to July 1, 1912, is presented on pages 100-102. 2 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS IN SAN JOAQUIN RIYER BASIN, CALIFORNIA. By B. D. WOOD. INTRODUCTION. This gazetteer is the second of a series of reports on the* surf ace waters of California prepared by the United States Geological Survey under cooperative agreement with the State of California as repre sented by the State Conservation Commission, George C. Pardee, chairman; Francis Cuttle; and J. P. Baumgartner, and by the State Water Commission, Hiram W. Johnson, governor; Charles D. Marx, chairman; S. C. Graham; Harold T. Powers; and W. F. McClure. Louis R. Glavis is secretary of both commissions. The reports are to be published as Water-Supply Papers 295 to 300 and will bear the fol lowing titles: 295. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part I, Sacramento River basin. 296. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part II, San Joaquin River basin. 297. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part III, Great Basin and Pacific coast streams. 298. Water resources of California, Part I, Stream measurements in the Sacramento River basin.